| Yangsui | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陽燧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阳燧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | bright mirror | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 양수 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 陽燧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 陽燧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ようすい | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fangzhu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 方諸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 方诸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | square all | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 방제 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 方諸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 方諸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ほうしょ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The sun-mirror (Chinese: 陽燧; pinyin: yángsuì) and moon-mirror (Chinese: 方諸; pinyin: fāngzhū) were bronze tools used in ancient China. A sun-mirror was a burning-mirror used to concentrate sunlight and ignite a fire, while a moon-mirror was a device used to collect nighttime dew by condensation. Their ability to produce fire and water gave them symbolic significance to Chinese philosophers, and they were often used as metaphors for the concepts of yin and yang (the sun-mirror representing yang and the moon-mirror representing yin).

Terminology

There are numerous Chinese names for the fire-producing "sun-mirror" and water-producing "moon-mirror".

These two bronze implements are literary metaphors for yin and yang, associating the "yang-mirror" yangsui with the Sun (a.k.a. tàiyáng 太陽 "great yang"), fire, dry, and round, and the "yin-mirror" fangshu with the Moon (tàiyīn 太陰 "great yin"), water, wet, and square.

Yangsui

The most common Chinese term for a sun-mirror, yangsui (陽遂 or 陽燧)[lower-alpha 1] is a compound word combining "yang" (meaning "sunshine", the same as in "yin and yang") with sui (遂; meaning to advance; accomplish; achieve or 燧; meaning to light a fire).[lower-alpha 2] The Hanyu Da Cidian unabridged Chinese dictionary[1] gives three meanings for yangsui (陽遂): "Also written 阳燧, a concave bronze mirror anciently used to start a fire from sunlight."; "appearance of clear, unobstructed flowing", which was first recorded in a poem (洞箫赋) by Wang Bao; and "an ancient type of chariot window that admits light", which was first recorded in the Book of Jin.

Three uncommon variant names for the concave fire-starting mirror are fúsuì (夫遂; with 夫 "that")[lower-alpha 3] used in the Rites of Zhou, jīnsuì (金燧; with 金 "metal")[lower-alpha 4] used in the Book of Rites (below), and yángfú (陽符)[lower-alpha 5] used in Taiping Yulan (below).[2]

English translations of the Chinese sun-mirror in classic texts (cited below) include:

Fangzhu

The name fangzhu (方諸; fāngzhū)[lower-alpha 6] combines fang (方; fāng), meaning "square; side; region", and zhu (諸; zhū), meaning "all; various". The Hanyu Da Cidian[10] gives two fangzhu meanings: "an ancient device used to collect dew in the moonlight in order to obtain water";[lower-alpha 7] "a mythical place where xian 'transcendents; immortals' reside".[lower-alpha 8]

The Taiping Yulan encyclopedia (published in 983) lists some synonyms of yangsui and fangzhu, "The yangsui or yángfú (陽符)[lower-alpha 9] obtains fire from the sun. The yīnfú (陰符)[lower-alpha 10] or yīnsuì (陰燧)[lower-alpha 11] obtains water from the Moon. They are copper amalgam mirrors, also named 'water and fire mirrors'."

Chenglupan (承露盤; chénglùpán; 'plate for receiving dew') is a near-synonym for fangzhu.[14] The huabiao, which is a type of Chinese architectural column traditionally erected in front of palaces and tombs, is topped by a mythical hou (犼; "a wolf-headed Chinese dragon") sitting on a round chenglupan cap.

There are comparatively fewer English translations of the Chinese moon-mirror, which lacks a direct translation equivalent and is more frequently romanized, include:

Mirror metaphors

Metaphorically using fangzhu and yangsui mirrors to represent yin and yang reflects a more commonly used Chinese philosophical metaphor of a mirror to denote the xin ("heart-mind"). For instance, the Zhuangzi famously says having a mirror-like xin represents

Do not be a corpse for fame,

Do not be a storehouse of schemes;

Do not be responsible for affairs,

Do not be a proprietor of knowledge.

Thoroughly embody unendingness and wander in nonbeginning. Thoroughly experience what you receive from heaven but do not reveal what you attain. Just be empty, that's all. The mind of the ultimate man functions like a mirror. It neither sends off nor welcomes; it responds but does not retain. Therefore, he can triumph over things without injury. (7)[16]

The stillness of the sage is not because stillness is said to be good and therefore he is still. It is because the myriad things are unable to disturb his mind that he is still. When water is still, it clearly reflects whiskers and brows. It is so accurate that the great craftsman takes his standard from it. If still water has such clarity, how much more so pure spirit! The stillness of the mind of the sage is the mirror of heaven and earth, the looking glass of the myriad things. (13)[17]

Many scholars of Chinese philosophy have analyzed the mirror metaphor for the xin. Harold Oshima explains that for a modern Westerner who regards a mirror as a commonplace looking-glass, this metaphor "appears quite pedestrian and unexciting" until one realizes that the ancient Chinese imagined mirrors "to possess broad and mysterious powers."[18] For instance, a mirror can reveal and control demons. The Baopuzi (above) says a Daoist practitioner entering the mountains would suspend a mirror on his back, which was believed to prevent the approach of demons—compare the European belief that a mirror is apotropaic toward vampires who are supposedly unable to produce a reflection. Oshima says the yangsui burning-mirror that miraculously produces fire best illustrates the "great sense of mystery surrounding mirrors". "Certainly this mirror symbolized a powerful connection with the greater powers of the heavens and, as such, would have served admirably as a model for the [xin]."

For the early Chinese, mirrors were not simply passive "reflectors" of information, they offered accurate and appropriate responses to whatever came before them. When placed before the sun—the ultimate yang 陽 phenomenon in the world—they respond with fire: the pure essence of yang. When placed before the moon—the ultimate yin 陰 phenomenon in the world—they respond with water: the pure essence of yin. Thus mirrors offer the paradigm for proper responsiveness: they reflect the true essence of the ultimate yin and yang—the alpha and omega of phenomena in early Chinese cosmology."[19]

Erin Cline says the early Chinese attributed mirrors to have a mysterious power and great religious significance. The ceremonial bronze fusui 夫遂 and yangsui 陽燧 mirrors were seen as active, responsive objects because they could be used to produce fire and water (two of the Five Phases).

