Climate change in Nigeria is evident from temperature increase, rainfall variability (increasing in coastal areas and decline in continental areas). It is also reflected in drought, desertification, rising sea levels, erosion, floods, thunderstorms, bush fires, landslides, land degradation, more frequent, extreme weather conditions and loss of biodiversity.[1] All of which continues to negatively affect human and animal life and also the ecosystems in Nigeria.[2] Although, depending on the location, regions experience climate change with significant higher temperatures during the dry seasons while rainfalls during rainy seasons help keep the temperature at milder levels. The effects of climate change prompted the World Meteorological Organization, in its 40th Executive Council 1988, to establish a new international scientific assessment panel to be called the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).[3] The 2007 IPCC's fourth and final Assessment Report (AR4) revealed that there is a considerable threat of climate change that requires urgent global attention.[3] The report further attributed the present global warming to largely anthropogenic practices. The Earth is almost at a point of no return as it faces environmental threats which include atmospheric and marine pollution, global warming, ozone depletion, the dangers of pollution by nuclear and other hazardous substances, and the extinction of various wildlife species.[4]

The escalation of climate variability in Nigeria has led to heightened and irregular rainfall patterns, exacerbating land degradation and resulting in more severe floods and erosion. As one of the top ten most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change, Nigeria has experienced a worsening of these environmental challenges. By 2009, approximately 6,000 gullies had emerged, causing destruction to infrastructure in both rural and urban areas of the country.[5]

There are few comprehensive reports that provide useful evidence of various impacts of climate change experienced in Nigeria today.[6][7] The vast majority of the literature provides evidence of climate change holistically and this does not help in providing sustainable solutions to the impacts experienced.[8][9] However, the agricultural sector should be given more focus especially the existence in diverse regions where large farming is not dominantly practiced. More deliberations should concentrate on other mitigation and adaptation measures in literature which often takes the form of recommendations, rather than examples of what has already been achieved.[10]

This topical discourse is likely due to the need for much greater implementation of mitigation and adaption measures in ensuring Nigeria produce more food all through the year round to feed the growing population. In addition, while there is some discussion about necessary capacity building at the individual, group and community level to engage in climate change responses, there is also more or less attention given to higher levels of capacity building at the state and national level.[10]

The associated challenges of climate change are not the same across all geographical areas of the country. This is because of the two precipitation regimes: high precipitation in parts of the Southeast and Southwest and low in the Northern Region. These regimes can result in aridity, desertification and drought in the north; erosion and flooding in the south and other regions,[11][12][13] Neglected climate change actions is the issue of recycling of PET Bottles particularly in the locally. The use of polyethylene terephthalate also known as PET or PETE (a plastic resin materials used for making packaging materials such as bottles and food containers) is increasingly becoming paramount among manufacturers, as they used these PET bottles to package their products because it (PET) is an excellent barrier material with high strength, thermostability and transparency. Nigeria currently has no standard policy to regulate plastic waste; several efforts including legislations and contracts awarded for the installation of plastic waste recycling plants across the country have been marred by corruption and lack of political will by the government.[14]

.jpg.webp)

Greenhouse gas emissions

In the year 2018, Nigeria's total greenhouse gas emissions was 336 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), which is less than 1 percent of global emissions.[15]: 1 This means that emissions per person per year is less than 2 tons, compared to the global average of over 6 tons.[16][17] These greenhouse gases, mainly carbon dioxide and methane are mostly generated from oil and gas production, land-use change, forestry, agriculture and fugitive emissions.[16][18] The economy is very dependent on oil production, so it may be hard to reach the target of net zero emissions by 2060.[15]

There are factors that promote greenhouse gas emissions. It is recorded that the transportation sector is responsible for 28% of the greenhouse gas emissions in 2021. The main source of these emissions is the combustion of fossil fuels, such as gasoline and diesel, in cars. The production of electricity, which makes up 25% of emissions, also adds to the emissions of greenhouse gases.[19] The industrial sector, responsible for 23% of emissions, mostly employs fossil fuels for chemical reactions and energy production. 13% of emissions, including heat and refrigeration in buildings, come from the commercial and residential sectors. Livestock and agricultural soils are the main sources of agriculture, which contributes 10% of emissions. 12% of emissions are offset by land use and forestry, since managed forests have been a net sink for emissions since 1990.[20]

In order to warm the biosphere to a temperature suitable for human habitation, greenhouse gases (GHGs) absorb and reemit a considerable portion of the 161 W m−2, making them indispensable for life on Earth. Global surface temperatures have recently increased due to biosphere warming caused by rising GHG concentrations in the atmosphere. Since 1750, agriculture has produced 10–14% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions worldwide each year, directly influencing five of the main radiative sources of climate forcing. More greenhouse gases are impacted by agriculture than not.[21]

Impacts on the natural environment

Temperature and weather

Current climate

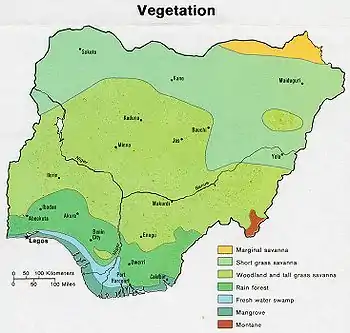

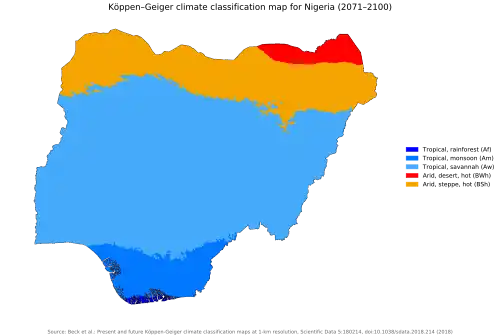

Nigeria has three different climate zones: a Sahelian hot and semi-arid climate in the north, a tropical monsoon climate in the south, and a tropical savannah environment in the center regions.[22] While the core regions only get one rainy and one dry season, the southern parts see heavy rainfall from March to October. There is a lot of annual variance in the north, which causes droughts and flooding. The mean annual temperature of the country varies greatly between coastal and interior regions; the plateau has a mean temperature between 21°C and 27°C, while the interior lowlands typically see temperatures above 27°C. There is variation in rainfall from April to October, and the average annual temperature is 26.9°C.[23]

