| Church of San Francesco Grande | |

|---|---|

Detail of an engraving showing the church of San Francesco Grande in 1640. | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic |

| Location | |

| Location | Church of San Francesco Grande |

| Country | Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 45/27/50.00/N ; 9/10/38.50/E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Antonio Nuvolone (reconstruction de 1697) |

| Style | Lombard Romanesque and Gothic Architecture (before the 17th century) then Baroque (17th century reconstruction) |

| Demolished | 1806 |

The Church of San Francesco Grande (in Italian: Chiesa di San Francesco Grande) was an ancient church in Milan built in the 4th century and demolished in 1806. It was originally called Basilica di San Nabore after the saint whose remains it houses, but from the 13th century onwards, as the adjoining Franciscan monastery took possession of the monument, it took its new name from Francis of Assisi, founder of the order.

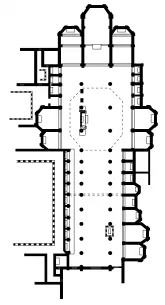

Before the end of the 17th century, the church adopted a rectangular plan. At first, in the part corresponding to the Basilica of Saint Nero, it had a mixture of Lombard Romanesque and Gothic architecture, to which was added a larger part due to the Franciscans. Later, the church continued to grow with the creation of numerous chapels by wealthy donors, who in exchange obtained the right to be buried in sepulchres created by renowned artists. After a first destruction at the end of the 17th century and a reconstruction some ten years later, in 1697, the architectural style of the church became baroque, but its plan remained very close to that of the original building, although it lost ground area.

The church of San Francesco Grande is known for having housed many works by renowned artists such as Bernardino Zenale and Bramante. The most famous work is Leonardo da Vinci's Virgin of the Rocks, which forms the central panel of an altarpiece in a chapel dedicated to the Immaculate Conception.

The building was decommissioned by decision of the Cisalpine Republic in 1798, and was definitively destroyed due to its dilapidation in 1806. Until then, it was the second largest church in the city, after the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin - that is, the Duomo of Milan.

Location

At the time of its destruction in 1806, the church of San Francesco Grande was located within the walls of the city of Milan in Piazza San Ambrose, named after the basilica that borders it.

The present-day Nirone and Santa Valeria streets ran alongside it.[1] In its place, the Garibaldi police barracks now stand.[2][3]

Church history

The history of the church of San Francesco Grande can be described in three main phases between its creation in the first centuries of the Christian era and its destruction in 1806.[4] This history benefits from the archaeological research carried out during several excavation campaigns: a first one in 1939-1940 under the management of Aristide Calderini,[5] then a second one in two phases conducted in 2006-2008 and a third one in 2011–2012 on the occasion of the creation of a car park on the Place Saint Ambrose.[6]

The early centuries of Christianity

In ancient times, the site to be occupied by the church of San Francesco Grande was located outside the city walls, a short distance from a gateway to the circus area and the imperial palace.[7]

From the 1st century of the Christian era onwards, this place was part of a vast space that developed as a necropolis made up of several funerary nuclei that were still commonly used until the 3rd century of the Common Era and then more sporadically afterwards.[8] These nuclei are organised around dwellings serving as churches, each with its own cemetery.[9] The complex thus houses the remains of ancient Christian martyrs, constituting the first Christian cemetery in Milan.[10] Saint Ambrose called it the "Cemetery of the Saints" (in Italian: Cimiterio de' santi)[11] or the "Cemetery of the Martyrs" (in Latin: ad martyres) in his memoirs. Excavations show that, despite the construction of churches, the area was used as a burial ground at a later date, with tombs dating from the 5th century.[12]

Amongst these houses, there is in particular that of Filippo de 'Oldani, a Roman consul of the time of Nero who secretly converted to Christianity and buried the remains of St. Gervais and St. Protais here.[5] This is where the church was built. During this time, what is now the primitive church is called, according to hagiographic writings,[7] "Polyandrion Caius et Filippo" (in Latin: Polyandrion Caij et Philippi) from the names of Filippo and Saint Caius, the third bishop of Milan.[5]

