| Redfern Park | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Redfern Park, pictured in 2014 | |

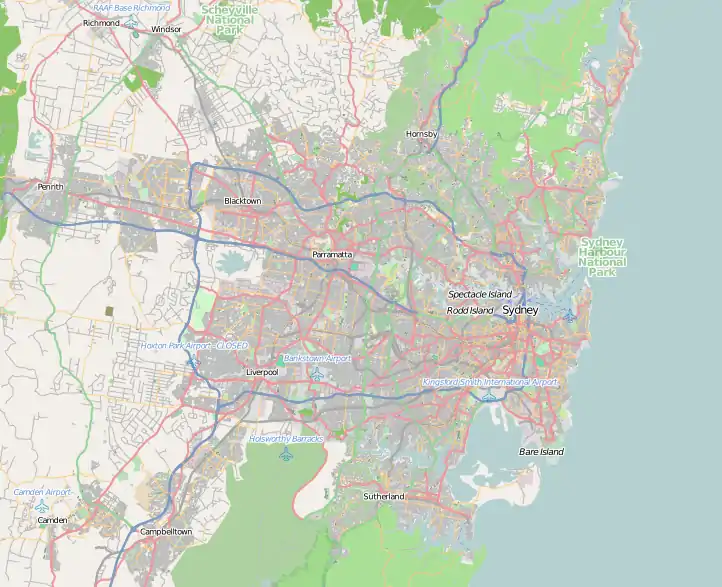

Location in greater Sydney | |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Elizabeth, Redfern, Chalmers, and Phillip Streets, Redfern, Sydney, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°53′37″S 151°12′22″E / 33.8935°S 151.2061°E |

| Created | 10 November 1885 |

| Operated by | City of Sydney |

| Open | 24 hours |

| Status | Open all year |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Redfern Park and Oval |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 21 September 2018 |

| Reference no. | 2016 |

| Type | Place of significance |

| Category | Aboriginal |

Redfern Park is a heritage-listed park at Elizabeth, Redfern, Chalmers and Phillip streets, Redfern, Sydney, Australia. It was designed by Charles O'Neill. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 21 September 2018.[1]

History

Traditional owners

The Gadigal People of the Eora Nation are recognised as the traditional custodians of the land on which Redfern Park and Oval are now located, as well as the greater Redfern area. The Gadigal have a rich culture and strong community values.[1][2]: 1 The area now forming Redfern Park has always been a significant place for Aboriginal people. This part of Sydney was originally park of a diverse wetland that connected to the Tank Stream and an important meeting place.[3][1]

The British invasion brought smallpox, which had a catastrophic impact on the Aboriginal clans of the Sydney area, and the colony itself soon spread to the Redfern area, partly in pursuit of clean fresh water following pollution of the Tank Stream. Many Aboriginal people moved to La Perouse and elsewhere, and began to become prominent in city life again from the 1930s, when working class suburbs like Pyrmont, Balmain, Rozelle, Glebe and Redfern became central places for Aboriginal families to like, where housing was relatively cheap and there was plenty of work in nearby factories. Many travelled from northern and western NSW for the increased work opportunities after the outbreak of World War 2. Changes in government legislation in the 1960s provided freedom of movement enabling more Aboriginal people to choose to live in Sydney.[1]

Redfern (suburb)

Redfern's natural landscape was defined by sand hills and swamps. The Carrahdigang, more widely known as the Cadigal people, valued the area for its abundant supply of food.[1][4]: 5 The name originates from an early land grant to William Redfern in 1817. It was previously known as Roberts Farm and Boxley's Swamp.[4]: 5 Redfern (1774?-1833) was a surgeon's mate in the Royal Navy and was aboard HMS Standard when its crew took part in the revolt in 1797 known as the Mutiny of the Nore. Because he had advised the men to be more united, he was included among leaders who were court-martialled. Although sentenced to death, he was reprieved because of his youth and in 1801 arrived in Sydney as a convict. He served on Norfolk Island as an assistant surgeon. In 1803 he was pardoned, but remained on the island until 1808, when he returned to Sydney and was appointed assistant surgeon after being examined in medicine and surgery by Surgeons Jamison, Harris and Bohan.[1][4]: 5

In 1816 he took charge of the new Sydney Hospital, and maintained a private practice. In 1814 he reported on conditions on convict transport ships and his recommendation that all have a surgeon on board whose duties were to superintend the health of convicts was put into practice.[1][4]: 5

Redfern resigned from Government service in 1819 when not appointed to succeed D'Arcy Wentworth as principal surgeon. Despite his valuable service, many were contemptuous of him as he was an emancipist, although he had the friendship of Governor Macquarie. In 1818 Redfern received a grant of 526 hectares (1,300 acres) in Airds and later received more land in the area and by his death in 1823 he owned, by grant and purchase, over 9,308 hectares (23,000 acres) in NSW.[1][4]: 5

In 1817 he had been granted 40 hectares (100 acres) in the area of the present suburb of Redfern. The boundaries were approximately the present-day Cleveland, Regent, Redfern and Elizabeth Streets. The commodious home Redfern built on his land was considered to be a country house, surrounded by flower and kitchen gardens. His neighbours were John Baptist (at the 16-hectare (40-acre) Darling Nursery in today's Chippendale) and Captain Cleveland, an officer of the 73rd regiment, remembered by today's street of that name, and before its demolition, by Cleveland House, his home.[1][5]: 219–220

The passing of the Sydney Slaughterhouses Act in 1849 brought other businesses to the district. This act banned abattoirs and noxious trades from the city. Tanners, wool scourers and wool-washers, fellmongers, boiling down works and abattoirs had ten years to move their businesses outside city boundaries. Many of the trades moved to Redfern and Waterloo - attracted by the water. The sand hills still existed but by the late 1850s Redfern was a flourishing suburb housing 6,500 people.[1][4][5]: 219–220

The Municipalities Act of 1858 gave districts the option of municipal incorporation. Public meetings were held and after a flurry of petitions Redfern Municipality was proclaimed on 11 August 1859, the fourth in Sydney to be formed under the Act. Redfern Town Hall opened in 1870 and the Albert Cricket Ground in 1864. Redfern Post Office came in 1882.[1][4][5]: 219–220

The majority of houses in Redfern in the 1850s were of timber. From the 1850s market gardeners congregated in Alexandria south of McEvoy Street, around Shea's Creek and Bourke Road.[1][4][5]: 219–220

Construction of Redfern Park

Redfern Park remained swamp land while residential and industrial Redfern was built up around it, and it became known as Boxley's Lagoon and seen as a nuisance and a waste land. In 1885 South Sydney Council resumed five hectares (twelve acres) of the swamp for the park construction. Redfern Park was gazetted for the purpose of public recreation on 10 November 1885 and named as "Redfern Park" on 20 November 1885. South Sydney Council was appointed Trustee of the park under the Public Parks Act on 10 December 1885. Council prepared by-laws for the park in 1887 and installed a caretaker in 1888.< The park was styled as late Victorian Pleasure Gardens with Botanical Plantings and Landscape Design.[1][2]: 7 [6][7]: 3