Nigeria has a tropical climate with two seasons: (wet and dry). Inland areas especially those in the northeast, experience the greatest fluctuations in temperatures as before the outset of rains, temperatures sometimes rise as high as 44 °C and drops to 6 °C between December and February. In Maiduguri, the maximum temperature may rise to 38 °C in April and May while in the same season frosts might occur at night.[24]

For example, in Lagos, the average high is 31 °C and low is 23 °C in January and 28 °C and 23 °C in June. The southeast regions especially located around the coast like Bonny Island (south of Port Harcourt), east of Calabar receive the highest amount of annual rainfalls of around 4,000 millimeters.[24][25]

Changes in climate

Climate change in Nigeria is shifting climate regions. The desert region in the North is receding North, steppe region in the North is set to expand southwards, the tropical savanna climate is expanding, and tropical monsoon regions in the South are moving northwards, replacing tropical rainforest.[25]

Increase in temperature

The effects of the temperature increase are unbearable for residents, particularly those living in communities hosting gas flare plants. The increase in temperature causes bodily rashes, among other things, and hinders the growth of food crops. The availability of nutrients, plant and root growth, and seed germination are all affected by soil temperature. High temperatures hinder a plant's regular growth, photosynthesis, and flowering since they do not improve plant physiology. [26]

Rising sea levels, fluctuating rainfall, higher temperatures, flooding, droughts, desertification, land degradation, and an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events are all contributing factors to Nigeria's changing climate. Forecasts indicate that this will continue to cause significant runoffs and flooding in several locations. Forecasts of the climate indicate that every biological zone will see a notable rise in temperature. Although there is some literature showing the effects of and solutions to climate change, the majority of it concentrates on the farming industry and specific farming locales. Increased focus must be paid to capacity building at the state and federal levels, as well as increased implementation of mitigation and adaptation measures.[27]

The Nigerian Meteorological Service (NiMet) issues a warning about rising temperatures, especially in the north, which can lead to an increase in hospital admissions for elderly patients, neonates, and children due to heatstroke, cardiovascular, respiratory, and cerebrovascular illnesses.[28]

Due to climate change, Northern Nigeria is seeing greater heatwaves and lengthier, more erratic rainfall. New problems such extreme droughts, floods, deforestation, pollution, and food shortages have resulted from this. Daily living has been impacted by climate change, and many individuals have had to modify their behavior to cope. Due to the heat, some students have missed class or experienced health issues. Others have fallen behind in their academics and suffered from migraines. The extra strain might have a disastrous effect on Nigeria's underfunded, overcrowded, and fiercely competitive educational system.[29]

According to historical data from 2012 to 2019 used to examine trends in temperature and rainfall in Agbani, Enugu State. The climate from 2020 to 2050 was forecasted via Trend Regression analysis to be wetter and hotter. In 2018 and 2015 there were the most and lowest amounts of rainfall, respectively. The months of January, July, and March had the highest monthly mean rainfall, respectively. Also, between 2020 and 2050, farmers expect a wetter environment.[30]

Ecosystems

An ecosystem is a complex and interconnected community of living organisms, their physical environment, and the interactions between them.[31][32] It encompasses both biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) components, functioning as a dynamic system where various species interact with one another and with their surroundings.[33][34] Ecosystems can vary in scale, from small microhabitats to large biomes such as forests, oceans, and grasslands.

The concept of ecosystems was first introduced by the British ecologist Arthur Tansley in 1935, who defined it as "the whole system. including not only the organism-complex, but also the whole complex of physical factors forming what we call the environment".[35] This definition highlights the importance of considering both living organisms and their environment when studying ecosystems.

Ecosystems are characterized by the flow of energy and the cycling of nutrients. Energy enters an ecosystem through primary producers, such as plants or algae, which capture sunlight and convert it into chemical energy through photosynthesis.[36] This energy is then transferred to higher trophic levels as organisms feed on each other, forming food chains and food webs.

Ecosystems are sustained by the cycling of nutrients. Nutrients, such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus, are essential for the growth and survival of organisms. These elements are recycled within the ecosystem through various processes like decomposition, nutrient uptake by plants, and consumption by animals.[37] This recycling ensures a continuous supply of nutrients for the organisms within the ecosystem.

Ecosystems provide numerous ecological services that are vital for the well-being of both the natural world and human society. For instance, forests act as carbon sinks, absorbing and storing large amounts of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change.[38] Wetlands play a crucial role in water purification and flood control.[39] Coral reefs provide habitat for numerous marine species and act as natural barriers against storms.[40]

Ecosystems are facing numerous threats due to human activities, such as deforestation, pollution, climate change, and habitat destruction (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). These disturbances can disrupt the delicate balance of an ecosystem, leading to species extinction, loss of biodiversity, and the degradation of ecosystem services.