In the second century, it was consecrated as a basilica by the bishop of Milan, Saint Castriziano.[13] Then, in the following century, the remains of St. Nabor and St. Felix, who died during the reign of the co-emperor Maximian Hercules, were transferred there from Lodi by Bishop Materne of Milan (episcopate after 314 and before 342).[N 1][7] In fact, it is called the "Naborian Basilica" or "Basilica of Saint Nabore" ("San Nabore" in Italian).[10][14] The transfer is the occasion of festivities that take place in the presence of one of the reigning co-emperors of the Tetrarchy.[7]

All these saints were buried there before being transferred in June 386 by Saint Ambrose to the basilica he founded[6][15] on the site where Saint Victor had been buried, in the "house of Fausta", named after the daughter of Filippo.[9]

The building of the first real church in place of the domus Philippi is difficult to date, but an inscription on its walls several centuries later assures that it took place at the beginning of the tenth century.[16] The Italian priest and historian Paolo Rota (1832 - 1911), however, dates it slightly earlier, to the 7th century.[4]

From the arrival of the Franciscan friars to the first destruction

.png.webp)

In the 13th century, the Franciscans - whose order had just been created - settled in Milan. In 1222, they obtained a plot of land behind the Basilica of San Nabore, on which they built a convent and, in 1233, a chapel that they attached to the apse.[11] In 1256, by papal bull of Alexander IV, they received permission to build a church dedicated to the founder of the order, Saint Francis of Assisi.[17] On March 14, 1263, the Pope allowed them to take possession of the church of San Nabore. They then restructured the two buildings to form a single one and named it the "Church of Saint Francis".[4][18] The first occurrence of this name dates back to 1387 in a calendar of the order, thus confirming the fusion of the basilica and the chapel.[4] The promoters of the construction soon received rich donations from the faithful, who in exchange obtained the right to make it their burial place.[17]

In 1272 a bell tower was erected, but in 1551 it was lowered by a third of its height by the city governor - along with all the city's tallest bell towers - to prevent it from providing a sightline on the newly created city walls. This reduction corresponds to "40 fathoms" or 24 metres, which suggests that it was originally over 70 metres high.[19] Finally, the church was extended and modified between 1570 and 1571.[20]

The chapel and the brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception

In 1475, Father Master Stefano da Oleggio proposed the creation of a chapel[1] dedicated to the Virgin Mary and in particular to the Immaculate Conception.[21] This was taken from a plot of land called "Filippo's garden" (in Italian: orto di Filippo), located close to the atrium, against the chapel of St. John the Evangelist, going towards Via Santa Valeria and Via San Ambrogio. The masonry work was completed in May 1479. The chapel was the last to be built within the church.[1] To get an idea of this, the researchers suggest using the appearance of contemporary chapels built in other churches, such as the Brivio chapel built in 1484 in the Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio: it has a circular, kiosk-like shape. On the occasion of this creation, a secular brotherhood was founded: the Brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception. It is an assembly composed of members of the local aristocracy: the Terzago, Pietrasanta, Orrigoni, Mantegazza, Scanzi and Legnani families are represented,[1] but also the Cotio, Casati and Pozzobonelli families.[22] In fact, the brotherhood is richly endowed.[23]

The object of this brotherhood was new: to promote and defend the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, which was still very much debated since it had only been accepted since 1470 by the papacy, which did not officially proclaim it until 1854; the novelty and precariousness of this dogma thus partly explain the prudence of its members at the time of the reception of The Virgin of the Rocks.[24] An agreement was signed on June 1, 1478, before Antonio di Capitani, notary of the nearby parish of Santa Maria alla Porta, whose services the brotherhood had often used since its creation, defining the links between the newly created brotherhood and the monastery responsible for the church. On this occasion, several prescriptions were issued by those in charge of the church, including one of an absolute nature, which forbids the creation of any opening to the outside of the building.[1]

