_underway_on_8_April_2017.JPG.webp)

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

|

| Ships of the United States Navy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ships in current service | |

| Ships grouped alphabetically | |

| Ships grouped by type | |

The history of the United States Navy divides into two major periods: the "Old Navy", a small but respected force of sailing ships that became notable for innovation in the use of ironclads during the American Civil War, and the "New Navy" the result of a modernization effort that began in the 1880s and made it the largest in the world by 1943.[1][2]

The United States Navy claims October 13, 1775 as the date of its official establishment, when the Second Continental Congress passed a resolution creating the Continental Navy. With the end of the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Navy was disbanded. Under the Presidency of George Washington, merchant shipping came under threat while in the Mediterranean by Barbary pirates from four North African States. This led to the Naval Act of 1794, which created a permanent standing U.S. Navy. The original six frigates were authorized as part of the Act. Over the next 20 years, the Navy fought the French Republic Navy in the Quasi-War (1798–99), Barbary states in the First and Second Barbary Wars, and the British in the War of 1812. After the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy was at peace until the Mexican–American War in 1846, and served to combat piracy in the Mediterranean and Caribbean seas, as well as fighting the slave trade off the coast of West Africa. In 1845, the Naval Academy was founded at old Fort Severn at Annapolis, Maryland by the Chesapeake Bay. In 1861, the American Civil War began and the U.S. Navy fought the small Confederate States Navy with both sailing ships and new revolutionary ironclad ships while forming a blockade that shut down the Confederacy's civilian coastal shipping. After the Civil War, most of its ships were laid up in reserve, and by 1878, the Navy was just 6,000 men.

In 1882, the U.S. Navy consisted of many outdated ship designs. Over the next decade, Congress approved building multiple modern steel-hulled armored cruisers and battleships, and by around the start of the 20th century had moved from twelfth place in 1870 to fifth place in terms of numbers of ships. Most sailors were foreigners. After winning two major battles during the 1898 Spanish–American War, the American Navy continued to build more ships, and by the end of World War I had more men and women in uniform than the British Royal Navy.[3] The Washington Naval Conference of 1921 recognized the Navy as equal in capital ship size to the Royal Navy, and during the 1920s and 1930s, the Navy built several aircraft carriers and battleships. The Navy was drawn into World War II after the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and over the next four years fought many historic battles including the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Battle of Midway, multiple naval battles during the Guadalcanal Campaign, and the largest naval battle in history, the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Much of the Navy's activity concerned the support of landings, not only with the "island-hopping" campaign in the Pacific, but also with the European landings. When the Japanese surrendered, a large flotilla entered Tokyo Bay to witness the formal ceremony conducted on the battleship Missouri, on which officials from the Japanese government signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender. By the end of the war, the Navy had over 1,600 warships.

After World War II ended, the U.S. Navy entered the 45 year long Cold War and participated in the Korean and Vietnam proxy wars. Nuclear power and ballistic missile technology led to new ship propulsion and weapon systems, which were used in the Nimitz-class aircraft carriers and Ohio-class submarines. By 1978, the number of ships had dwindled to less than 400, many of which were from World War II, which prompted Ronald Reagan to institute a program for a modern, 600-ship Navy. Following the 1990-91 collapse of the Soviet Union the Soviet Navy was divided among the former Soviet Republics and was left without funding, which made the United States the world's undisputed naval superpower, with the ability to engage and project power in two simultaneous limited wars along separate fronts. This ability was demonstrated during the First and Second Persian Gulf Wars.

In March 2007, the U.S. Navy reached its smallest fleet size, with 274 ships, since World War I. Former U.S. Navy admirals who head the U.S. Naval Institute have raised concerns about what they see as the ability to respond to 'aggressive moves by Iran and China.'[4][5] The United States Navy was overtaken by the Chinese People's Liberation Army Navy in terms of raw number of ships in 2020.[6]

Foundations of the "Old Navy"

Continental Navy (1775–1785)

Resolved, That a swift sailing vessel, to carry ten carriage guns, and a proportionable number of swivels, with eighty men, be fitted, with all possible despatch, for a cruise of three months, and that the commander be instructed to cruize eastward, for intercepting such transports as may be laden with warlike stores and other supplies for our enemies, and for such other purposes as the Congress shall direct.

That a Committee of three be appointed to prepare an estimate of the expence, and lay the same before the Congress, and to contract with proper persons to fit out the vessel.

Resolved, that another vessel be fitted out for the same purposes, and that the said committee report their opinion of a proper vessel, and also an estimate of the expence.

Resolution of the Continental Congress that marked the establishment of what is now the United States Navy.[7]

The Navy was rooted in the American seafaring tradition, which produced a large community of sailors, captains and shipbuilders during the colonial era.[8] During the Revolution, several states operated their own navies. On June 12, 1775, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a resolution creating a navy for the colony of Rhode Island. The same day, Governor Nicholas Cooke signed orders addressed to Captain Abraham Whipple, commander of the sloop Katy, and commodore of the armed vessels employed by the government.[9]

The first formal movement for the creation of the Continental Navy came from Rhode Island, because the widespread smuggling activities of Rhode Island merchants had been increasing suppressed by the British Royal Navy. On August 26, 1775, Rhode Island passed a resolution that there be a single Continental fleet funded by the Continental Congress.[10] The resolution was introduced in the Continental Congress on October 3, 1775, but was tabled. In the meantime, George Washington had begun to acquire ships, starting with the schooner USS Hannah that was paid for out of Washington's own pocket.[9] Hannah was commissioned and launched on September 5, 1775, under the command of Captain Nicholson Broughton, from the port of Marblehead, Massachusetts.[11]

The US Navy recognizes October 13, 1775, as the date of its official establishment—the date of the passage of the resolution of the Continental Congress at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that created the Continental Navy.[7] On this day, Congress authorized the purchase of two vessels to be armed for a privateering cruise against British merchant shipping.[12] On December 13, 1775, Congress authorized the building of thirteen frigates within the next three months, five ships of 32 guns, five with 28 guns and three with 24 guns.[13]

On Lake Champlain, Benedict Arnold ordered the construction of 12 naval vessels to slow down the progress of British forces which had entered New York from Canada. In the ensuing engagement, a Royal Navy fleet decisively defeated Arnold's ships after two days of fighting, but the battle managed to slow down the progression of British ground forces in New York.[14] By mid-1776, a number of ships, ranging up to and including the thirteen frigates approved by Congress, were under construction, but their effectiveness was limited; they were completely outmatched by the Royal Navy, and nearly all were captured or sunk by 1781.[15]

American privateers had some success, with 1,697 letters of marque being issued by Congress. Individual states, American agents in Europe and in the Caribbean also issued commissions; taking duplications into account more than 2,000 commissions were issued by various sources. Over 2,200 British merchant ships were captured by American privateers during the war, amounting to almost $66 million, a significant sum at the time.[16]

One particularly notable American naval officer of the Revolutionary War was John Paul Jones, who a voyage around the British Isles captured the Royal Navy frigate Serapis (1779) in the Battle of Flamborough Head. Partway through the battle, with the rigging of the two ships entangled, and several guns of Jones' ship Bonhomme Richard (1765) out of action, the captain of Serapis asked Jones if he had struck his colors, to which Jones has been quoted as replying, "I have not yet begun to fight!"[17]

France officially entered the war on June 17, 1778, and ships of the French Navy sent to the Western Hemisphere spent most of the year in the West Indies, and only sailed near the Thirteen Colonies during the Caribbean hurricane season from July until November. A French Navy fleet attempted landings in New York and Rhode Island in 1778, but ultimately failed to engage British forces.[18] In 1779, a fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Charles Henri, comte d'Estaing assisted American forces attempting to recapture Savannah, Georgia.[19]