When placed outside, concave mirrors focused sunlight to produce fire, while bronze mirrors gathered condensation in the light of the moon. But it was not simply the fact that mirrors had the power to gather or produce that made them objects of religious significance in ancient China; it was what they produced. Water and fire were thought to be the pure essences of yin and yang, respectively, and the fact that mirrors appeared to draw these substances from the Sun and Moon reinforced the cosmological power that was already associated with them.[20]

Textual examples

The Chinese classics contain early information about yangsui fire-mirrors and fangshu water-mirrors. The first two sources below are "ritual texts" of uncertain dates, and the others are presented chronologically.

Rites of Zhou

The (c. 2nd century BCE) Rites of Zhou is a compilation of Eastern Zhou (771-256 BCE) texts about government bureaucracy and administration. It describes two kinds of ritual officials making the purifying "new fire". The Directors of Fire Ceremonies (司爟; Siguan) used a fire-drill (鑽燧; zuānsuì), for which a variety of different woods were chosen at five periods during the year.[21] The Directors of Sun Fire (司烜氏; Sixuanshi) ceremonially used a yangsui to start the "new fire".

They have the duty of receiving, with the [fusui 夫遂] mirror, brilliant fire from the sun; and of receiving with the (ordinary) mirror [jian 鑒] brilliant water from the moon. They carry out these operations in order to prepare brilliant rice, brilliant torches for sacrifices, and brilliant water.[22]

The Rites of Zhou commentary by Zheng Xuan (127–200) glosses fusui as yangsui. The sub-commentary of Jia Gongyan (賈公彦) says the fusui is called yangsui because it starts a fire by means of the jīng (精 "spirit; essence") of the taiyang ("great yang; sun").

Book of Rites

Another ritual text similar to the Rites of Zhou, the 2nd-1st century BCE Book of Rites is a compilation of Eastern Zhou textual materials. "The Pattern of the Family" section lists idealized duties of family members. Sons and daughters-in-law are supposed to wear a utility belt that includes metal and wood (two of the Five Phases) suì fire-starters: jīnsuì 金燧 "burning-mirror" and a mùsuì 木燧 "fire-drill", which implies that fire-mirrors were quite commonly used among the ancient Chinese.[23]

From the left and right of the girdle [a son] should hang their articles for use—on the left side, the duster and handkerchief, the knife and whetstone, the small spike, and the metal speculum for getting fire from the sun [金燧]; on the right, the archer's thimble for the thumb and the armlet, the tube for writing instruments, the knife-case [or "needle-case" for a daughter-in-law], the larger spike, and the borer for getting fire from wood [木燧].[24]

Zheng Xuan's Book of Rites commentary glosses musui as zuānhuǒ 鑽火 "produce fire by friction". Kong Yingda (574 – 648) quotes Huang Kan 皇侃, "When it is daylight, use the jinsui to start a fire from the sun, when it is dark, use the musui to start a fire with a drill". The commentary of Sun Xidan 孙希旦 (1736-1784) says jinsui or yangsui 陽遂 "yang burning-mirrors" should ideally be cast on the Summer Solstice and yinjian 陰鑒 "yin mirrors" on the Winter Solstice.

The Chunqiu Fanlu (14), attributed to Dong Zhongshu (179–104 BC), says císhí 磁石 "lodestone" attracts iron and jǐngjīn 頸金 "neck metal; burning-mirror" attracts fire; Joseph Needham and Wang Ling suggest the name "neck metal" derives from either the mirror being hung round the neck, or because necks are concave things.[25]

Huainanzi

Liu An's (c. 139 BCE) Huainanzi "Masters of Huainan", which is a compendium of writings from various schools of Chinese philosophy, was the first text to record fangzhu dew-collectors.

Two Huainanzi chapters metaphorically use "sun and moon mirrors" to exemplify yang and yin categories and elucidate the Chinese notion of ganying "cosmic resonance" through which categorically identical things mutually resonate and influence each other. The yángsuì 陽燧 "burning-mirror" is yang, round, and sun-like; the fāngzhū 方諸 "square receptacle" is yin, square, and moon-like. The first context describes yangsui and fangzhu mirrors jiàn 見 "seeing" the sun and moon.

The Way of Heaven is called the Round; the Way of Earth is called the Square. The square governs the obscure; the circular governs the bright. The bright emits qi, and for this reason fire is the external brilliance of the sun. The obscure sucks in qi, and for this reason water is the internal luminosity of the moon. Emitted qi endows; retained qi transforms. Thus yang endows and yin transforms. The unbalanced qi of Heaven and Earth, becoming perturbed, causes wind; the harmonious qi of Heaven and Earth, becoming calm, causes rain. When yin and yang rub against each other, their interaction [感] produces thunder. Aroused, they produce thunderclaps; disordered they produce mist. When the yang qi prevails, it scatters to make rain and dew; when the yin qi prevails, it freezes to make frost and snow. Hairy and feather creatures make up the class of flying and walking things and are subject to yang. Creatures with scales and shells make up the class of creeping and hiding things and are subject to yin. The sun is the ruler of yang. Therefore, in spring and summer animals shed their fur; at the summer solstice, stags' antlers drop off. The moon is the fundament of yin. Therefore when the moon wanes, the brains of fish shrink; when the moon dies, wasps and crabs shrivel up. Fire flies upward; water flows downward. Thus, the flight of birds is aloft; the movement of fishes is downward. Things within the same class mutually move one another; root and twig mutually respond to each other [相應]. Therefore, when the burning mirror sees the sun, it ignites tinder and produces fire [故陽燧見日則燃而為火]. When the square receptacle sees the moon, it moistens and produces water [方諸見月則津而為水]. When the tiger roars, the valley winds rush; when the dragon arises, the bright clouds accumulate. When qilins wrangle, the sun or moon is eclipsed; when the leviathan dies, comets appear. When silkworms secrete fragmented silk, the shang string [of a stringed instrument] snaps. When meteors fall, the Bohai surges upward. (3.2)[26]

The second mentions some of the same yinyang and ganying folk-beliefs.