In May 1480, the work of decorating the chapel was completed,[1] in particular the ceiling, decorated by two artists named Francesco Zavatari and Giorgio della Chiesa:[25] the contractual description of this decoration indicates a representation of God surrounded by a glory of seraphim and four other panels with animals.[1] A few weeks before the end of this work, in April 1480, the woodcarver Giacomo del Maino (before 1469 - 1503 or 1505) was commissioned to build the wooden structure of a large altarpiece, the Altarpiece of the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception.[26] The altarpiece was delivered on August 7, 1482, and still needs to be decorated.[27] In that year, a new prior of the confraternity is appointed, Giannantonio da Sant'Angelo.[1] Painters were commissioned to decorate the structure: the brothers Evangelis and Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis and Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo da Vinci created the painting of The Virgin of the Rocks, which the chapel would house until the end of the 18th century, Ambrogio painted the Angel musicians on the side panels and Evangelis gilded and decorated the sculpted parts.[1][27] On the occasion of the creation of this altarpiece, the confraternity showed, despite its relative wealth, a great deal of penny-pinching, as evidenced by the dilatory measures and vague and unfulfilled promises for the remuneration of the participating artists.[27]

The chapel was destroyed in 1576.[28] However, the brotherhood continued its activities: the chapel of Saint John the Baptist, situated to the right of the choir, was allocated to it. This chapel was renamed the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception and the altarpiece was moved there.[29] Around 1635, a testimony indicates that the altarpiece is surrounded by other "small paintings" which are also said to be by Leonardo da Vinci.[30]

Three centuries after its creation, in 1781, the brotherhood was dissolved:[31] its goods were then taken over by the brotherhood of Saint Catherine de la Roue and sold between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, starting with La Vierge aux rochers in 1785.[29]

Final period: from the reconstruction of 1697 to the second destruction

At the end of the 17th century, the church was in a state of relative disrepair due to lack of maintenance.[32] From 1685 onwards, the decision was taken to transform the oldest part of the church. However, on September 6, 1688, the related work led to the collapse of the façade.[33] It was then decided not to restore but to rebuild the building. All the authorisations were received by the monastery on October 3, 1689:[34] The work of partial destruction and then reconstruction then began and lasted until 1697.[17] The new church was slightly enlarged - encroaching on a portion of Santa Valeria Street, which runs alongside the church - and lost some of its length[34] as part of it was not rebuilt and became the new atrium.[33] In the end, the church's footprint was reduced, but this did not prevent it[17] from remaining the second largest religious building in Milan after the city's Duomo.[32] The architect responsible for the new plans, Antonio Nuvolone, used a very different style from the old one.[35]

When Napoleon Bonaparte created the Cisalpine Republic in 1797, the church was damaged and looted, especially the relics of the saints that had been kept there since medieval times.[3] The following year, the Franciscan monastery was suppressed as part of the laws on the suppression of religious congregations.[17] From then on, the church and the monastery were used successively as a hospital, a warehouse and an orphanage.[36] A few years later, in 1806, the church of San Francesco Grande, considered obsolete and dangerous, was destroyed.[3] The materials resulting from the demolition were reused to build the Arco della Pace.[37] The work continued until 1813.[38] Finally, a barracks was built on its site: its plans were created by Lieutenant-Colonel Girolamo Rossi and its foundations partially used those of the pre-existing church. Until 1843 the barracks were called the Caserma dei Reali Veliti, after the military corps set up by the Cisalpine Republic,[33] and from then on the Garibaldi barracks.[2]

Building description

Appearance of the church prior to 1688

While the appearance of the church before the arrival of the Franciscans is not known,[39] the appearance of the building after the 13th century is, as it is described in numerous written,[40][41] drawn[42] and archaeological documents.[43]

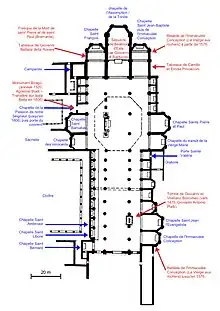

The church is 114 metres long and 30 metres wide.[33] It is made up of three parts and thus comprises three naves that can be described as follows, starting from the atrium: first, comprising the first five vaults, a first part in Gothic style; then, on the next four vaults, the ancient basilica of San Nabore, the oldest part of the building, adopting typical Lombard Romanesque forms;[44] finally, the largest body (starting at the chapels of the Innocents and of the Transit of the Virgin Mary included), with aisles twice as wide as those of the previous parts, and which corresponds to the addition of the Franciscans in the 13th century.[33]

