Food security is the availability of food in a country (or a geographic region) and the ability of individuals within that country (region) to access, afford, and source adequate foodstuff. The availability of food irrespective of class, gender or region is another element of food security. Similarly, household food security is considered to exist when all the members of a family, at all times, have access to enough food for an active, healthy life.[1] Individuals who are food secure do not live in hunger or fear of starvation.[2] Food insecurity, on the other hand, is defined as a situation of " limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways".[3] Food security incorporates a measure of resilience to future disruption or unavailability of critical food supply due to various risk factors including droughts, shipping disruptions, fuel shortages, economic instability, and wars.[4]

The four pillars of food security include: availability, access, utilization, and stability.[5] The concept of food security has evolved to recognize the centrality of agency and sustainability, along with the four other dimensions of availability, access, utilization, and stability. These six dimensions of food security are reinforced in conceptual and legal understandings of the right to food.[6][7] The 1996 World Summit on Food Security[8] declared that "food should not be used as an instrument for political and economic pressure".[9]

The International Monetary Fund cautioned in September 2022 that "the impact of increasing import costs for food and fertilizer for those extremely vulnerable to food insecurity will add $9 billion to their balance of payments pressures – in 2022 and 2023." This would deplete countries' foreign reserves as well as their capacity to pay for food and fertilizer imports."[10][11]

Definition

Food security is defined as "when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life" by the World Food Summit in 1996.[12][13]

Food insecurity, on the other hand, is defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a situation of " limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways".[3]

At the 1974 World Food Conference, the term "food security" was defined with an emphasis on supply; food security was defined as the "availability at all times of adequate, nourishing, diverse, balanced and moderate world food supplies of basic foodstuff to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset the fluctuations in production and prices".[14] Later definitions added demand and access issues to the definition. The first World Food Summit, held in 1996, stated that food security "exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life."[15][9]

Chronic (or permanent) food insecurity is defined as the long-term, persistent lack of adequate food.[16] In this case, households are constantly at risk of being unable to acquire food to meet the needs of all members. Chronic and transitory food insecurity are linked since the reoccurrence of transitory food security can make households more vulnerable to chronic food insecurity.[17]

As of 2015, the concept of food security has mostly focused on food calories rather than the quality and nutrition of food. The concept of nutrition security or nutritional security evolved as a broader concept. In 1995, it has been defined as "adequate nutritional status in terms of protein, energy, vitamins, and minerals for all household members at all times".[18]: 16 It is also related to the concepts of nutrition education and nutritional deficiency.

Measurement

Food security can be measured by calories to digest to intake per person per day, available on a household budget.[19][20] In general, the objective of food security indicators and measurements is to capture some or all of the main components of food security in terms of food availability, accessibility, and utilization/adequacy. While availability (production and supply) and utilization/adequacy (nutritional status/ anthropometric measurement) are easier to estimate and therefore, more popular, accessibility (the ability to acquire a sufficient quantity and quality of food) remains largely elusive.[21] The factors influencing household food accessibility are often context-specific.[22]

FAO has developed the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) as a universally applicable experience-based food security measurement scale derived from the scale used in the United States. Thanks to the establishment of a global reference scale and the procedure needed to calibrate measures obtained in different countries, it is possible to use the FIES to produce cross-country comparable estimates of the prevalence of food insecurity in the population.[23] Since 2015, the FIES has been adopted as the basis to compile one of the indicators included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) monitoring framework.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) collaborate every year to produce The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, or SOFI report (known as The State of Food Insecurity in the World until 2015).

The SOFI report measures chronic hunger (or undernourishment) using two main indicators, the Number of undernourished (NoU) and the Prevalence of undernourishment (PoU). Beginning in the early 2010s, FAO incorporated more complex metrics into its calculations, including estimates of food losses in retail distribution for each country and the volatility in agri-food systems. Since 2016, it also reports the Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity based on the FIES.

Several measurements have been developed to capture the access component of food security, with some notable examples developed by the USAID-funded Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) project.[22][24][25][26] These include:

- Household Food Insecurity Access Scale – measures the degree of food insecurity (inaccessibility) in the household in the previous month on a discrete ordinal scale.

- Household Dietary Diversity Scale – measures the number of different food groups consumed over a specific reference period (24hrs/48hrs/7days).

- Household Hunger Scale – measures the experience of household food deprivation based on a set of predictable reactions, captured through a survey and summarized in a scale.

- Coping Strategies Index (CSI) – assesses household behaviors and rates them based on a set of varied established behaviors on how households cope with food shortages. The methodology for this research is based on collecting data on a single question: "What do you do when you do not have enough food, and do not have enough money to buy food?"[27][28][29]

Prevalence of food insecurity

.svg.png.webp)

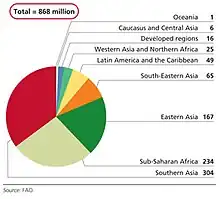

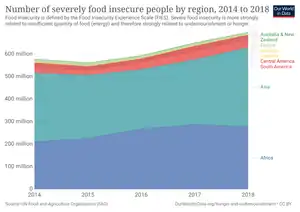

Close to 12 percent of the global population was severely food insecure in 2020, representing 928 million people – 148 million more than in 2019.[6] A variety of reasons lies behind the increase in hunger over the past few years. Slowdowns and downturns since the 2008-9 financial crisis have conspired to degrade social conditions, making undernourishment more prevalent. Structural imbalances and a lack of inclusive policies have combined with extreme weather events; altered environmental conditions; and the spread of pests and diseases, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, triggering stubborn cycles of poverty and hunger. In 2019, the high cost of healthy diets together with persistently high levels of income inequality put healthy diets out of reach for around 3 billion people, especially the poor, in every region of the world.[6]

Inequality in the distributions of assets, resources and income, compounded by the absence or scarcity of welfare provisions in the poorest of countries, is further undermining access to food. Nearly a tenth of the world population still lives on US$1.90 or less a day, with sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia the regions most affected.

