Caroline Wogan Durieux | |

|---|---|

| Born | Caroline Spelman Wogan January 22, 1896 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | November 26, 1989 Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | National Autonomous University of Mexico |

| Alma mater | H. Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts |

| Occupation(s) | artist, professor |

| Years active | 1900–1989 |

| Known for | printmaking, painting, teaching |

| Spouse | Pierre Durieux (m. 1920–1949; death) |

| Awards | Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award (1980) |

Caroline Wogan Durieux (January 22, 1896 – November 26, 1989) was an American printmaker, painter, and educator. She was a Professor Emeritus at both Louisiana State University, where she worked from 1943 to 1964 and at Newcomb College of Tulane University (1937–1942). Carl Zigrosser, Keeper of Prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, wrote:

"Durieux is master of her instrument. It is like an epigram delivered in a deadpan manner:the meaning sinks in casually; when all of a sudden the full impact dawns on one, it haunts one for days. Her work has that haunting quality because its roots are deep, its vision profound".

Early life and education

She was born Caroline Spelman Wogan in New Orleans, Louisiana, on January 22, 1896; into a Creole family.[1] At the age of 4, she began drawing and received art lessons from Mary Williams Butler (1873–1937), she was a local artist and a member of the faculty of art at Newcomb College at Tulane University.[2] She worked in watercolor from the age of six and in 1908 at the age of 12 created a portfolio of ten watercolors depicting New Orleans scenery. One of those watercolors, Church Pews is illustrated below. Most of these early works are now in The Historic New Orleans Collection.[3] She continued at Newcomb College of Tulane University in the Art School headed by Ellsworth Woodward. From her college days, she was interested in satire and the use of humor in her imagery. Durieux earned a Bachelor's in Design in 1916 and a Bachelor's in Art Education in 1917, and she pursued graduate studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts led by Henry Bainbridge McCarter.[4]

She returned to Louisiana after graduate school and in April 1920 married Pierre Van Grundard Durieux (1889–1949). Pierre worked in his family's business importing laces and dress goods from many Latin American countries.[5]

Quotations

"my grandmother gave me a slate and pencils. I drew constantly despite the occasional taunts of the other children. I remember one cousin complaining about one of my drawings of a blue horse, to which I retorted: "I can draw the horse blue if I want, because it is my horse." I was only really happy as a child when I was drawing".

"Every Saturday morning I had class taught by Mary Butler, a friend of my mother's who taught at Newcomb. She was very good because she just helped you. She didn't impose anything on you. She taught me perspective—to see things I hadn't seen before. She taught me the rules. At first the rules bothered me a lot until I decided I didn't have to make each thing exact. I had good visual memory. I could also draw people and it looked like them in a very crude sort of way. I used to get likenesses which amused me to no end—I loved that."

"Mr. Woodward would often give us a subject to depict in some manner. One day he gave as a subject: "To him who hath, more shall be given." I made a black and white line drawing. It showed a man in a hospital background surrounded by five children being presented with a new set of twins by a nurse. It brought down the house because it was the only one that was funny. All the other students had chosen to work more solemnly. Woodward couldn't take this seriously; he would have if he could have; he just couldn't. He gave us another one dealing with death. I got criticized because skeletons are supposed to be very sad, and I had drawn a happy one"

Career

Pierre's work led to a job in Cuba which Caroline described as a time of "quiet artistic growth that heightened her sense of color." Caroline Durieux lived in the French Quarter in the mid-1920s, and was part of a circle of talented and creative individuals featured in a private publication, "Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles." Her next-door neighbors included author, William Faulkner, and silver designer, William Spratling.

Spirituality and religion

Durieux was born into a mixed-religious marriage at a time when that was taken more seriously than it is today. The Wogan family was Roman Catholic; the Spelmans were Episcopalian. Caroline often referred to her father, Nicholas, as if he were officially excommunicated from the Catholic Church because of his marriage to her mother.[6]

On Sundays Caroline would be taken to protestant services with her mother only to be whisked off to the "bells and smells" of the Catholic Cathedral's High Mass.[6]

Religion is the central theme in Benediction, Priests,Acolytes,Church Interior, Death Masker, First Communion (2),Idle Angels, Insomne, Lot's Wife, Lady Godiva, Annunciation, On the Levee, Easter Egg, Iron Sharpeneth Iron, A Cult Leader Exhorts His Flock, Mother Carre and others.