The boundary between the two buildings - the Franciscan church on one side and the Naborian basilica and its Gothic addition on the other - is visible from the outside through two roof heights, the Franciscan part being the higher. The building is bordered by the Franciscan cloister and a campanile;[4] researchers refer to this complex as the "monastic complex of San Francesco Maggiore".[3] The external appearance of the building before its destruction-reconstruction in 1688 is described by a testimony in a letter dated 1686: "The old red brick facade, five windows, towers, crosses, with three doors, the middle round, and many elements with sepulcri et statuae".[45] A rose window is visible on the upper central part of the building's façade.[46]

As for the interior, the same witness describes it as follows: "The interior then consists of three vaults decorated on either side with twelve arches and numerous other stone columns with Corinthian but crude capitals, to the number of eighteen with eight windows on each side.[47]" Furthermore, the commissioning contract between Leonardo da Vinci and the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception in 1483 for The Virgin of the Rocks indicates that the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception was located at the beginning of the church, closest to the atrium, on the right-hand side, and that it did not have any openings to the outside - its promoters were forbidden by the church authorities to create one.[1]

- Representations of the church before 1688

Antoine Du Perac Lafrery, Plan of Milan (Detail), 1573, Milan, Sforza Castle, Civica raccolta delle stampe Achille Bertarelli.

Antoine Du Perac Lafrery, Plan of Milan (Detail), 1573, Milan, Sforza Castle, Civica raccolta delle stampe Achille Bertarelli. Nunzio Galliti, Plan of Milan celebrating the liberation of Milan from the plague (Detail), 1578, Milan, Sforza Castle, Civica raccolta delle stampe Achille Bertarelli.

Nunzio Galliti, Plan of Milan celebrating the liberation of Milan from the plague (Detail), 1578, Milan, Sforza Castle, Civica raccolta delle stampe Achille Bertarelli. Marc'Antonio Barateri, The Great City of Milan (Détail), 1629, Milan, Sforza Castle, Civica raccolta delle stampe Achille Bertarelli.

Marc'Antonio Barateri, The Great City of Milan (Détail), 1629, Milan, Sforza Castle, Civica raccolta delle stampe Achille Bertarelli. Giovanni Battista Bonacina, Plan of Milan (detail), 1640.

Giovanni Battista Bonacina, Plan of Milan (detail), 1640.

Appearance post 1697

.png.webp)

The building was designed by Antonio Nuvolone[35] in the Baroque style.[32] From the outside, the façade was remodeled and the dome above the apse took on a completely different shape.[48] In addition, the monument loses more than a quarter of its length out of the 114 metres it had previously measured,[34] as the entire part corresponding to the former Basilica of San Nabore is not rebuilt on its first five pillars and becomes the church's new atrium (i.e. its entrance courtyard surrounded by porticoes).[33] Finally, a new doorway was opened towards Via Santa Valeria.[49]

The interior is described by a testimony from 1696 which mentions a "vast, large, beautiful and dazzling choir, decorated with stucco and very clear thanks to the width of the windows".[50] Similarly, the chapels that have been preserved have been enlarged.[51] Several accounts also describe the richness of the materials used: stucco, Carrara marble, black marble.[52]

However, not everything has been altered, since part of the apse has remained as it was, with the exception of its upper part and especially its openings.[48]

Cultural dimension of the church

Princely chapels and gentilices

Soon after the construction of the church began in the 11th century, the Franciscans received generous donations from the aristocracy. In return, they were allowed to make it their burial place, both for themselves and for their families.[17] This patronage of a certain political elite is reflected in the creation of dedicated chapels. Indeed, as the historian Patrick Boucheron, a specialist in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, notes, "the proliferation of gentilice chapels in Milan can be seen as the architectural translation of a political requirement for the 'social visibility' of the patronage of the oligarchy in the service of the prince".[53]

