| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

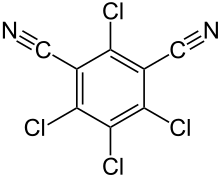

| Preferred IUPAC name

2,4,5,6-Tetrachlorobenzene-1,3-dicarbonitrile | |

| Other names

2,4,5,6-Tetrachloroisophthalonitrile Bravo Daconil Tetrachloroisophthalonitrile Celeste Bronco Agronil Aminil | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.990 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 3276, 2588 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8Cl4N2 | |

| Molar mass | 265.90 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white crystalline solid |

| Density | 1.8 g cm−3, solid |

| Melting point | 250 °C (482 °F; 523 K) |

| Boiling point | 350 °C (662 °F; 623 K) (760 mmHg) |

| 10 mg/100 mL[1] | |

| log P | 2.88–3.86 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H317, H318, H330, H335, H351, H410 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P261, P271, P272, P273, P280, P281, P284, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P310, P312, P320, P321, P333+P313, P363, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

| Related compounds | |

Related nitriles; organochlorides |

benzonitrile; hexachlorobenzene, dichlorobenzene, chlorobenzene |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

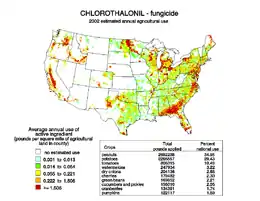

Chlorothalonil (2,4,5,6-tetrachloroisophthalonitrile) is an organic compound mainly used as a broad spectrum, nonsystemic fungicide, with other uses as a wood protectant, pesticide, acaricide, and to control mold, mildew, bacteria, algae.[2] Chlorothalonil-containing products are sold under the names Bravo, Echo, and Daconil. It was first registered for use in the US in 1966. In 1997, the most recent year for which data are available, it was the third most used fungicide in the US, behind only sulfur and copper, with 12 million pounds (5.4 million kilograms) used in agriculture that year.[3] Including nonagricultural uses, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates, on average, almost 15 million lb (6.8 million kg) were used annually from 1990 to 1996.[2]

Uses

In the US, chlorothalonil is used predominantly on peanuts (about 34% of usage), potatoes (about 12%), and tomatoes (about 7%), although the EPA recognizes its use on many other crops.[2] It is also used on golf courses and lawns (about 10%) and as a preservative additive in some paints (about 13%), resins, emulsions, and coatings.[2]

Chlorothalonil is commercially available in many different formulations and delivery methods. It is applied as a dust, dry or water-soluble grains, a wettable powder, a liquid spray, a fog, and a dip. It may be applied by hand, by ground sprayer, or by aircraft.[2]

Mechanism of action

Chlorothalonil reacts with glutathione giving an glutathione adduct with elimination of HCl. Its mechanism of action is similar to that of trichloromethyl sulfenyl fungicides[4] such as captan and folpet.[5]

Toxicity

Acute

According to the EPS, chlorothalonil is a toxicity category I eye irritant, producing severe eye irritation. It is in toxicity category II, "moderately toxic", if inhaled (inhaled LD50 0.094 mg/L in rats.) For skin contact and ingestion, chlorothalonil is rated toxicity category IV, "practically nontoxic", meaning the oral and dermal LD50 is greater than 10,000 mg/kg.[2]

Chronic

Long-term exposure to chlorothalonil resulted in kidney damage and tumors in animal tests.[2]

Carcinogenic

Chlorothalonil is a Group 2B "possible human carcinogen" (N.B. : in the Group 2A of International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC are the "probable human carcinogen" substances), based on observations of cancers and tumors of the kidneys and forestomachs in laboratory animals fed diets containing chlorothalonil.[2] To give context, the IARC evaluates Pickled vegetables (traditional Asian) as a Group 2B possible human carcinogen, and night shift work and drinking very hot beverages as Group 2A probable human carcinogen substances.