High import and export dependence ratios are meanwhile making many countries more vulnerable to external shocks. In many low-income economies, debt has swollen to levels far exceeding GDP, eroding growth prospects.

Finally, there are increasing risks to institutional stability, persistent violence, and large-scale population relocation as a consequence of the conflicts. With the majority of them being hosted in developing nations, the number of displaced individuals between 2010 and 2018 increased by 70% between 2010 and 2018 to reach 70.8 million.[31]

Recent editions of the SOFI report (The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World) present evidence that the decades-long decline in hunger in the world, as measured by the number of undernourished (NoU), has ended. In the 2020 report, FAO used newly accessible data from China to revise the global NoU downwards to nearly 690 million, or 8.9 percent of the world population – but having recalculated the historic hunger series accordingly, it confirmed that the number of hungry people in the world, albeit lower than previously thought, had been slowly increasing since 2014. On broader measures, the SOFI report found that far more people suffered some form of food insecurity, with 3 billion or more unable to afford even the cheapest healthy diet.[32] Nearly 2.37 billion people did not have access to adequate food in 2020 – an increase of 320 million people compared to 2019.[33][34]

FAO's 2021 edition of The State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) further estimates that an additional 1 billion people (mostly in lower- and upper-middle-income countries) are at risk of not affording a healthy diet if a shock were to reduce their income by a third.[35]

The 2021 edition of the SOFI report estimated the hunger excess linked to the COVID-19 pandemic at 30 million people by the end of the decade[6] – FAO had earlier warned that even without the pandemic, the world was off track to achieve Zero Hunger or Goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals – it further found that already in the first year of the pandemic, the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) had increased 1.5 percentage points, reaching a level of around 9.9 percent. This is the mid-point of an estimate of 720 to 811 million people facing hunger in 2020 – as many as 161 million more than in 2019.[33][34] The number had jumped by some 446 million in Africa, 57 million in Asia, and about 14 million in Latin America and the Caribbean.[6]

At the global level, the prevalence of food insecurity at a moderate or severe level, and severe level only, is higher among women than men, magnified in rural areas.[36]

Vulnerable groups most affected

Children

Food insecurity in children can lead to developmental impairments and long term consequences such as weakened physical, intellectual and emotional development.[37]

By way of comparison, in one of the largest food producing countries in the world, the United States, approximately one out of six people are "food insecure", including 17 million children, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2009.[38] A 2012 study in the Journal of Applied Research on Children found that rates of food security varied significantly by race, class and education. In both kindergarten and third grade, 8% of the children were classified as food insecure, but only 5% of white children were food insecure, while 12% and 15% of black and Hispanic children were food insecure, respectively. In third grade, 13% of black and 11% of Hispanic children were food insecure compared to 5% of white children.[39][40]

Women

.jpg.webp)

Gender inequality both leads to and is a result of food insecurity. According to estimates, girls and women make up 60% of the world's chronically hungry and little progress has been made in ensuring the equal right to food for women enshrined in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.[41][42]

At the global level, the gender gap in the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity grew even larger in the year of COVID-19 pandemic. The 2021 SOFI report finds that in 2019 an estimated 29.9 percent of women aged between 15 and 49 years around the world were affected by anemia – now a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicator (2.2.3).[6]

The gap in food insecurity between men and women widened from 1.7 percentage points in 2019 to 4.3 percentage points in 2021.[43]

Women play key roles in maintaining all four pillars of food security: as food producers and agricultural entrepreneurs; as decision-makers for the food and nutritional security of their households and communities and as "managers" of the stability of food supplies in times of economic hardship.[36]

The gender gap in accessing food increased from 2018 to 2019, particularly at moderate or severe levels.[36]

History

Famines have been frequent in world history. Some have killed millions and substantially diminished the population of a large area. The most common causes have been drought and war, but the greatest famines in history were caused by economic policy.[45] One economic policy example of famine was the Holodomor (Great Famine) induced by the Soviet Union's communist economic policy resulting in 7–10 million deaths.[46]

In the late 20th century the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen observed that "there is no such thing as an apolitical food problem."[47] While drought and other naturally occurring events may trigger famine conditions, it is government action or inaction that determines its severity, and often even whether or not a famine will occur. The 20th century has examples of governments, such as Collectivization in the Soviet Union or the Great Leap Forward in the People's Republic of China undermining the food security of their nations. Mass starvation is frequently a weapon of war, as in the blockade of Germany in World War I and World War II, the Battle of the Atlantic, and the blockade of Japan during World War I and World War II and in the Hunger Plan enacted by Nazi Germany.

