The Lord Darling | |

|---|---|

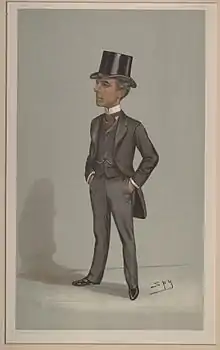

"Little Darling"

Darling as caricatured by Spy (Leslie Ward) in Vanity Fair, July 1897 | |

| 1st Baron Darling | |

| In office 1924–1936 | |

| Justice of the High Court | |

| In office 1897–1923 | |

| Member of Parliament for Deptford | |

| In office 1888–1897 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 December 1849 Abbey House, Colchester, UK |

| Died | 29 May 1936 Lymington, Hampshire, UK |

Charles John Darling, 1st Baron Darling, PC (6 December 1849 – 29 May 1936) was an English lawyer, politician and High Court judge.[1]

Early life and career

Darling was born in Abbey House in Colchester, the eldest son of Charles Darling and Sarah Frances (Tizard) Darling.[1] Of delicate health, he was educated privately. Under the patronage of his uncle William Menelaus, he was articled with a firm of solicitors in Birmingham, before entering the Inner Temple as a student in 1872. After reading in the chambers of the pleader John Welch, Darling was called to the bar in 1874. He then devilled for John Huddleston (later Baron Huddleston) and joined the Oxford circuit. Although he took silk in 1885 he was never prominent at the bar and practised almost entirely within his own circuit. He combined his legal career with journalism, and contributed to the St. James's Gazette, the Pall Mall Gazette, and the Saturday Review.

After unsuccessfully contesting Hackney South as a Conservative in 1885 and 1886, Darling was returned for Deptford in a by-election in 1888, defeating Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, and held the seat until his elevation to the bench in 1897.[1]

His time in the House of Commons was said to be undistinguished. He mainly spoke on legal issues and Irish Home Rule, and was said to never have entered the important House of Commons Smoking Room on grounds that he did not smoke.

In 1896, Darling was appointed commissioner of assize for the Oxford circuit. The Liberal opposition accused him of having vacated his seat by accepting an office of profit under the Crown, but Darling was able to point out that he accepted no payment.

Judicial career

Darling was appointed a Justice of the High Court in 1897, and received the customary knighthood. The appointment had been made at the recommendation of the Lord Chancellor Lord Halsbury, who was known to let political considerations influence his choice of judges, and was widely condemned as political. The Times commented that although he possessed "acute intellect and considerable literary power", he had given "no sign of legal eminence".

Assigned to the Queen's Bench Division, Darling presided over a number of important trials, including the Stinie Morrison case (1911),[2] that of "Chicago May",[3] and the trial for criminal libel of Noel Pemberton Billing MP (1918), brought by Maud Allan after Billing and Harold Sherwood Spencer had claimed there were 47,000 "sexual perverts" in high places who were controlled by the Germans. He also sat on the criminal appeals of Hawley Crippen and Roger Casement, both of which he dismissed.

He was known for his erudition and at times inappropriate wit, both on and off the bench, as well as for being impeccably dressed and wearing a silk top hat whilst riding to Court on a horse and accompanied by a liveried groom. He displayed his literary acuity in a book of essays Scintillae Juris.[4] The novelist and barrister F. C. Philips gave his opinion, 'I think that the wittiest book ever written by a legal luminary was one called "Scintillæ Juris" by Mr. Justice Darling, when he was a barrister on the Oxford Circuit. I understand that when he was raised to the Bench he stopped its circulation.'[5]

During the Billing trial one of the witnesses, Eileen Villiers-Stuart, claimed to have seen the mysterious "Black Book" in which the names of the "perverts" were listed, declared in court that Darling was one of them. She was later convicted of bigamy, and admitted that her testimony was invented.[6]

During the First World War, Lord Reading, the Lord Chief Justice, was frequently absent on diplomatic business. As the Senior Puisne Judge in the King's Bench Division, Darling deputized for him, and was sworn of the Privy Council in 1917 as a reward. In 1922, he was mooted as a stop-gap Lord Chief Justice until Sir Gordon Hewart could be appointed. Darling went so far as to write to Hewart asking for the office "even for ten minutes", but was passed over in favour of Mr Justice A. T. Lawrence. On hearing the news he was said to have remarked that he supposed he was not old enough (Darling being then 71 to Lawrence's age 77).

He retired from the bench in 1923, and was created Baron Darling, of Langham in the County of Essex on 12 January 1924.[7] In retirement he spoke in the Lords on legal issues and sat in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. He also sometimes sat in the King's Bench Division to deal with its arrears. He died at the Cottage Hospital, Lymington, Hampshire, on 29 May 1936 aged 86, and was succeeded as Baron Darling by his grandson, Robert Charles Henry Darling,[1] his only son having predeceased him.

Family

Darling married Mary Caroline Greathed (d. 1913) on 16 September 1885. She was the daughter of Major-General William Wilberforce Harris Greathed and Alice Clive. They had one son and two daughters.

Arms

|

|

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Darling, Charles John, first Baron Darling". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32714. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Moulton, H. Fletcher, ed. (1922). Trial of Steine Morrison. Notable British trials. London: W. Hodge & Co.

- ↑ Sharpe, May Churchill (1928). Chicago May: Her Story. New York: Macaulay Co.

- ↑ Darling, Charles J. (1877). Scintillae Juris (2nd ed.). London: Davis & Son.

- ↑ Philips, F. C. (1914). My Varied Life. London: E. Nash. p. 271.

- ↑ Andrew, Christopher, Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community, (1985)

- ↑ "No. 32898". The London Gazette. 15 January 1924. p. 459.

- ↑ Burke's Peerage. 1959.

- Peter James Rainton and Peerage. com.

- Smith, Derek Walter, "The Life of Charles Darling", Cassell & Co, London (1938).

- Simpson, A.W.B., "A Biographical Dictionary of the Common Law", Butterworths, London, 1984, p 143.

- Hoare, Philip, "Wilde's Last Stand", Duckworth Overlook, London 1997, 2011, pp 112–181, 217-218 (concerning the Pemberton Billing trial).

- Gilbert, Michael (ed), "The Oxford Book of Legal Anecdotes", OUP, Oxford, 1986, pp 91–97.