Around 1886 planting began using tree saplings supplied by the Royal Botanic Gardens including Moreton Bay figs, deciduous figs, and Canary Island palms. The plantings used in the park reflect the preferences or botanical palate of the successive directors of the Botanic Gardens with Charles Moore (director 1848-1896) favouring Port Jackson and Moreton Bay figs and Joseph T. Maiden (director 1896-1924) deciduous figs and Canary Island pines.[1][2]: 8 [7]: 3–6

The park's layout was designed by the civil engineer Charles O'Neill in 1888. This design split the park into a southern section for sporting activities and a northern half comprising a formal landscaped garden for passive recreation which included extensive specimen plantings, lawns, flower gardens, seating, shaded walkways across the park and around the perimeter, decorative gates, and the Baptist fountain in the centre. A raised bandstand was located in the centre of the entire park.[1][7]: 4

Prominent local resident John Baptist Jr., of Portuguese background, donated the fountain and several urns for installation in the new landscaped park in 1889-1890. Baptist's father, John Baptist (Sr.) arrived in Sydney as a free man in 1829. He opened a nursery in Redfern to the east of what became Redfern Park (in what is now the Marriot Street Reserve area). The nursery originally focussed on vegetables but later expanded to include ornamental plants. In time, his nursery grew to comprise most of East Redfern. The Baptist fountain is extant (and has recently been restored) while the urns were removed in 1965. The cast iron fountain, which features a bronze finish, was manufactured in Coalbrookdale, England and imported to Australia as a kit which was then constructed on site. A number of these fountains were imported at this time. Today only a few survive: there is one at Forbes, NSW; one in the botanical gardens in Adelaide, SA; and another partial or incomplete one in the Fitzroy Gardens in Melbourne, Victoria. These remaining examples are slightly different designs, with the Redfern example with its "boy and serpent" motif being individual.[1][2]: 16 [7]: 4–5 [8]

While the park was under construction, the citizens of Redfern put together a subscription to erect sandstone gates at the northern entrance. This demonstrates the nature of the local civic pride that had led to the construction of the park. In 1891 the Redfern Street gates, which comprised two white painted sandstone piers supporting decorative wrought iron gates featuring a prominent Waratah motif, were installed.[1]

Redfern Park was officially opened in 1890. By the time it was finished it was a typical Victorian "pleasure ground" incorporating ornamental gardens, exotic plantings, cricket wickets and oval, bowling green, bandstand, and sporting pavilions. As such, from the beginning this park incorporated a mixture of pleasure and sporting facilities.[1][6][7]: 1 [8]

Operation of Redfern Park and Oval

Soon after construction of the park had begun, South Sydney Council was inundated with requests from local sporting clubs (rugby union, cricket, etc.) to use the oval. The park was initially designed with a cricket oval and wickets (1887-1890) and a bowling green and sporting activities may have commenced as early as 1886. In the decades following the opening of the oval it was used for rugby union during the winter and cricket during the summer. Rugby Union was first played at the park in May 1888. To further the use of the oval for cricket purposes a cricket pavilion, donated by the Redfern (South Sydney) Mayor, was opened in 1892.[1][7]: 3–5

From the early decades of the twentieth century sporting usage began to dominate at Redfern Park with the sporting facilities being used for tennis, rugby league, cricket, baseball, boxing, and many other sports. By 1909 the oval had been found to be too small for cricket and the Council moved to increase the size of the sports area of the park and enclose it within a seven foot fence. This likely had the unfortunate effect of separating "Redfern Park" into two distinct areas: a park and oval.[1][7]: 7–8

During the early twentieth century Rugby League became an increasing popular sport in the local area (and Sydney). The NSW Rugby Football League competition was formed on 17 January 1908 with South Sydney being one of the nine founding clubs. In 1911 Redfern Oval was first leased to the NSW Rugby Football League for the majority of the season beginning a regular arrangement. The oval may also have been used as a training venue by the South Sydney Rabbitohs from this time. The story that the "Rabbitohs" are named after the rabbit hawkers who plied their trade around Redfern Park during the early twentieth century (or was it the 1890s depression) suggests an early connection between the club and Redfern Oval.[1][7]: 8

Following the horror and loss of life of WWI many communities across Australia chose to honour and remember their local soldiers through living or static memorials. The Redfern community chose to erect a large sandstone/marble/granite memorial with statues to commemorate its dead. To fund its construction a large carnival (or several) were held in Redfern Park after the war. These efforts were successful and the extant WWI war memorial was constructed in the northwest corner of the park in 1919-1920.[1][6][7]: 8

Throughout the inter-war period sports became more popular among the local community (and the local population became more working class) the supporting facilities at Redfern Oval continued to be improved. By the 1930s cricket and rugby league continued to thrive, but bowling was losing popularity, and in 1934 the bowling club was asked to leave so the greens could be converted into tennis courts (1934-1935). In contrast, the ornamental gardens or pleasure grounds of Redfern Park were allowed to deteriorate until a restoration and clean-up program began in 1936-7. This program may have included the planting of more trees in the park, including the extant axial rows of palms. Further maintenance works were carried out during the 1943-1944 which included the proposed construction of a children's playground, which was not built until 1946.[1][7]: 9–11, 14

Following the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1942 during WWII zig-zag air raid trenches were installed on the east and west sides of the park. These were filled in after the war. Following the war a Canon Monument was installed in the park . There is no known connection between Redfern Park and this canon, nor with local servicemen, etc.[1][2]: 19 [7]: 10

In 1946 the South Sydney Rugby League Club approached Redfern Council about making Redfern Oval their home ground if suitable improvements were carried out. Construction works to upgrade the oval, including the upgrading of the oval surface, the construction of new embankments and facilities, and the remodelling of the original pavilion to function as a larger grandstand, commenced the following year. This work was completed in April 1948 in time for the Rabbitohs to commence matches at the Oval in this year's competition. The upgrade of Redfern Oval at this time resulted in the removal of the bandstand and mound located in the centre of "Redfern Park". Prior to this the bandstand had been used for Sunday performances in the park by local bands.[1][7]: 12–13

With the scant post-war resources of Council going towards the upgrading of Redfern Oval, the ornamental gardens of Redfern Park were once again neglected from the later 1940s to the 1970s. Throughout this period several of the ornamental features of the park were removed including the boundary walkways, and stone columns and pedestals with cast iron urns (1965) that had been donated by John Baptist. However, general maintenance continued and in 1963-65 the Baptist fountain was restored. In 1974 park beautification works involved the construction of five large raised sandstone garden beds around the Baptist fountain and from 1975 into the 1980s the asphalt paths were replaced with decorative interlocking paving. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s vandalism and theft was a continual problem, which required security (lighting) upgrades on several occasions, and the repair of the war memorial in 1973 and the 1980s.[1][7]: 15–16