Environmental

Chlorothalonil was found to be an important factor in the decline of the honey bee population, by making the bees more vulnerable to the gut parasite Nosema ceranae.[6]

Chlorothalonil is highly toxic to fish and aquatic invertebrates, but not toxic to birds.[7]

At a concentration of 164 μg/L, chlorothalonil was found to kill a species of frog within a 24-hour exposure.[8]

Contaminants

Common chlorothalonil synthesis procedures frequently result in contamination of it with small amounts of hexachlorobenzene (HCB), which is toxic. US regulations limit HCB in commercial production to 0.05% of chlorothalonil. According to the EPA report, "post-application exposure to HCB from chlorothalonil is not expected to be a concern based on the low level of HCB in chlorothalonil. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin being one of the most potent carcinogens known is also a known contaminant".[2]

Environmental contamination

Chlorothalonil has been detected in ambient air in Minnesota[9] and Prince Edward Island,[10] as well as in groundwater in Long Island, New York[2] and Florida.[2] In the first three cases, the contamination is presumed to have come from potato farms. It has also been detected in several fish kills in Prince Edward Island.[11]

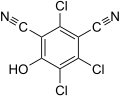

The main breakdown product of chlorothalonil is hydroxy-2,5,6-trichloro-1,3-dicyanobenzene (SDS-3701). It has been shown to be 30 times more acutely toxic than chlorothalonil and more persistent in the environment.[12][13] Laboratory experiments have shown it can thin the eggshells of birds, but no evidence supports this happening in the environment.[2]

In 2019, a review of the evidence found that "a high risk to amphibians and fish was identified for all representative uses", and that chlorothalonil breakdown products may cause DNA damage.[14][15] Around the same time, research indicated chlorothalonil and other fungicides to be the strongest factor in bumblebee population decline.[14]

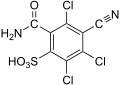

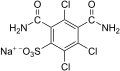

- Important metabolites of chlorothalonil

2,4,5-trichloro-6-hydroxyisophthalonitrile (SDS-3701)

2,4,5-trichloro-6-hydroxyisophthalonitrile (SDS-3701) Chlorothalonil sulfonic acid (R417888)

Chlorothalonil sulfonic acid (R417888) R471811

R471811

Gag order

Syngenta sued to stop communication by Swiss health authorities with the Swiss public regarding the "relevance" of specific metabolites of chlorothalonil that Swiss authorities detected in high concentrations in the groundwater from which hundreds of thousands of Swiss people obtain drinking water. The court banned Swiss health authorities from communicating with the public about the dangers posed by some of the metabolites.[16]

Bans

In March 2019, as a result of the previously mentioned research, the European Union banned the use of chlorothalonil[14] dated to take effect May 20, 2020.[17] Switzerland followed in December 2019.[18]

Removal

The removal of chlorothalonil and its metabolites is usually achieved by very expensive, technically complex and unecological methods such as reverse osmosis, nano- or microfiltration. In addition, dilution is achieved by mixing with uncontaminated water. However, this only reduces the concentration, the substances still remain in the water. In technologies based on membrane technology, the membranes must be cleaned regularly with chemicals, which is expensive and not ecological.

Recent research results from a Swiss company show very good results for the removal of chlorothalonil and its metabolites. In contrast to the conclusion described in the Eawag fact-sheet, it was also possible to remove the metabolites R471811 and chlorothalonil sulfonic acid from water using a filter material based on activated carbon. The first measurements did not even reach the detection limit. Thus, it was shown that it is possible to completely remove the pesticide residues.[19]

Production

Chlorothalonil can be produced by the direct chlorination of isophthalonitrile or by dehydration of tetrachloroisophthaloyl amide with phosphoryl chloride.[20] It is a white solid. It breaks down under basic conditions, but is stable in neutral and acidic media.[7] Technical grade chlorothalonil contains traces of dioxins and hexachlorobenzene,[2] a persistent organic pollutant banned under the Stockholm Convention.

References

- ↑ "Chlorothalonil". Pubchem.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Reregistration Eligibility Decision for chlorothalonil, US EPA, 1999.

- ↑ PESTICIDE USE IN U.S. CROP PRODUCTION: 1997 Archived 10 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine National Center for Food and Agricultural Policy, 1997.

- ↑ Tillman, Ronald; Siegel, Malcolm; Long, John (June 1973), "Mechanism of action and fate of the fungicide chlorothalonil (2,4,5,6-tetrachloroisophthalonitrile) in biological systems: I. Reactions with cells and subcellular components of Saccharomyces pastorianus", Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 3 (2): 160–167, doi:10.1016/0048-3575(73)90100-4

- ↑ Siegel, Malcolm R. (1970). "Reactions of certain trichloromethyl sulfenyl fungicides with low-molecular-weight thiols. In vivo studies with cells of Saccharomyces pastorianus". J. Agric. Food Chem. 18 (5): 823–826. doi:10.1021/jf60171a034. PMID 5474238.