That things in their [various] categories are mutually responsive [相應] is [something] dark, mysterious, deep, and subtle. Knowledge is not capable of assessing it; argument is not capable of explaining it. Thus, when the east wind arrives, wine turns clear and overflows [its vessels]; when silkworms secrete fragmented silk, the shang string [of a stringed instrument] snaps. Something has stimulated [感] them. When a picture is traced out with the ashes of reeds, the moon's halo has a [corresponding] gap. When the leviathan dies, comets appear. Something has moved them. Thus, when a sage occupies the throne, he embraces the Way and does not speak, and his nurturance reaches to the myriad people. But when ruler and ministers [harbor] distrust in their hearts, back-to-back arcs appear in the sky. The mutual responses [相應] of spirit qi are subtle indeed! Thus, mountain clouds are like grassy hummocks; river clouds are like fish scales; dryland clouds are like smoky fire; cataract clouds are like billowing water. All resemble their forms and evoke responses [感] according to their class. The burning mirror takes fire from the sun; the square receptacle takes dew from the moon [夫陽燧取火於日方諸取露於月]. Of [all the things] between Heaven and Earth, even a skilled astrologer cannot master all their techniques. [Even] a hand [that can hold] minutely tiny and indistinct things cannot grasp a beam of light. However, from what is within the palm of one's hand, one can trace [correlative] categories to beyond the extreme end point [of the cosmos]. [Thus] that one can set up [these implements] and produce water and fire is [a function of] the mutually [responsive] movement of yin and yang of the same qi. (6.2)[27]

The Huainanzi commentary of Gao You (fl. 210 CE) says,

The burning mirror is of metal. One takes a metal cup untarnished with verdigris and polishes it strongly, then it is heated by being made to face the sun at noon time; in this position cause it to play upon mugwort tinder and this will take fire. The [fangzhu] is the Yin mirror [yinsui 陰燧]; it is like a large clam(-shell) [dage 大蛤]. It is also polished and held under the moonlight at full moon; water collects upon it, which can be received in drops upon the bronze plate. So the statements of our ancient teacher are really true.[25]

According to Needham and Wang,[28] this comparison between a fangzhu mirror that drew water from the moon and a bivalve shell reflects an ancient Chinese confusion between beliefs about moon-mirrors and beliefs that certain marine animals waxed and waned in correspondence with the moon. For example, the (c. 3rd century BCE) Guanzi says,

The virtue of a ruler is what all the people obey, just as the moon is the root and fount of all Yin things. So at full moon, shellfish [bangge 蚌蛤] are fleshy, and all that is Yin abounds. When the moon has waned, the shellfish are empty and Yin things weak. When the moon appears in the heavens all Yin things are influenced right down to the depths of the sea. So the sage lets virtue flow forth from himself, and the four outer wildernesses rejoice in his benevolent love.[29]

The authors compare Aristotle's (c. 350 BCE) Parts of Animals recording that some kinds of sea urchins were fat and good to eat at the full moon, which was one of the oldest biological observations about the lunar periodicity of the reproductive system of echinoderms, especially sea urchins.

A third Huainanzi chapter accurately describes the importance of finding a sui burning-mirror's focal point.

The Way of employing people is like drawing fire from a mirror [以燧取火]; if you're too far away [from the tinder], you won't get anything; if you're too close, it won't work. The right [distance] lies between far away and close. Observing the dawn, he [calculates] the shift [of the sun] at dusk; measuring the crooked, he tells [how far] something departs from the straight and level. When a sage matches things up, it is as if he holds up a mirror to their form; from the crooked [reflection], he can get to the nature [of things]. (17.227-228)[30]

The Huainanzi frequently uses the term suìhuǒ 燧火 "kindle a fire", for instance, in the second month of summer, the Emperor "drinks water gathered from the eight winds and cooks with fire [kindled from] cudrania branches (5.5)[31]

Lunheng

Wang Chong's (c. 80 CE) Lunheng mentions the fangzhu 方諸 in two chapters (46, 47), and the yangsui in five, written 陽遂 (8, 32) and 陽燧 (47, 74, 80).

The German sinologist Alfred Forke's[32] English translation of the Lunheng consistently renders fangzhu as "moon-mirror" and yangsui as "burning-glass", because two chapters describe "liquefying five stones" (wǔshí 五石) on a bingwu day (43rd in the 60-day sexagenary cycle) in the fifth lunar month. Forke circularly reasons that,[33] "If this be true, the material must have been a sort of glass, for otherwise it could not possess the qualities of a burning glass. Just flint glass of which optical instruments are now made consists of five stony and earthy substances—silica, lead oxide, potash, lime, and clay. The Taoists in their alchemistical researches may have discovered such a mixture." The French sinologist Berthold Laufer[34] refutes Forke's "downright literary concoction" of yangsui as "burning-glass" because Wang Chong's wushi 五石 "five stones" reference was a literary allusion to the Nüwa legend's wuseshi 五色石 "five-colored stone; multicolored stone", and because the Zhou Chinese did not have a word for "glass", which was unknown to them. Forke overlooked the (c. 320) Daoist text Baopuzi (below)[35] that also describes smelting the "five minerals" (identified as realgar, cinnabar, orpiment, alum, and laminar malachite) on the bingwu day of a fifth month to make magic daggers that will protect travelers from water demons.

Both Lunheng contexts about casting a yangsui "burning-mirror" on a bingwu day use the phrase xiāoliàn wǔshí 消鍊五石 "smelting five minerals". The first contrasts burning-mirrors and crooked sword-blades.

The laws of Heaven can be applied in a right and in a wrong way. The right way is in harmony with Heaven, the wrong one owes its results to human astuteness, but cannot in its effects be distinguished from the right one. This will be shown by the following. Among the "Tribute of Yu" are mentioned jade and white corals. These were the produce of earth and genuine precious stones and pearls. But the Taoists melt five kinds of stones, and make five-coloured gems out of them. Their lustre, if compared with real gems, does not differ. Pearls in fishes and shells are as genuine as the jade-stones in the Tribute of Yu. Yet the Marquis of Sui made pearls from chemicals, which were as brilliant as genuine ones. This is the climax of Taoist learning and a triumph of their skill. By means of a burning-glass [陽燧] one catches fire from heaven. Of five stones liquefied on the [Bingwu] day of the 5th moon an instrument is cast, which, when polished bright, held up against the sun, brings down fire too, in precisely the same manner as, when fire is caught in the proper way. Now, one goes even so far as to furbish the crooked blades of swords, till they shine, when, held up against the sun, they attract fire also. Crooked blades are not burning-glasses; that they can catch fire is the effect of rubbing. Now, provided the bad-natured men are of the same kind as good-natured ones, then they can be influenced, and induced to do good. Should they be of a different kind, they can also be coerced in the same manner as the Taoists cast gems, Sui Hou made pearls, and people furbish the crooked blades of swords. Enlightened with learning and familiarized with virtue, they too begin by and by to practise benevolence and equity. (8)[36]

Needham and Wang interpret this Lunheng passage as an account of making glass burning-lenses. Despite Forke's translation of suíhòu 隨侯, with suí 隨 "follow; comply with; the ancient state Sui" and hóu 侯 "marquis", as in the legendary Marquis of Sui's pearl; they translate "following proper timing", citing the Chinese alchemical term huǒhòu 火候 "fire-times; times when heating should begin and end", and reading hóu 侯 "marquis" as a miscopy of hòu 候 "time; wait; situation".