Pillars of food security

The WHO states that three pillars that determine food security: food availability, food access, and food use and misuse.[48] The FAO added a fourth pillar: the stability of the first three dimensions of food security over time.[2] In 2009, the World Summit on Food Security stated that the "four pillars of food security are availability, access, utilization, and stability".[5] Two additional pillars of food security were recommended in 2020 by the High-Level Panel of Experts for the Committee on World Food Security: agency and sustainability.[7]

Availability

Food availability relates to the supply of food through production, distribution, and exchange.[49] Food production is determined by a variety of factors including land ownership and use; soil management; crop selection, breeding, and management; livestock breeding and management; and harvesting.[17] Crop production can be affected by changes in rainfall and temperatures.[49] The use of land, water, and energy to grow food often compete with other uses, which can affect food production.[50] Land used for agriculture can be used for urbanization or lost to desertification, salinization or soil erosion due to unsustainable agricultural practices.[50] Crop production is not required for a country to achieve food security. Nations do not have to have the natural resources required to produce crops to achieve food security, as seen in the examples of Japan[51][52] and Singapore.[53]

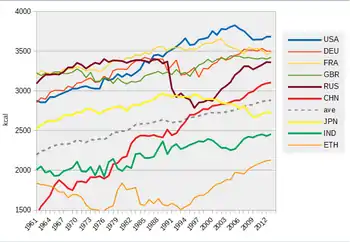

Because food consumers outnumber producers in every country,[53] food must be distributed to different regions or nations. Food distribution involves the storage, processing, transport, packaging, and marketing of food.[17] Food-chain infrastructure and storage technologies on farms can also affect the amount of food wasted in the distribution process.[50] Poor transport infrastructure can increase the price of supplying water and fertilizer as well as the price of moving food to national and global markets.[50] Around the world, few individuals or households are continuously self-reliant on food. This creates the need for a bartering, exchange, or cash economy to acquire food.[49] The exchange of food requires efficient trading systems and market institutions, which can affect food security.[16] Per capita world food supplies are more than adequate to provide food security to all, and thus food accessibility is a greater barrier to achieving food security.[53]

Access

Food access refers to the affordability and allocation of food, as well as the preferences of individuals and households.[49] The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights noted that the causes of hunger and malnutrition are often not a scarcity of food but an inability to access available food, usually due to poverty.[54] Poverty can limit access to food, and can also increase how vulnerable an individual or household is to food price spikes.[16] Access depends on whether the household has enough income to purchase food at prevailing prices or has sufficient land and other resources to grow its food.[55] Households with enough resources can overcome unstable harvests and local food shortages and maintain their access to food.[53]

There are two distinct types of access to food: direct access, in which a household produces food using human and material resources, and economic access, in which a household purchases food produced elsewhere.[17] Location can affect access to food and which type of access a family will rely on.[55] The assets of a household, including income, land, products of labor, inheritances, and gifts can determine a household's access to food.[17] However, the ability to access sufficient food may not lead to the purchase of food over other materials and services.[16] Demographics and education levels of members of the household as well as the gender of the household head determine the preferences of the household, which influences the type of food that is purchased.[55] A household's access to adequate nutritious food may not assure adequate food intake for all household members, as intrahousehold food allocation may not sufficiently meet the requirements of each member of the household.[16] The USDA adds that access to food must be available in socially acceptable ways, without, for example, resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing, or other coping strategies.[1]

Utilization

The next pillar of food security is food utilization, which refers to the metabolism of food by individuals.[53] Once the food is obtained by a household, a variety of factors affect the quantity and quality of food that reaches members of the household. To achieve food security, the food ingested must be safe and must be enough to meet the physiological requirements of each individual.[16] Food safety affects food utilization,[49] and can be affected by the preparation, processing, and cooking of food in the community and household.[17]

Nutritional values[49] of the household determine food choice,[17] and whether food meets cultural preferences is important to utilization in terms of psychological and social well-being.[56] Access to healthcare is another determinant of food utilization since the health of individuals controls how the food is metabolized.[17] For example, intestinal parasites can take nutrients from the body and decrease food utilization.[53] Sanitation can also decrease the occurrence and spread of diseases that can affect food utilization.[17][57] Education about nutrition and food preparation can affect food utilization and improve this pillar of food security.[53]

Stability

Food stability refers to the ability to obtain food over time. Food insecurity can be transitory, seasonal, or chronic.[17] In transitory food insecurity, food may be unavailable during certain periods of time.[16] At the food production level, natural disasters[16] and drought[17] result in crop failure and decreased food availability. Civil conflicts can also decrease access to food.[16] Instability in markets resulting in food-price spikes can cause transitory food insecurity. Other factors that can temporarily cause food insecurity are loss of employment or productivity, which can be caused by illness. Seasonal food insecurity can result from the regular pattern of growing seasons in food production.[17]

Agency

Agency refers to the capacity of individuals or groups to make their own decisions about what foods they eat, what foods they produce, how that food is produced, processed, and distributed within food systems, and their ability to engage in processes that shape food system policies and governance.[7]

Sustainability

Sustainability refers to the long-term ability of food systems to provide food security and nutrition in a way that does not compromise the economic, social, and environmental bases that generate food security and nutrition for future generations.[7]

Effects of food insecurity

Famine and hunger are both rooted in food insecurity. Chronic food insecurity translates into a high degree of vulnerability to famine and hunger; ensuring food security presupposes the elimination of that vulnerability.[58]