Artist statement

"I cannot remember a time when I did not have a pencil in hand trying to put down on a slate, on wrapping paper or even on the woodwork visual ideas concerning my environment

To me art is not work. It is fun.

If I happen to give a measure of enjoyment to others as I entertain myself, so much the better. If not, well ... that's just too bad!"[7]

Durieux in Cuba

On April 19, 1920, she married childhood friend Pierre Durieux at her parents' home at 1226 Louisiana Avenue in New Orleans. In October 1920, the Durieux's moved to Havana, Cuba where Pierre took a position with General Motors.[7]

In late December 1920, Caroline Durieux returned to New Orleans to give birth to the couple's first and only child. She spends the next six months recuperating from postpartum complications at her parents' vacation home in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. When she returned to Cuba she and Pierre lived in the downtime neighborhood of Vedado. She worked briefly in a design firm but spent most of her time creating paintings, drawings and watercolors of her colorful surroundings. She has said color, and most of her work from this period were still lifes, flowers and landscapes.

At the request of her housekeeper, she became involved with the native women in the community, helping them devise a rudimentary method of birth control.[7]

Diego Rivera and New Orleans

This essay by Marysol Nieves appeared in a 1999 Christie's publication highlighting the provenance of a Rivera painting, La bordadora (The Embroiderer). "The 1920s ushered in a period of extraordinary and radical cultural transformation in Mexico. Perhaps nowhere was this reinvention more notable than in the visual arts, where artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, advocated a new approach to artmaking that was socially and politically engaged while grounded in notions of accessibility and civic engagement.

Their model galvanized artists in the United States who also sought to break free from the dominance of European art to make art that was rooted in modernism but reflected their own specific reality. The cross-cultural dialogue that ensued saw many American artists travel to Mexico, while the leading Mexican muralist spent extended periods of time in the United States, executing murals, paintings, and prints; participating in exhibitions; and teaching and interacting with local artists. Louisiana (and particularly New Orleans) artists, writers and intellectuals flocked to Mexico….drawn to the formal affinities between pre-Columbian art and modernism as well as the socially and politically charged works of their fellow artists across the border. For example, New Orleans natives William Spratling and Caroline Durieux befriended, studied and collaborated on numerous occasions with artists like Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Emilio Amero and Carlos Orozco Romero.

Along with Tulane University, the then burgeoning New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club also served as an important nexus between these two thriving artists communities. In 1928, the Times-Picayune declared Diego Rivera "the greatest painter on the North American continent".[8] while announcing a four-day exhibition of his oil paintings and watercolors at the New Orleans Arts and Craft Club. Other related exhibitions followed including a 1933 exhibition of works by Mexican artists (Rivera, Amero and Tamayo) alongside works by Spratling and Durieux.

Spratling, an accomplished silver designer, traveled to Mexico in the late 1920s with Tulane University archeologist Frans Blom. The news of Blom's excavations of Mayan ruins and his explorations of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (also a source of study for Rivera) published in local newspapers and magazines captivated Louisianans.[9] Motivated by these accounts, Spratling traveled with Blom in the late 1920s to study ancient indigenous art and archeology. The trip ultimately prompted Spratling's move to Taxco, Mexico where he played a significant role in promoting Mexican silversmithing traditions.

The painter and printmaker Caroline Wogan Durieux arrived in Mexico City in 1926 with her husband Pierre, the newly appointed Latin American corporate representative of General Motors. Armed with a letter of introduction from Blom to the great muralist Diego Rivera, Durieux quickly absorbed her new milieu. Durieux not only befriended many of Mexico's leading artists and intellectuals of the day (including Rivera and Kahlo) but flourished under the tutelage of Rivera and Emilio Amero with whom she honed her skills as a painter and printmaker as well as the satirical qualities of her work. In 1929, curator René d'Harnoncourt, organized a solo exhibition of Caroline's oil paintings and drawings at the Sonora News Company in Mexico City."[10]

Rivera published an enthusiastic review in the journal Mexican Folkways:

"Since she has lived among us, she has developed a close spiritual rapport with the country and simultaneously there has grown in her a painter's mature power of expression. Not only does her painting show the love of nature, exalting the grandeur of the mountains, the beauty of the peasants, and the orderly freedom of our architecture, but she has also seen our mongrel, perverted and deformed bourgeoisie, with the clear eye of a Mexican mountaineer, and yet with all the urbanity, the culture, and the occidental sophistication which are Caroline's".[11]

Durieux and Rivera's enduring friendship is perhaps best celebrated in the elegant portrait the Mexican artist painted of his New Orleans comrade in 1929 and which today hangs in the collection of the LSU Museum of Art in Baton Rouge.