Beatrice d'Este had the Trinity Chapel built in 1330 and was buried there in 1334.[54] Her sepulchre bears the symbol of her first husband Ugolino Visconti (the cockerel), as well as of her second husband Galeas I Visconti (the viper).[55] In 1399, Luchino Visconti, known as "Novello" (1346-1399), son of the noble condottier Luchino Visconti (c. 1287–1349), founded the Chapel of the Innocents.[54] The wealthy knight Arrigolo Arconati, a relative of Francesco Sforza, had the Chapel of Saints Peter and Paul built. At the end of the 15th century, Francesco Maggi inaugurated a sepulchral monument for his family in the chapel of Saint Libor. In 1426, the Borromeo family founded the Chapel of St. John the Evangelist. The wealthy knight Arrigolo Arconati, a relative of Francesco Sforza, had the Chapel of Saints Peter and Paul built.[54] At the end of the 15th century, Francesco Maggi inaugurated a sepulchral monument for his family in the chapel of Saint Libor.[54] In 1426, the Borromeo family founded the Chapel of St. John the Evangelist.[54]

The history of some of the chapels bears witness to the influences and confiscations that surrounded the church. Thus, the chapel of St. John the Baptist was first founded by the della Torre family; but when the Visconti family eliminated the latter at the end of the 13th century, they took over the premises. Beatrice d'Este, in particular, took charge of its decoration in 1333, before the condottier Francesco Bussone da Carmagnola - a commoner who joined the Visconti family by marriage - was buried here in 1432.[54] The monument was destroyed with the church at the beginning of the 19th century.[56] Finally, when the chapel of the Immaculate Conception was destroyed in 1576, the altarpiece of the same name was moved to the chapel of St. John the Baptist, which was renamed the Immaculate Conception.[29]

Historical objects and related works of art

Among the historical testimonies in the church are many relics, such as the skeleton of St. Desiderius, the skull of St. Matthew the Apostle, the skulls of St. Odelia and St. Ursula, a tooth of St. Lorenzo, the bones of St. Mary Magdalene, the bones of the Roman saint Caius and the bones of Pope St. Sixtus.[19]

In addition, the monument has benefited from the prestigious contributions of great artists over the centuries. One of the first was Giovanni di Balduccio, who created the tomb of Beatrice d'Este, now destroyed.[57] Between 1440 and 1447, Andrea and Filippo da Carona sculpted the lower part of the funerary monument of Vitaliano I and Giovanni Borromeo, and after 1478, Giovanni Antonio Piatti and his collaborators (Adamo da Barengo, Martino and Protasio Benzoni, Antonio and Benedetto da Briosco, Francesco Cazzaniga, Giacomo da Fagnano and others) created the upper part. The structure was originally located between the pillars in front of the chapel of St John the Evangelist, and was later transferred to the Borromeo Palace on the Isola Bella, where it remains today.[58] Between 1479 and 1500, Bramante painted in fresco the Death of St. Peter and St. Paul.[59]

Between 1495 and 1500, Vincenzo Foppa painted the panels of an altarpiece that seems to have been intended to decorate the chapel of St. John the Evangelist belonging to the Borromeo family. The altarpiece was dismantled at an unknown date, perhaps when the church was destroyed, and the whereabouts of the works are only known from the beginning of the 20th century. In any case, two panels representing Saint Bernardine and Saint Anthony of Padua are kept in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It seems that two other panels belonging to the upper register can be identified with the paintings representing an Angel Gabriel and an Annunciation to the preserved Virgin in the Borromeo Palace in Isola Bella.[60]

Later, after 1503, the altarpiece of the Immaculate Conception was installed, consisting in particular of Leonardo da Vinci's Virgin of the Rocks (completed only in 1508) and framed by the Angel musicians by Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis and Francesco Napoletano. The ensemble was exhibited in the chapel of the Immaculate Conception (first chapel on the right) and then moved in 1576 to the chapel of St John the Baptist (on the right of the choir), which was then called the chapel of the Immaculate Conception. The works left the church separately, in 1781 for The Virgin and the Rocks and in 1798 for the Musician Angels.[29] The structure is considered lost since the destruction of the church in 1806.[2]

In 1510, Bernardino Zenale painted the Madonna and Child between St. Ambrose and St. Jerome, which is now in the Denver Art Museum.[61] In 1522, Agostino Busti, known as "Bambaia", created the Birago Monument in the Chapel of the Passion of Our Lord. It was transferred in 1606 to the Borromeo Palace on the Isola Bella when the chapel was demolished to create an access to the adjoining cloister. Around 1510, the Franciscan friars commissioned Ambrogio Borgognone to paint a picture entitled St. Francis Receives the Stigmata, depicting the holy founder of their order. The painting is now in the Diocesan Museum in Milan.[62]