Food insecurity can force individuals to undertake risky economic activities such as prostitution.[59]

Food insecurity is also related to obesity for people living in – "food deserts" – neighborhoods where nutritious foods are unavailable or unaffordable. People living in these neighborhoods often have to turn to more accessible but less nutritious food which puts them at greater risk of health issues like obesity, diabetes and heart disease.[60][61][62]

Stunting and chronic nutritional deficiencies

Many countries experience ongoing food shortages and distribution problems. These result in chronic and often widespread hunger amongst significant numbers of people. Human populations can respond to chronic hunger and malnutrition by decreasing body size, known in medical terms as stunting or stunted growth.[63] This process starts in utero if the mother is malnourished and continues through approximately the third year of life. It leads to higher infant and child mortality, but at rates far lower than during famines.[64] Once stunting has occurred, improved nutritional intake after the age of about two years is unable to reverse the damage. Severe malnutrition in early childhood often leads to defects in cognitive development.[65] It, therefore, creates a disparity a between children who did not experience severe malnutrition and those who experience it.[66]

Worldwide, the prevalence of child stunting was 21.3 percent in 2019, or 144 million children. Central Asia, Eastern Asia, and the Caribbean have the largest rates of reduction in the prevalence of stunting and are the only subregions on track to achieve the 2025 and 2030 stunting targets.[67] Between 2000 and 2019, the global prevalence of child stunting declined by one-third.[68]

Data from the 2021 FAO SOFI showed that in 2020, 22.0 percent (149.2 million) of children under 5 years of age were affected by stunting, 6.7 percent (45.4 million) were suffering from wasting and 5.7 percent (38.9 million) were overweight. FAO warned that the figures could be even higher due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.[6]

Africa and Asia account for more than nine out of ten of all children with stunting, more than nine out of ten children with wasting, and more than seven out of ten children who are affected by being overweight worldwide.[6]

Mental health outcomes

Food insecurity is one of the social determinants of mental health. A recent comprehensive systematic review showed that over 50 studies have shown that food insecurity is strongly associated with a higher risk of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders.[69] For depression and anxiety, food-insecure individuals have almost a threefold risk increase compared to food-secure individuals.[70] Research has also found that food insecurity is linked to an increased risk of disordered eating behaviors.[71]

Causes and challenges

Global water crisis

Regionally, Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest number of water-stressed countries of any place on the globe, as of an estimated 800 million people who live in Africa, 300 million live in a water-stressed environment.[72] It is estimated that by 2030, 75 million to 250 million people in Africa will be living in areas of high water stress, which will likely displace anywhere between 24 million and 700 million people as conditions become increasingly unlivable.[72] Because the majority of Africa remains dependent on an agricultural lifestyle and 80 to 90 percent of all families in rural Africa rely upon producing their food,[73] water scarcity translates to a loss of food security.[74]

Land degradation

Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and a decline of agricultural yields.[75] Other causes of land degradation include deforestation, overgrazing, over-exploitation of vegetation for use.[76] Approximately 40 percent of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[77]

Climate change

Climate change will affect agriculture and food production around the world. The reasons include the effects of elevated CO2 in the atmosphere. Higher temperatures and altered precipitation and transpiration regimes are also factors. Increased frequency of extreme events and modified weed, pest, and pathogen pressure are other factors.[79]: 282 Droughts result in crop failures and the loss of pasture for livestock.[80] Loss and poor growth of livestock cause milk yield and meat production to decrease.[81] The rate of soil erosion is 10–20 times higher than the rate of soil accumulation in agricultural areas that use no-till farming. In areas with tilling it is 100 times higher. Climate change worsens this type of land degradation and desertification.[82]: 5

Climate change is projected to negatively affect all four pillars of food security. It will affect how much food is available. It will also affect how easy food is to access through prices, food quality, and how stable the food system is.[83] Climate change is already affecting the productivity of wheat and other staples.[84][85]

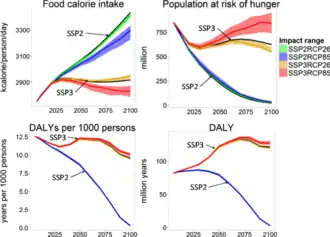

In many areas, fishery catches are already decreasing because of global warming and changes in biochemical cycles. In combination with overfishing, warming waters decrease the amount of fish in the ocean.[86]: 12 Per degree of warming, ocean biomass is expected to decrease by about 5%. Tropical and subtropical oceans are most affected, while there may be more fish in polar waters.[87]Scientific understanding of how climate change would impact global food security has evolved over time. The latest IPCC Sixth Assessment Report in 2022 suggested that by 2050, the number of people at risk of hunger will increase under all scenarios by between 8 and 80 million people, with nearly all of them in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Central America. However, this comparison was done relative to a world where no climate change had occurred, and so it does not rule out the possibility of an overall reduction in hunger risk when compared to present-day conditions.[88]: 717

The earlier Special Report on Climate Change and Land suggested that under a relatively high emission scenario (RCP6.0), cereals may become 1–29% more expensive in 2050 depending on the socioeconomic pathway.[89]: 439 Compared to a scenario where climate change is absent, this would put between 1–181 million people with low income at risk of hunger.[89]Agricultural diseases