Mexico City

In 1926, her husband Pierre was named chief representative of General Motors for all of Latin America, but Caroline stayed and worked in Mexico City. She received a letter of introduction to Diego Rivera from Tulane anthropologist, Franz Blom, which helped ease her transition into the local artist community. In 1929, curator Rene d'Harnoncourt, organized a solo exhibition of Caroline's oil paintings and drawings at the Sonora News Company. Rivera wrote a favorable review of his friend's exhibition, and then chose the occasion to paint her portrait. Again, a promotion for Pierre marked an important development in his wife's career. This time they moved to New York City, where Caroline forged a lifelong friendship with art dealer, Carl Zigrosser. Zigrosser championed Durieux's career, first as director of the Weyhe Gallery, then as the curator of prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and including her in his many books. It was Zigrosser who recognized Durieux's talent and eye for satire and encouraged her adoption of lithography as a primary means of artistic expression.

In 1931, the Durieuxs again were transferred to Mexico City. Eager to learn more about lithography, Durieux enrolled in the Academy of San Carlos (now known as National Autonomous University of Mexico) to study with Emilio Amero. In 1934, Durieux experimented with etching, a technique she learned from Howard Cook. Caroline wrote to Carl Zigrosser: "All my etchings are harrowing. I think it is because the medium is such a precarious one-the least slip and all is lost. I can't be funny on a copper plate. I feel tragic the moment I think of doing an etching."[12]

Back to New Orleans

In 1937, Pierre Durieux was diagnosed with severe cardiac disease. His doctors ordered him to return to the United States, so the couple left Mexico reluctantly and returned to New Orleans. Later that year, Durieux was hired to teach in Newcomb College's art department for the fall term, where she focussed on ensuring that her students could draw before advancing to other classes. In October 1937, Durieux exhibited her etching, Hunger, as a member of the Society of American Etchers (now known as the Society of American Graphic Artists). The exhibition, hosted at the Marcel Guiot Gallery, featured 50 members and artist. Durieux took on a second job as director of the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration in February 1939. In a state where racial segregation remained legal until the 1960s, Caroline's Louisiana division of the FAP was the only project not to practice discrimination. Caroline always expressed great pride in that accomplishment: "I had a feeling that an artist is an artist and it doesn't make any difference what color he or she is." Robert Armstrong Andrews, associate director of the national office, praised Durieux's work: "It is my observation that the people in Louisiana have more concern with the potentialities of the Negro and less for his limitations than the people of any other state."[13]

From 1943 to 1964, she taught in the art department at Louisiana State University.[14]

In the 1950s, Durieux experimented in printmaking; working on perfecting her electron printmaking technique (with radioactive ink) and she produced the first color cliché verre prints.[15]

In 1976, Caroline Durieux was the first living artist to be honored with a retrospective of her work at The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In 1980, she was awarded the Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award.[16]

Foreign Ateliers

In the early fifties, Caroline took a sabbatical leave to study color lithography in Paris. Her decision to seek further study is indicative of Durieux's continuing dedication to the art of printmaking and to a long life of constant learning. During her leave, she traveled throughout Europe to France, Italy, Spain and England. She eventually went to study at the studio of Edmund Desjobert (d. 1964) and Son in Paris.[17]

At first Durieux had difficulty at the workshop because of her gender:

"When I walked in to begin my work, I was given the smallest, oldest stones they could find. At first I was furious, but I used them to make my first images and brought them back in. The master printer seemed to be surprised at my ability—and I was immediately given the best, heaviest limestone they had for my next pieces."

— Caroline W. Durieux

Not only did the director of the workshop notice Durieux's talent but also they were impressed with her ability to speak their language: "Since I speak French they taught me all kinds of little tricks that they wouldn't tell the other Americans in the group because they didn't like them since they didn't speak French."[17]

She studied with Desjobert for three months in 1952 and again in 1957.