The destruction of the church in 1807 was carried out with no regard for the works on display: explosives were even used, without any real precautions, to the extent that the neighbouring buildings were damaged. Many statues, decorations, tombstones and frescoes remained in the monument while these operations were underway.[63] The ecclesiastical authorities were moved by this and obtained permission from the minister in charge to recover the remaining works, which the latter accepted on condition that "this would not cost the administration anything".[63][N 2] It was under these difficult conditions that the sarcophagus of Saints Nabor and Felix was removed from a chapel. It is now kept in the Basilica of Saint Ambrose.[64]

- Safeguarded sculptures and their current location

Sarcophagus of Saints Nabor and Felix, Milan, Basilica of San Ambrosio.

Sarcophagus of Saints Nabor and Felix, Milan, Basilica of San Ambrosio..png.webp) Andrea and Filippo da Carona and Giovanni Antonio Piatti, Funerary monument of Vitaliano and Giovanni Borromeo, between 1440 and 1478, Isola Bella, Borromeo Palace.

Andrea and Filippo da Carona and Giovanni Antonio Piatti, Funerary monument of Vitaliano and Giovanni Borromeo, between 1440 and 1478, Isola Bella, Borromeo Palace. Agostino Busti also known as "Bambaia", Monument Birago, 1522, Isola Bella, Borromeo palace.

Agostino Busti also known as "Bambaia", Monument Birago, 1522, Isola Bella, Borromeo palace.

- Saved paintings and their current location

Bernardino Zenale, Virgin and Child between St. Ambrose and St. Jerome, ca. 1510, Denver Art Museum .

Bernardino Zenale, Virgin and Child between St. Ambrose and St. Jerome, ca. 1510, Denver Art Museum . Ambrogio Borgognone, Saint Francis receives the stigmata, ca. 1510, Milan, Museo diocesano.

Ambrogio Borgognone, Saint Francis receives the stigmata, ca. 1510, Milan, Museo diocesano.

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Bishop Materne of Milan also buried St. Victor in the nearby "domus Aurelia". According to the Milanese corpus studied by the researcher Elisabeth Paoli, Materne was himself buried ad sanctum naborem and was thus one of the saints whose body was buried in the church of San Francesco Grande

- ↑ This is how the letter dated 10 July 1807 addressed to the Minister by the Provost of the Church, Gabrio Maria Nava, was found: "Taking advantage of Your Excellency's gracious condescension, I take the liberty of submitting to you a list of objects from the Inscriptions and Monuments which are of interest to the fine arts and the Holy Land and which, in the present destruction of the Naborrian Basilica of St. Francis, deserve to be removed from ruin and preserved. If Your Excellency would deign to ask that the objects and writings, as well as others that may be discovered, be removed to the Ambrosian Basilica where other ancient objects have already been placed on the occasion of the desecration of the altars of the Church of St. Francis. I would be grateful if they could be placed in the aforementioned Basilica in the most appropriate manner in the light of science, history and the arts. With all my feelings of great veneration and profound respect. Gabrio Maria Nava "

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gerolamo Biscaro (1910)

- 1 2 3 Alberto Angela (2018, p. 142)

- 1 2 3 4 Paolo Rotta (1891, p. 115)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paolo Rotta (1891, p. 114)

- 1 2 3 Aristide Calderini (1940, pp. 198–199)

- 1 2 Marco Sannazaro (2015, pp. 38)

- 1 2 3 4 Marco Sannazaro (2015, p. 36)

- ↑ Marco Sannazaro (2015, pp. 36 and 38)

- 1 2 Louis Baunard (1899, p. 55)

- 1 2 Paolo Rotta (1891, pp. 113–114)

- 1 2 Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 201)

- ↑ Marco Sannazaro (2015, p. 40)

- ↑ Paolo Rotta (1891, p. 113)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 198)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, pp. 200–202)

- ↑ "The basilica dates back to the year 900 of the Christian era [...]. ("La basilica risale all' anno XC dell'éra cristiana [...].")Paolo Rotta (1891, p. 114)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Saverio Almini (2006, p. 150)