In 1780, a fleet with 6,000 troops commanded by Lieutenant General Jean-Baptiste, comte de Rochambeau landed at Newport, Rhode Island, and shortly afterwards the fleet was blockaded by the Royal Navy. In early 1781, Washington and de Rochambeau planned an attack against the British in the Chesapeake Bay area to coordinate with the arrival of a large fleet commanded by Vice Admiral François, comte de Grasse. Successfully deceiving the British that an attack was planned in New York, Washington and de Rochambeau marched to Virginia, and de Grasse began landing forces near Yorktown, Virginia. On September 5, 1781 a major naval action was fought by de Grasse and the British at the Battle of the Virginia Capes, ending with the French fleet in control of the Chesapeake Bay. The Continental Navy continued to interdict British supply ships until peace was finally declared in late 1783.[20]

Disarmament (1785–1794)

The Revolutionary War was ended by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and by 1785 the Continental Navy was disbanded and the remaining ships were sold. The frigate Alliance, which had fired the last shots of the American Revolutionary War, was also the last ship in the Navy. A faction within Congress wanted to keep the ship, but the new nation did not have the funds to keep her in service. Other than a general lack of money, factors for the disarmament of the navy were the loose confederation of the states, a change of goals from war to peace, and more domestic and fewer foreign interests.[22]

After the American Revolutionary War, the brand-new United States struggled to stay financially afloat. National income was desperately needed and most came from tariffs on imported goods. Because of rampant smuggling, the need was immediate for strong enforcement of tariff laws.[23] On August 4, 1790, the United States Congress, urged on by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, created the Revenue-Marine, the forerunner for the United States Coast Guard, to enforce the tariff and all other maritime laws.[24] Ten cutters were initially ordered.[25] Between 1790 and 1797 when the Navy Department was created, the Revenue-Marine was the only armed maritime service for the United States.[26]

American merchant shipping had been protected by the Royal Navy during the colonial era, but as a consequence of the Treaty of Paris and the disarmament of the Continental Navy, the United States no longer had any protection for its ships from pirates. The fledgling nation did not have the funds to pay annual tribute to the Barbary states, so their ships were vulnerable for capture after 1785. By 1789, the new Constitution of the United States authorized Congress to create a navy, but during George Washington's first term (1787–1793) little was done to rearm the navy.[27] In 1793, the French Revolutionary Wars between Great Britain and France began, and a truce negotiated between Portugal and Algiers ended Portugal's blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar which had kept the Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean. Soon after, the pirates sailed into the Atlantic, and captured 11 American merchant ships and more than a hundred seamen.[28]

In reaction to the seizure of the American vessels, Congress debated and approved the Naval Act of 1794, which authorized the building of six frigates, four of 44 guns and two of 36 guns. Supporters were mostly from the northern states and the coastal regions, who argued the Navy would result in savings in insurance and ransom payments, while opponents from southern states and inland regions thought a navy was not worth the expense and would drive the United States into more costly wars.[28]

Establishment (1794–1812)

After the passage of the Naval Act of 1794, work began on the construction of the six frigates: USS United States, President, Constellation, Chesapeake, Congress, and Constitution. Constitution, launched in 1797 and the most famous of the six, was nicknamed "Old Ironsides" (like the earlier HMS Britannia) and, thanks to the efforts of Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., is still in existence today, anchored in Boston harbor. Soon after the bill was passed, Congress authorized $800,000 to obtain a treaty with the Algerians and ransom the captives, triggering an amendment of the Act which would halt the construction of ships if peace was declared. After considerable debate, three of the six frigates were authorized to be completed: United States, Constitution and Constellation.[29] However, the first naval vessel to sail was USS Ganges, on May 24, 1798.[30]

At the same time, tensions between the U.S. and France developed into the Quasi-War, which originated from the Treaty of Alliance (1778) that had brought the French into the Revolutionary War. The United States preferred to take a position of neutrality in the conflicts between France and Britain, but this put the nation at odds with both the British and French. After the Jay Treaty was signed with Great Britain in 1794, France began to side against the United States and by 1797 they had seized over 300 American vessels. The newly inaugurated President John Adams took steps to deal with the crisis, working with Congress to finish the three almost-completed frigates, approving funds to build the other three, and attempting to negotiate an agreement similar to the Jay Treaty with France. The XYZ Affair originated with a report distributed by Adams where alleged French agents were identified by the letters X, Y, and Z who informed the delegation a bribe must be paid before the diplomats could meet with the foreign minister, and the resulting scandal increased popular support in the country for a war with France.[29] Concerns about the War Department's ability to manage a navy led to the creation of the Department of the Navy, which was established on April 30, 1798.[30]

The war with France was fought almost entirely at sea, mostly between privateers and merchant ships.[31] The first victory for the United States Navy was on July 7, 1798 when USS Delaware captured the French privateer Le Croyable, and the first victory over an enemy warship was on February 9, 1799 when the frigate Constellation captured the French frigate L'Insurgente.[30] By the end of 1800, peace with France had been declared, and in 1801, to prevent a second disarmament of the Navy, the outgoing Federalist administration rushed through Congress an act authorizing a peacetime navy for the first time, which limited the navy to six active frigates and seven in ordinary, as well as 45 officers and 150 midshipmen. The remainder of the ships in service were sold and the dismissed officers were given four months pay.[32]

The problems with the Barbary states had never gone away, and on May 10, 1801 the Tripolitans declared war on the United States by chopping down the flag in front of the American Embassy, which began the First Barbary War.[33] USS Philadelphia was captured by the Moors, but then set on fire in an American raid led by Stephen Decatur.[34] The Marines invaded the "shores of Tripoli" in 1805, capturing the city of Derna, the first time the U.S. flag ever flew over a foreign conquest.[35] This act was enough to induce the Barbary rulers to sign peace treaties.[36] Subsequently, the Navy was greatly reduced for reasons of economy, and instead of regular ships, many gunboats were built, intended for coastal use only. This policy proved completely ineffective within a decade.[37]

President Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican party opposed a strong navy, arguing that the small gunboats stationed in the major Atlantic harbors, part of first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton's U.S. Revenue-Marine, were all the nation needed to defend itself. However, this small fleet of lightly armed revenue cutters, which Hamilton had proposed in Federalist Papers No. 11 & 12, was insufficient as a wartime naval force for the needs of the new United States of America.[38]

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the Royal Navy had begun to impress sailors from American ships who they alleged were British deserters; an estimated 10,000 sailors were impressed this way between 1799 and 1812.[39] In 1807, in the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, HMS Leopard demanded that Chesapeake submit to an inspection for British deserters onboard, which was rejected. Leopard responded by opening fire on Chesapeake, and forcibly searched the ship, detaining a number of alleged British subjects. The most violent of many such encounters, the affair further fueled the tensions between the two nations and in June 1812 the U.S. declared war on Britain.[40]

War of 1812 (1812–1815)

Much of the war was expected to be fought at sea; and within an hour of the announcement of war, the diminutive U.S. Navy set forth to do battle with an opponent outnumbering it 50-to-1. After two months, Constitution sank HMS Guerriere; Guerriere's crew were most dismayed to see their cannonballs bouncing off Constitution's unusually strong live oak hull, giving her the enduring nickname of "Old Ironsides".[41] On December 29, 1812 Constitution defeated HMS Java off the coast of Brazil and Java was burned after the Americans determined she could not be salvaged. On October 25, 1812, United States captured HMS Macedonian; after the battle Macedonian was captured and entered into American service.[42] In 1813, USS Essex commenced a very fruitful raiding venture into the South Pacific under the command of David Porter, preying upon the British merchant and whaling industry. Essex was already known for her capture of HMS Alert and a British transport the previous year, and gained further success capturing 15 British merchant ships. The British finally took action, dispatching HMS Cherub and HMS Phoebe to stop the Essex. The two ships, under the command of Sir James Hillyar, blockaded Essex before Porter ordered his ship to attempt to escape; in the ensuing battle, Essex was captured by the British.[43]

The capture of the three Royal Navy frigates led the British to deploy more vessels on the American seaboard to tighten their blockade of U.S. ports.[44] On June 1, 1813, off Boston Harbor, the American frigate Chesapeake, commanded by Captain James Lawrence, was captured by the British frigate HMS Shannon under Captain Sir Philip Broke. Lawrence was mortally wounded and famously cried out, "Don't give up the ship!".[45] Despite their earlier successes, by 1814 many of the Navy's best ships were blockaded in port and unable to prevent British incursions on land via the sea.[46]

During the summer of 1814, the British fought the Chesapeake Campaign, which was climaxed by amphibious assaults against Washington and Baltimore. The capital fell to the British almost without a fight, and several American warships were burned at the Washington Navy Yard, including the 44-gun frigate USS Columbia. At Baltimore, the bombardment by Fort McHenry inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner", and the hulks blocking the channel prevented the fleet from entering the harbor; the army reembarked on the ships, ending the battle.[46]

The American naval victories at the Battle of Lake Champlain and Battle of Lake Erie halted the final British offensive in the north and helped to deny the British exclusive rights to the Great Lakes in the Treaty of Ghent.[47] Shortly before the treaty was signed, President was captured by four British frigates. Three days after the treaty was signed, Constitution captured HMS Levant and Cyane. The final naval action of the war occurred almost five months after the treaty on June 30, 1815 when the sloop USS Peacock captured the East India Company brig Nautilus,[48] the last enemy ship captured by the U.S. Navy until World War II.