To better understand and manage ecosystems, scientists employ various approaches, including ecological modeling, field observations, and experimentation. These tools help researchers study the interactions between organisms, identify key ecological processes, and assess the impacts of human activities on ecosystems. Ecosystem management strategies aim to promote sustainable practices that maintain or restore the integrity and functioning of ecosystems.[41]

Years ago, Nigeria experienced climate change disaster which happened in the Northeastern region which is now Borno and Yobe states the territory along the southern part of Lake Chad dried up. Due to logging and over dependence on firewood for cooking, a greater part of Nigeria's Guinean forest-savanna mosaic region has been stripped of its vegetation cover. Similarly, the forest around Oyo State has been reduced to grassland.[42][43] The lack of sufficient cover trees and other vegetation can cause natural change, desertification, and soil breaking down, flooding, and extended ozone exhausting substances in the environment.[44]

Sea level rise and floods

In late August 2012, Nigeria was hit by the worst flooding ever experienced in 40 years. This affected 7 million people in communities across 33 states including kogi state. More than 2 million people out of the affected 7 million were driven from their homes by rising waters.[45][46]

Nigeria experienced another flooding caused by heavy seasonal rains in 2013 which brought further misery to a population that was still recovering from the 2012 fatal floods. Many mud-brick homes collapsed and families' belongings were ruined. Dug wells which are sources of potable water were also polluted. The states of Abia, Bauchi, Benue, Jigawa, Kebbi, Kano, Kogi and Zamfara were most affected by the floodwaters which lasted for 48 hours. The situation in Kaduna and Katsina was aggravated by the collapse of earth dams. According to the National Emergency Management Agency, more than 47,000 people were affected. This lesser number of people affected is attributed to the lessons of the 2012 floods which prepared the country for a better response.[47]

In Nigeria areas around the coastal regions are at risk of rising sea level. For example, the Niger Delta area is extremely vulnerable to flooding at a risk of rising sea level and a victim of extreme oil pollution. Climate change was the reason behind the flood that took place in southern Nigeria in 2012. The flood was responsible for the loss of houses, farms, farm produce, properties and lives. According to statistics released in 2014 by National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), about 5,000 houses and 60 homes were affected in a windstorm that occurred in four states in the south west region.[42]

Impacts

The country is likely to experience exacerbate floods, droughts, heat waves and hamper agricultural production in hotter and drier seasons.[48]

Health

NIMET has predicted an increased incidence of malaria due to climate change, and other diseases that will be higher in areas with temperatures ranging between 18 and 32 °C and with relative humidity above 60 percent.[48]

Economic

Agriculture

Agriculture remains the mainstay of the Nigerian economy in spite of oil as it employs two-thirds of the entire working population.[49][50][51] The sector is fraught with challenges as agricultural production is still mainly rainfall and subject to weather vagaries. Farmers find it hard to plan their operations due to unpredictable rainfall vagaries.[52] Increase in the total amount of rainfall and extreme temperature would have more of a negative effect on staple crops productivity. However, in northern states such as Borno, Yobe, Kaduna, Kano and Sokoto most crops might benefit economically. Crops such as millet, melon, sugarcane that are grown in the north will most likely benefit from extreme temperature.[53]

The sector is also plagued with:

- an outdated land tenure system that limits access to land (1.8 hectares or 4.4 acres per farming household)

- reduced irrigation development capacity (cropped land under irrigation less than one percent)

- lack of access to other agricultural improvements and support indicated by low adoption of technologies, limited access to fertilisers, inadequate storage facilities and limited market access.

- financial restrictions of limited access to credits; expensive farm inputs

All of these combined, have reduced agricultural productivity to, for example, average cereal production of 1.2 metric tons per hectare [0.48 long ton/acre; 0.54 short ton/acre]). This is coupled with high postharvest losses and wastage.[50]

Fisheries

The fishery sub-sector in Nigeria contributes about 3–4 percent to the country's annual GDP. It is also a key contributor to the nutritional requirements of the population as it constitutes about 50 percent of animal protein intake. The sector also provides income and employment for a substantial number of small traders and artisanal fishermen.[50] Over the past few years, capture fisheries have been declining and despite high potential Nigeria has in both fresh water and marine fisheries, domestic fish production still falls short of total demand. This has led to a high dependence on imports. To reduce importation dependence, aquaculture has been made one of the priority value chains targeted for development by the government. Climate change affects the characteristics and nature of water resources due to rising sea levels and extreme weather events. Increased salinity and shrinking lakes and rivers are also threats to the viability of inland fisheries.[52] Nigerians are impacted economically both directly and indirectly by the fishing industry, which is important to the nation's economy.[54][55]

The economic advantages and effects of fishing on the people of Nigeria include:

- Livelihoods and employment: those who reside in coastal and fishing villages, have job options in the fisheries sector.[56][57] It provides employment for fish processors, boat builders, producers of equipment, traders, and other ancillary businesses. The Nigerian Fisheries Statistical Bulletin estimates that approximately 3.2 million persons were working in the industry in 2019. Particularly in rural and coastal regions, these job options contribute to means of subsistence, income production, and the eradication of poverty.

- Food security and nutrition: The population's dietary and nutritional needs are mostly met by the fishing industry. Fish is a great source of minerals and animal protein.[58] It offers a reasonably priced and convenient source of nourishment, especially in communities close to waterbodies or coastal regions where fish is easily accessible.[59][60] Fish availability helps vulnerable communities fight hunger, improves nutrition, and increases food security.