Diseases affecting livestock or crops can have devastating effects on food availability especially if there are no contingency plans in place. For example, Ug99, a lineage of wheat stem rust, which can cause up to 100% crop losses, is present in wheat fields in several countries in Africa and the Middle East and is predicted to spread rapidly through these regions and possibly further afield, potentially causing a wheat production disaster that would affect food security worldwide.[90][91]

Food versus fuel

Farmland and other agricultural resources have long been used to produce non-food crops including industrial materials such as cotton, flax, and rubber; drug crops such as tobacco and opium, and biofuels such as firewood, etc. In the 21st century, the production of fuel crops has increased, adding to this diversion. However, technologies are also developed to commercially produce food from energy such as natural gas and electrical energy with tiny water and land footprint.[92][93][94][95]

Food loss and waste

.jpg.webp)

Food waste may be diverted for alternative human consumption when economic variables allow for it. In the 2019 edition of the State of Food and Agriculture, FAO asserted that food loss and waste have potential effects on the four pillars of food security. However, the links between food loss and waste reduction and food security are complex, and positive outcomes are not always certain. Reaching acceptable levels of food security and nutrition inevitably implies certain levels of food loss and waste. Maintaining buffers to ensure food stability requires a certain amount of food to be lost or wasted. At the same time, ensuring food safety involves discarding unsafe food, which then is counted as lost or wasted, while higher-quality diets tend to include more highly perishable foods.[97]

How the impacts on the different dimensions of food security play out and affect the food security of different population groups depends on where in the food supply chain the reduction in losses or waste takes place as well as on where nutritionally vulnerable and food-insecure people are located geographically.[97]

Overfishing

The overexploitation of fish stocks can pose serious risks to food security. Risks can be posed both directly by overexploitation of food fish and indirectly through overexploitation of the fish that those food fish depend on for survival.[98] In 2022 the United Nations called attention "considerably negative impact" on food security of the fish oil and fishmeal industries in West Africa.[99]

Fossil fuel dependence

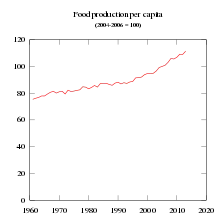

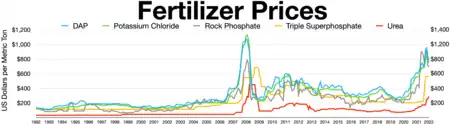

Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by 250%. The energy for the Green Revolution was provided by fossil fuels in the form of fertilizers (natural gas), pesticides (oil), and hydrocarbon-fueled irrigation.[101]

Natural gas is a major feedstock for the production of ammonia, via the Haber process, for use in fertilizer production.[102][103] The development of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer has significantly supported global population growth — it has been estimated that almost half the people on Earth are currently fed as a result of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer use.[104][105]

Disruption in global food supplies due to war

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has disrupted global food supplies[106] which had already been hit hard by the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the growing impact of climate change. The conflict has severely impacted food supply chains with noteworthy effects on production, sourcing, manufacturing, processing, logistics, and significant shifts in demand between nations reliant on imports from Ukraine.[106] In Asia and the Pacific, many of the region's countries depend on the importation of basic food staples such as wheat and fertilizer with nearly 1.1 billion lacking a healthy diet caused by poverty and ever-increasing food prices.[107]

Food prices

During 2022 and 2023 there were food crises in several regions as indicated by rising food prices. In 2022, the world experienced significant food price inflation along with major food shortages in several regions. Sub-Saharan Africa, Iran, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Iraq were most affected.[108][109][110] Prices of wheat, maize, oil seeds, bread, pasta, flour, cooking oil, sugar, egg, chickpea and meat increased.[111][112][113] The causes were disruption in supply chains from the COVID–19 pandemic, an energy crisis (2021–2023 global energy crisis), the Russian invasion of Ukraine and some effects of climate change on agriculture. Significant floods and heatwaves in 2021 destroyed key crops in the Americas and Europe.[114] Spain and Portugal experienced droughts in early 2022 losing 60-80% of the crops in some areas.[115]

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, food prices were already record high. 82 million East Africans and 42 million West Africans faced acute food insecurity in 2021.[116] By the end of 2022, more than 8 million Somalis were in need of food assistance.[117] The Food and Agriculture Organization had reported 20% yearly food price increases in February 2022.[118] The war further pushed this increase to 40% in March 2022 but was reduced to 18% by January 2023.[112] Nevertheless, FAO warns of double-digit food inflation persisting in many countries.[119]Pandemics and disease outbreaks

The World Food Programme has stated that pandemics such as the COVID-19 pandemic risk undermining the efforts of humanitarian and food security organizations to maintain food security.[120] The International Food Policy Research Institute expressed concerns that the increased connections between markets and the complexity of food and economic systems could cause disruptions to food systems during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically affecting the poor.[121] The Ebola outbreak in 2014 led to increases in the prices of staple foods in West Africa.[122]

Possible solutions

Food and Agriculture Organization

Over the last decade, FAO has proposed a "twin track" approach to fight food insecurity that combines sustainable development and short-term hunger relief. Development approaches include investing in rural markets and rural infrastructure.[2] In general, FAO proposes the use of public policies and programs that promote long-term economic growth that will benefit the poor. To obtain short-term food security, vouchers for seeds, fertilizer, or access to services could promote agricultural production. The use of conditional or unconditional food or cash transfers is another approach promoted by FAO. Conditional transfers may include school feeding programs, while unconditional transfers could include general food distribution, emergency food aid or cash transfers. A third approach is the use of subsidies as safety nets to increase the purchasing power of households. FAO has stated that "approaches should be human rights-based, target the poor, promote gender equality, enhance long-term resilience and allow sustainable graduation out of poverty."[123]