Throughout its history, Redfern Park has seen many diverse uses in accordance with its value as an outdoor park within an otherwise heavily urbanised (and at times industrial) area. Historic community uses of the park have included outdoor films (talkies), Christmas Carols, and community, religious, and political meetings. These community uses of the park continue into the present. In the recent past the park has hosted community events including: the Redfern/Waterloo Festival, the Yabun Festival / Survival Day events, Music in the Park concerts, Carols in the Park, Anzac Day Memorial Services, and Citizenship Ceremonies.[1]

In 2007 Redfern Park and Oval was the subject of a major redevelopment project by the City of Sydney that aimed to renew the open-area nature of the park and update the sporting facilities so that the South Sydney Rabbitohs could continue to use the oval as a training facility. This project revitalised the park and oval and reintegrated these two public spaces more in accordance with the original design for the park. Today the park is considered to be one of the most beautiful in inner Sydney and an important green oasis in urban Redfern. Its beauty stems from the retention of its Victorian character and its mix of fine mature trees, expansive lawns, artistic features, and historic monuments. The success of the park's redevelopment project was recognised internationally in 2014 when it received a prestigious Green Flag Award marking it as one of the top parks in the world for recreation and relaxation.[1][6]

Development of the Redfern aboriginal community

Many Aboriginal people had survived in the Sydney area during the later nineteenth century by living outside of or on the fringes of European settlement. This was despite the efforts of the Aborigines Protection Board to confine Aboriginal settlement to various missions and reserves from the 1890s onwards. The 1930s depression and the efforts of the Aborigines Protection Board to disenfranchise and assimilate Aboriginal people (gain control of their lives) led many people to leave country areas and migrate to the city. The industries based in Redfern provided employment opportunities for these Aboriginal people leading to a small community forming during the 1930s.[1]

As the Aboriginal Redfern community grew from the 1930s-1940s onward Redfern Park became a meeting place for this community - it was a central public place in Redfern and close to many other important Aboriginal services and housing. The park became an important place where the Redfern community could meet and socialise with family groups from the country (the country mobs), as well as meet new arrivals from the country as it was close to Redfern station (the HUB) and everybody could find the park and oval due to their support of the South Sydney Rabbitohs (they knew where Redfern Oval was because of the televised football matches).[1][9]

Redfern Park became known as a comfortable place, and became part of the local community's sense of identity. The park was the only open, green space like this in Redfern. All the other "comfortable places" for Aboriginal people were houses. These comfortable places were increasingly important over time to the community and their sense of identity (and ownership) as they began the revolution in rights and self-determination in the 1960s and 1970s. The sense of identity and ownership of the local community was also important for newcomers as it helped them become part of the larger community and helped them find their own sense of identity, and also helped them to establish their own connections and find their own family and "mob". The sense of identity and ownership the Redfern Aboriginal community had for the Redfern area linked to many important landmarks and community or comfortable places that were, or became, part of the movement. These included the Block, the Redfern Medical Services, the Redfern Legal Services, Koori Radio, Redfern Park, and Redfern Oval.[1]

Redfern Oval, because it was a place where the Rabbitohs and All-Blacks played, was an exciting place for community members to visit due to the large number of Aboriginal players that played in both teams. Community members showed these places with pride to new mob and visiting friends and family, as a way of showing what they had achieved. It must be remembered that all this was achieved in the face of racist policies by the local police force and their persecution of the local community (and local and state government) (Pamela Young).[1]

Aboriginal involvement in Rugby League appears to have developed in the South Sydney region throughout the 1930s and 1940s. This was first in the "junior" leagues of the South Sydney district, which comprised the competition below the elite first grade inter-district competition in Sydney (so district wide). During this time there were All Aboriginal or "All Black" teams from both Redfern and La Perouse playing in the junior competition. They were formed in response to discrimination that prevented Aboriginal players from being selected in the established teams. The first All Black team appears to have been from La Perouse and played in the 1935 and 1938-1942 competitions.[1][10]: 35–36

The Redfern All Blacks were established in 1944 as a result of dances held at Redfern Town Hall held to raise funds for the court defence of the legal rights of repatriated Aboriginal servicemen if necessary. These funds were never required for this purpose and, instead, they were used to establish a football club to ease the boredom of slum life for Aboriginal men who had moved to the city from the bush. The club initially used Kensington Oval for training and organised to join the South Sydney junior league.[10]: 36 The team became increasingly popular and was able to attract many talented players including Charles "Chicka" Madden, Michael and Tony Mundine, Babs Vincent, Eric "Nugget" Mumbler, and Merv "Boomanulla" Williams. These players increasingly became role models and legends for young Aboriginal men in Redfern. The team also provided a place where new arrivals could find acceptance in the community and adjust to city life. The club increasingly offered a welcoming and inclusive place which gave members and supporters purpose, a sense of community, and a positive sense of identity and pride.[1][7]: 7–8

Throughout the later 1940s they competed in the local league alongside another Aboriginal team, the La Perouse Warriors (now United). During this time both teams trained and played at Redfern Oval, as well as other local venues such as Alexandria Oval. The RAB became increasingly popular during this time with two matches at Redfern Oval in 1950 against Fernleigh, one a round game and the other the grand final, drawing 8,000 and 15,000 spectators respectively. The club missed several seasons during the 1950s and early 1960s including 1953-1954 and 1957-1961. These hiatuses were likely due to the availability of agricultural versus factory work during these periods. The club again dropped out of the competition in the mid-1960s before it was resurrected in 1969 through financial assistance for the National Aboriginal Sports Foundation. This funding hoped to allow the club to serve social functions including helping integrate new arrivals to the city and providing management skill training for those involved in the running of the club.[1][10]: 37–38

After their reformation the club continued to play a prominent role in the community and was a major organisation during the self-determination and rights movement during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1971 the Redfern All Blacks were one of the seven founding teams of the Koori Knockout and they have continued to field teams in the competition to the present. The Koori Knockout was established to provide a stage where the many talented Aboriginal players, who were being overlooked by talent scouts, could display their skills. It also had an important family and community focus and was linked in with the political activism underway in Redfern at the time. The All Blacks have been very successful in this competition, winning the title on 10-12 occasions, which has resulted in the Knockout being held at Redfern Oval at least four times.[11][1][6]