- Trade and income generation: Both domestically and abroad, the fishing industry helps to generate income. Selling fish to neighborhood markets and processing businesses is how Nigerian fish sellers and fishermen make their living.[61] Nigeria exports a sizeable amount of fish products to its neighbors and other nations, which helps to promote global commerce and generate foreign currency.[62]

- Economic growth and GDP contribution: Nigeria's fisheries make a positive contribution to the country's overall economic growth and GDP.[63] Through the production of revenue, source of employment, and commerce, it improves the economy. The National Bureau of Statistics estimates that in 2020, the fisheries sector's share of agriculture's contribution to Nigerian GDP was 4.5 percent.[64][65]

- Auxiliary businesses and industries: The fishing industry supports a number of auxiliary businesses and industries, expanding economic potential.[66] Boat construction, the manufacture of fishing equipment, the packing and processing of fish, cold storage facilities, transportation, and retail companies are a few examples. These auxiliary businesses support entrepreneurship, the diversification of economic activity, and local economic growth.[67]

The fisheries industry suffers a number of difficulties and sustainability issues, such as overfishing, illicit fishing, insufficient infrastructure, restricted availability of credit and funding, and weak regulatory and governance frameworks.[68][69] The long-term economic advantages may be increased and the sector's contribution to the wellbeing of the Nigerian people can be ensured by addressing these issues through sustainable fisheries management methods and policies.

Forestry

Nigeria is endowed with variety of forest resources, from savannas in the north to rainforests in the south, and diverse species which fulfill a number of environmental functions. These include wildlife, medicinal plants and herbs, watershed protection, hydrological regime stabilization and carbon sequestration. Forests regulate global climate and serve as a major agent of carbon exchange in the atmosphere.[70] In Nigeria, natural forests have reduced drastically and its impacts on climate change are increasing. Erosion and excessive wind reduces the amount of forestry produce, such as wood and cane.[71] Forests are under significant pressure not only from climate change but also from increasing populations and greater demand for forest resources.[52]

The excessive exploitation of these forest resources is a source of concern as it is a threat to the economic, environmental and social wellbeing of Nigerians. Apart from providing a significant proportion of global timber and fuel, .

In Nigeria, forestry is important to both the economy and attempts to preserve the environment.[72][73][74]

Nigeria's woods may be generally divided into three different kinds based on their distribution and characteristics:

- Rainforests: Located in the southern region of the country, these forests are characterized by high rainfall, dense vegetation, and a wide variety of tree species. They include the freshwater swamp forest and the tropical lowland rainforest.

- Guinea savanna woodland: These savannas are found in the center of Nigeria and are distinguished by a mixture of trees and grasses. They serve as a transitional area between the southern rainforests.

Strengthening defences

To address the situation, Nigeria initiated the Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) in 2012. This project embraced progressive integrated methods centered around active community involvement. By its completion in 2022, NEWMAP successfully connected poverty reduction efforts with sustainable ecosystems and enhanced disaster-risk prevention. This comprehensive strategy has had a positive impact on the well-being and safety of over 12 million individuals across 23 states in Nigeria.

NEWMAP implemented various mechanisms to safeguard Nigerians from the potential impacts of future climate change. The project restored dozens of gully sites and built nearly 60 catchments to effectively control erosion. To enhance preparedness, warning and monitoring systems were put in place. Stormwater diversion plans were devised and solid waste management was improved to reduce the likelihood of flooding during heavy rainfall events. These efforts aimed at fortifying the nation against the adverse effects of climate change and enhancing resilience in the face of environmental challenges.

In order to assist farmers in managing droughts effectively, climate-smart agricultural innovations have been introduced, focusing on water conservation. These innovations include the widespread implementation of solar-powered drip irrigation systems and rainwater harvesting techniques. These measures aim to optimize water usage, allowing farmers to adapt to challenging climate conditions and ensure more sustainable agricultural practices during periods of water scarcity.[5]

Climate adaptation or mitigation

Climate Carbon mitigation is an issue for the world's economies as they work to combat climate change and advance environmental and socioeconomic sustainability.[75] However, for most of African countries, including Nigeria, the carbon footprint is low yet the effects of the climate crises is in the country is huge. The world's economy cannot abruptly quit using fossil fuels, since that would mean the end of the current way of life. Without the fossil fuel economy, materials for computers or smartphones, or the ability for online communications would end. Fossil fuels are necessary for all aspects of modern living, including food, clothing, shelter, water, entertainment, and others.

Adapting to the effects of the climate crises falls on the whole population, despite individuals in domestic settings not being a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions. Consequent disruptions, especially in areas like agriculture and health, cause ripple effects on human migration, gender inequality, food security and standards of living.[76]

The Great Green Wall

The Great Green Wall project was adopted by the African Union in 2007, initially conceived as a way to combat desertification in the Sahel region and hold back expansion of the Sahara desert by planting a wall of trees stretching across the entire Sahel. The current focus of the project is to create a mosaic of green and productive landscapes across North Africa by promoting water harvesting techniques, greenery protection, and improving indigenous land use techniques.[77] The ongoing goal of the project is to restore 100 million hectares (250 million acres) of degraded land and capture 250 million tonnes of carbon dioxide, and create 10 million jobs in the process all by 2030.

Policies and legislation

Nigeria ratified the Paris Agreement, an international deal aimed at tackling climate change, in 2017 and has pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2030 with the condition of 45% of international support.[78] Also, in demonstration of the country's seriousness in approaching climate action, President Muhammadu Buhari signed the country's climate change bill into law in November 2021.

Mitigation and adaptation policy

The IPCC[79] describes climate mitigation as the transition from the fossil fuel economy, where burning fossil fuels to produce energy and emissions to make things to an economy that produces zero emissions; that is to remove carbon emissions from every part of the economy, as fast as possible in order to prevent further global heating.