Continental Expansion (1815–1861)

After the war, the Navy's accomplishments paid off in the form of better funding, and it embarked on the construction of many new ships. However, the expense of the larger ships was prohibitive, and many of them stayed in shipyards half-completed, in readiness for another war, until the Age of Sail had almost completely passed. The main force of the Navy continued to be large sailing frigates with a number of smaller sloops during the three decades of peace. By the 1840s, the Navy began to adopt steam power and shell guns, but they lagged behind the French and British in adopting the new technologies.[49]

Enlisted sailors during this time included many foreign-born men, and native-born Americans were usually social outcasts who had few other employment options or they were trying to escape punishment for crimes. In 1835, almost 3,000 men sailed with merchant ships out of Boston harbor, but only 90 men were recruited by the Navy. It was unlawful for black men to serve in the Navy, but the shortage of men was so acute this law was frequently ignored.[50]

Discipline followed the customs of the Royal Navy but punishment was much milder than typical in European navies. Sodomy was rarely prosecuted. The Army abolished flogging as a punishment in 1812, but the Navy kept it until 1850.[51][52]

During the War of 1812, the Barbary states took advantage of the weakness of the United States Navy to again capture American merchant ships and sailors. After the Treaty of Ghent was signed, the United States looked at ending the piracy in the Mediterranean which had plagued American merchants for two decades. On March 3, 1815, Congress authorized deployment of naval power against Algiers, beginning the Second Barbary War. Two powerful squadrons under the command of Commodores Decatur and William Bainbridge, including the 74-gun ships of the line Washington, Independence, and Franklin, were dispatched to the Mediterranean. Shortly after departing Gibraltar en route to Algiers, Decatur's squadron encountered the Algerian flagship Meshuda, and, in the Action of 17 June 1815, captured it. Not long afterward, the American squadron likewise captured the Algerian brig Estedio in the Battle off Cape Palos. By June, the squadrons had reached Algiers and peace was negotiated with the Dey, including a return of captured vessels and men, a guarantee of no further tributes and a right to trade in the region.[53]

Piracy in the Caribbean sea was also a major problem, and between 1815 and 1822 an estimated 3,000 ships were captured by pirates. In 1819, Congress authorized President James Madison to deal with this threat, and since many of the pirates were privateers of the newly independent states of Latin America, he decided to embark on a strategy of diplomacy backed up by the guns of the Navy.[53] An agreement with Venezuela was reached in 1819, but ships were still regularly captured until a military campaign by the West India Squadron, under the command of David Porter, used a combination of large frigates escorting merchant ships backed by many small craft searching small coves and islands, and capturing pirate vessels. During this campaign USS Sea Gull became the first steam-powered ship to see combat action.[54] Although isolated instances of piracy continued into the 1830s, by 1826 the frequent attacks had ended and the region was declared free for commerce.[55]

Another international problem was the slave trade, and the African squadron was formed in 1820 to deal with this threat. Politically, the suppression of the slave trade was unpopular, and the squadron was withdrawn in 1823 ostensibly to deal with piracy in the Caribbean, and did not return to the African coast until the passage of the Webster–Ashburton treaty with Britain in 1842. After the treaty was passed, the United States used fewer ships than the treaty required, ordered the ships based far from the coast of Africa, and used ships that were too large to operate close to shore. Between 1845 and 1850, the United States Navy captured only 10 slave vessels, while the British captured 423 vessels carrying 27,000 captives.[56]

Congress formally authorized the establishment of the United States Military Academy in 1802, but it took almost 50 years to approve a similar school for naval officers.[57] During the long period of peace between 1815 and 1846, midshipmen had few opportunities for promotion, and their warrants were often obtained via patronage. The poor quality of officer training in the U.S. Navy became visible after the Somers Affair, an alleged mutiny aboard the training ship USS Somers in 1842, and the subsequent execution of midshipman Philip Spencer.[58] George Bancroft, appointed Secretary of the Navy in 1845, decided to work outside of congressional approval and create a new academy for officers. He formed a council led by Commodore Matthew Perry to create a new system for training officers, and turned the old Fort Severn at Annapolis into a new institution in 1845 which would be designated as the United States Naval Academy by Congress in 1851.[57]

Naval forces participated in the effort to forcibly move the Seminole Indians from Florida to a reservation west of the Mississippi. After a massacre of army soldiers near Tampa on December 28, 1835, marines and sailors were added to the forces which fought the Second Seminole War from 1836 until 1842. A "mosquito fleet" was formed in the Everglades out of various small craft to transport a mixture of army and navy personnel to pursue the Seminoles into the swamps. About 1,500 soldiers were killed during the conflict, some Seminoles agreed to move but a small group of Seminoles remained in control of the Everglades and the area around Lake Okeechobee.[59]

The Navy played a role in two major operations of the Mexican–American War (1845–1848); during the Battle of Veracruz, it transported the invasion force that captured Veracruz by landing 12,000 troops and their equipment in one day, leading eventually to the capture of Mexico City, and the end of the war. Its Pacific Squadron's ships facilitated the capture of California.[60]

In 1853, Perry led the Perry Expedition, a squadron of four ships which sailed to Japan to establish normal relations with Japan. Perry's two technologically advanced steam-powered ships and calm, firm diplomacy convinced Japan to end three centuries of isolation and sign the Treaty of Kanagawa with the U.S. in 1854. Nominally a treaty of friendship, the agreement soon paved the way for the opening of Japan and normal trade relations with the United States and Europe.[61]

American Civil War (1861–1865)

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen resigned or were dismissed from the United States Navy and went on to serve the Confederacy.[62] On April 20, 1861, the Union burned its ships that were at the Norfolk Navy Yard to prevent their capture by the Confederates, but not all of the ships were completely destroyed.[63] The screw frigate USS Merrimack was so hastily scuttled that her hull and steam engine were basically intact, which gave the South's Stephen Mallory the idea of raising her and then armoring the upper sides with iron plate. The resulting ship was named CSS Virginia. Meanwhile, John Ericsson had similar ideas, and received funding to build USS Monitor.[64]

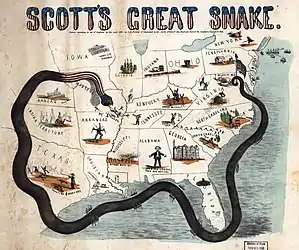

Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the U.S. Army at the beginning of the war, devised the Anaconda Plan to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible. His idea was that a Union blockade of the main ports would weaken the Confederate economy; then the capture of the Mississippi River would split the South. Lincoln adopted the plan in terms of a blockade to squeeze to death the Confederate economy, but overruled Scott's warnings that his new army was not ready for an offensive operation because public opinion demanded an immediate attack.[65]

On March 8, 1862, the Confederate Navy initiated the first combat between ironclads when Virginia successfully attacked the blockade. The next day, Monitor engaged Virginia in the Battle of Hampton Roads. Their battle ended in a draw, and the Confederacy later lost Virginia when the ship was scuttled to prevent capture. Monitor was the prototype for the monitor warship and many more were built by the Union Navy. While the Confederacy built more ironclad ships during the war, they lacked the ability to build or purchase ships that could effectively counter the monitors.[66]