- ↑ Frank Zöllner (2017, p. 92, ch.III. Nouveau départ à Milan - 1483-1484)

- 1 2 Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 204)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 200)

- ↑ Frank Zöllner (2017, p. 92)

- ↑ Charles Nicholl (2006, p. 238)

- ↑ Serge Bramly (2019, p. 272)

- ↑ Serge Bramly (2019, p. 268)

- ↑ Serge Bramly (2019, p. 267)

- ↑ Pietro Marani & Edoardo Villata (1999, p. 127)

- 1 2 3 Frank Zöllner (2017, p. 356, Catalogue critique des peintures, XI)

- ↑ Rachel Billinge; Luke Syson; Marika Spring (2011). "Altered Angels : Two panels from the Immaculate Conception Altarpiece once in San Francesco Grande, Milan" (PDF). National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 32: 57–77.

- 1 2 3 4 Pietro Marani & Edoardo Villata (1999, p. 133)

- ↑ Pietro Marani & Edoardo Villata (1999, p. 129)

- ↑ Charles Nicholl (2006, p. 501)

- 1 2 3 Paolo Rotta (1891, pp. 114–115)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Damiano Iacobone (2015, p. 87)

- 1 2 3 Aristide Calderini (1940, pp. 209–210)

- 1 2 Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 209 and 225)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 228)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 221)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 224)

- ↑ blog.urbanfile.org (2016)

- ↑ Paolo Rotta (1891, pp. 113 and seq.)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, pp. 197–208, ch.I. A hint by Bonaventura Castiglione et ch.II. A description of the Church of S. Francesco Grande by Giacomo Filippo Besta)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, pp. 198–199, planche 1)

- ↑ Damiano Iacobone (2015, p. 87 et seq.)

- ↑ storiedimilano (2016)

- ↑ "La facciata antica, in pietra cotta rossa e 5 finestre e torri e crocette con tre porte e la media rotonda e di molta fattura avente al di fuori sepulcri et statuae." Paolo Rotta (1891, p. 114)

- ↑ blog.urbanfile.org (2016) and as shown by Giovanni Battista Bonacina's depiction of the church in his 1640 view of Milan.

- ↑ "L'interno poi a tre navi ornata in amendue i lati di dodici archi e di tante altre colonne in pietra con capitelli corinzii ma rozzi fino al numero di 18 con otto finestre per parte". Paolo Rotta (1891, p. 114)

- 1 2 Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 210)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 225)

- ↑ "il Choro vuoto, grande, bello e vistoso, adornato con stucchi et molto chiaro per la largezza delle finestre" Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 210)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 211)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 215)

- ↑ Patrick Boucheron (1998, p. 146)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Patrick Boucheron (1998, p. 148)

- ↑ Eugenio Chiarini (Enciclopedia Dantesca) (1970). "Este, Beatrice d'".

- ↑ Michele Caffi (1869). La tomba del Carmagnola (in Italian). Tipografia Galileiana. pp. 4 and 5.

- ↑ Girolamo Arnaldi (2003). Liber Largitorius : études d'histoire médiévale offertes à Pierre Toubert par ses élèves (in French). Genève: Droz. pp. 145–150. ISBN 9782600009072. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ↑ Aldo Galli (November 15, 2014). "Il monumento Borromeo già in San Francesco Grande a Milano nel corpo della scultura lombarda". Modernamente Antichi (in Italian). Rome: Viella: 193–216. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ↑ Giorgio Vasari; Léopold Leclanché; Philippe-Auguste Jeanron; Léopold Leclanché (1840). Le Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (in Italian). Vol. 4. Paris. p. 92.

- ↑ National Gallery of Art (2019). "Vincenzo Foppa - Saint Anthony of Padua". nga.gov. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ↑ The Denver Art Museum. "Madonna and Child with Saints". www.denverartmuseum.org. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ↑ The Denver Art Museum. "Opere dalla diocesi". chiostrisanteustorgio.it (in Italian). Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- 1 2 Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 219)

- ↑ Aristide Calderini (1940, p. 220)

Appendices

Bibliography

Books

- Alberto Angela (2018). "L'époque de Ludovic le More 1488-1498". Le regard de la Joconde : La Renaissance et Léonard de Vinci racontés par un tableau (in Italian). Translated by Sophie Bajard. Paris: Payot & Rivages. pp. 153–161. ISBN 978-2-2289-2175-6.