To mitigate the adverse effect of climate change, not only did Nigeria sign the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions, in its national climate pledge, it also committed to attempting to eliminate gas flaring by 2030 and has devised a National Forest Policy. Effort is also been made to stimulate the adoption of climate-smart agriculture and the planting of trees.[80]

The increasing vulnerability to extreme climatic change in Nigeria is exacerbated by accelerated urbanization, which is pushing more people into capital cities and other regions. This expansion is encroaching on flood plains and coastal areas, heightening the risks of coastal floods. To address these challenges, promoting planned human settlements and intensive urban infrastructure development is crucial. Additionally, the government must implement policy interventions and allocate increased funding for climate-related projects to protect properties and lives in susceptible areas and build resilience to climate change impacts.

To enhance adaptation to climate-related disasters in Nigeria, a comprehensive and structured plan for climate change adaptation must include coastal states and flood plains. The implementation of national initiatives like the Great Green Wall and the Climate Change Act is essential to combat desertification, food shortages, and climate change impacts. Proper funding and implementation of the Nigeria Climate Change Commission are vital to provide strong institutional support for vulnerable states in the country. Prioritizing these measures will improve Nigeria's resilience and capacity to cope with climate-related challenges and foster sustainable development.

- monitoring to evaluate species and ecosystems stability from climate change perspective.[81]

Nigeria Energy Transition Plan

In 2021 during COP 26, the then Nigerian President, President Muhammadu Buhari, unveiled the Nigerian Energy Transition Plan as part of country's commitment towards achieving NET Zero by the year 2060. The plan included a timeline and framework for achieving reduced emissions in certain sector of the country such as Oil and Gas, Cooking, Transport and Industry and Power. This is in a bid to help slow down the change in climate.[82][83] Nigeria's Energy Transition Plan (ETP) is a long-term strategy to decarbonize the country's energy sector and achieve net-zero emissions by 2060. The ETP was launched in August 2022 and is based on a data-driven approach that identifies the most cost-effective pathways to decarbonization.[84]

The ETP key sector:

- Power: The ETP aims to increase the share of renewable energy in the power sector to 30% by 2030 and 60% by 2060. This will be achieved through the deployment of solar, wind, and hydro power projects, as well as the development of a national grid.

- Cooking: The ETP aims to transition to clean cooking fuels by 2030. This will be achieved through the promotion of solar-powered cooking stoves and the development of a national gas grid.

- Industry: The ETP aims to decarbonize the industrial sector by 2060. This will be achieved through the adoption of energy-efficient technologies and the use of renewable energy sources.

- Transportation: The ETP aims to electrify the transportation sector by 2060. This will be achieved through the deployment of electric vehicles and the development of a national charging infrastructure.

The Nigeria ETP is a comprehensive and ambitious plan that has the potential to transform the country's energy sector. The plan in its efforts to address climate; change and achieve sustainable development.[85] The plan aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060. Gas will play a critical role as a transition fuel in the power and cooking sectors. The plan creates significant investment opportunities in the solar, wind, and hydrogen sectors. The plan is expected to create up to 840,000 jobs by 2060.

International cooperation

The UNDP is committed to supporting Nigeria and a UNDP-NDC Support Programme is already fully in motion. One of their goals is having increased engagement with the government and private sector.[48]

Public perception

A study of students at University of Jos, found that 59.7 percent of respondents had good knowledge about climate change, and understood its connection to issues like fossil fuel, pollution, deforestation and urbanization.[86]

While the academic community are informed about climate change and its effects, considering the amount of research conducted on the subject, less educated communities and those in rural areas have not regularly demonstrated climate change knowledge. A survey of 1000 people in rural communities in southwestern Nigeria found that many members had superstitions about climate change, and that respondents had poor knowledge about the causes and effects.[87] Some of the challenges with the non-specialist communities include lack of contextual information about climate change, language communication barrier in the local language.

See also

References

- ↑ O.A., Olaniyi; I.O., Olutimehin; O.A., Funmilayo (2019). "Review of Climate Change and Its effect on Nigeria Ecosystem". International Journal of Rural Development, Environment and Health Research. 3 (3): 92–100. doi:10.22161/ijreh.3.3.3.

- ↑ Dada, Abdullahi Aliyu; Muhammad, Umar (2014-12-29). "Climate Change Education Curriculum for Nigeria Tertiary Education System". Sokoto Educational Review. 15 (2): 119–126. doi:10.35386/ser.v15i2.175. ISSN 2636-5367.

- 1 2 Ogele, Eziho Promise (2020-09-30). "Battle on the Ballot: Trends of Electoral Violence and Human Security in Nigeria, 1964-2019". Journal of Social and Political Sciences. 3 (3). doi:10.31014/aior.1991.03.03.221. ISSN 2615-3718. S2CID 225018841.

- ↑ Bunyavanich, Supinda; Landrigan, Christopher P.; McMichael, Anthony J.; Epstein, Paul R. (January 2003). <0044:tiocco>2.0.co;2 "The Impact of Climate Change on Child Health". Ambulatory Pediatrics. 3 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0044:tiocco>2.0.co;2. ISSN 1530-1567. PMID 12540254.

- 1 2 "Land, soil and climate change: How Nigeria is enhancing climate resilience to save the future of its people". World Bank. Retrieved 2023-07-25.

- ↑ Maddison, David (2007-11-08). "The Perception Of And Adaptation To Climate Change In Africa". Policy Research Working Papers. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-4308. hdl:10986/7507. ISSN 1813-9450. S2CID 51799741.