Along with ironclad ships, the new technologies of naval mines, which were known as torpedoes after the torpedo eel, and submarine warfare were introduced during the war by the Confederacy. During the Battle of Mobile Bay, mines were used to protect the harbor and sank the Union monitor USS Tecumseh. After Tecumseh sank, Admiral David G. Farragut famously said, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!".[67] The forerunner of the modern submarine, CSS David, attacked USS New Ironsides using a spar torpedo. The Union ship was barely damaged and the resulting geyser of water put out the fires in the submarine's boiler, rendering the submarine immobile. Another submarine, CSS H.L. Hunley, was designed to dive and surface but ultimately did not work well and sank on five occasions during trials. In action against USS Housatonic the submarine successfully sank its target but was lost by the same explosion.[68]

The Confederates operated a number of commerce raiders and blockade runners, CSS Alabama being the most famous, and British investors built small, fast blockade runners that traded arms and luxuries brought in from Bermuda, Cuba, and The Bahamas in return for high-priced cotton and tobacco. When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner, the ship and cargo were sold and the proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen were mostly British and they were simply released.[69]

The blockade of the South caused the Southern economy to collapse during the war. Shortages of food and supplies were caused by the blockade, the failure of Southern railroads, the loss of control of the main rivers, and foraging by Union and Confederate armies. The standard of living fell even as large-scale printing of paper money caused inflation and distrust of the currency. By 1864 the internal food distribution had broken down, leaving cities without enough food and causing food riots across the Confederacy. The Union victory at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher in January 1865 closed the last useful Southern port, virtually ending blockade running and hastening the end of the war.[70]

Decline of the Navy (1865–1882)

After the war, the Navy went into a period of decline. In 1864, the Navy had 51,500 men in uniform,[71] and almost 700 ships and about 60 monitor-type coastal ironclads which made the U.S. Navy the second largest in the world after the Royal Navy.[72] By 1880 the Navy only had 48 ships in commission, 6,000 men, and the ships and shore facilities were decrepit but Congress saw no need to spend money to improve them.[73] The Navy was unprepared to fight a major maritime war before 1897.[74]

In 1871, an expedition of five warships commanded by Rear Admiral John Rodgers was sent to Korea to obtain an apology for the murders of several shipwrecked American sailors and secure a treaty to protect shipwrecked foreigners in the future. After a small skirmish, Rodgers launched an amphibious assault of approximately 650 men on the forts protecting Seoul. Despite the capture of the forts, the Koreans refused to negotiate, and the expedition was forced to leave before the start of typhoon season.[75] Nine sailors and six marines received Medals of Honor for their acts of heroism during the Korean campaign; the first for actions in a foreign conflict.[76]

By the 1870s most of the ironclads from the Civil War were laid up in reserve, leaving the United States virtually without an ironclad fleet. When the Virginius Affair first broke out in 1873, a Spanish ironclad happened to be anchored in New York Harbor, leading to the uncomfortable realization on the part of the U.S. Navy that it had no ship capable of defeating such a vessel. The Navy hastily issued contracts for the construction of five new ironclads, and accelerated its existing repair program for several more.[77]

By the time the Garfield administration assumed office in 1881, the Navy's condition had deteriorated still further. A review conducted on behalf of the new Secretary of the Navy, William H. Hunt, found that of 140 vessels on the Navy's active list, only 52 were in an operational state, of which a mere 17 were iron-hulled ships, including 14 aging Civil War era ironclads. Hunt recognized the necessity of modernizing the Navy, and set up an informal advisory board to make recommendations.[78] Also to be expected, morale was considerably down; officers and sailors in foreign ports were all too aware that their old wooden ships would not survive long in the event of war. The limitations of the monitor type effectively prevented the United States from projecting power overseas, and until the 1890s the United States would have come off badly in a conflict with even Spain or the Latin American powers.[79][80]

"New Navy"

Rebuilding (1882–1898)

In 1882, on the recommendation of an advisory panel, the Navy Secretary William H. Hunt requested funds from Congress to construct modern ships. The request was rejected initially, but in 1883 Congress authorized the construction of three protected cruisers, USS Chicago, USS Boston, and USS Atlanta, and the dispatch vessel USS Dolphin, together known as the ABCD ships.[81] In 1885, two more protected cruisers, USS Charleston and USS Newark which was the last American cruiser to be fitted with a sail rig, were authorized. Congress also authorized the construction of the first battleships in the Navy, USS Texas and USS Maine. The ABCD ships proved to be excellent vessels, and the three cruisers were organized into the Squadron of Evolution, popularly known as the White Squadron because of the color of the hulls, which was used to train a generation of officers and men.[82] Before 1910, when an apprenticeship system was established, most enlisted sailors were foreign mercenaries who spoke little English.[83]

Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan's book The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783, published in 1890 had momentous impact on major navies around the globe. In the United States it justified Expansion to both the government and the general public. With the closing of the frontier, geographical expansionists had to look outwards, to the Caribbean, to Hawaii and the Pacific, and with the doctrine of Manifest Destiny as philosophical justification, many saw the Navy as an essential part of realizing that doctrine beyond the limits of the American continent.[84]

In 1890, Mahan's doctrine influenced Navy Secretary Benjamin F. Tracy to propose the United States start building no less than 200 ships of all types, but Congress rejected the proposal. Instead, the Navy Act of 1890 authorized building three battleships, USS Indiana, USS Massachusetts, and USS Oregon, followed by USS Iowa. By around the start of the 20th century, two Kearsarge-class battleships and three Illinois-class battleships were completed or under construction, which brought the U.S. Navy from twelfth place in 1870[85] to fifth place among the world's navies.[86]

Battle tactics, especially long-range gunnery, became a central concern.[87] USS Puritan and the four Amphitrite-class monitors, originally ordered after the 1873 Virginius war scare, were completed in the 1880s and 1890s. They were followed by the USS Monterey and the Arkansas-class monitors. All of these vessels except the Arkansas-class would later take part in the Spanish–American War of 1898.[77] The development of the modern torpedo in Europe between 1866 and 1890 would also lead the Navy to build 35 steam-powered torpedo boats between 1890 and 1901 for coastal defense.[88]

Spanish–American War (1898)

The United States was interested in purchasing colonies from Spain, specifically Cuba, but Spain refused. Newspapers wrote stories, many which were fabricated, about atrocities committed in Spanish colonies which raised tensions between the two countries. A riot gave the United States an excuse to send Maine to Cuba, and the subsequent explosion of the ship in Havana Harbor increased popular support for war with Spain. The cause of the explosion was investigated by a board of inquiry, which in March 1898 came to the conclusion the explosion was caused by a sea mine, and there was pressure from the public to blame Spain for sinking the ship. However, later investigations pointed to an internal explosion in one of the magazines caused by heat from a fire in the adjacent coal bunker.[89]

Assistant Navy secretary Theodore Roosevelt quietly positioned the Navy for attack before the Spanish–American War was declared in April 1898. The Asiatic Squadron, under the command of George Dewey, immediately left Hong Kong for the Philippines, attacking and decisively defeating the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay. A few weeks later, the North Atlantic Squadron destroyed the majority of heavy Spanish naval units in the Caribbean in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba.[90]

The Navy's experience in this war was encouraging in that it had won but also cautionary in that the enemy had one of the weakest of the world's modern fleets. Also, the Manila Bay attack was extremely risky in which the American ships could have incurred severe damage or run out of supplies, as they were 7,000 miles from the nearest American harbor. That would have a profound effect on Navy strategy and American foreign policy for next several decades.[91]

Rise of the Modern Navy (1898–1914)

Fortunately for the New Navy, its most ardent political supporter, Theodore Roosevelt, became President in 1901. Under his administration, the Navy went from the sixth largest in the world to second only to the Royal Navy.[92] Theodore Roosevelt's administration became involved in the politics of the Caribbean and Central America, with interventions in 1901, 1902, 1903, and 1906. At a speech in 1901, Roosevelt said, "Speak softly and carry a big stick, you will go far", which was a cornerstone of diplomacy during his presidency.[93]