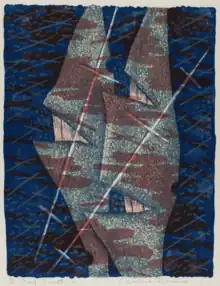

In this new medium of color lithography her work became increasingly abstract, and her satire more subtle and complex . Durieux's color lithographs are more thought-provoking and less whimsical. She said of her work at this time: "I wanted to be more emphatic, more essential. I gradually realized that what you LEAVE OUT is important."[17]

Durieux's interest in death is evident in the sober and minimalist work: Insomnie (1957) (figure 121). The artist depicts a night time scene of a hilly cemetery which is filled to capacity with white crosses. A green area with white outlines marks each plot. Even in death, a lone skeleton cannot relax and sits awake gazing at the sky thick with stars. The idea came to Durieux when she saw an American military cemetery while riding a bus in southern Italy; she thought that everyone was asleep; "then it occurred to me that maybe one of them wasn't."[17]

Durieux had a keen interest in the political climate at home and abroad. Activities of the Ku Klux Klan disturbed the artist as it did many other southerners. Deep South (1957) (figure 130) is a "take-off' on the KKK15 with its hooded figures and numerous fallen crosses and their ashes.

Durieux's choice of colors,red, white, blue and yellow is also ironic in its intent. Red, white and blue imply patriotism—an emotion which members of the Klan try to evoke their members. Durieux's inclusion of yellow adds a subtle dimension to the lithograph since the color is traditionally associated with cowardice.

Durieux's three trips to Paris were not all spent in the atelier of Desjobert. She also worked on color etching at Lacouriere-Frelaut which was founded in 1929. She worked with Roger Lacouriere—an engraver and master printer whom Stanley William Hayter called "the most highly skilled artisans of colour printing."[17]

Mardi Gras

Caroline Durieux, John McCrady and Ralph Wickiser collaborated on a 1948 book, Mardi Gras Day, published by Henry Holt. Each artist contributed 10 artworks as illustrations for the book. The ten lithographs that Durieux contributed for this book are less satirical than much of her work. When asked about this, Durieux said that Mardi Gras was inherently self-satirical and therefore she decided to present it as is.[18]

Durieux was a fixture at the Mardi Gras Day open house hosted by Lyle Saxon in the St. Charles Hotel. Dressing in costume was a requisite for admission to the party and some of Durieux's images for the book were of attendees.[18]

In 2018 the Hermes parade included a float titled Caroline Durieux that was inspired by Swine Maskers one of the artist's lithographs from the book. The other nine lithographs were: Carnival Ball, Coach Dogs, Death Masker, Five Girls, Night Parade, Queen of the Carnival, Rex, Six o'clock, TruckRiders.[19]

Good Will Ambassador

In August 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt named Nelson A. Rockefeller to head the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA), a new federal agency whose main objective was to strengthen cultural and commercial relations between the U.S and Latin America, in particular Brazil, in order to route Axis influence and secure hemispheric solidarity. Rockefeller appointed Caroline Durieux to accompany an exhibition from the Museum of Modern Art to Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Rio.[7] The art exhibitions being sent to Mexico were imagined differently by many. Were they purely cultural? Were they intended to improve relations between our countries or were they intended to purely advance our strategic political and defense goals? Having spent so much of her career in Cuba and Mexico, Durieux had the language skills and political connections necessary to understand the sensitivities of the target audience. She relayed her concerns back to DC that the promotional poster was too US-centric to be embraced widely and that the accompanying catalog was confusing because works not being exhibited in a given city were illustrated prominently in the all-inclusive book.[20]

Durieux was both savvy and social and she used those skills to make the events successful. She involved local artists, encouraged their input and charmed them with her art talks and symposia. She facilitated acquiring the supplies needed at local level to enable communities to express their visions.[20] What started out as a tone-deaf good intention turned into a healthy dialogue about art among nations.[20]

In the 1950s, Durieux's work in electron printmaking was used as a tool in the Cold War. The Atomic Energy Commission sends an exhibition of Durieux's works around the world to promote the premise that atomic energy can be used to create art rather than weapons.[7]

Innovation

Caroline Durieux was never content with what she had achieved. She was intrigued with experimentation and new frontiers. The Zigrosser book on Durieux's was published n 1949, By 1951 she is experimenting with faculty friends Naomi and Harry Wheeler, a botanist, with ink coated microbes. In 1952 Durieux creates the first electron print using radioactive ink. In the book The Appeal of Prints, Carl Zigrosser hails the technique as an advance in printmaking.