- ↑ Labatt, Sonia; White, Rodney R., eds. (2012-01-02). Carbon Finance. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119202134. ISBN 978-0-471-79467-7. S2CID 237683140.

- ↑ Ataro, Ufuoma (2021-05-06). "As climate change hits Nigeria, small scale women farmers count losses". Premium Times Nigeria. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ "African Union Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan | Webber Wentzel". www.webberwentzel.com. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- 1 2 Haider, H. "Climate Change in Nigeria: Impacts and Responses". GOV.UK. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under an Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under an Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright. - ↑ Kenar, Nihal; Ketenoğlu, Osman (2016-09-01). "The phytosociology of Melendiz Mountain in the Cappadocian part of Central Anatolia (Niğde, Turkey)". Phytocoenologia. 46 (2): 141–183. doi:10.1127/phyto/2016/0065. ISSN 0340-269X.

- ↑ Akande, Adeoluwa; Costa, Ana Cristina; Mateu, Jorge; Henriques, Roberto (2017). "Geospatial Analysis of Extreme Weather Events in Nigeria (1985–2015) Using Self-Organizing Maps". Advances in Meteorology. 2017: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2017/8576150. hdl:10362/34214. ISSN 1687-9309.

- ↑ Onah, Nkechi G.; Alphonsus, N. Ali; Ekenedilichukwu, Eze (2016-11-01). "Mitigating Climate Change in Nigeria: African Traditional Religious Values in Focus". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 7 (6): 299. doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n6p299.

- ↑ "Nigerians Fighting Climate Change Through Plastic Recycling – The Whistler Newspaper". thewhistler.ng. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- 1 2 Department of Climate Change, Federal Ministry of Environment, Nigeria (November 2021). 2050 Long-Term Vision for Nigeria: Towards the Development of Nigeria's Long-Term Low Emissions Development Strategy (LT-LEDS) (PDF) (Report). Government of Nigeria.

- 1 2 Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2020-06-11). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ↑ Ge, Mengpin; Friedrich, Johannes; Vigna, Leandro (2020-02-06). "4 Charts Explain Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Countries and Sectors". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ↑ "The Carbon Brief Profile: Nigeria". Carbon Brief. 2020-08-21. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ↑ Ritchie, Hannah; Rosado, Pablo; Roser, Max (2023-09-28). "Greenhouse gas emissions". Our World in Data.

- ↑ "Greenhouse gas | Definition, Emissions, & Greenhouse Effect | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-10-16. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "Greenhouse Gas - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "Weather in Nigeria". www.timeanddate.com. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- 1 2 "Nigeria Weather". 2011-03-26. Archived from the original on 2011-03-26. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- 1 2 "Nigeria: Climate of Nigeria". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ↑ Chukwuka, K. S.; Alimba, C. G.; Ataguba, G. A.; & Jimoh, W. A. (2018). "The impacts of petroleum production on terrestrial fauna and flora in the oil-producing region of Nigeria". In The Political Ecology of Oil and Gas Activities in the Nigerian Aquatic Ecosystem (pp. 125-142). Academic Press.

- ↑ "Climate change in Nigeria: Impacts and responses | PreventionWeb". www.preventionweb.net. 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "Addressing rising temperatures in Northern Nigeria - Daily Trust". dailytrust.com. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ Akanbi, Abdulganiyu Abdulrahman (2023-06-15). "Degrees of heat: Northern Nigeria students wilt in climate extremes". African Arguments. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "Climate change in Nigeria: Impacts and responses | PreventionWeb". www.preventionweb.net. 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ Jeronen, Eila (2019), "Ecology and Ecosystem: Sustainability", Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-02006-4_904-1, ISBN 978-3-030-02006-4

- ↑ Price, Peter W. (April 1973). "Ecology Ecology: The Experimental Analysis of Distribution and Abundance Charles J. Krebs". BioScience. 23 (4): 264. doi:10.2307/1296598. ISSN 0006-3568. JSTOR 1296598.

- ↑ Jones, Clive G.; Gutiérrez, Jorge L.; Byers, James E.; Crooks, Jeffrey A.; Lambrinos, John G.; Talley, Theresa S. (2010-10-15). "A framework for understanding physical ecosystem engineering by organisms". Oikos. 119 (12): 1862–1869. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.18782.x. ISSN 0030-1299.

- ↑ Lowrance, Richard (1998), "Riparian Forest Ecosystems as Filters for Nonpoint-Source Pollution", Successes, Limitations, and Frontiers in Ecosystem Science, New York, NY: Springer New York, pp. 113–141, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1724-4_5, ISBN 978-0-387-98475-9, retrieved 2023-06-08

- ↑ Tansley, A. G. (2017-12-31), ""The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms" (1935)", The Future of Nature, Yale University Press, pp. 220–232, doi:10.12987/9780300188479-021, ISBN 9780300188479, S2CID 246143639, retrieved 2023-06-01

- ↑ Odum, Eugene P. (1969-04-18). "The Strategy of Ecosystem Development". Science. 164 (3877): 262–270. Bibcode:1969Sci...164..262O. doi:10.1126/science.164.3877.262. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 5776636. S2CID 3842438.

- ↑ Vitousek, Peter M.; Mooney, Harold A.; Lubchenco, Jane; Melillo, Jerry M. (1997-07-25). "Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems". Science. 277 (5325): 494–499. doi:10.1126/science.277.5325.494. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ Bonan, Gordon B. (2008-06-13). "Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests". Science. 320 (5882): 1444–1449. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1444B. doi:10.1126/science.1155121. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18556546. S2CID 45466312.