Throughout its existence the Redfern All Blacks has been an important and empowering organisation for local young Aboriginal men. It has also played an important part in starting the Rugby League careers of many Aboriginal players who rose through the local competition to join the South Sydney Rabbitohs. Over time the club has continually expanded and now fields teams in men's, women's, and junior competitions. The club may be an importance force in the history and development of women's rugby league.[1]

It is unclear to what extent Redfern Oval was considered historically to be the home ground of the Redfern All Blacks. Today Redfern Oval is considered to be their home ground, but they may train at Alexandria Oval. When Redfern Oval was the home ground of the Rabbitohs (1946-1988) there were regular matches of the South Sydney juniors league at the ground, most often the finals each year. In this manner, the oval was a stage for more memorable matches throughout this period. However, nearly all the RAB players also supported the Rabbitohs so they still had a strong connection with the oval in this respect. It is likely RAB's connection to this oval has grown with time at it has become more available for use by the club.[1]

Rugby League: The South Sydney Rabbitohs

Redfern Oval became the home ground of the South Sydney Rabbitohs from the 1948 season of the NSW Rugby League competition. This was their first home ground. Improvements were continually made to the oval during the 1950s to provide better facilities for the spectators and players. This resulted in the slow removal of the other sporting facilities such as the tennis courts in 1958. Radio facilities were also likely provided early on so games could be broadcast. By the mid-1950s the oval needed a new grandstand. Consequently, the Reg Cope Grandstand was constructed between 1957 and 1959 along with other support facilities. This stand was named after Norman Reginald Cope a city alderman between 1950 and 1960.[1][7]: 13, 15

Further upgrade works to Redfern Oval were carried out in the 1970s. In 1977 as part of a state government project to provide local employment and upgrade community facilities the earthen banks of the oval were upgraded and fencing installed around the oval. The street frontages along Phillip, Elizabeth, and Chalmers streets were also landscaped and beautified with colourful shrubs and trees.[1][7]: 16

Between 1948 and 1987 the South Sydney Rabbitohs used Redfern Oval as their home ground before moving to Sydney Football Stadium in 1988. During this time Rabbitohs supporters referred to the oval as "The Holy Land". From 1988 the Rabbitohs used the oval as a training ground with occasional pre-season or exhibition matches.[1]

In 1999 when the Rabbitohs were expelled from the new 14 team NRL structure a massive march of 40,000 people was held that began at Redfern Oval and proceeded to Sydney Town Hall to protest against the decision.[1]

Between 2007 and 2009 the City of Sydney redeveloped Redfern Oval to update its facilities to permit the Rabbitohs to resume their usage of the oval as a training ground from 2009. This involved the removal of the Reg Cope Grandstand and levelling of the site. Since 2009 the Rabbitohs have held an annual pre-season match called "Return to Redfern" at Redfern Oval.[1]

The Long March of Freedom, Justice, and Hope, 1988

Redfern Park appears to have been a big meeting place for political activities during the 1960s and 1970s. This was specifically on Saturday nights when the community would gather to drink, play football, or to continue the traditional practices of meeting outside. It is possible that Redfern Oval was where plans for self-determination were originally discussed. This includes the early ideas for what became the Aboriginal Medical Service and Aboriginal Legal Service.[1][7]: 7–8

It is likely that Redfern Park and Oval's importance as a meeting place for the local and increasingly revolutionary Aboriginal Redfern Community led to it being associated with two of the most important events in Aboriginal history over the last thirty-forty years. In this manner this place has played an important part in the quest of Aboriginal people for recognition, justice, and equality in Australian society. These events have also led this place to becoming important in the efforts towards reconciliation between Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Australia which continue to this day.[1]

Many Aboriginal Australians felt insulted by the effort put into organising the 1988 Bicentennial festivities by the Federal and State Governments, especially when they faced such discrimination and social problems that required urgent attention and funding. They also felt that the arrival of the First Fleet was not something that should be celebrated, 'it wasn't decent', and that doing so was basically "a slap in the face" to Aboriginal people. They felt that the "death" of the Aboriginal "First Nations" of Australia triggered by the arrival of the First Fleet was an event to be mourned, not celebrated by the 'largest birthday party in Australia's history' and they were not going to let White Australia forget. Anger over these issues led many Aboriginal Activists across the country to plan a protest against these events.[1][12]

The inspiration for the Long March of Freedom, Justice, and Hope has its beginnings in the 150 year centenary celebration of the arrival of the First Fleet in 1938. On the eve of the planned celebrations, William Cooper challenged white Australians to recognise that "Australia Day" for black Australians was a "Day of Mourning" that commenced 150 years of invasion, dispossession, and exploitation. Aboriginal Australians continued or reaffirm this challenge over the following decades.[13][1]

Bob Hawke's Labor Government assumed power in 1983 and the new Prime Minister promised that he would "deliver national, uniform, land rights legislation" to the strong and growing Aboriginal Land Rights Movement. However, a severe backlash by mining and pastoral interest and elements of the Australian Labor Party caused the Hawke government to water down these promises and retreat from his commitments. Many Aboriginal people were outraged, particularly the National Federation of Land Councils and the National Aboriginal Conference, who had been involved in the government talks. This anger and frustration was also channelled into peaceful protests around the 1988 bicentennial celebrations.[14][1][15]: 493 [16]: 79

The 1988 bi-centenary celebrations were seen by Aboriginal activists as a prime opportunity to further their cause and highlight the appalling human rights record of White Australia. A large grassroots campaign was undertaken to mobilise Aboriginal communities across Australia and organise a protest that would draw mass media attention and highlight their message "White Australia has a Black History". In the lead-up to the bi-centenary 1988 was again christened as a "Year of Mourning" which was a sharp contrast to the National Program of events and celebrations organised by the state and federal governments to honour the White History of Australia.[1][12]

The idea for the march came from the Reverend Charles Harris who was inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1963 march on Washington and his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. The Native American 1978 Longest Walk march on Washington was another influence for the organisers. The march was organised by the Freedom Justice Hope Committee whose board comprised Judith Chester (1950-2010), Kevin Cook (1939-2015), Reverend Charlie Harris, Linda Burney (1957-), Chris Kirkbright, and Karen Flick, and many other people also contributed. Kevin Cook had created a strong network through his development of Tranby Indigenous Education and Training centre and his political and union activities allowed the committee to spread the message about the protest and gather support. Tranby became a hub for participants of the protest from outside the city and state in the days leading up to 1988 Australia/Invasion day.[1][12]

In the weeks and months leading up to the march convoys started from Aboriginal communities across the country heading for Sydney. These convoys often began as a group of buses, perhaps with some additional car loads of people, but as they travelled they grew in size as others joined. Camping spots were organised for each convoy along their journey (with local Aboriginal groups) and often convoys would have cooking teams that travelled ahead to set up camp for the arrival of the main group. As groups met up on their way to Sydney many impromptu meetings were held, including one large one at Mildura between the Darwin and Perth mobs.[1][12]