Roosevelt believed that a U.S.-controlled canal across Central America was a vital strategic interest to the U.S. Navy, because it would significantly shorten travel times for ships between the two coasts. Roosevelt was able to reverse a decision in favor of a Nicaraguan Canal and instead moved to purchase the failed French effort across the Isthmus of Panama. The isthmus was controlled by Colombia, and in early 1903, the Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed by both nations to give control of the canal to the United States. After the Colombian Senate failed to ratify the treaty, Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the US Navy would assist their cause for independence. Panama proceeded to proclaim its independence on November 3, 1903, and USS Nashville impeded any interference from Colombia. The victorious Panamanians allowed the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone on February 23, 1904, for US$10 million.[94] The naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba was built in 1905 to protect the canal.[95]

The latest technological innovation of the time, submarines, were developed in the state of New Jersey by an Irish-American inventor, John Philip Holland. His submarine, USS Holland was officially commissioned into U.S. Navy service in the fall of 1900.[96] The Russo-Japanese War of 1905 and the launching of HMS Dreadnought in the following year lent impetus to the construction program. At the end of 1907 Roosevelt had sixteen new pre-dreadnought battleships to make up his "Great White Fleet", which he sent on a cruise around the world. While nominally peaceful, and a valuable training exercise for the rapidly expanding Navy, it was also useful politically as a demonstration of United States power and capabilities; at every port, the politicians and naval officers of both potential allies and enemies were welcomed on board and given tours. The cruise had the desired effect, and American power was subsequently taken more seriously.[96][97]

The voyage taught the Navy more fueling stations were needed around the world, and the strategic potential of the Panama Canal, which was completed in 1914. The Great White Fleet required almost 50 coaling ships, and during the cruise most of the fleet's coal was purchased from the British, who could deny access to fuel during a military crisis as they did with Russia during the Russo-Japanese War.[98]

World War I (1914–1918)

Mexico

When United States agents discovered that the German merchant ship Ypiranga was carrying illegal arms to Mexico, President Wilson ordered the Navy to stop the ship from docking at the port of Veracruz. On April 21, 1914, a naval brigade of marines and sailors occupied Veracruz. A total of 55 Medals of Honor were awarded for acts of heroism at Veracruz, the largest number ever granted for a single action.[99]

Preparing for war 1914–1917

Despite U.S. declarations of neutrality and German accountability for its unrestricted submarine warfare, in 1915 the British passenger liner Lusitania was sunk, leading to calls for war.[100] President Wilson forced the Germans to suspend unrestricted submarine warfare and after long debate Congress passes the Naval Act of 1916 that authorized a $500 million construction program over three years for 10 battleships, 6 battlecruisers, 10 scout cruisers, 50 destroyers and 67 submarines.[101] The idea was a balanced fleet, but in the event destroyers were much more important, because they had to handle submarines and convoys. By the end of the war 273 destroyers had been ordered; most were finished after World War I ended but many served in World War II.[102] There were few war plans beyond the defense of the main American harbors.[103]

Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels, a pacifistic journalist, had built up the educational resources of the Navy and made its Naval War College an essential experience for would-be admirals. However, he alienated the officer corps with his moralistic reforms (no wine in the officers' mess, no hazing at Annapolis, more chaplains and YMCAs). Ignoring the nation's strategic needs, and disdaining the advice of its experts, Daniels suspended meetings of the Joint Army and Navy Board for two years because it was giving unwelcome advice. He chopped in half the General Board's recommendations for new ships, reduced the authority of officers in the Navy yards where ships were built and repaired, and ignored the administrative chaos in his department. Bradley Fiske, one of the most innovative admirals in American naval history, was Daniels' top aide in 1914; he recommended a reorganization that would prepare for war, but Daniels refused. Instead, he replaced Fiske in 1915 and brought in for the new post of Chief of Naval Operations an unknown captain, William S. Benson. Chosen for his compliance, Benson proved a wily bureaucrat who was more interested in preparing for an eventual showdown with Britain than an immediate one with Germany.

In 1915 Daniels set up the Naval Consulting Board headed by Thomas Edison to obtain the advice and expertise of leading scientists, engineers, and industrialists. It popularized technology, naval expansion, and military preparedness, and was well covered in the media.[104] Daniels and Benson rejected proposals to send observers to Europe, leaving the Navy in the dark about the success of the German submarine campaign.[105] Admiral William Sims charged after the war that in April 1917, only ten percent of the Navy's warships were fully manned; the rest lacked 43% of their seamen. Only a third of the ships were fully ready. Light antisubmarine ships were few in number, as if no one had noticed the U-boat factor that had been the focus of foreign policy for two years. The Navy's only warfighting plan, the "Black Plan" assumed the Royal Navy did not exist and that German battleships were moving freely about the Atlantic and the Caribbean and threatening the Panama Canal.[106][107] His most recent biographer concludes that, "it is true that Daniels had not prepared the navy for the war it would have to fight."[108]

Fighting a world war, 1917–18

President Wilson ordered the United States Marine Corps enlisted strength increased on March 26; and the United States Naval Academy class of 1917 graduated three months early on March 29 before America entered the war in April 1917. Retired officers were recalled to active duty at shore station billets freeing younger officers for sea duty. The Navy was given control of the Coast Guard and of the Naval Militia of 584 officers and 7,933 men who were assigned to coast patrol service and the Naval Reserve Flying Corps. The Navy took possession of all United States wireless (radio) stations and dismantled those in less useful locations to salvage equipment for military use.[109] The Navy's role was mostly limited to convoy escort and troop transport and laying the North Sea Mine Barrage.[110] The first United States military unit sent to Europe was the First Aeronautic Detachment of seven naval officers and 122 enlisted men who arrived in France on June 5, 1917 to form the Northern Bombing Group.[111] The United States Navy sent a battleship group to Scapa Flow to join with the British Grand Fleet, destroyers to Queenstown, Ireland and submarines to help guard convoys. Several regiments of Marines were also dispatched to France. The first victory for the Navy in the war occurred on November 17, 1917 when USS Fanning and USS Nicholson sank the German U-boat U-58.[112] During World War I, the Navy was the first branch of the United States armed forces to allow enlistment by women in a non-nursing capacity, as Yeoman (F).[113] The first woman to enlist in the U.S. Navy was Loretta Perfectus Walsh on March 17, 1917.[114]

The Navy's vast wartime expansion was overseen by civilian officials, especially Assistant Secretary Franklin D. Roosevelt. In peacetime, the Navy confined all munitions that lacked civilian uses, including warships, naval guns, and shells to Navy yards. The Navy yards expanded enormously, and subcontracted the shells and explosives to chemical companies like DuPont and Hercules. Items available on the civilian market, such as food and uniforms were always purchased from civilian contractors. Armor plate and airplanes were purchased on the market.

Inter-war entrenchment and expansion (1918–1941)

At the end of World War I, the United States Navy had almost 500,000 officers and enlisted men and women and in terms of personnel was the largest in the world.[3] Younger officers were enthusiastic about the potential of land-based naval aviation as well as the potential roles of aircraft carriers. Chief of Naval Operations Benson was not among them. He tried to abolish aviation in 1919 because he could not "conceive of any use the fleet will ever have for aviation." However Roosevelt listened to the visionaries and reversed Benson's decision.[115]

_and_USS_Somers_(DD-301)_underway_off_San_Diego%252C_in_1928_(NH_81279).jpg.webp)

After a short period of demobilization, the major naval nations of the globe began programmes for increasing the size and number of their capital ships. Wilson's plan for a world-leading set of capital ships led to a Japanese counter-programme, and a plan by the British to build sufficient ships to maintain a navy superior to either. American isolationist feeling and the economic concerns of the others led to the Washington Naval Conference of 1921. The outcome of the conference included the Washington Naval Treaty (also known as the Five-Power treaty), and limitations on the use of submarines. The Treaty prescribed a ratio of 5:5:3:1:1 for capital ships between treaty nations. The treaty recognized the U.S. Navy as being equal to the Royal Navy with 525,000 tons of capital ships and 135,000 tons of aircraft carriers, and the Japanese as the third power. Many older ships were scrapped by the five nations to meet the treaty limitations, and new building of capital ships limited.[116]