- ↑ Stefanakis, Alexandros (2019-12-06). "The Role of Constructed Wetlands as Green Infrastructure for Sustainable Urban Water Management". Sustainability. 11 (24): 6981. doi:10.3390/su11246981. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ↑ Narayan, Siddharth; Beck, Michael W.; Reguero, Borja G.; Losada, Iñigo J.; van Wesenbeeck, Bregje; Pontee, Nigel; Sanchirico, James N.; Ingram, Jane Carter; Lange, Glenn-Marie; Burks-Copes, Kelly A. (2016-05-02). "The Effectiveness, Costs and Coastal Protection Benefits of Natural and Nature-Based Defences". PLOS ONE. 11 (5): e0154735. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1154735N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154735. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4852949. PMID 27135247.

- ↑ Frissell, Christopher A.; Bayles, David (April 1996). "Ecosystem Management and the Conservation of Aquatic Biodwersity and Ecological Integrity". Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 32 (2): 229–240. Bibcode:1996JAWRA..32..229F. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.1996.tb03447.x. ISSN 1093-474X.

- 1 2 Beyioku, Jumoke (2016-09-19). "Climate change in Nigeria: A brief review of causes, effects and solution". Federal Ministry of Information and Culture. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ↑ "About Oyo State – Oyo State Government". Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ "deforestation effect on the ecosystem - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ "Red Cross braces for flooding in Nigeria - IFRC". www.ifrc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ "Urgent needs continue two months after Nigeria's worst flooding in 40 years - IFRC". www.ifrc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ "Lessons of 2012 inform Red Cross response as new floods hit Nigeria - IFRC". www.ifrc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- 1 2 3 "Nigeria must lead on climate change". UNDP. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ↑ Shiru, Mohammed; Shahid, Shamsuddin; Alias, Noraliani; Chung, Eun-Sung (2018-03-19). "Trend Analysis of Droughts during Crop Growing Seasons of Nigeria". Sustainability. 10 (3): 871. doi:10.3390/su10030871. ISSN 2071-1050.

- 1 2 3 "Nigeria at a glance | FAO in Nigeria | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org.

- ↑ Onwutuebe, Chidiebere J. (2019). "Patriarchy and Women Vulnerability to Adverse Climate Change in Nigeria". SAGE Open. 9 (1): 215824401982591. doi:10.1177/2158244019825914. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 150324364.

- 1 2 3 Onyeneke, Robert Ugochukwu; Nwajiuba, Chinedum Uzoma; Tegler, Brent; Nwajiuba, Chinyere Augusta (2020), "Evidence-Based Policy Development: National Adaptation Strategy and Plan of Action on Climate Change for Nigeria (NASPA-CCN)", African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–18, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_125-1, ISBN 978-3-030-42091-8

- ↑ Ajetomobi, Joshua (2015). "The potential impact of climate change on Nigerian agriculture". International Food Policy Research Institute. Archived from the original on 2018-08-14. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ↑ Allison, Edward H.; Perry, Allison L.; Badjeck, Marie-Caroline; Neil Adger, W.; Brown, Katrina; Conway, Declan; Halls, Ashley S.; Pilling, Graham M.; Reynolds, John D.; Andrew, Neil L.; Dulvy, Nicholas K. (June 2009). "Vulnerability of national economies to the impacts of climate change on fisheries". Fish and Fisheries. 10 (2): 173–196. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00310.x. ISSN 1467-2960.

- ↑ Ghisu, Paolo; Gueye, Moustapha Kamal (2009), "Climate Change and Fisheries", International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, Geneva, doi:10.7215/nr_in_20100114

- ↑ Making every blade count. [Ottawa]: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2008. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.61957.

- ↑ Reddy, Chinnamma (2020). Indo-Fijian Fishing Communities: Relationships with Taukei in Coastal Fisheries (Thesis). Victoria University of Wellington Library. doi:10.26686/wgtn.17144594.v1.

- ↑ ODİOKO, Edafe; BECER, Zehra Arzu (2022-06-30). "The Economic Analysis of The Nigerian Fisheries Sector: A Review". Journal of Anatolian Environmental and Animal Sciences. 7 (2): 216–226. doi:10.35229/jaes.1008836. ISSN 2548-0006. S2CID 247601992.

- ↑ Jobling, Malcolm (2007-03-24). "C. Lim, C. D. Webster (eds), Tilapia—Biology, Culture and Nutrition". Aquaculture International. 15 (2): 169–170. doi:10.1007/s10499-007-9095-0. ISSN 0967-6120. S2CID 19289580.

- ↑ Evely, Anna (2010-10-21). "Dead planet, living planet. Biodiversity and ecosystem restoration for sustainable development, a rapid response assessment. C. Nellemann, E. Corcoran (eds). 78: Birkland Trykkeri, Norway, 2010. ISBN 978-82-7701-083-0, 109pp". Land Degradation & Development. 23 (2): 200. doi:10.1002/ldr.1054. ISSN 1085-3278.

- ↑ Nyiawung, Richard A.; Bennett, Nathan J.; Loring, Philip A. (2023-02-22). "Understanding change, complexities, and governability challenges in small-scale fisheries: a case study of Limbe, Cameroon, Central Africa". Maritime Studies. 22 (1): 7. doi:10.1007/s40152-023-00296-3. ISSN 1872-7859. PMC 9944802. PMID 36846087.

- ↑ Diebold, William; Schmidheiny, Stephen (1992). "Changing Course: A Global Business Perspective on Development and the Environment". Foreign Affairs. 71 (4): 202. doi:10.2307/20045337. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20045337.