- ↑ Jeffery S. Pettis, Elinor M. Lichtenberg, Michael Andree, Jennie Stitzinger, Robyn Rose, Dennis vanEngelsdorp "Crop Pollination Exposes Honey Bees to Pesticides Which Alters Their Susceptibility to the Gut Pathogen Nosema ceranae" PLOS One, 24 July 2013, Online: 9 April 2014.

- 1 2 Environmental Health Criteria 183, World Health Organization, 1996.

- ↑ Taegan McMahon, Neal Halstead, Steve Johnson, Thomas R. Raffel, John M. Romansic, Patrick W. Crumrine, Raoul K. Boughton, Lynn B. Martin, Jason R. Rohr "The Fungicide Chlorothalonil is Nonlinearly Associated with Corticosterone Levels, Immunity, and Mortality in Amphibians" Environ Health Perspectives, 2011, Online: 4 April. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002956

- ↑ Pesticides and Air Pollution in Minnesota: The Frequency of Detection of Chlorothalonil, a Fungicide Used on Potatoes. Pesticide Action Network North America, Oct 2007.

- ↑ White LM, Ernst WR, Julien G, Garron C, Leger M (2006). "Ambient air concentrations of pesticides used in potato cultivation in Prince Edward Island, Canada". Pest Manag. Sci. 62 (2): 126–36. doi:10.1002/ps.1130. PMID 16358323.

- ↑ "Island Fish Kills from 1962 to 2016" (PDF). Government of PEI. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ↑ Arena, Maria; Auteri, Domenica; Barmaz, Stefania; Bellisai, Giulia; Brancato, Alba; Brocca, Daniela; Bura, Laszlo; Byers, Harry; Chiusolo, Arianna; Court Marques, Daniele; Crivellente, Federica; De Lentdecker, Chloe; Egsmose, Mark; Erdos, Zoltan; Fait, Gabriella; Ferreira, Lucien; Goumenou, Marina; Greco, Luna; Ippolito, Alessio; Istace, Frederique; Jarrah, Samira; Kardassi, Dimitra; Leuschner, Renata; Lythgo, Christopher; Magrans, Jose Oriol; Medina, Paula; Miron, Ileana; Molnar, Tunde; Nougadere, Alexandre; Padovani, Laura; Parra Morte, Juan Manuel; Pedersen, Ragnor; Reich, Hermine; Sacchi, Angela; Santos, Miguel; Serafimova, Rositsa; Sharp, Rachel; Stanek, Alois; Streissl, Franz; Sturma, Juergen; Szentes, Csaba; Tarazona, Jose; Terron, Andrea; Theobald, Anne; Vagenende, Benedicte; Verani, Alessia; Villamar‐Bouza, Laura (January 2018). "Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance chlorothalonil". EFSA Journal. 16 (1): e05126. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5126. PMC 7009683. PMID 32625673.

- ↑ Cox, Caroline (1997), "Fungicide Factsheet: Chlorothalonil", Journal of Pesticide Reform, 17 (4): 14–20, archived from the original on 10 November 2010

- 1 2 3 Carrington, Damian (29 March 2019). "EU bans UK's most-used pesticide over health and environment fears". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ↑ "European Commission votes to ban fungicide Chlorothalonil".

- ↑ Le Monde, 27 Sept. 2022 "By-Products of Pesticide Banned in 2019 Found in Swiss Drinking Water, Syngenta, The Producer of The Fungicide Chlorothalonil, Has Sued Swiss Health Authorities for Making Public The Danger Posed by Certain Derivatives of The Pesticide,"

- ↑ National Farmers' Union of England and Wales. "Chlorothalonil use-by date approaching". NFU Online. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "Swiss ban widely-used pesticide over health and environment fears". swissinfo. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ↑ "BioGreen P". United Waters Int. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ Franz Müller; Peter Ackermann; Paul Margot. "Fungicides, Agricultural, 2. Individual Fungicides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.o12_o06. ISBN 978-3527306732.

External links

- Extension Toxicology Network: Chlorothalonil Pesticide Information Profile

- Chlorothalonil in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

- "2017 Pesticide Use Maps - Low". Water Resources. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- "2017 Pesticide Use Maps - High". Water Resources. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 16 March 2021.