One consequence was to encourage the development of light cruisers and aircraft carriers. The United States's first carrier, a converted collier named USS Langley was commissioned in 1922, and soon joined by USS Lexington and USS Saratoga, which had been designed as battlecruisers until the treaty forbade it. Organizationally, the Bureau of Aeronautics was formed in 1921; naval aviators would become referred to as members of the United States Naval Air Corps.[117]

Army airman Billy Mitchell challenged the Navy by trying to demonstrate that warships could be destroyed by land-based bombers. He destroyed his career in 1925 by publicly attacking senior leaders in the Army and Navy for incompetence for their "almost treasonable administration of the national defense."[118]

Chief of Naval Operations William V. Pratt (1930-1933) agreed with President Hoovers's emphasis on disarmament and went along with postponement of new construction and cutting the fleet. Other naval officers disagreed sharply with Hoover's policies.[119][120]

President Franklin Roosevelt (1933-1945) had been in effect in civilian control of the Navy during World War I, knew many senior officers, and strongly supported naval expansion.[121] The Vinson-Trammell Act of 1934 set up a regular program of ship building and modernization to bring the Navy to the maximum size allowed by treaty. The Navy's preparation was helped along by another Navy assistant secretary turned president, Franklin D. Roosevelt.[122] The naval limitation treaties also applied to bases, but Congress only approved building seaplane bases on Wake Island, Midway Island and Dutch Harbor and rejected any additional funds for bases on Guam and the Philippines.[123] Navy ships were designed with greater endurance and range which allowed them to operate further from bases and between refits.[124]

The Navy had a presence in the Far East with a naval base in the US-owned Philippines and river gunboats in China on the Yangtze River. The gunboat USS Panay was bombed and machine-gunned by Japanese airplanes. Washington quickly accepted Japan's apologies and compensation.

African-Americans were enlisted during World War I, but this was halted in 1919 and they were mustered out of the Navy. Starting in the 1930s a few were recruited to serve as stewards in the officers mess. African-Americans were recruited in larger numbers only after Roosevelt insisted in 1942.[125]

The Naval Act of 1936 authorized the first new battleship since 1921, and USS North Carolina, was laid down in October 1937. The Second Vinson Act authorized a 20% increase in the size of the Navy, and in June 1940 the Two-Ocean Navy Act authorized an 11% expansion in the Navy. Chief of Naval Operations Harold Rainsford Stark asked for another 70% increase, amounting to about 200 additional ships, which was authorized by Congress in less than a month. In September 1940, the Destroyers for Bases Agreement gave Britain much-needed destroyers—of WWI vintage—in exchange for United States use of British bases.[126]

In 1941, the Atlantic Fleet was reactivated. The Navy's first shot in anger came on April 9, when the destroyer USS Niblack dropped depth charges on a U-boat detected while Niblack was rescuing survivors from a torpedoed Dutch freighter. In October, the destroyers Kearny and Reuben James were torpedoed, and Reuben James was lost.[127]

Submarines

Submarines were the "silent service"—in terms of operating characteristics and the closed-mouth preferences of the submariners. Strategists had, however, been looking into this new type of warship, influenced in large part by Germany's nearly successful U-boat campaign. As early as 1912, Lieutenant Chester Nimitz had argued for long-range submarines to accompany the fleet to scout the enemy's location. The new head of the Submarine Section in 1919 was Captain Thomas Hart, who argued that submarines could win the next war: "There is no quicker or more effective method of defeating Japan than the cutting of her sea communications."[128] However Hart was astonished to discover how backward American submarines were compared to captured German U-boats, and how unready they were for their mission.[129]

The public supported submarines for their coastal protection mission; they would presumably intercept enemy fleets approaching San Francisco or New York. The Navy realized it was a mission that isolationists in Congress would fund, but it was not actually serious. Old-line admirals said the mission of the subs ought to be as eyes of the battle fleet, and as assistants in battle. That was unfeasible since even on the surface submarines could not move faster than 20 knots, far slower than the 30 knot main warships. The young commanders were organized into a "Submarine Officers' Conference" in 1926.[130] They argued they were best suited for the commerce raiding that had been the forte of the U-boats. They therefore redesigned their new boats along German lines, and added the new requirement that they be capable of sailing alone for 7,500 miles on a 75-day mission. Unrestricted submarine warfare had led to war with Germany in 1917, and was still vigorously condemned both by public opinion and by treaties, including the London Treaty of 1930. Nevertheless, the submariners planned a role in unrestricted warfare against Japanese merchant ships, transports and oil tankers. The Navy kept its plans secret from civilians. It was an admiral, not President Roosevelt, who within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, ordered unrestricted warfare against any enemy ship anywhere in the Pacific.[131]

The submariners had won over Navy strategists, but their equipment was not yet capable of handling their secret mission. The challenge of designing appropriate new boats became a high priority by 1934, and was solved in 1936 as the first new long-range, all welded submarines were launched. Even better were the S-class Salmon class (launched in 1937), and its successors the T-class or Tambor submarines of 1939 and the Gato class of 1940. The new models cost about $5–6 million each. At 300 feet in length and 1500 tons, they were twice as big as the German U-boats, but still highly maneuverable. In only 35 seconds they could crash dive to 60 feet. The superb Mark 3 TDC Torpedo Data Computer (an analog computer) took data from periscope or sonar readings on the target's bearing, range and angle on the bow, and continuously set the course and proper gyroscope angle for a salvo of torpedoes until the moment of firing. Six forward tubes and 4 aft were ready for the 24 Mk-14 "fish" the subs carried. Cruising on the surface at 20 knots (using 4 diesel engines) or maneuvering underwater at 8-10 knots (using battery-powered electric motors) they could circle around slow-moving merchant ships. New steels and welding techniques strengthened the hull, enabling the subs to dive as deep as 400 feet in order to avoid depth charges. Expecting long cruises the 65 crewmen enjoyed good living conditions, complete with frozen steaks and air conditioning to handle the hot waters of the Pacific. The new subs could remain at sea for 75 days, and cover 10,000 miles, without resupply. The submariners thought they were ready—but they had two hidden flaws. The penny-pinching atmosphere of the 1930s produced hypercautious commanders and defective torpedoes. Both would have to be replaced in World War II.[132]

Worldwide expansion

World War II (1941–1945)

Command structure

After the disaster at Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt turned to the most aggressive sailor available, Admiral Ernest J. King (1878–1956). Experienced in big guns, aviation and submarines, King had a broad knowledge and a total dedication to victory. He was perhaps the most dominating admiral in American naval history; he was hated but obeyed, for he made all the decisions from his command post in the Washington, and avoided telling anyone.[133] The civilian Secretary of the Navy was a cipher whom King kept in the dark; that only changed when the Secretary died in 1944 and Roosevelt brought in his tough-minded aide James Forrestal.[134] Despite the decision of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Admiral William D. Leahy to concentrate first against Germany, King made the defeat of Japan his highest priority. For example, King insisted on fighting for Guadalcanal despite strong Army objections.[135] His main strike force was built around carriers based at Pearl Harbor under the command of Chester Nimitz.[136] Nimitz had one main battle fleet, with the same ships and sailors but two command systems that rotated every few months between Admiral Bull Halsey[137] and Admiral Raymond A. Spruance.[138] The Navy had a major advantage: it had broken the Japanese code.[139] It deduced that Hawaii was the target in June 1942, and that Yamamoto's fleet would strike at Midway Island. King only had four carriers in operation; he sent them all to Midway where in a miraculous few minutes they sank the Japanese carriers. This gave the Americans the advantage in firepower that grew rapidly as new American warships came on line much faster than Japan could build them. King paid special attention to submarines to use against the overextended Japanese logistics system. They were built for long-range missions in tropical waters, and set out to sink the freighters, troop transports and oil tankers that held the Japanese domains together.[140] The South West Pacific Area, based in Australia, was under the control of Army General Douglas MacArthur; King assigned him a fleet of his own under Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, without any big carriers.