By 1954 Durieux introduces color into the electron printing process with the assistance of faculty friends on the Chemistry faculty, Dr. Olen Nance and Dr. John F. Christman

By 1957, Durieux applies for patent on electron printing. That same year she and Dr. Christman revive the 19th century technique, cliche verre using photographic paper in lieu of glass. Ultimately they devise a way to print color cliche verres using the new technique.

The new techniques were slow to be adopted because many were reluctant to work with the low level of radiation. However, Durieux's experimental work was well received by critics and museums alike.

Teaching and Mentoring

Caroline Durieux was a gifted teacher and devoted mentor for her students first at Newcomb College of Tulane University in New Orleans and then at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. In 1964 she retired as Professor Emeritus but continued seeing and mentoring students at her home near campus until her stroke in 1980. Among her students are five that should be noted.[21]

George Dureau (1930–2014) was a photographer and painter who specialized in black-and-white nude photography of poor athletes, dwarfs and amputees many of whom were black. His photographs appeared before Robert Mapplethorpe became famous for his nude portraits; It is thought that Dureau's work inspired Mapplethorpe. Right-wing extremists' attacks on a Mapplethorpe exhibition helped elevate his profile. In contrast, the conservative high society mavens in New Orleans seemed to accept hanging Dureau's photographs of nude black men alongside their Audubons.

Caroline was having dinner at fellow artist Evelyn Withersoon's (1901–1998) home one night when George Dureau crashed the party to kneel in front of Durieux and present her with a large drawing of a nude cupid endowed with a massive penis – a valentine for his mentor.

Robert Gordy (1933–1986) is considered one of the most original and creative Southern painters of the twentieth century. He was known for his complex acrylic paintings that featured patterning and repetition, and linear shapes in a flat pictorial space in closely-keyed colors. A painter and printmaker, Gordy created a superb series of monotypes at the end of his life.

Aris Koutroulis (1938–2013) grew up during World War II, in Greece, surviving bombings and starvation. That trauma informed his life as a U.S. citizen and as an artist. At Wayne State University, he was a cornerstone of the Printmaking Department where challenged his student's ideas of what art was, while allowing them to question their own personal art-making processes.

In a Smithsonian oral history, Koutroulis stated:

"Caroline Durieux was fantastic – a major influence in my life. I learned from her not only about art but also about life. She was absolutely amazing in her way of life and her way of thinking, the clarity of her mind and her presence of knowing what is and what isn't, what's real and what is illusionistic. She realized my potential. She was responsible for my going to Tamarind. She wrote them "this is a person you should have"."[22]

Elmore Morgan, Jr. (1931–2008) is a painter of the southwest Louisiana prairie in the en plein air tradition, creating a monumental collection of iconic works that capture the vivid palette of that broad landscape under spacious skies. Morgan also was an accomplished photographer. From 1965 to 1998, Morgan taught painting and drawing at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette where he deeply influenced many contemporary Louisiana painters who studied or taught with him. Morgan was a student of Durieux's who evolved into a collector of her lithographs.

Jesselyn Benson Zurik (1916–2012) created paintings, sculptures, and drawings throughout her life and exhibited them worldwide. She excelled in creating assemblages steeped in architectural and industrial patterns. She earned her Design degree from Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University in 1938 where she studied with Caroline Durieux. She was a devotee of lifelong education and was generous in supporting artists, especially in the 1997 establishment of the Jesselyn Zurik Fund for Research at her alma mater, Newcomb College.

Lifelong learning

In the early 1950s, Durieux took a sabbatical leave to study color lithography in Paris. Her decision to seek further study is indicative of Durieux's continuing dedication to the art of printmaking and to a long life of constant learning. During her leave, she traveled throughout Europe to France, Italy, Spain and England. She eventually went to study at the atelier of Edmund Desjobert (d. 1964) and Son in Paris. At first Durieux had difficulty at the workshop because of her gender:

"When I walked in to begin my work, I was given the smallest, oldest stones they could find. At first I was furious, but I used them to make my first images and brought them back in. The master printer seemed to be surprised at my ability—and I was immediately given the best, heaviest limestone they had for my next pieces."

Not only did the director of the workshop notice Durieux's talent but also they were impressed with her ability to speak their language:

"Since I speak French they taught me all kinds of little tricks that they wouldn't tell the other Americans in the group because they didn't like them since they didn't speak French."