But by following proper timing (i.e. when to begin heating and how long to go on) pearls can be made from chemicals [yao 藥], just as brilliant as genuine ones. This is the climax of Taoist learning and a triumph of their skill. Now by means of the burning-mirror [yangsui] one catches fire from heaven. Yet of five mineral substances liquefied and transmuted on a [bingwu] day in the fifth month, an instrument [qi 器] is cast, which, when brightly polished and held up against the sun, brings down fire too, in precisely the same manner as when fire is caught in the proper way.[37]

Wang Chong gives three contrasts between "genuine" and "imitation" things: the opaque glass "jade" made by Daoist alchemists with the real thing; the artificially made "pearls" with true pearls; and the "instrument" made by liquefying five different minerals, which can concentrate the sun's rays like the traditional bronze burning-mirror. Furthermore, Needham and Wang question why the Lunheng specifies five different minerals,

Bronze would require only two ores, perhaps even only one, with possible addition of a flux. Glass needs silica, limestone, an alkaline carbonate, and perhaps litharge or the barium mineral, together with colouring matter. Of course, the text does not clearly tell us that lenses were being made; the instruments might have been simply glass mirrors imitating the bronze ones.[38]

Based on archeological finds of glass objects substituting for jade and bronze ones in tombs dating back to the Warring States period, Needham and Wang conclude that the Chinese were making glass lenses in the 1st century CE, and probably as far back as the 3rd century BCE.[38]

The second context explains ganying "cosmic resonance" with examples of bingwu burning-mirrors, moon-mirrors, and tulong 土龍 "clay dragons" believed analogously to cause rainfall like Chinese long dragons. It describes a dispute between Han astronomer Liu Xin, who used a clay dragon in a rain sacrifice, but could not explain the reason why it worked, when the scholar Huan Tan argued that only a genuine lodestone can attract needles.

The objection that the dragon was not genuine, is all right, but it is wrong not to insist on relationship. When an east wind blows, wine flows over, and [when a whale dies, a comet appears.] The principle of Heaven is spontaneity, and does not resemble human activity, being essentially like that affinity between clouds and dragons. The sun is fire, and the moon is water. Fire and water are always affected by genuine fluids. Now, physicists cast burning-glasses [陽燧] wherewith to catch the flying fire from the sun, and they produce moon-mirrors [方諸] to draw the water from the moon. That is not spontaneity, yet Heaven agrees to it. A clay dragon is not genuine either, but why should it not be apt to affect Heaven? With a burning-glass one draws fire from Heaven. In the fifth month, on a [bingwu] day at noon, they melt five stones, and cast an instrument with which they obtain fire. Now, without further ceremony, they also take the crooked hooks on swords and blades, rub them, hold them up towards the sun, and likewise affect Heaven. If a clay dragon cannot be compared with a burning-glass, it can at least be placed on a level with those crooked hooks on swords and blades. (47)[39]

A third Lunheng chapter, which mentions casting burning-mirrors on the fifth month but not the bingwu day, criticizes the Han philosopher Dong Zhongshu's belief that clay dragons could cause rain.

[E]ven Heaven may be induced to respond, by tricks. In order to stir up the heavenly fluid, the spirit should be used, but people will employ burning glasses [陽燧], to attract the fire from the sky. By melting five stones and moulding an instrument in the fifth month, in the height of summer, one may obtain fire. But now people merely take knives and swords or crooked blades of common copper, and, by rubbing them and holding them up against the sun, they likewise get fire. As by burning glasses, knives, swords, and blades one may obtain fire from the sun, so even ordinary men, being neither Worthies nor Sages, can influence the fluid of Heaven, as Tung Chung Shu was convinced that by a clay dragon he could attract the clouds and rain, and he had still some reason for this belief. If even those who in this manner conform to the working of Heaven, cannot be termed Worthies, how much less have those a claim to this name who barely win people’s hearts? (80)[40]

The other Lunheng reference to moon-mirrors mentions moon mythology about the moon rabbit and three-legged toad.

When we hold up a moon-mirror [方諸] towards the moon, water comes down. The moon approaching the Hyades or leaving the constellation of the ‘House’ from the north, it nearly always inevitably rains. The animals in the moon are the hare and the toad. Their counterparts on earth are snails and corn-weevils. When the moon is eclipsed in the sky, snails and corn-weevils decrease on earth, which proves that they are of the same kind. When it rains without ceasing, one attacks all that belongs to the Yin. To obtain a result one ought to hunt and kill hares and toads, and smash snails and corn-weevils. (46)[41]

Two chapters mention yangsui mirrors to express skepticism about the Chinese myth that the archer Houyi shot down nine of the Ten Suns (children of Di Jun and Xihe) that were burning up earth.

We see that with a sun-glass fire [陽遂] is drawn from heaven, the sun being a big fire. Since on earth fire is one fluid, and the earth has not ten fires, how can heaven possess ten suns? Perhaps the so called ten suns are some other things, whose light and shape resembles that of the sun. They are staying in the ‘Hot Water Abyss’, and always climb up Fu-sang. Yü and Yi saw them, and described them as ten suns. (32)[42]

These legendary references are to Fusang, Yu, and Yi.

The sun is fire: in the sky it is the sun, and on earth it is fire. How shall we prove it? A burning glass [陽遂] being held up towards the sun, fire comes down from heaven. Consequently fire is the solar fluid. The sun is connected with the cycle of ten, but fire is not. How is it that there are ten suns and twelve constellations? The suns are combined with these constellations, therefore [jia] is joined to [zi]. But what are the so called ten suns? Are there ten real suns, or is there only one with ten different names? (74)[43]

Jia 甲 and zi 子 are the first signs of the heavenly stems and earthly branches in the Chinese calendar.

Baopuzi

Three "Inner Chapters" of the (c. 320 CE) Baopuzi, written by the Jin Dynasty scholar Ge Hong, provide information about yangsui 陽燧 "burning-mirrors" and fangzhu 方諸 "dew-mirrors".

In Chapter 3 "Rejoinder to Popular Conceptions", Ge Hong mentions the commonly used sun and moon mirrors to answer an interlocutor who criticizes Daoist alchemical recipes for immortality as "specious … unreliable fabrications of wondermongers".