FAO has noted that some countries have been successful in fighting food insecurity and decreasing the number of people suffering from undernourishment. Bangladesh is an example of a country that has met the Millennium Development Goal hunger target. The FAO credited growth in agricultural productivity and macroeconomic stability for the rapid economic growth in the 1990s that resulted in an increase in food security. Irrigation systems were established through infrastructure development programs.[4]

In 2020, FAO deployed intense advocacy to make healthy diets affordable as a way to reduce global food insecurity and save vast sums in the process. The agency said that if healthy diets were to become the norm, almost all of the health costs that can currently be blamed on unhealthy diets (estimated to reach US$1.3 trillion a year in 2030) could be offset; and that on the social costs of greenhouse gas emissions that are linked to unhealthy diets, the savings would be even greater (US$1.7 trillion, or over 70 percent of the total estimated for 2030).[124]

FAO urged governments to make nutrition a central plank of their agricultural policies, investment policies and social protection systems. It also called for measures to tackle food loss and waste, and to lower costs at every stage of food production, storage, transport, distribution and marketing. Another FAO priority is for governments to secure better access to markets for small-scale producers of nutritious foods.[124]

The World Summit on Food Security, held in Rome in 1996, aimed to renew a global commitment to the fight against hunger. The conference produced two key documents, the Rome Declaration on World Food Security and the World Food Summit Plan of Action.[9][125] The Rome Declaration called for the members of the United Nations to work to halve the number of chronically undernourished people on the Earth by 2015. The Plan of Action set several targets for government and non-governmental organizations for achieving food security, at the individual, household, national, regional, and global levels.[126]

Another World Summit on Food Security took place at the FAO's headquarters in Rome between November 16 and 18, 2009.[127]

FAO has also created a partnership that will act through the African Union's CAADP framework aiming to end hunger in Africa by 2025. It includes different interventions including support for improved food production, a strengthening of social protection and integration of the Right to Food into national legislation.[128]

World Food Programme

The World Food Programme (WFP) is an agency of the United Nations that uses food aid to promote food security and eradicate hunger and poverty. In particular, the WFP provides food aid to refugees and to others experiencing food emergencies. It also seeks to improve nutrition and quality of life to the most vulnerable populations and promote self-reliance.[129] An example of a WFP program is the "Food For Assets" program in which participants work on new infrastructure, or learn new skills, that will increase food security, in exchange for food.[130]

Global partnerships to achieve food security and end hunger

In April 2012, the Food Assistance Convention was signed, the world's first legally binding international agreement on food aid. The May 2012 Copenhagen Consensus recommended that efforts to combat hunger and malnutrition should be the first priority for politicians and private sector philanthropists looking to maximize the effectiveness of aid spending. They put this ahead of other priorities, like the fight against malaria and AIDS.[131]

By the United States Agency for International Development

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) proposes several key steps to increasing agricultural productivity, which is in turn key to increasing rural income and reducing food insecurity.[132] They include:

- Boosting agricultural science and technology. Current agricultural yields are insufficient to feed the growing populations. Eventually, the rising agricultural productivity drives economic growth.

- Securing property rights and access to finance

- Enhancing human capital through education and improved health

- Conflict prevention and resolution mechanisms and democracy and governance based on principles of accountability and transparency in public institutions and the rule of law are basic to reducing vulnerable members of society.

In September 2022, the United States announced a $2.9 billion contribution to aid efforts of global food security at the UN General Assembly in New York. $2 billion will go to the U.S. Agency for International Development for its humanitarian assistance efforts around the world, along with $140 million for the agency's Feed the Future Initiative. The United States Department of Agriculture will receive $220 million to fund eight new projects, all of which is expected to benefit nearly a million children residing in food-insecure countries in Africa and East Asia. The USDA will also receive another $178 million for seven international development projects to support U.S. government priorities on four continents.[133][134]

Agrifood systems resilience

According to FAO, resilient agrifood systems achieve food security. The resilience of agrifood systems refers to the capacity over time of agrifood systems, in the face of any disruption, to sustainably ensure availability of and access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food for all, and sustain the livelihoods of agrifood systems' actors. Truly resilient agrifood systems must have a robust capacity to prevent, anticipate, absorb, adapt and transform in the face of any disruption, with the functional goal of ensuring food security and nutrition for all and decent livelihoods and incomes for agrifood systems' actors. Such resilience addresses all dimensions of food security, but focuses specifically on stability of access and sustainability, which ensure food security in both the short and the long term.[35] Resilience-building involves preparing for disruptions, particularly those that cannot be anticipated, in particular through: diversity in domestic production, in imports,[135][35] and in supply chains; robust food transport networks;[136][35] and guaranteed continued access to food for all.[137][35]

The FAO finds that there are six pathways to follow towards food systems transformation:[138]

- integrating humanitarian, development and peacebuilding policies in conflict-affected areas;

- scaling up climate resilience across food systems;

- strengthening resilience of the most vulnerable to economic adversity;

- intervening along the food supply chains to lower the cost of nutritious foods;

- tackling poverty and structural inequalities, ensuring interventions are pro-poor and inclusive; and

- strengthening food environments and changing consumer behaviour to promote dietary patterns with positive impacts on human health and the environment.