She studied with Atelier Desjobert for three months in 1952 and again in 1957. In this new medium of color lithography her work became increasingly abstract, and her satire more subtle and complex. Durieux's color lithographs are more thought-provoking and less whimsical. She said of her work at this time: "I wanted to be more emphatic, more essential. I gradually realized that what you LEAVE OUT is important."

Durieux's interest in death is evident in the sober and minimalist work: Insomnie (1957) (figure 121). The artist depicts a nighttime scene of a hilly cemetery which is filled to capacity with white crosses. A green area with white outlines marks each plot. Even in death, a lone skeleton cannot relax and sits awake gazing at the sky thick with stars. The idea came to Durieux when she saw an American military cemetery while riding a bus in southern Italy; she thought that everyone was asleep; "then it occurred to me that maybe one of them wasn't Durieux had a keen interest in the political climate at home and abroad. Activities of the Ku Klux Klan disturbed the artist as it did many other southerners. Deep South (1957) (figure 130) is a "take-off' on the KKK15 with its hooded figures and numerous fallen crosses and their ashes. Durieux's choice of colors,red, white, blue and yellow is also ironic in its intent. Red, white and blue imply patriotism—an emotion which members of the Klan try to evoke in their members. Durieux's inclusion of yellow adds a subtle dimension to the lithograph since the color is traditionally associated with cowardice. Durieux's three trips to Paris were not all spent in the atelier of Desjobert. She also worked on color etching at Atelier Lacouriere-Frelaut which was founded in 1929. She worked with Roger Lacouriere—an engraver and master printer whom Stanley William Hayter called "the most highly skilled artisans of colour printing"

Death and legacy

Durieux died on November 26, 1989, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.[23] Her papers are held at Louisiana State University[24] and the Archives of American Art.[25]

In 2010, a retrospective, "Caroline Durieux: A Radioactive Wit", was exhibited at the LSU Museum of Art.[26] In 2018, she was profiled in a short film on New Orleans public TV, WYES, as part of the station's "Tricentennial Moments" campaign honoring the city.

The largest collections of Durieux works may be seen in the following museums; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Historic New Orleans Collection, Louisiana State Museum, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, LSU Museum of Art, Louisiana Art and Science Museum, and the Meridian Museum of Art.[7]

Bibliography

- Cox, Richard; Durieux, Caroline (1977). Caroline Durieux: Lithographs of the Thirties and Forties. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University (LSU) Press. ISBN 9780807103722.

- Durieux, Caroline (2008). From Society to Socialism: The Art of Caroline Durieux, March 26-June 15, 2008, Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University (exhibition). Newcomb Art Gallery. Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University. ISBN 9780966859560.

- Caroline Durieux and her Art Conquer Washington,A review of the artist's exhibition at the June 1 Gallery in Washington, DC, July 1979 June 1 Jottings

References

- ↑ Megraw, Richard (January 6, 2011). "Caroline Durieux". KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Sally Main; Adrienne Spinozzi; David Conradsen; Martin Eidelberg; Kevin W. Tucker; Ellen Paul Denker (2013). "Butler, Mary Williams (1873–1937)". The Arts & Crafts of Newcomb Pottery. Skira Rizzoli. p. 27. Retrieved 2021-05-15 – via Issuu.

- ↑ Tucker, Susan; Willinger, Beth (2012-05-07). Newcomb College, 1886–2006: Higher Education for Women in New Orleans. LSU Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-8071-4337-7.

- ↑ "Caroline Durieux papers, [ca.1900–1979]".

- ↑ "Caroline Durieux papers, [ca.1900–1979]".

- 1 2 Durieux, Caroline (1976). "Friends of the Cabildo Oral History Program" (Interview). Adele Ramos. New Orleans, Louisiana: Louisiana State Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Retif, Earl; Main, Sally; Durieux, Caroline (2008). From Society to Socialism: The Art of Caroline Durieux. New Orleans: Newcomb Art Gallery. ISBN 978-0-966-8595-6-0.

- ↑ Pohl, K.A. (2015). Mexico in New Orleans: A Tale of Two Americas. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Museum of Art. p. 11. ISBN 9780807163344.

- ↑ Pohl, K.A. (2015). Mexico in New Orleans: A Tale of Two Americas. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Museum of Art. p. 5. ISBN 9780807163344.