According to your argument, they would appear inefficacious, but even the most minor of them is not without effect. I have frequently seen people obtain water from the moon at night by means of a speculum, and fire from the sun in the morning by used of a burning-mirror [餘數見人以方諸求水於夕月陽燧引火於朝日]. I have seen people conceal themselves to the point of complete disappearance, or change their appearance so that they no longer seem human. I have seen them knot a kerchief, throw it to the ground, and produce a hopping hare. I have seen them sew together a red belt and thereby produce a wriggling snake. I have seen people make melons and fruit ripen in an instant, or dragons and fish come and go in a basin. All of these things occurred just as it was said they would.[44]

Chapter 4 "Gold and Cinnabar" refers to the yinyang mirrors in two contexts. The first describes an alchemical elixir method that uses a burning-mirror to create a mercury alloy dew-mirror.

There is also a [Minshan danfa 岷山丹法], found in a cave by [Zhang Kaita 張蓋蹋] as he was giving careful thought to such matters on Mount Min. This method forges yellow copper alloy to make a speculum for gathering water from the moon [其法鼓冶黃銅以作方諸]. It is then covered with mercury and its interior heated with solar essence (gathered by a burning-mirror) [以承取月中水以水銀覆之]. The taking of this substance over a long period will produce immortality. This same text also teaches us to place this elixir in a copper mirror coated with realgar, cover it with mercury, and expose it to the sun for twenty days, after which it is uncovered and treated. When taken in the form of pills the size of grams, washed down with the first water drawn from the well at dawn, for a hundred days, it makes the blind see, and by itself cures those who are ill. It will also turn white hair black and regrow teeth.[45]

The second fangzhu context describes using plates and bowls made from an elixir of immortality in order to collect the yè 液 "liquid; fluid; juice" (tr. "exudate") of the sun and moon, which also provides immortality.

A recipe for making "black amber sesame" [威喜巨勝] from Potable Gold is to combine Potable Gold with mercury and cook for thirty days. Remove, and fill a clay bowl with it. Seal with Six-One lute [a mixture of alum, arsenolite, salts, limestone, etc.], place in a raging fire, and cook for sixty double-hours, by which time it all turns to elixir. Take a quantity of this the size of a gram and you will immediately become a genie. A spatula of this elixir mixed with one pound of mercury will immediately turn it to silver; a pound placed over a fire, which is then fanned, will turn into a reddish gold termed "vermillion gold" [丹金]. If daggers and sword are smeared with it, they will ward off all other weapons within ten thousand miles. If plates and bowls are made of vermillion gold and used for drinking and eating, they will produce Fullness of Life. If these dishes are used to gather exudate of the sun and moon, as specula are used to gather lunar water [以承日月得液如方諸之得水也], the exudate will produce immortality when drunk.[46]

Chapter 16 "The Yellow and the White" uses the abbreviations zhu 諸 and sui 燧 along with fangzhu and yangsui to compare natural and artificial transformations.

What is it that the arts of transformation cannot do? May I remind my readers that the human body, which is normally visible, can be made to disappear? Ghosts and gods are normally invisible, but there are ways and means to make them visible. Those capable of operating these methods and prescriptions will be found to abound wherever you go. Water and fire are present in the sky, but they may be brought down with specula and burning-mirrors [水火在天而取之以諸燧]; lead is naturally white, but it can be reddened and mistaken for cinnabar. Cinnabar is naturally red, but it can be whitened to look like lead. Clouds, rain, frost, and snow are all breaths belonging to heaven and earth, but those produced by art differ in no way from the natural phenomena. Flying things and those that creep and crawl have been created in specific shapes, but it would be impossible ever to finish listing the thousands upon thousands of sudden metamorphoses which they can undergo. Man himself is the most highly honored member of creation and the most highly endowed, yet there are just as many instances of men and women changing into cranes, stones, tigers, monkeys, sand, or lizards. The cases of high mountains becoming deep abysses and of profound valleys changing into peaks are metamorphoses on an immense scale. It is clear, therefore, that transformation is something spontaneous in nature. Why should we doubt the possibility of making gold and silver from something different? Compare, if you will, the fire obtained with a burning-mirror and the water which condenses at night on the surface of a metal speculum [譬諸陽燧所得之火方諸所得之水]. Do they differ from ordinary water and fire?[47]

The Baopuzi also mentions míngjìng 明鏡 "bright mirror" magic, such as meditating on paired "sun" and "moon" mirrors to see spiritual beings, using mirror reflections to protect against shapeshifting demons,[48] and practicing Daoist multilocation.

At other times a bright mirror nine inches or more in diameter [明鏡徑九寸已上] is used for looking at oneself with something on the mind. After seven days and nights a god or genie will appear, either male, female, old, or young, and a single declaration on its part discloses automatically what is occurring at that moment a thousand miles away. Sometimes two mirrors are used and designated sun and moon respectively. Or four are used and designated as the four circumferences, by which is meant the front, rear, left, and right, to which each points when one looks into them. When four mirrors are used, a large number of gods are seen to appear; sometimes pell-mell, other times riding dragons or tigers and wearing hats and clothes of many colors, different from those seen in ordinary life. There are books and illustrations to document all this. (15)[49]

The spirits in old objects are capable of assuming human shape for the purpose of confusing human vision and constantly putting human beings to a test. It is only when reflected in a mirror that they are unable to alter their true forms. Therefore, in the old days, all processors entering the mountains suspended on their backs a mirror measuring nine inches or more in diameter [明鏡徑九寸已上], so that aged demons would not dare approach them. If any did come to test them, they were to turn and look at them in the mirror. If they were genii or good mountain gods, they would look like human beings when viewed in the mirror. If they were birds, animals, or evil demons, their true forms would appear in the mirror. If such a demon comes toward you, you must walk backward, turning your mirror toward it, in order to drive it away. Then observe it. If it is an aged demon it is sure to have no heels. If it has heels, it is a mountain god. (17)[50]

The preservation of Mystery-Unity [玄一] consists in imagining yourself as being divided into three persons. Once these three have become visible, you can continue to increase the number to several dozen, all like yourself, who may be concealed or revealed, and all of whom are automatically in possession of secret oral directions. This may be termed a process for multiplying the body. Through this method [Zuo Cu], [Ji Liao], and my uncle Ge Xuan could be in several dozen places at one time. When guests were present they could be one host speaking the guests in the house, another host greeting guests beside the stream, and still another host making cases with his fishing line, but the guests were unable to distinguish which was he true one. My teacher used to say that to preserve Unity was to practice jointly Bright Mirror [守一兼修明鏡], and that on becoming successful in the mirror procedure a man would be able to multiply his body to several dozen all with the same dress and facial expression. (18)[51]

Bencao gangmu

Li Shizhen's (1578) Bencao Gangmu classic pharmacopeia mentions both burning-mirrors and dew-mirrors.