Improving agricultural productivity to benefit the rural poor

According to the Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture, a major study led by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), managing rainwater and soil moisture more effectively, and using supplemental and small-scale irrigation, hold the key to helping the greatest number of poor people. It has called for a new era of water investments and policies for upgrading rainfed agriculture that would go beyond controlling field-level soil and water to bring new freshwater sources through better local management of rainfall and runoff.[139] Increased agricultural productivity enables farmers to grow more food, which translates into better diets and, under market conditions that offer a level playing field, into higher farm incomes.[140]

Biotechnology and genetically modified (GM) crops

The use of genetically modified (GM) crops could make some contributions to food security in certain cases. The genome of these crops can be altered to address one or more aspects of the plant that may be preventing it from being grown in various regions under certain conditions. Many of these alterations can address the challenges that were previously mentioned above, including the water crisis, land degradation, and the climate change.[141]

In agriculture and animal husbandry, the Green Revolution popularized the use of conventional hybridization to increase yield by creating high-yielding varieties. Often, the handful of hybridized breeds originated in developed countries and was further hybridized with local varieties in the rest of the developing world to create high-yield strains resistant to local climate and diseases.

Some scientists question the safety of biotechnology as a panacea; agroecologists Miguel Altieri and Peter Rosset have enumerated ten reasons why biotechnology will not ensure food security, protect the environment, or reduce poverty. Reasons include for example:[142]

- There is no relationship between the prevalence of hunger in a given country and its population

- Most innovations in agricultural biotechnology have been profit-driven rather than need-driven

- Ecological theory predicts that the large-scale landscape homogenization with transgenic crops will exacerbate the ecological problems already associated with monoculture agriculture

- And, that much of the needed food can be produced by small farmers located throughout the world using existing agroecological technologies.

Alternative diets

Food security could be increased by integrating alternative foods that can be grown in compact environments, that are resilient to pests and disease, and that do not require complex supply chains. Foods meeting these criteria include algae, mealworm, and fungi-derived mycoprotein. While unpalatable on their own to most people, such raw ingredients might be processed into more palatable foods.[143]

Food Justice Movement

The Food Justice Movement has been seen as a unique and multifaceted movement with relevance to the issue of food security. It has been described as a movement about social-economic and political problems in connection to environmental justice, improved nutrition and health, and activism. Today, a growing number of individuals and minority groups are embracing the Food Justice due to the perceived increase in hunger within nations such as the United States as well as the amplified effect of food insecurity on many minority communities, particularly the Black and Latino communities.[144]

A possible way to learn about nutrition, and provide community activities and access to food is community gardening.[145][146]

By country

Food security in particular countries:

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, about 35.5% of households are food insecure (as of 2018). The prevalence of underweight, stunting, and wasting in children under five years of age is also very high.[147] In October 2021, more than half of Afghanistan's 39 million people faced an acute food shortage.[148] On 11 November 2021, Human Rights Watch reported that Afghanistan is facing widespread famine due to collapsed economy and broken banking system. The UN World Food Program has also issued multiple warnings of worsening food insecurity.[149]

Australia

In 2012, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) conducted a survey measuring nutrition, which included food security. It was reported that 4% of Australian households were food insecure.[150] 1.5% of those households were severely food insecure.[150] Additionally, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), reported that certain demographics are more vulnerable to being food insecure; such as indigenous, elderly, regional, and single-parent households.[151] Financial issues were cited as the main cause of food insecurity.[150]

Climate change may present future challenges for Australia regarding food security, as Australia already experiences extreme weather. Australia's history in biofuel production and use of fertilizers has reduced the quality of the land.[152] Increased extreme weather is projected to affect crops, livestock, and soil quality.[153] Wheat production, one of Australia's main food exports, is projected to decrease by 9.2% by 2030.[154] Beef production is also expected to fall by 9.6%.[154]

China

The persistence of wet markets has been described as "critical for ensuring urban food security",[155][156] particularly in Chinese cities.[157] The influence of wet markets on urban food security includes food pricing and physical accessibility.[157]

Calling food waste "shameful", General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping launched "Operation empty plate". Xi stressed that there should be a sense of crisis regarding food security. In 2020, China witnessed a rise in food prices, due to the COVID-19 outbreak and mass flooding that wiped out the country's crops, which made food security a priority for Xi.[158][159]

Democratic Republic of Congo

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, about 33% of households are food insecure; it is 60% in eastern provinces.[160] A study showed the correlation of food insecurity negatively affecting at-risk HIV adults in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[160] Hunger is frequent in the country, but sometimes it is to the extreme that many families cannot afford to eat every day.[161] Bushmeat trade was used to measure the trend of food security. Urban areas mainly consume bushmeat because they cannot afford other types of meat.[162]

Mexico

Singapore

In 2019 the Singapore government launched the "30 by 30" program which aims to drastically reduce food insecurity through hydroponic farms and aquaculture farms.[164][165]