Carrier warfare

On December 7, 1941, Japan's carriers launched the Attack on Pearl Harbor, sinking or disabling the entire battleship fleet. The stupendous defeat forced Admiral King to develop a new strategy based on carriers. Although the sunken battleships were raised, and many new ones were built, battleships played a secondary role in the war, limited chiefly to bombardment of islands scheduled for amphibious landings. The "Big Gun" club that had dominated the Navy since the Civil War lost its clout.[141]

The U.S. was helpless in the next six months as the Japanese swept through the Western Pacific and into the Indian Ocean, rolling up the Philippines as well as the main British base at Singapore.[142] After reeling from these defeats the Navy stabilized its lines in summer 1942.

_is_hit_by_a_torpedo_on_4_June_1942.jpg.webp)

At the start of the war, the United States and Japan were well matched in aircraft carriers, in terms of numbers and quality, but the Mitsubishi A6M Zero carrier fighter plane was superior in terms of range and maneuverability to its American counterpart, the F4F Wildcat. By reverse engineering a captured Zero, the American engineers identified its weaknesses, such as inadequate protection for the pilot and the fuel tanks, and built the Hellcat as a superior weapon system. In late 1943 the Grumman F6F Hellcats entered combat. Powered by the same 2,000 horsepower Pratt and Whitney 18-cylinder radial engine as used by the F4U Corsair already in service with the Marine Corps and the UK's allied Fleet Air Arm, the F6Fs were faster (at 400 mph) than the Zeros, quicker to climb (at 3,000 feet per minute), more nimble at high altitudes, better at diving, had more armor, more firepower (6 machine guns fired 120 bullets per second) than the Zero's two machine guns and pair of 20 mm autocannon, carried more ammunition, and used a gunsight designed for deflection shooting at an angle. Although the Hellcat was heavier and had a shorter range than the Zero, on the whole it proved a far superior weapon.[143] Japan's carrier and pilot losses at Midway crippled its offensive capability, but America's overwhelming offensive capability came from shipyards that increasingly out produced Japan's, from the refineries that produced high-octane gasoline, and from the training fields that produced much better trained pilots. In 1942 Japan commissioned 6 new carriers but lost 6; in 1943 it commissioned 3 and lost 1. The turning point came in 1944 when it added 8 and lost 13. At war's end Japan had 5 carriers tied up in port; all had been damaged, all lacked fuel and all lacked warplanes. Meanwhile, the US launched 13 small carriers in 1942 and one large one; and in 1943 added 15 large and 50 escort carriers, and more arrived in 1944 and 1945. The new American carriers were much better designed, with far more antiaircraft guns, and powerful radar.[144]

Both sides were overextended in the exhaustive sea, air and land battles for Guadalcanal. The Japanese were better at night combat (because the American destroyers had only trained for attacks on battleships).[145] However, the Japanese could not feed its soldiers so the Americans eventually won because of superior logistics.[146][147] The Navy built up its forces in 1942–43, and developed a strategy of "island-hopping, that is to skip over most of the heavily defended Japanese islands and instead go further on and select islands to seize for forward air bases.

In the Atlantic, the Allies waged a long battle with German submarines which was termed the Battle of the Atlantic. Navy aircraft flew from bases in Greenland and Iceland to hunt submarines, and hundreds of escort carriers and destroyer escorts were built which were specifically designed to protect merchant convoys.[148] In the Pacific, in an ironic twist, the U.S. submarines fought against Japanese shipping in a mirror image of the Atlantic, with German submarines hunting U.S. merchant ships. At the end of the war the U.S. had 260 submarines in commission. It had lost 52 submarines during the war, 36 in actions in the Pacific.[149] Submarines effectively destroyed the Japanese merchant fleet by January 1945 and choked off Japan's oil supply.[150]

In the summer of 1943, the U.S. began the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign to retake the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. After this success, the Americans went on to the Mariana and Palau Islands in summer 1944. Following their defeat at the Battle of Saipan, the Imperial Japanese Navy's Combined Fleet, with 5 aircraft carriers, sortied to attack the Navy's Fifth Fleet during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, which was the largest aircraft carrier battle in history.[151] The battle was so one-sided that it became known as the "Marianas turkey shoot"; the U.S. lost 130 aircraft and no ships while the Japanese lost 411 planes and 3 carriers. Following victory in the Marianas, the U.S. began the reconquest of the Philippines at Leyte in October 1944. The Japanese fleet sortied to attack the invasion fleet, resulting in the four-day Battle of Leyte Gulf, one of the largest naval battles in history.[152] The first kamikaze missions were flown during the battle, sinking USS St. Lo and damaging several other U.S. ships; these attacks were the most effective anti-ship weapon of the war.[153]

The Battle of Okinawa became the last major battle between U.S. and Japanese ground units. Okinawa was to become a staging area for the eventual invasion of Japan since it was just 350 miles (560 km) south of the Japanese mainland. Marines and soldiers landed unopposed on April 1, 1945, to begin an 82-day campaign which became the largest land-sea-air battle in history and was noted for the ferocity of the fighting and the high civilian casualties with over 150,000 Okinawans losing their lives. Japanese kamikaze pilots inflicted the largest loss of ships in U.S. naval history with the sinking of 36 and the damaging of another 243. Total U.S. casualties were over 12,500 dead and 38,000 wounded, while the Japanese lost over 110,000 men, making Okinawa one of the bloodiest battles in history.[154]

The fierce fighting on Okinawa is said to have played a part in President Truman's decision to use the atomic bomb and to forego an invasion of Japan. When the Japanese surrendered, a flotilla of 374 ships entered Tokyo Bay to witness the ceremony conducted on the battleship USS Missouri.[155] By the end of the war the US Navy had over 1200 warships, surpassing the size of the Royal Navy.[156]

Cold War (1945–1991)

The immediate postwar fate of the Navy was the scrapping and mothballing of ships on a large scale; by 1948 only 267 ships were active in the Navy.[156] In 1948 the Women's Armed Services Integration Act gave women permanent status in the Regular and Reserve forces of the Navy.[157]

Revolt of the Admirals

The military services were unified in 1947 over the strong objections of Navy Secretary James Forrestal. President Truman appointed him Secretary of Defense, but the two disagreed over budgets and Truman fired him in 1949 when Forrestal took the Navy's side in a public protest against White House policy known as the Revolt of the Admirals. A basic political problem was that the Secretary of Defense did not fully control the budgets of the three services. Each one worked with powerful Congressmen to enhance their budgets despite the White House determination to hold down spending. In 1948–49 the "Revolt of the Admirals" came when a number of retired and active-duty admirals publicly disagreed with President Truman and with his replacement for Forrestal Louis A. Johnson because they wanted less expensive strategic atomic bombs delivered by the Air Force. Forrestal had supported the Navy position and had obtained funding for an aircraft carrier from Congress. Truman fired Forrestal, and Johnson cancelled the carrier and announced plans to move Marine Corps aviation out of the Navy and into the Air Force. During Congressional hearings public opinion shifted strongly against the Navy. In the end the Navy kept Marine aviation and eventually got its carrier, but its revolting admirals were punished and it lost control over strategic bombing. The Truman administration essentially defeated the Revolt, and civilian control over the military was reaffirmed. Military budgets following the hearings prioritized the development of Air Force heavy bomber designs, accumulating a combat ready force of over 1,000 long-range strategic bombers capable of supporting nuclear mission scenarios.[158]

The Navy gradually developed a reputation for having the most highly developed technology of all the U.S. services. The 1950s saw the development of nuclear power for ships, under the leadership of Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the development of missiles and jet aircraft for Navy use and the construction of supercarriers. USS Enterprise was the world's first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and was followed by the Nimitz-class supercarriers. Ballistic missile submarines grew ever more deadly and quiet, culminating in the Ohio-class submarines.[159] Rickover had a strong base of support in Congress and in public opinion, and he forced nuclear power to be a high Navy priority, especially for submarines. Combined with missile technology, this gave the United States the assured second-strike capability that was the foundation of deterrence against the Soviet Union.[160]