Yangsui "burning-mirror" occurs with huǒzhū 火珠 (lit. "fire pearl/bead") "burning-lens" in the entry for àihuǒ 艾火 "igniting mugwort for moxibustion".

The fire used in cauterizing with mugwort ought to be fire really obtained from the sun by means of a sun-mirror [艾火] or fire-pearl (lens?) [火珠] exposed to the sun. Next in efficacy is fire obtained by boring into [huái 槐 "locust tree"] wood, and only in cases of emergency, or when it is difficult to procure such fire, it may be taken from a lamp of pure hempseed oil, or from a wax taper. (火1)[52]

Li Shizhen explains,[23] "[The yangsui] is a fire mirror made of cast copper. Its face is concave. Rubbing it warm and holding it towards the sun, one obtains fire by bringing some artemisia near it. This is what the [ZhouIi] says about the comptroller of light receiving the brilliant light from the sun by his fire speculum."

The huozhu "fire pearl" burning-lens was introduced into China during the Tang dynasty.[53] The (945) Old Book of Tang records that in 630, envoys from Chams presented Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649) with a crystalline huǒzhū 火珠 (lit. "fire pearl/bead") "fire orb; burning glass", the size of a hen's egg, that would concentrate the sun's rays and ignite a piece of punk. The envoys said they obtained this tribute gift in the country of the Luóchà 羅剎 "rakshasa creatures in Hindu mythology", probably imported into India from the Hellenistic Near East.[53] Needham and Wang say[54] Luocha "the country of the Rakshas", is not Sri Lanka, but rather Pahang, Malaysia. The (1060) New Book of Tang account says the year was 631 and the fire-orb came from Bali. The American sinologist Edward H. Schafer.[55] notes that the Chinese huozhu name reflects the Sanskrit agnimaṇi "fire jewel" name for burning-glasses, and later Tang dynasty sources use hybrid names like yangsuizhu "Solar-Kindling Pearl", showing that the crystal fire-orb was regarded as the legitimate successor of the ancient bronze burning-bowl.

Fangzhu occurs in the Bencao Gangmu entry for míngshuǐ 明水 "bright water" used in rituals (水1 天水類),[56] which is explained as fangzhu shui 方諸水 "dew-mirror water". [Chen Cangqi 陳藏器] says that it is a dabang 大蚌 "big oyster[-shell]" that, "when rubbed and held up towards the moon, draws some drops of water from it, resembling dew in the morning". [Other authors say] fang 方 means shi 石 "stone", or "a mixture of five stones", and zhu 諸 means zhū 珠 "pearl; bead". [Li Shizhen] "rejects all these explanations contending that the [fangzhu] was a mirror like the burning speculum, and similarly manufactured. This view is supported by the above quoted passage of the [Rites of Zhou], which expressly speaks of a mirror employed to obtain water from the moon. This very pure water was perhaps used at sacrifices."

Speculum metallurgy

Bronze mirrors have special significance within the history of metallurgy in China. In the archaeology of China, copper and bronze mirrors first appeared in the (pre-16th century BCE) "early metalwork" period before the Shang dynasty. Developments of metal plaques and mirrors appear to have been faster in the Northwestern Region where there was more frequent use of metals in the social life. In particular, the (c. 2050-1915 BCE) Qijia culture, mainly in Gansu and eastern Qinghai, has provided rich finds of copper mirrors.[57] Archeological evidence shows that yangsui burning-mirrors were "clearly one of the earliest uses to which mirrors were put, and the art of producing them was doubtless well known in the [Zhou dynasty]".[58] Chemical analyses of Chinese Bronze Age mirrors reveal that early technicians produced sophisticated speculum metal, a white, silvery smooth, high-tin bronze alloy that provides extremely reflective surfaces, used for mirrors and reflecting telescopes.[59] Among Chinese ritual bronzes, the most common mirror was jiàn 鑒 "mirror", which anciently referred to either a circular mirror, often with intricate ornamentation on the back, or a tall, broad dish for water.

The Kaogongji "Record Examining Crafts" section of the Rites of Zhou (above) lists six official standards for tóngxī 銅錫 copper-tin (Cu-Sn) bronze alloys to produce different implements; from the least tin (1 part per 5 parts copper) for "bells and sacrificial urns" to the most (1 part tin per 1 part copper) for "metallic mirrors", namely, the jiànsuì 鑒燧 "mirror-igniter" alloy.[60] However, these ratios are based on Chinese numerology instead of practical metallurgy.

Beyond about 32% the alloy becomes excessively brittle, and increasing tin content brings no further advantages of any kind; this the Han metallurgists evidently knew. Indeed they knew much more, for they almost always added up to 9% of lead, a constituent which greatly improved the casting properties. Han specular metal is truly white, reflects without tinning or silvering, resists scratching and corrosion well, and was admirably adapted for the purposes of its makers.[14]

Besides the Kaogongji half-copper and half-tin formula, other Chinese texts describe the yangsui and fangzhu speculum alloy as jīnxī 金錫 "gold and tin" or qīngtóngxī 青銅錫 "bronze and tin".[23]

Unless a mirror surface is truly smooth, image quality falls off rapidly with distance. Chinese bronze mirrors included both smooth plane mirrors and precisely curved mirrors of bright finish and high reflectivity. Needham and Wang[61] say, "That high-tin bronze (specular metal) was used from [Zhou] times onward is certain, and that it was sometimes coated with a layer of tin by heating above 2300°C. is highly probable; this would give at least 80% reflectivity." Later the tin was deposited by means of a mercury amalgam, as recorded in the Baopuzi (4, above).

Fu Ju Xiansheng 負局先生 "Master Box-on-his-Back" was the Daoist patron saint of mirror-polishers. The (c. 4th century CE) Liexian Zhuan says[62] Fu Chu "always carried on his back a box of implements for polishing mirrors, and used to frequent the market-towns of Wu in order to exhibit his skill in this work. He charged one cash for polishing a mirror. Having inquired of his host if there were any sick persons in the place, he would produce a drug made up into purple pills and administer these. Those who took them invariably recovered."