The travelling convoys wished to make a great scene upon their arrival in Sydney. Many groups had stayed at Mittagong the night before. On the day of their planned arrival in Sydney the convoys formed up along the Hume Highway. Once together, this large convoy entered Sydney, with a police escort of one car, receiving displays of support through different areas of the city, before heading to La Perouse which had been designated as the headquarters of the protest in the lead up to Invasion/Australia Day. The meeting up of the convoys with the "Sydney Mob" and other supporters was a joyous, emotional, and festive occasion remembered with great fondness by the protest participants.[1][12]

Over the next few days a great meeting was held between the protest participants to organise the march and other protests and their aims. It seems that prior to this meeting the route or location of the march had not been agreed upon by the protest participants, although the organisation committee may have developed some options for consideration. Two views regarding the march developed during the meeting: one that is should proceed from Redfern Park/Oval through the city streets to Hyde Park where a series of speeches and rallies would be held (Reverend Harris Mob) and the other that the march or protest should proceed to or be held at Lady Macquarie's chair overlooking the re-enactment celebrations. Many people felt that Aboriginal Australia needed a visible presence at the "Celebration of the Nation" festivities and re-enactment of the arrival of the First Fleet to protest against these activities. During the meeting protestors were already protesting along the shores of La Perouse against the re-enactments staged to celebrate the arrival of the First Fleet into Botany Bay. Ultimately, it appears that marchers were organised to participate in marches along both options with the smaller march to Lady Macquarie's Chair organised for earlier in the day and the larger march to Hyde Park later from mid-morning.[1][12]

On Australia/Invasion Day 1988, the protestors began to gather at Redfern Park from 10am. By 11am when the march was scheduled to begin, around 20,000 Aboriginal Australians from across the country had gathered along with non-Indigenous supporters. From Redfern Park the march progressed along both Chalmers and Elizabeth Streets and then stopped first at Belmore Park where a second group of mainly non-Indigenous supporters awaited their arrival. Many participants remember this as a key moment. The stone railway bridge over Eddy Avenue prevented the marchers from seeing or hearing the crowd in Belmont Park, which meant that when they arrived at the end of the Eddy Avenue tunnel they were suddenly confronted with a huge cheer from the gathered supporters. From Belmore Park the marchers continued to Hyde Park with the march growing along the route, to over 30,000 or 40,000 people depending on reports. At Hyde Park further speeches and events were held including a speech by the Aboriginal activist Gary Foley. This march was thought at the time to have been the largest Aboriginal gathering ever and was the largest protest march in Sydney since the Vietnam moratorium.[1][12]

The march was carried out peacefully and respectfully and was a spectacular achievement of organisation and management. The committee arranged stewards to manage the march as it progressed. There was a strict ban on alcohol on the day and people joined together to ensure this ban was kept so the police could not cause them any trouble. The success of the march drew attention from across the world and brought Indigenous issues to the forefront of the national consciousness. Today the march is still remembered as a day of hope and empowerment and its success still brings pride to the Aboriginal people and communities who participated.[1][12]

Ultimately, this march was an important protest and statement of survival for Aboriginal Australians. It was a demonstration or expression of Black identity and solidarity, and highlighted the plight of Aboriginal Australians in contemporary Australian society, especially the startling contrast between the third-world living conditions faced by many Aboriginal Australians and the lavish amounts of money (A$200 million ) spent by the Federal Government on the enormous pomp and ceremony celebrating the British invasion of Australia.[1][12]

The success of the march led to important steps forward in Aboriginal rights, issues, recognition, and reconciliation during the late 1980s and early 1990s changing white and black Australia forever. In the following years numerous peak Indigenous organisations were established including the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in 1990 and the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation in 1991. The protest also arguably inspired a new generation of Indigenous leaders and created new attitudes towards the celebration of Australia Day and the realisation of what this event means for Aboriginal people. Most importantly, the protest triggered mass public debate about these issues with Indigenous people holding a prominent part in the wider dialogue. These debates included discussions about the very concept of Australian History and the position of Aboriginal people and their voices within it and contemporary Australian society.[1][12]

88 Documentary: One of the interviewees describes the march as being the first step forward towards reconciliation.[1]

Prime Minister Paul Keating's Redfern Speech, 1992

Paul Keating became Prime Minister in December 1991. Keating had a long-standing desire to deliver justice to Aboriginal Australians.[15]: 205 [17] He had supported the 1967 referendum, Northern Territory land rights legislation, and mining companies showing respect for traditional owners. While treasurer during the 1980s he also supported budget programs that extended opportunity, support, and dignity to Aboriginal Australians. Following the 1988 Long March, he supported the establishment of ATSIC and the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation. Despite these modest achievements by the Hawke Government he considered the government's failure to pursue national land rights legislation in the mid-1980s as a costly mistake that he hoped to rectify during his Prime Ministership.[1][15]: 493–494

Prior to Keating becoming Prime Minister, in April 1991 the final report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody had been published. Keating responded to the findings of the report by promising A$250 million in funding for programs to combat the problem and called for all levels of government to support them.[1][18]: 219

On 3 June 1992 the Mabo decision was handed down by the High Court of Australia acknowledging Aboriginal land rights and effectively overruling the terra nullius decision by the British Government in 1835 (Governor Bourke). This decision acknowledged that there was "a concept of native title at common law and that the source of the title was a traditional connection to or occupation of the land by Aboriginal and Islander people".[16]: 79 At a broader scale the decision found that native title had survived the 1788 declaration of British sovereignty of Australia and that it could be claimed on vacant or unallocated Crown land (that had not been converted to freehold title).[1][15]: 490–491

Keating saw this ruling as a key opportunity to support Aboriginal Land Rights as it was based on the truth of Australian history - that Aboriginal Australians had been disposed of their land by the British Invasion of 1788 and the lie of "terra nullius".[16]: 80 It was a decisive opening to legislating native title rights for Aboriginal people into the Australian common law if "a comprehensive, firm and quick legislative response" was undertaken.[16]: 76–77 To this end, his government moved towards giving the Mabo decision practical expression in Commonwealth law through a national legislative framework. This would stop any uncertainty about the ruling and prevent the states from acting together to extinguish any chance of native title within their borders.[1][15]: 491

The Mabo decision and Keating's desire to enact legislation to validate and develop this decision appear to have been one of the catalysts for what became known as the Redfern Speech, delivered in Redfern Park a few weeks before the 1993 federal election.[13] Keating wanted to take this opportunity to acknowledge the buried truths of Australian history and the wrongs and injustices of the dispossession of land from Australia's Indigenous peoples. He also wanted to celebrate the possibilities of the Mabo decision.[1]