- ↑ Nieves, Marysol. "Lot Essay". Christie's. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ↑ Pohl, K.A. (2015). Mexico in New Orleans: A Tale of Two Americas. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Museum of Art. p. 13. ISBN 9780807163344.

- ↑ Zigrosser, Carl (1942). The Artist in America: 24 Close-ups of Contemporary Printmakers. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ↑ Estill Curtis Pennington (1991). Downriver: currents of style in Louisiana painting, 1800–1950. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88289-800-1.

- ↑ Caroline Wogan Durieux Collection at the LSU Museum of Art, Louisiana Digital Library, Baton Rouge, La. (accessed 21 January 2015) <http://www.louisianadigitallibrary.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/CWD>

- ↑ "Caroline Durieux American (1896–1989)". IFPDA. Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Tucker, Susan; Willinger, Beth (2012-05-07). Newcomb College, 1886–2006: Higher Education for Women in New Orleans. LSU Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-8071-4337-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore, Ann Michelle (1992). "The Life and Work of Caroline Spelman Wogan Durieux (1896–1989)". Masters Abstracts International. 32 (1): 414.

- 1 2 Wickiser, Ralph; Durieux, Caroline; McCrady, John (1948). Mardi Gras Day. New Orleans: Henry Holt.

- ↑ "Caroline Durieux Float In Hermes Parade 2018". Shutterstock. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 Ulloa-Herrera, Olga (2014). "Appendix B" (PDF). THE U.S. STATE, THE PRIVATE SECTOR AND MODERN ART IN SOUTH AMERICA 1940–1943 (Ph.D.). George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ Tucker, Susan; Willinger, Beth (2012-05-07). Newcomb College, 1886–2006: Higher Education for Women in New Orleans. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-4337-7.

- ↑ Koutroulis, Aris (1976). "Oral History Interviews". Smithsonian Archives of American Art (Interview). James Crawford. Smithsonian.

- ↑ "KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, "Caroline Durieux"". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-08.

- ↑ http://www.lib.lsu.edu/special/findaid/3827.pdf

- ↑ "Caroline Durieux papers, [ca.1900–1979]".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Zigrosser, Carl (1942). The Artist in America: Twenty-Four Close-ups of Contemporary Printmakers. New York City, New York: A. A. Knopf.

- Tucker, Susan; Willinger, Beth (2012). "Chapter 16 by Earl Retif". Newcomb College, 1886–2006: Higher Education for Women in New Orleans. Louisiana State University (LSU) Press. p. 344. ISBN 9780807143360.

- Retif, Earl (1990) Caroline Wogan Durieux (1896–1989). Newcomb Under the Oaks, Vol.14, Spring 1990

- Retif, Earl and Main, Sally, Curators(2008),From Society To Socialism, The Art of Caroline Durieux(2008), Newcomb Art Gallery of Tulane University.ISBN 0966859561

- Saxon, Lyle (author) and Durieux, Caroline (artist), Gumbo Ya-Ya: A Collection of Louisiana Folk Tales (1945), ISBN 9780517019221

- Poesch, Jessie J., Printmaking in New Orleans (2006), The Historic New Orleans Collection, ISBN 9781578067688

- Retif, Earl, The Sharpest of Needles, Innovative 20th Century Printmaking by Caroline Durieux, Summer 2008, The Tulanian, Volume 80, pages 28–35

- Kraeft, June and Norman, Durieux and her Art Conquer Washington, June 1 Jottings, July 1979

- Ittmann, John, editor, Shoemaker, Innis, Weschler, James, Williams, Lyle, Mexico and Modern Printmaking, Philadelphia Museum, 2006, ISBN 9780876331949.

- Saltpeter, Harry, About Caroline Durieux: A Southern Girl Whose Pictures Have No Languor, But An Icy Bite, Coronet, June 1937.50

- Wickiser, Ralph, Durieux, Caroline, and McCrady, John, Mardi Gras Day, New York: Henry Holt, 1948

- Zigrosser, Carl, The Appeal of Prints, Kennett Square, PA. KNA Press, 1970

- Jones, Howard Mumford, Books Considered, The New Republic, March 1978, p. 34-35

- Retif, Earl, In Memoriam Caroline Durieux. 1896–1989, From the New Orleans Museum of Art, Journal of the Print World 13 No. 2, Spring 1990, 30.