The casting of Chinese sun-mirrors and moon-mirrors ideally followed the principles of Chinese astrology, yinyang, and wuxing. The Lunheng (above) says yangsui and fangzhu mirrors should be smelted from five minerals when a bingwu (43rd of 60-day cycle) day occurs in the 5th lunar month. The (4th century) Soushenji explains, "The fire mirror must be cast in the 5th month on a [bingwu] day at noon, the moon mirror in the eleventh month on a [renzi] day at midnight." These times, the middle of summer and of winter are in harmony with the theory of the Five Elements.[23] Many early bronze mirrors have inscriptions mentioning the bingwu day, which was considered auspicious for casting operations since the cyclical bing was associated with the west and metal, while wu was associated with the south and fire; correspondingly, the moon-mirrors were cast on renzi days in the twelfth month, and these cyclical signs are associated with the complementary elements of water and wood.[38]

Cross-cultural parallels

The Chinese use of burning-mirrors has parallels in other civilizations, especially to produce ritual "pure fire", used as the source for lighting other fires.

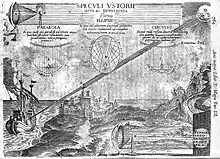

Burning-mirrors were known to the Greeks and Romans. Archimedes supposedly set fire to the Roman fleet with burning-mirrors in 212 BCE, when Syracuse was besieged by Marcus Claudius Marcellus.[63] Plutarch's (c. 1st century CE) Parallel Lives account of Numa Pompilius (r. 715-673 BCE) records the Vestal Virgins using burning-mirrors to light the sacred fire of Vesta.

If it (the fire) happens by any accident to be put out, … it is not to be lighted again from another fire, but new fire is to be gained by drawing a pure and unpolluted flame from the sunbeams. They kindle it generally with concave vessels of brass, formed by hollowing out an isosceles rectangular triangle, whose lines from the circumference meet in one single point. This being placed against the sun, causes its rays to converge in the centre, which, by reflection, acquiring the force and activity of fire, rarefy the air, and immediately kindle such light and dry matter as they think fit to apply.[64]

The striking contemporaneity of the first burning-mirror references in Chinese and European literature, probably indicates the spread in both directions of a technique originally Mesopotamian or Egyptian.[25]

In ancient India, the physician Vagbhata's Ashtānga hridayasamhitā mentions using burning-mirrors twice, to grind certain drugs on it, and to cauterize a rat bite wound.[65]

Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak's history of the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) records a pair of sacred sun and moon stones: Hindi sūryakānta "a crystal burning lens used to light the sacred fire" and chandrakānta (Sanskrit candrakānta "beloved by the moon") "a moonstone that drips water when exposed to moonlight".

At noon of the day, when the sun enters the nineteenth degree of Aries, the whole world being then surrounded by its light, they expose to the rays of the sun a round piece of a white and shining stone, called in Hindi sūryakānta. A piece of cotton is then held near it, which catches fire from the heat of the stone. This celestial fire is committed to the care of proper persons. …There is also a shining white stone, called chandrakānt, which, upon being exposed to the beams of the moon, drips water.[66]

Owing to the similarities of Chinese yangsui and fangzhu mirrors with Indian sūryakānta and candrakānta stones, Tang proposes a trans-cultural diffusion from China to the Mughal Empire.[67]

See also

References

- Biot, Édouard (1881). Le Tcheou-li ou Rites des Tcheou. 2 vols. (in French). Imprimerie nationale.

- Lun-hêng, Part 1, Philosophical Essays of Wang Ch'ung. Translated by Forke, Alfred. Otto Harrassowitz. 1907.

- Lun-hêng, Part 2, Philosophical Essays of Wang Ch'ung. Translated by Forke, Alfred. Otto Harrassowitz. 1911.

- de Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1892–1910). The Religious System of China: Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect, Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Connected Therewith (PDF). 6 volumes: pp. XXIV+360, 468, 640, 464, 464, 414. Vol. 6. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Laufer, Berthold (1915). "Optical Lenses: I. Burning-Lenses in China and India". T'oung Pao. 16: 169–228. doi:10.1163/156853215X00077.

- Sacred Books of the East. Volume 27: The Li Ki (Book of Rites), Chs. 1–10. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1885. Internet Archive.

- Luo, Zhufeng 羅竹風, ed. (1993). Hanyu Da Cidian 漢語大詞典. 13 vols. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. ISBN 9787543200135. CD-ROM ed. ISBN 962-07-0255-7.

- Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Mair, Victor H. Bantam Books. 1994. ISBN 9780824820381.

- The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China. Translated by Major, John S.; Queen, Sarah; Meyer, Andrew; Roth, Harold D. Columbia University Press. 2010. ISBN 9780231142045.

- Needham, Joseph; et al. (1962). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1. Physics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521058025.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press.

- Smith, Thomas E. (2008). "Qingtong 青童 Azure Lad". In Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei Pien of Ko Hung. Translated by Ware, James R. MIT Press. 1966. ISBN 9780262230223.

Notes

- ↑ Old Chinese *laŋsə-lu[t]-s

- ↑ Compare the mirrorless sui terms Suiren ("a mythical sage who invented friction firelighting" with flint (燧石; suìshí; 'stone')), mùsuì 木燧 (with "wood"), meaning either "hearth-board" or "fire-drill", and fēngsuì 烽燧 (with "beacon") "beacon-fire". Yángsuìzú 陽燧足 "sun-mirror feet" is an old Chinese name for "brittle star". Suì 燧 also had early graphic variants 鐆 and 䥙, written with the metal radical 金 specifying the bronze mirror.

- ↑ Old Chinese *[b]asә-lu[t]-s

- ↑ Old Chinese *k(r)[ә]msә-lu[t]-s

- ↑ Old Chinese *laŋ[b](r)o

- ↑ Old Chinese *C-paŋta

- ↑ the oldest usage example from the Huainanzi

- ↑ First recorded in the Zhen'gao, which says Fangzhu was named from being square, 1,300 li on each side, and 9,000 zhang high. Gustave Schlegel[11] says the yangsui mirror is perfectly round and the fangzhu is "perfectly square". This aligns with the association of yang with roundness and yin with "square-ness". Umehara described square mirrors believed to be from the Qin dynasty.[12] Qīngtóng 青童 "Azure Lad", which is a homophone of qīngtóng 青銅 (lit. "azure copper") "bronze", is one of the main deities in Shangqing Daoism, and lord of the mythic paradise Fangzhu "Square Speculum Isle" in the eastern sea near Mount Penglai.[13]

- ↑ Old Chinese *laŋ[b](r)o; with fú (符) meaning "tally; talisman; magic figure"

- ↑ Old Chinese *q(r)um[b](r)o; cf. Yinfujing "Hidden Tally Scripture"

- ↑ Old Chinese *q(r)umsə-lu[t]-s

- ↑ Luo 1993, v. 11 p. 1974.