- Gerolamo Biscaro (1910). La commissione della 'Vergine delle roccie' a Leonardo da Vinci secondo i documenti originali 25 aprile 1483 (in Italian). Milano: Tip. L.F. Cogliati. OCLC 27348576. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- Louis Baunard (1899). "L'église de Milan et les catéchèses d'Ambroise". Histoire de Saint Ambroise (in French). Paris: Librairie Poussielgue. pp. 53–70. OCLC 902119552.

- Patrick Boucheron (1998). "À l'ombre de la cathédrale : le pince fondateur et bienfaiteur d'églises". Le pouvoir de bâtir : Urbanisme et politique édilitaire à Milan (XIVe-XVe siècles) (PDF). La faveur et la ferveur : La multiplication des acteurs d'une politique de bienfaisance (in French). Rome, Palais Farnèse: Publications de l'École française de Rome. pp. 145–150. OCLC 1047929216. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Serge Bramly (2019). "La plume et le canif". Léonard de Vinci : Une biographie (in French). Paris: Jean-Claude Lattès. pp. 249–310. ISBN 978-2-7096-6323-6.

- Aristide Calderini (September 1940). "Documenti Inediti Per La Storia Della Chiesa Di S. Francesco Grande In Milano". Aevum (in Italian) (2–3): 197–230. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- Damiano Iacobone (2015). "Piazza Sant'Ambrogio tra XIX e XX secolo". Il volto di una piazza : Indagini archeologiche per la realizzazione del parcheggio in Piazza Sant'Ambrogio a Milano (in Italian). Anna Maria Fedeli and Carla Pagani. Milan: Edizioni ET Milano. pp. 87–95. ISBN 978-88-86752-65-7. OCLC 935317944.

- Pietro Marani; Edoardo Villata (1999). Leonardo, una carriera di pittore [Léonard de Vinci : Une carrière de peintre] (in French). Translated by Anne Guglielmetti. Arles ; Milan: Actes Sud ; Motta. pp. 126–148. ISBN 2-7427-2409-5.

- Charles Nicholl (2006). Leonardo da Vinci, the flights of the minds. Translated by Christine Piot. Arles: Actes Sud. pp. 238–244. ISBN 2-7427-6237-X.

- Marco Sannazaro; et al. (Anna Maria Fedeli et Carla Pagani) (2015). "Il sepolcreto tardoantico-altomedievale e la necropoli ad martyres". Il volto di una piazza : Indagini archeologiche per la realizzazione del parcheggio in Piazza Sant'Ambrogio a Milano (in Italian). Milan: Edizioni ET Milano. pp. 36–50. ISBN 978-88-86752-65-7. OCLC 935317944.

- Paolo Rotta (1891). "Basilica dei Santi Naborí e Felice detta di San Francesco". Passeggiate storiche, ossia Le chiese di Milano dalla loro origine fino al presente (in Italian). Milano. pp. 113–115. OCLC 77322953. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Frank Zöllner (2017). Léonard de Vinci, 1452-1519 : Tout l'œuvre peint (in French). Köln: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-6296-6.

Articles

- Aristide Calderini. "Indagini intorno alla chiesa di S. Francesco Grande in Milano". Rendiconti dell'Istituto Lombardo di Scienze (in Italian). 7: 103–132.

- Larry Keith; Ashok Roy; Rachel Morrison; Peter Schade (2011). "Leonardo da Vinci's Virgin of the Rocks : Treatment, Technique and Display" (PDF). National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 32: 32–56. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- Saverio Almini (July 2006). "Le fondazioni degli ordini religiosi VIII-XVIII secolo" (PDF). Le Istituzioni Storiche del Territorio Lombardo (in Italian). Retrieved June 18, 2019.

Related articles

External links

- blog.urbanfile.org (2016). "Milano - Porta Vercellina – San Francesco Grande, uno scrigno di capolavori sparito per sempre" (in Italian). Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- storiedimilano.blogspot.com (November 16, 2016). "Storie di Milano - La chiesa di San Francesco Grande". it. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

.jpg.webp)