Redfern appears to have been chosen as the place to give the speech due to the recognition among the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) that it was the location of a large Aboriginal population with strong views on social, political and legal change. Members of the Redfern community had contacted the PMO to tell them "in vehement terms that things were bad and getting worse and the government was useless and Keating no good". In this sense the decision reflected the importance of the Redfern Aboriginal community and the significant role it had played in Aboriginal resistance, activism, and self-determination movements since the 1960s/70s.[19][1][6][18]: 288

The Redfern Speech was delivered by Prime Minister Keating on 10 December 1992 at Redfern Park as part of the launch of Australia's program for the United Nations 1993 International Year of the World's Indigenous Peoples. In accordance with Keating's goals for his Prime Ministership, this speech was aimed at laying out the foundation of a new relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians based on a need for reconciliation. The speech was performed on a temporary stage set up in the northwest corner of Redfern Park facing rows of temporary seating set up across this section of the park. The crowd consisted of approximately 2,000 people of who the majority were Aboriginal Australians. The audience's reaction to the speech was initially quietly hostile with occasional jeers, however, as they realised that this speech was something different and unlike anything a Prime Minister had said before there were "hollers of approval" and scattered applause. The most important part of this speech has been described as "one of the most powerful, deeply moving, and beautifully phrased speeches given by a prime minister" and one which those who witnessed it have never forgotten:[1][15]: 488–489

The starting point might be to recognise that the problem starts with us non-Aboriginal Australians. It begins, I think with that act of recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practiced discrimination and exclusion. It was our ignorance and our prejudice. And our failure to imagine these things being done to us. With some noble exceptions, we failed to make the most basic human response and enter into their hearts and minds. We failed to ask, how would I feel if this were done to me? As a consequence, we failed to see that what we were doing degraded all of us As I said, it might help us if we non-Aboriginal Australians imagined ourselves dispossessed of land we had lived on for fifty thousand years-and then imagined ourselves told that it had never been ours. Imagine if ours was the oldest culture in the world and we were told that it was worthless. Imagine if we had resisted this settlement, suffered and died in the defence of our land, and then were told in history books that we had given up without a fight. Imagine if non-Aboriginal Australians had served their country in peace and war and were then ignored in history books. Imagine if our feats on sporting fields had inspired admiration and patriotism and yet did nothing to diminish prejudice. Imagine if our spiritual life was denied and ridiculed. Imagine if we had suffered the injustice and then were blamed for it. It seems to me that if we can imagine the injustice, we can imagine its opposite. And we can have justice.

Throughout the speech, Keating spoke frankly and honestly of the suffering and injustice the British invasion and settlement of Australia inflicted upon its Indigenous peoples and which continued into the present day through the creation of the modern Australian nation, its culture, and society. He also spoke of the enormous contributions they had made to the formation of the modern Australian nation, particularly to the fields of exploration, war, sport, art, literature, and music. However, he also called for historians to begin acknowledging the resistance and resilience Aboriginal people had shown throughout the invasion period (frontier war) onwards to the present day.[1][6]

Keating challenged Australians to "acknowledge that we now share a responsibility to put an end to the suffering" of indigenous Australians that are the result of our past actions.[16]: 149 At the same time Indigenous Australians also have a "right to know" that we as a nation have acknowledged our past wrongs and injustices to their peoples and our responsibilities in helping to put these wrongs right.[1][15]: 490–491

In the following days and weeks the speech created mass public debate on issues of Aboriginal equality, rights, and reconciliation and Indigenous views on and perspectives on Australian history. It was the media story and sections of the speech were replayed over and over on the radio and television coverage. Aboriginal leaders from across the country also contacted the Prime Minister's Office to express their gratitude and their belief that the speech was a good starting point on the road to reconciliation.[1][18]: 291 This speech was an important and monumental acknowledgement of an Indigenous perspective on Australian history. It was arguably the catalyst for the "history wars" throughout the mid to late 1990s.[1]

Following the Redfern Speech Keating's government embarked on the first ever full consultation between the Aboriginal community of Australia and the Federal Government to negotiate the details (the body of corporate and cultural law) of the Native Title Act, along with other interest groups (farmers and miners).[16]: 75

The Redfern Speech (or Address) is today considered to be a defining moment in the relationship between the Australian Nation (or Federal Government) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of this land. It marked a monumental turning point in the reconciliation process where for the first time the Federal Government publicly and officially acknowledged the dispossession of Indigenous Australians inflicted by British settlement. Ultimately, it has resulted in the new official perspective of Australia's history which is more inclusive of an Indigenous perspective, as well as bringing reconciliation and other Aboriginal issues into the public spotlight and consciousness. This paved the way for further steps towards reconciliation including PM Kevin Rudd's formal apology to Indigenous Australians for the past Federal Government practices and policies.[1][7]: 7–8

The Redfern speech is remembered as one of the great speeches of Australian history and still has meaning and impact for Australians - both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal. Its words continue to reverberate "because of the power and poetry of its words" which were the product of the unique combination of the performance (sentiment and substance) of Keating and the skill (or craft) of his speechwriter, Don Watson.[15]: 511 In August 2010 the video of the Redfern speech was added to the National Film and Sound Archives as a sign and tribute to its significance in Australian history. In 2011 the speech was also voted the third most "unforgettable speech" of all time by ABC Radio National listeners behind Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I have a Dream" speech.[1]

Description

The park contained typical components of a late nineteenth century Australian municipal park: the fountain and main gates (which survive) and the now vanished urns, bandstand, kiosk and sports pavilions. The surviving elements, and the documentary record, provides evidence of the efforts and generosity of local businessmen and aldermen, particularly John Baptist (junior) and George W. Howe, in contributing to the creation of a park as an amenity for their municipality.[1][2]

Whilst perimeter fig (Ficus spp., e.g. F. macrophylla: Moreton Bay fig; F. rubiginosa: Port Jackson fig; F. virens: white fig)[20] planting is typical of Sydney parks, the surviving mature planting is of both botanical and aesthetic significance for the layout, the range of specimen plantings, the use of rare Australian rainforest species and exotic palms recommended by successive directors of the Botanic Gardens, Moore and Maiden.[1]

The mature plantings of Redfern Park are a well-known local landmark, particularly the fig tree perimeter and the tall palms (Washingtonia robusta: Californian desert fan palm) and Norfolk Island pines (Araucaria heterophylla) marking entrances.[1]

The location and size of the park, the position of the entrances and the surrounding street and lane layout, reflects the subdivision of William Redfern's 40-hectare (100-acre) grant into the characteristic grid of colonial town planning. The archaeological record is likely to contain evidence of former uses and early improvements to the park.[1]

The choice of designer, the overall layout of the park, forming an urban lung, the addition of a children's playground, and the surviving requests for use of the park by local amateur clubs, reflect attempts by Reverend Boyce and the Aldermen to introduce benefi cial fresh air, sunlight, sport and active play into the daily life of the local workforce. Fitness has continued to be an importance aspect of the park's pattern of use, evidenced by children's holiday activities and National Fitness Camps.[1]