- ↑ Luo 1993, v. 2 p. 1457.

- ↑ Legge 1885.

- 1 2 Forke 1907.

- ↑ de Groot 1910.

- 1 2 Needham et al 1962.

- ↑ Schafer 1963.

- 1 2 Ware 1966.

- 1 2 Major et al 2010.

- ↑ Luo 1993, v. 6 p. 1570.

- ↑ Schlegel, Gustave (1875), Uronographie Chinoise, 2 vols., Brill. p. 612.

- ↑ Umehara, Sueji (1956), "A study of the bronze ch'un [upward-facing bell with suspended clapper]", Monumenta Serica, 15: 142.

- ↑ Smith 2008, p. 803.

- 1 2 Needham et al 1962, p. 89.

- ↑ Smith 2008.

- ↑ Mair 1994, pp. 70-1.

- ↑ Mair 1994, pp. 119-20.

- ↑ Oshima, Harold H. (1983). "A Metaphorical Analysis of the Concept of Mind in Chuang-Tzu". In Mair, Victor H. (ed.). Experimental Essays on Chuang-tzu. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 75 (63-84). ISBN 9780824808365.

- ↑ Carr, Karen L. and Phillip J. Ivanhoe (2000), The Sense of Antirationalism: The Religious Thought of Zhuangzi and Kierkegaard, Seven Bridges Press. p. 56.

- ↑ Cline, Erin M. (2008), "Mirrors, Minds, and Metaphors", Philosophy East and West 58.3: 337-357. p. 338.

- ↑ Biot 1881, 2: 194.

- ↑ Tr. Needham et al 1962, p. 87, cf. Biot 1881, 2: 381.

- 1 2 3 4 Forke 1911, p. 497.

- ↑ Legge 1885, pp. 449, 450.

- 1 2 3 Needham et al 1962, p. 88.

- ↑ Major et al 2010, pp. 115–6.

- ↑ Major et al 2010, pp. 216–7.

- ↑ Needham et al 1962, p. 90.

- ↑ Tr. Needham et al 1962, p. 31.

- ↑ Major et al 2010, pp. 707–8.

- ↑ Major et al 2010, p. 188.

- ↑ Forke 1907; Forke 1911.

- ↑ Forke 1911, p. 496.

- ↑ Laufer 1915, pp. 182–3, 187.

- ↑ Ware 1966, p. 294.

- ↑ Forke 1907, pp. 377-8.

- ↑ Tr. Needham et al 1962, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Needham et al 1962, p. 113.

- ↑ Forke 1911, pp. 350–1.

- ↑ Forke 1911, p. 132.

- ↑ Forke 1911, p. 341.

- ↑ Forke 1911, pp. 272–3.

- ↑ Forke 1911, p. 412.

- ↑ Ware 1966, pp. 62–3.

- ↑ Ware 1966, pp. 83–4.

- ↑ Ware 1966, p. 90.

- ↑ Ware 1966, pp. 262–3.

- ↑ de Groot 1910, pp. 1000–5 discusses Chinese demon-conquering mirrors.

- ↑ Ware 1966, pp. 255–6.

- ↑ Ware 1966, p. 281.

- ↑ Ware 1966, p. 306.

- ↑ Tr. de Groot 1910, p. 947.

- 1 2 Schafer 1963, p. 237.

- ↑ Needham et al 1962, p. 115.

- ↑ Schafer 1963, pp. 237, 239.

- ↑ Forke 1911, pp. 497–8.

- ↑ Bai, Yunxiang (2013). Translated by Wang Tao. "A Discussion on Early Metals and the Origins of Bronze Casting in China". Chinese Archeology. 3 (1). pp. 157, 164 (157-165). Original Chinese text in Dongnan Wenhua 東南文化 (2002) 7: 25-37.

- ↑ Todd, Oliver Julian and Milan Rupert (1935), Chinese bronze mirrors; a study based on the Todd collection of 1,000 bronze mirrors found in the five northern provinces of Suiyuan, Shensi, Shansi, Honan, and Hopei, China, San Yu Press. p. 14.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph; Lu, Gwei-djen (1974). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 2, Spagyrical Discovery and Inventions: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Cambridge University Press. p. 198. doi:10.1086/ahr/82.4.1041. ISBN 9780521085717.

- ↑ Hirth, Friedrich (1907), Chinese metallic mirrors: with notes on some ancient specimens of the Musée Guimet, Paris, G. E. Stechert. pp. 217-8.

- ↑ Needham et al 1962, p. 91.

- ↑ Tr. Giles, Lionel (1979) [1948]. A Gallery of Chinese Immortals. London / New York City: John Murray / AMS Press (reprint). pp. 50–1. ISBN 0-404-14478-0.

- ↑ Simms, David L. (1977), "Archimedes and the Burning Mirrors of Syracuse", Technology and Culture 18.1: 1-24.

- ↑ Tr. Langhorne, John and William, trs. (1821), Plutarch's' Lives, J. Richardson. 1: 195.

- ↑ Laufer 1915, p. 220.

- ↑ Laufer 1915, pp. 221–2.

- ↑ Tang Bohuang 唐擘黃 (1935), "Yangsui chu huo yu fangzhu chu shui" 陽燧取火與方諸取水 [On the Statement that The Burning Mirror attracts Fire and the Dew Mirror attracts water], 國立中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊 5.2: 271-277.(in Chinese)

Further reading

- Benn, James A. (2008), "Another Look at the Pseudo-Śūraṃgama sutra", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 68.1: 57–89.

- Demieville, Paul (1987), "The Mirror of the Mind," trans. Neal Donner, in Peter N. Gregory, ed., Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought, University of Hawai'i Press, 13–40.

- Savignac, Jean de (1954), "La Rosée Solaire de l'Ancienne Égypte", La Nouvelle Clio 6: 345–353.

External links

- 陽燧, Zhou dynasty Yangsui, National Palace Museum (in Chinese)

- 青铜镜和阳燧,用途完全不同的两种铜镜, "Bronze mirrors and yangsui, two completely different mirrors", Toutiao News (in Chinese)

- 国之瑰宝:阳隧, "National Rarities: Yangsui", Changzhou Public Security Bureau (in Chinese)