- Glassman, Elizabeth, and Symmes, Marilyn F., Cliche-Verre, Hand Drawn, Light Printed: A Survey of the Medium from 1839 to the Present, The Detroit Institute of the Arts, 1980

- Phagan, Patricia, editor, The American Scene and the South – Paintings and Works on Paper 1930–1946, Georgia Museum of Art,University of Georgia, 1996, pp. 110–115

- Kraeft, June and Norman, Great American Prints 1900–1950, 138 Lithographs Etchings and Woodcuts, Dover Publications 1984, ISBN 0-486-24661-2 #40

- Faulkner, William and Spratling, William, Sherwood Anderson & Other Famous Creoles; A Gallery of Contemporary New Orleans, Pelican Press, 1926

- Symmes, Marilyn, Paths to the Press, Printmaking and American Women Artists, 1910–1960, Kansas State University, 2006

- Miller, Robin, Setting an Example: Early Female ArtistsCarve Out Their Space Louisiana, The Advocate, March 2022

- Miller, Robin, A Radioactive Wit Exhibition Celebrates Work Caroline Durieux, The Advocate, August 2010

- Franich, Megan, Works of Art, Arts for Work: Caroline Wogan Durieux,the Works Progress Administration and the U.S.State Department (2010),University of New Orleans Thesis and Diaaertation

- Williams, Lynn Barstis, Imprinting the South, Printmakers and Their Images of the Region, 1920s–1940s, University of Alabama Press (2007), ISBN 9780817315603

- Barnwell, Janet Elizabeth, "Narrative patterns of racism and resistance in the work of William Faulkner" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations

- McCash, Doug. "Conflicted Caroline, Ridiculing the Road Not Taken." New Orleans Times Picayune. March 28, 2008

- Beall, Karen and Fern, Alan and Zigrosser, Carl, American Prints in the Library of Congress, A Catalog of the Collection (1970), Johns Hopkins University Press

- Johnson, Una E., American Prints and Printmakers, (1970), Knopf Doubledy, ISBN 9780385149211

- Landau, Ellen, Artists for Victory, (1983), Library of Congress, ISBN 0844404322

- Gambone, Robert L, Art and Popular Religion in Evangelical America, 1915–1942, University of Tennessee Press (1989), p. 102,112,119-124,126,134, ISBN 0-87049-588-7

- Schenck, Kimberly, Cloche-Verre: Drawing and Photography, Topics in Photography Preservation, 1995, Vol. 6 Article 9, p. 112-118

- Borden, Emily, Egner & Koutroulis , Wayne State University eMuseum (2023)

- Seaton, Elizabeth G.,Paths to Press (2006) ISBN 1890751138

- Pfohl,Katie , Mexico in New Orleans: A Tale of Two Americas , LSU Press (2016) ISBN 9780807163344

- Ulloa-Herrera, Olga, THE U.S. STATE, THE PRIVATE SECTOR AND MODERN ART IN SOUTH AMERICA 1940–1943, A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies (2014)

- Laney, Ruth, The Thrill of the Hunt, Country Roads Magazine (2016)

- Paine, Frances Flynn and Abbot, Jere, Exhibition Catalog on Diego Rivera, Museum of Modern Art, Includes illustration of Rivera's portrait of Caroline Durieux, Dec 23, 1931 - Jan 27,1932 (1931)

- Durieux, Caroline, Satirical Paintings and Drawings by Caroline Durieux, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (1944)

- Sadlier, Darlene J., Good Neighbor Cultural Diplomacy in world War II: The Art of Making Friends, Indiana University

- Retif, Earl, In Memoriam, Caroline Durieux (1896–1989) Rare Works by the Artist at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Journal of the Print World (1990)

- Rivera, Diego, On The Work of Caroline Durieux, Mexican Folkways, Sonora News Company (1929)

- Beals Carleton, The Art of Caroline Durieux, Mexican Life (1934)

- Pope, John, Caroline Durieux's World, New Orleans States-Item, November 1978

- Hoffman, Louise C., Caroline Durieux, A Portrait of the Artist, The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly, (Spring 1992)

- Durieux, Caroline, An Inquiry into the Nature of Satire, Twenty-four Satirical Lithographs, Master of Arts Thesis, Department of Fine Arts (May 1949)

External links

- Video: Caroline Durieux, Tricentennial Moment (2018) by WYES-TV (PBS)

- Salzer, Adele Ramos, Caroline Durieux Interview, Friends of the Cabildo Oral History Program, Louisiana State Museum (1976)