Two surviving structures from the original scheme: the Baptist Fountain and the main gates show the transition from a reliance on British design and manufacturing towards an Australian identity. The main gates are a rare surviving example of the use of Australiana in both metalwork and stonework dating from the early 1890s, which became a textbook example.[1][2]

Redfern Oval became the home ground of the South Sydney Rabbitohs from the 1948 season of the NSW Rugby League competition. This was their first home ground. Matches at the ground were popular for the first and only became more so with time. Improvements were continually made to the oval during the 1950s to provide better facilities for the spectators and players. This resulted in the slow removal of the other sporting facilities such as the tennis courts in 1958. Radio facilities were also likely provided early on so games could be broadcast. By the mid-1950s the oval needed a new grandstand. Consequently, the Reg Cope Grandstand was constructed between 1957 and 1959 along with other support facilities. This stand was named after Norman Reginald Cope a city alderman between 1950 and 1960.[7]: 12–13 Further upgrade works to Redfern Oval were carried out in the 1970s. In 1977 as part of a state government project to provide local employment and upgrade community facilities the earthen banks of the oval were upgraded and fencing installed around the oval. The street frontages along Phillip, Elizabeth, and Chalmers streets were also landscaped and beautified with colourful shrubs and trees.[1][7]: 15–16

Between 1948 and 1987 the South Sydney Rabbitohs used Redfern Oval as their home ground before moving to Sydney Football Stadium in 1988. During this time Rabbitohs supporters referred to the oval as "The Holy Land". From 1988 the Rabbitohs used the oval as a training ground with occasional pre-season or exhibition matches. In 1999 when the Rabbitohs were expelled from the new 14 team NRL structure a massive march of 40,000 people was held that began at Redfern Oval and proceeded to Sydney Town Hall to protest against the decision. Between 2007 and 2009 the City of Sydney redeveloped Redfern Oval to update its facilities to permit the Rabbitohs to resume their usage of the oval as a training ground from 2009.[1]

Heritage listing

As at 7 August 2018, The area which contains Redfern Park and Oval has always been a significant place for Aboriginal people. This part of Sydney was originally a biodiverse wetland that connected to the Tank Stream and a meeting place which included a corroboree ground. This connection to place has continued through major changes over time and is now represented by Redfern Park and Oval. The park and oval is a physical symbol of Aboriginal cultural, political, social and sporting movements which remain as cultural touchstones to teach future generations of Australians. Redfern, and by association, Redfern Park and Oval, is also a multicultural hub, with links to cultures worldwide from the late 19th century onwards. This was the location of Keating's 1992 Redfern speech which is of importance to all Australians. Redfern Park and Oval is a place of healing, a tangible link from the past to the future and a site of exceptional significance to the people of NSW.[1]

Redfern Park and Oval is a site of national and state historic significance for Aboriginal rights, recognition, and reconciliation through its connection with the Australia/Invasion Day 1988 Long March of Freedom, Justice, and Hope and the 1992 Redfern Speech of Prime Minister Paul Keating. Redfern Park is a place of very high contemporary social value for Aboriginal people as a landmark site in gaining Aboriginal rights and the assembly for protests and activism. It is still the site of Survival/Invasion Day events which are an annual commemoration of the Indigenous perspective on colonisation.[1]

Redfern Oval is of historic and social significance for NSW due to its long association with NSW Rugby League. The Redfern All Blacks principally staged training and matches at Alexandria and Redfern Ovals. Both the Redfern All Blacks and La Perouse United Aboriginal teams also potentially trained at Alexandria and Redfern Ovals during the early years of the Koori Knockout. Many Aboriginal Rugby League players and supporters (past and present) consider playing at Redfern Oval as special, because Redfern was "their place", whether they were visiting or it was their home ground. It was the original home ground of the South Sydney Rabbitohs, the oldest, and one of the original teams in the NSW Rugby Football League. This link continues today, with the Rabbitohs continuing connection with Redfern.[1]

Redfern Park has aesthetic significance at the state level due to its late nineteenth century park design by Charles O'Neill that has been accentuated by botanical plantings advocated by two successive directors of the Royal Botanical Gardens: Charles Moore (director 1848-1896) and Joseph H. Maiden (director 1896-1924). The park was tastefully and sympathetically refurbished in 2007-2009 and has been turned into an open green space in the heart of urban Redfern. Modern art installations added at this time contribute to the potential aesthetic significance. It retains a wide range of botanical species that as a group is potentially rare or uncommon in a state context.[1]

Redfern Park was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 21 September 2018 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Redfern Park and Oval is a site of national and state importance for Aboriginal rights, recognition, and reconciliation due to its connection with the Australia/Invasion Day 1988 Long March of Freedom, Justice, and Hope and the 1992 Redfern Speech of Prime Minister Paul Keating.[1]

Aboriginal communities from across the country came to Redfern Park on the 1988 Long March of Freedom, Justice, and Hope. This march was an important challenge to the dominant non-Indigenous representation of Australia Day. It was a demonstration of Aboriginal Australian's status as the original inhabitants of this land and a statement of their survival, and a protest against the deliberate omission of an indigenous perspective from Australian history. The march drew national and international attention to the plight of Indigenous communities across the country with relation to poor health, education, and welfare outcomes and high imprisonment rates and deaths in custody. Overall, this march was successful in putting Indigenous issues in public view, and arguably led to important gains in rights, recognition, and reconciliation in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[1]

Keating's Redfern Speech was a redefining moment in the relationship between the Australian Nation and its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The speech was remarkable in being delivered not in parliament to a largely European audience, but to an Aboriginal audience at Redfern - in the midst of an important urban Aboriginal community closely associated with the Aboriginal revolution in self-determination from the 1960s-1970s onwards. This speech marked a turning point in the official interpretation of Australia's history and an accommodation of the Indigenous perspective within it by the Federal Government.[1]

For Aboriginal Australians, Redfern Park and Oval are of high historical significance due to the landmark events that have occurred there in association with Invasion/Survival day and reconciliation. These late twentieth century events were important stepping stones in the forward movement of indigenous rights, recognition, and reconciliation throughout the late twentieth century.[1]