- ↑ Kütting, Gabriela (July 2004). "Standards and Global Trade: A Voice for Africa edited by John S. Wilson and Victor O. Abiola (2003). (Publisher: The World Bank)". World Trade Review. 3 (2): 329–330. doi:10.1017/s1474745604211909. ISSN 1474-7456. S2CID 152742658. [Book review].

- ↑ Balana, Bedru B.; Oyeyemi, Motunrayo A.; Ogunniyi, Adebayo I.; Fasoranti, Adetunji; Edeh, Hyacinth; Aiki, Joel; Andam, Kwaw S. (December 2020). "The effects of COVID-19 policies on livelihoods and food security of smallholder farm households in Nigeria: Descriptive results from a phone survey". IFPRI Discussion Papers. Washington, D. C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) (1979). doi:10.2499/p15738coll2.134179. OCLC 1228055741. S2CID 234543171.

- ↑ Cervigni, Raffaello; Rogers, John Allen; Henrion, Max, eds. (2013-05-29). Low-Carbon Development. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-9925-5. hdl:10986/15812. ISBN 978-0-8213-9925-5.

- ↑ Parkes, Margot (2006-08-15). "Personal Commentaries on "Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Health Synthesis—A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment"". EcoHealth. 3 (3): 136–140. doi:10.1007/s10393-006-0038-4. ISSN 1612-9202. S2CID 5844434.

- ↑ Gannon, Agnes (1994-01-01). "Rural tourism as a factor in rural community economic development for economies in transition". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2 (1–2): 51–60. doi:10.1080/09669589409510683. ISSN 0966-9582.

- ↑ Narayan, Deepa; Chambers, Robert; Shah, Meera K.; Petesch, Patti (January 2000). Crying Out for Change. The World Bank. doi:10.1596/0-1952-1602-4. ISBN 978-0-19-521602-8.

- ↑ Akegbejo-Samsons, Yemi (2022), "Aquaculture and Fisheries Production in Africa: Highlighting Potentials and Benefits for Food Security", Food Security for African Smallholder Farmers, Sustainability Sciences in Asia and Africa, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 171–190, doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6771-8_11, ISBN 978-981-16-6770-1, retrieved 2023-06-09

- ↑ "FOSA Country Report : Nigeria". www.fao.org.

- ↑ "The Political Economy of Climate Change and Climate Policy", Handbook on the Economics of Climate Change, Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 11, 2020, doi:10.4337/9780857939067.00006, ISBN 978-0-85793-906-7, S2CID 241516514, retrieved 2020-12-01

- ↑ Munasinghe, Mohan (September 1993). Environmental Economics and Sustainable Development. The World Bank. doi:10.1596/0-8213-2352-0. ISBN 978-0-8213-2352-6.

- ↑ Aubin, David (June 2008). "Branching Out, Digging In: Environmental Advocacy and Agenda Setting, Sarah B. Pralle, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2006, pp. xii, 279". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 41 (2): 494–495. doi:10.1017/s0008423908080554. ISSN 0008-4239. S2CID 154997071.

- ↑ Saravanan, Velayutham (2009-10-27). "Political Economy of the Recognition of Forest Rights Act, 2006". South Asia Research. 29 (3): 199–221. doi:10.1177/026272800902900301. ISSN 0262-7280. S2CID 153394354.

- ↑ Inah, Oliver I.; Abam, Fidelis I.; Nwankwojike, Bethrand N. (2022-12-12). "Exploring the CO2 emissions drivers in the Nigerian manufacturing sector through decomposition analysis and the potential of carbon tax (CAT) policy on CO2 mitigation". Future Business Journal. 8 (1): 61. doi:10.1186/s43093-022-00176-y. ISSN 2314-7210. PMC 9742040.

- ↑ "Climate change and weather: the Nigerian experience". The Sun Nigeria. 11 January 2023.

- ↑ Morrison, Jim. "The "Great Green Wall" Didn't Stop Desertification, but it Evolved Into Something That Might". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ↑ "The Carbon Brief Profile: Nigeria". Carbon Brief. 2020-08-21. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ↑ "IPCC — Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ↑ "The Carbon Brief Profile: Nigeria". 21 August 2020.

- ↑ "Nigeria | UNDP Climate Change Adaptation". www.adaptation-undp.org. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ↑ "Nigeria Energy Transition Plan". Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ↑ "Nigeria launches energy transition plan to tackle poverty, climate change". TheCable. 2022-08-24. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ↑ "Nigeria Energy Transition Plan". Government of Nigeria.

- ↑ "Nigeria's Energy Transition Office hosts Private Sector Roundtable". Sustainable Energy for All | SEforALL. 28 February 2023.

- ↑ Maton, S. M.; Awari, E. S.; Labiru, M. A.; Galadima, J. S.; Binbol, N. L.; Gyang, D. L.; Parah, E. Y.; Oche, C. Y. (2020-12-02). "Perception of global warming among undergraduates of the University of Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria". Journal of Meteorology and Climate Science. 18 (1): 41–48. ISSN 2006-7003.

- ↑ Asekun-Olarinmoye, Esther O.; Bamidele, James O.; Odu, Olusola O.; Olugbenga-Bello, Adenike I.; Abodurin, Olugbenga L.; Adebimpe, Wasiu O.; Oladele, Edward A.; Adeomi, Adeleye A.; Adeoye, Oluwatosin A.; Ojofeitimi, Ebenezer O. (2014). "Public perception of climate change and its impact on health and environment in rural southwestern Nigeria". Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine. 5: 1–10. doi:10.2147/RRTM.S53984. ISSN 1179-7282. PMC 7337145. PMID 32669887.