Korean War and naval expansion

Tension with the Soviet Union and China came to a head in the Korean War, and it became clear that the peacetime Navy would have to be much larger than ever imagined. Fleets were assigned to geographic areas around the world, and ships were sent to hot spots as a standard part of the response to the periodic crises.[161] However, because the North Korean navy was not large, the Korean War featured few naval battles; the combatant navies served mostly as naval artillery for their in-country armies. A large amphibious landing at Inchon succeeded in driving the North Koreans back across the 38th parallel. The Battle of Chosin Reservoir ended with the evacuation of almost 105,000 UN troops from the port of Hungnam.[162]

The U.S. Navy's 1956 shipbuilding program was significant because it included authorization for the construction of eight submarines, the largest such order since World War II.[163] This FY-56 program included five nuclear-powered submarines – Triton, the guided missile submarine Halibut, the lead ship for the Skipjack class, and the final two Skate-class attack submarines, Sargo and Seadragon. It also included the three diesel-electric Barbel class, the last diesel-electric submarines to be built by the U.S. Navy.[164]

Vietnam War

An unlikely combination of Navy ships fought in the Vietnam War 1965–72; aircraft carriers offshore launched thousands of air strikes, while small gunboats of the "brown-water navy" patrolled the rivers. Despite the naval activity, new construction was curtailed by Presidents Johnson and Nixon to save money, and many of the carriers on Yankee Station dated from World War II. By 1978 the fleet had dwindled to 217 surface ships and 119 submarines.[165]

Soviet challenge

Meanwhile, the Soviet fleet had been growing, and outnumbered the U.S. fleet in every type except carriers, and the Navy calculated they probably would be defeated by the Soviet Navy in a major conflict.[166] This concern led the Reagan administration to set a goal for a 600-ship Navy, and by 1988 the fleet was at 588, although it declined again in subsequent years. The Iowa-class battleships Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, and Wisconsin were reactivated after 40 years in storage, modernized, and made showy appearances off the shores of Lebanon and elsewhere. In 1987 and 1988, the United States Navy conducted various combat operations in the Persian Gulf against Iran, most notably Operation Praying Mantis, the largest surface-air naval battle with US involvement since World War II.[167]

Post–Cold War (1991–present)

.jpg.webp)

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Navy fell apart, without sufficient personnel to man many of its ships or the money to maintain them—indeed, many of them were sold to foreign nations. This left the United States as the world's undisputed naval superpower. U.S. naval forces did undergo a decline in absolute terms but relative to the rest of the world, however, United States dwarfs other nations' naval power as evinced by its 11 aircraft supercarriers and their supporting battle groups. During the 1990s, the United States naval strategy was based on the overall military strategy of the United States which emphasized the ability of the United States to engage in two simultaneous limited wars along separate fronts.[168]

The ships of the Navy participated in a number of conflicts after the end of the Cold War. After diplomatic efforts failed, the Navy was instrumental in the opening phases of the 1991 Gulf War with Iraq; the ships of the navy launched hundreds of Tomahawk II cruise missiles and naval aircraft flew sorties from six carriers in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea. The battleships Missouri and Wisconsin fired their 16-inch guns for the first time since the Korean War on several targets in Kuwait in early February.[169] In 1999, hundreds of Navy and Marine Corps aircraft flew thousands of sorties from bases in Italy and carriers in the Adriatic against targets in Serbia and Kosovo to try to stop the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. After a 78-day campaign Serbia capitulated to NATO's demands.[170]

As a result of a large number of command officers being fired for failing to do their job properly, in 2012 the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) ordered a new method of selecting command officers across the Navy.[171]

In March 2007, the U.S. Navy reached its smallest fleet size, with 274 ships, since World War I. Since the end of the Cold War, the Navy has shifted its focus from preparations for large-scale war with the Soviet Union to special operations and strike missions in regional conflicts. The Navy participated in the Iraq War and is a major participant in the ongoing War on Terror, largely in this capacity. Development continues on new ships and weapons, including the Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carriers and the Littoral combat ships. One hundred and three U.S. Navy personnel died in the Iraq War.[172] U.S. Navy warships launched cruise missiles into military targets in Libya during Operation Odyssey Dawn to enforce a UN resolution.[173]

Former U.S. Navy admirals who head the U.S. Naval Institute have raised concerns about what they see as the ability to respond to "aggressive moves by Iran and China".[4][5] As part of the pivot to the Pacific, Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta said that the Navy would switch from a 50/50 split between the Pacific and the Atlantic to a 60/40 percent split that favored the Pacific, but the CNO, Admiral Jonathan Greenert, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, have said that this would not mean "a big influx of troops or ships in the Western Pacific".[174][175][176] This pivot is a continuation of the trend towards the Pacific that first saw the Cold War's focus against the Soviet Union with 60 percent of the American submarine fleet stationed in the Atlantic shift towards an even split between the coasts and then in 2006, 60 percent of the submarines stationed on the Pacific side to counter China. The pivot is not entirely about numbers as some of the most advanced platforms will now have a Pacific focus, where their capabilities are most needed.[177] However even a single incident can make a big dent in a fleet of modest size with global missions.[178]

On January 12, 2016, Iranian armed forces captured ten Navy personnel when their two boats entered Iranian territorial waters off the coast of Farsi Island in the Persian Gulf. They were released the next day following diplomatic discussions between the U.S. and Iran.

In mid-2017, two Navy ships, USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain, were involved in collisions with merchant ships during regular transits that resulted in fatalities.[179][180]

In 2020, the United States Navy was overtaken by the Chinese Navy in terms of raw number of ships.[6] The United States had previously held the title of largest navy since it surpassed the Royal Navy in 1943.[1]

See also

- Bibliography of early American naval history

- Board of Naval Commissioners

- General Board of the United States Navy

- History of homeland security in the United States

- List of United States Navy ships

- Naval History and Heritage Command - museums

- Seabees

- Ship Characteristics Board

- United States Coast Guard History and Heritage Sites

- United States Navy bureau system

- United States Navy systems commands

- List of bibliographies on American history

Citations

- 1 2 Crocker III, H. W. (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.

- ↑ Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Praeger, 1978).

- 1 2 Howarth 1999, p. 324

- 1 2 Stewart, Joshua (April 16, 2012). "SECNAV: Navy can meet mission with 300 ships". Navy Times. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- 1 2 Freedberg, Sydney J. Jr. (May 21, 2012). "Navy Strains To Handle Both China And Iran At Once". Aol Defense. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- 1 2 "China's vast fleet is tipping the balance against U.S. In the Pacific". Reuters.

- 1 2 "Establishment of the Navy, 13 October 1775". Naval History & Heritage Command. US Navy. Archived from the original on February 4, 1999. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ↑ Jonathan R. Dull, American Naval History, 1607–1865: Overcoming the Colonial Legacy (University of Nebraska Press; 2012)

- 1 2 Miller 1997, p. 15

- ↑ Howarth 1999, p. 6

- ↑ Westfield, Duane. Purdin, Bill (ed.). "The Birthplace of the American Navy". Marblehead Magazine. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 16

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 17

- ↑ Miller 1997, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 19

- ↑ Howarth 1999, p. 16

- ↑ Howarth 1999, p. 39

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 8

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 9

- ↑ Robert W. Love, Jr., History of the U.S. Navy (1992) vol 1 pp. 27–41

- ↑ "Alliance". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ↑ Miller 1997, pp. 33–35

- ↑ Howarth 1999, pp. 65–66

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 14

- ↑ "The First 10 Cutters". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ↑ "U.S. Coast Guard History Program". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ↑ Howarth 1999, pp. 49–50

- 1 2 Miller 1997, pp. 35–36

- 1 2 Sweetman 2002, p. 15

- 1 2 3 Sweetman 2002, p. 16

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 40

- ↑ Miller 1997, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 46

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 19

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 22

- ↑ Miller 1997, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 59

- ↑ David Stephen Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler (2004). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-1591143628.

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 58

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 23

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 65

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 26

- ↑ Sweetman 2002, p. 30

- ↑ Miller 1997, p. 68

- ↑ Howarth 1999, p. 109

- 1 2 Miller 1997, p. 72