Redfern Oval is of historic significance due to its long association with NSW Rugby League. It may have been one of the earliest venues used in the competition following its inception. Most importantly this ground was the original home ground of the South Sydney Rabbitohs and served in this capacity from 1946 to 1988. The Rabbitohs are one of the original founding teams of the NSW Rugby Football League and are one of the two oldest remaining clubs in the competition. Due to the high number of Aboriginal players that have represented South Sydney and played within the Junior South Sydney Competition this ground is important in the history and evolution of Aboriginal participation in this sport. Despite no longer being a ground used for first grade competition, Redfern Oval retains its historic connection and association to rugby league through its use for annual "Return to Redfern" trial matches by the Rabbitohs and use in the Junior South Sydney Competition (second grade and below), as well as regular use for the Koori Knockout up to 2005. Ultimately, this ground has always been one of the main grounds in a thriving centre for this sport in Sydney and NSW, in general cultural and social terms, but also in relation to Aboriginal participation in Rugby League.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

Redfern Oval has associative significance at a state level through its strong historical association with the South Sydney Rabbitohs, the most successful and one of the two oldest remaining teams in the National Rugby League competition. In 2008 the Rabbitohs were recognised by the National Trust as a Community Icon held in high esteem by their supporters and the Australian public. This esteem was demonstrated by a march of 80,000 people from Redfern to Town Hall in November 2000 protesting the expulsion of the team from the NRL. Over its history the club has also had a proud and highly valued link to Australian Indigenous communities (through such all-Aboriginal teams as the Redfern All Blacks and La Perouse United playing in their local competitions) and the high number of Aboriginal players that have represented the side. Redfern Oval arguably embodies much of the spirit and passion and historical significance of the club due to its long association with the team (1946-present) and the important part this oval has played in the team's history and development. Although the upgrade of 2007-2009 removed all historic fabric from the oval, it enabled the ongoing use of the place by the Rabbitohs, and Redfern Oval is still considered to be of strong cultural and social significance for members of this club and Rugby League supporters in general.[1]

Redfern Oval has a special historical association with the Redfern All Blacks, the oldest Aboriginal Rugby League team in Australia. The Redfern All Blacks principally staged training and matches at Alexandria and Redfern Ovals. Both the Redfern All Blacks and La Perouse United Aboriginal teams also potentially trained at Alexandria and Redfern Ovals during the early years of the Koori Knockout, of which the Redfern All Blacks were one of the founding member clubs.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Redfern Park has aesthetic significance at a state level due to its late nineteenth century park design by Charles O'Neill that has been accentuated by botanical plantings advocated by two successive directors of the Royal Botanical Gardens: Charles Moore (director 1848-1896) and Joseph H. Maiden (director 1896-1924). The park was tastefully and sympathetically refurbished in 2007-2009 and has been turned into a beautiful open green (verdant) space in the heart of urban Redfern. Modern art installations added at this time have added to the potential aesthetic significance. It retains a wide range of botanical species that as a group is potentially rare or uncommon in a state context and demonstrates a richness of palate and unusually survivability in this context. The extant mature plantings are of aesthetic and botanical interest due to their layout and design and the wide range of specimen plantings including the use of rare Australian rainforest species (figs) and exotic palms. The perimeter of mature deciduous figs, which surrounds the park, and which has been accentuated by new plantings around the oval, is of particular aesthetic significance for the rainforest feel or character it brings to this urban environment (and the surrounding streetscape). These trees potentially date to the original planting regime of c.1886. The avenue of mature exotic palms is also of aesthetic significance for the spectacular view it creates across the centre of the park and the tropical silhouette (or profile) the present from either side. These trees likely date to the early twentieth century during lately planting programs. Ultimately, the park presents a wonderful balance of the old and the new with the restored historic fabric/memorials and original Victorian era design being sympathetically accentuated by new Aboriginally themed art installations and spaces, as well as sporting facilities and children's playgrounds. This design and work resulted in the park being awarded a prestigious Green Flag Award in 2014 which recognised it as one of the top parks internationally.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Redfern Park has social significance for the people of NSW and Australia as a place that can be (and is) effectively used to communicate and teach aspects of civics and citizenship, reconciliation and migration that are important to modern Australian values, tradition, and nationhood.[1]

Redfern Park is a place of very high contemporary social value for Aboriginal people as a landmark site in gaining Aboriginal rights and the assembly for protests and activism. It is still the site of Survival/Invasion Day events which are an annual commemoration of the Indigenous perspective on colonisation.[1]

Redfern Oval has social significance to the Aboriginal people of NSW due to the strong emotive and historic connection it has with the Redfern Aboriginal community, the Redfern All Blacks and the development of Aboriginal participation and support for Rugby League. Many Aboriginal Rugby League players and supporters (past and present) consider playing at Redfern Oval as special, because Redfern was "their place", whether they were visiting or it was their home ground.[1]

Redfern Park and Oval was, and continues to be a central meeting place for the Aboriginal community of Redfern and beyond as a place not only for activism and sporting events but a place for socialising and family connection.[1]

Gallery

Yabun Festival, Redfern Park Redfern (2005)

Yabun Festival, Redfern Park Redfern (2005)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 "Redfern Park and Oval". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H02016. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Redfern Park POM, 2006

- ↑ Craigie 2014:2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Murray, 2009

- 1 2 3 4 Pollen & Healy, 1988

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gilchrist, 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Thorp, 1994

- 1 2 Morris, Colleen, pers. comm., 27 April 2017

- ↑ Pamela Young, Sol Bellear

- 1 2 3 Little, 2009

- ↑ Norman, 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cook's obituary; 88 Documentary

- 1 2 Cook and Goodall, 2013:335

- ↑ Foley, 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bramston, 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Keating, 2011

- ↑ Keating interviews: Episode 4

- 1 2 3 Watson, 2002

- ↑ Keating Interviews: Extras - Native Title - Mabo

- ↑ Stuart Read, pers.comm., 14/8/2019

Bibliography

- Redfern Park Plan of Management. 2006.

- Bramston, T. (2016). Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader.

- Cook, K.; Goodall, H. (2013). Making Change Happen: Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics.

- Craigie, Cathy (2014). Home: Mapping the Stories of Redfern: Interviews, Anecdotes, and Snapshots from Redfern and its Surrounding Communities.

- Gilchrist, C. (2015). Redfern Park.

- Keating, Paul J. (2011). After Words: The Post-Prime Ministerial Speeches.

- Little, C. (2009). Through Thick and Thin: The South Sydney Rabbitohs and their Community.

- Murray, Dr. Lisa (2009). Redfern - a hive of industry.

- Norman, H. (2012). A modern day Corroboree – the New South Wales Annual Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout Carnival.

- Pearson, Noel (2009). Up from the Mission: Selected Writings.

- Pollen, Francis; Healy, G., eds. (1980). 'Redfern', in The Book of Sydney Suburbs.

- Thorp, Wendy (1994). Historical Analysis, Redfern Park, Redfern.

- Keating Speech may gain heritage status. 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Watson, Don (2002). Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: A Portrait of Paul Keating PM.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Redfern Park and Oval, entry number 2016 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2019 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 26 December 2019.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Redfern Park and Oval, entry number 2016 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2019 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 26 December 2019.