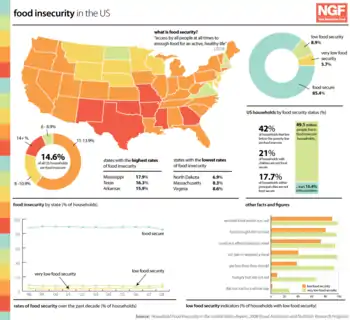

United States

National Food Security Surveys are the main survey tool used by the USDA to measure food security in the United States. Based on respondents' answers to survey questions, the household can be placed on a continuum of food security defined by the USDA. This continuum has four categories: high food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security.[166] The continuum of food security ranges from households that consistently have access to nutritious food to households where at least one or more members routinely go without food due to economic reasons.[167] Economic Research Service report number 155 (ERS-155) estimates that 14.5 percent (17.6 million) of US households were food insecure at some point in 2012.[168]

Data from 2018 about food security in the U.S. shows:[169][170]

- 11.1 percent (14.3 million) of U.S. households were food insecure at some time during 2018.

- In 6.8 percent of households with children, only adults were food insecure in 2018.

- Both children and adults were food insecure in 7.1 percent of households with children (2.7 million households) in 2018.

Food insecurity is measured in the United States by questions in the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey. The questions asked are about anxiety that the household budget is inadequate to buy enough food, inadequacy in the quantity or quality of food eaten by adults and children in the household, and instances of reduced food intake or consequences of reduced food intake for adults and children.[171] A National Academy of Sciences study commissioned by the USDA criticized this measurement and the relationship of "food security" to hunger, adding "it is not clear whether hunger is appropriately identified as the end of the food security scale."[172]

Food insecurity is recognized as a social determinant of health, or a condition in the environment where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.[173]

Poverty is closely associated with food insecurity but this relationship is not foolproof, in that not all people living below the poverty line experience food insecurity, and people who live above the poverty line can also experience food insecurity.[174] Underlying factors of food insecurity relates to economic factors such as income.[175]

Uganda

In 2022, 28% of Ugandan households experienced food insecurity. This insecurity has negative effects on HIV transmission and household stability.[59]

Society and culture

Food security related UN days

October 16 has been chosen as World Food Day, in honour of the date FAO was founded in 1945. On this day, FAO hosts a variety of events at its headquarters in Rome and around the world, as well as seminars with UN officials.[176]

Human rights approach

The United Nations (UN) recognized the Right to Food in the Declaration of Human Rights in 1948,[2] and has since said that it is vital for the enjoyment of all other rights.[177]

United Nations Goals

The UN Millennium Development Goals were one of the initiatives aimed at achieving food security in the world. The first Millennium Development Goal states that the UN "is to eradicate extreme hunger and poverty" by 2015.[140] The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, advocates for a multidimensional approach to food security challenges. This approach emphasizes the physical availability of food; the social, economic and physical access people have to food; and the nutrition, safety and cultural appropriateness or adequacy of food.[178]

Multiple different international agreements and mechanisms have been developed to address food security. The main global policy to reduce hunger and poverty is in the Sustainable Development Goals. In particular Goal 2: Zero Hunger sets globally agreed targets to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture by 2030.[179] Although there has been some progress, the world is not on track to achieve the global nutrition targets, including those on child stunting, wasting and overweight by 2030.[68]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Food Security in the United States: Measuring Household Food Security". USDA. Archived from the original on 22 November 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "Food Security". FAO Agricultural and Development Economics Division. June 2006. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- 1 2 Gary Bickel; Mark Nord; Cristofer Price; William Hamilton; John Cook (2000). "Guide to Measuring Household Food Security" (PDF). USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- 1 2 "The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013. The multiple dimensions of food security" (PDF). FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 FAO (2009). Declaration of the World Food Summit on Food Security (PDF). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021: Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. In brief (2021 ed.). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2021. p. 5. doi:10.4060/cb5409en. ISBN 978-92-5-134634-1.

- 1 2 3 4 "Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030" (PDF). High Level Panel of Experts Report 15: 7–11. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "1996 Summit on World Food Security Report". 1996 Summit on World Food Security Report.

- 1 2 3 Food and Agriculture Organization (November 1996). "Rome Declaration on Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action". Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ "Global Health Is the Best Investment We Can Make". European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ↑ "Global Food Crisis Demands Support for People, Open Trade, Bigger Local Harvests". IMF. 30 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ↑ "Chapter 2. Food security: concepts and measurement". www.fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Food Security". ifpri.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Trade Reforms and Food Security: Conceptualizing the Linkages. FAO, UN. 2003. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ Patel, Raj (20 November 2013). "Raj Patel: 'Food sovereignty' is next big idea". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ecker and Breisinger (2012). The Food Security System (PDF). Washington, D.D.: International Food Policy Research Institute. pp. 1–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 FAO (1997). "The food system and factors affecting household food security and nutrition". Agriculture, food and nutrition for Africa: a resource book for teachers of agriculture. Rome: Agriculture and Consumer Protection Department. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ QAgnes R. Quisumbing, Lynn R. Brown, Hilary Sims Feldstein, Lawrence James Haddad, Christine Peña Women: The key to food security. Archived 2023-01-15 at the Wayback Machine International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Food Policy Report. 26 pages. Washington. 1995

- ↑ Webb, P; Coates, J.; Frongillo, E. A.; Rogers, B. L.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. (2006). "Measuring household food insecurity: why it's so important and yet so difficult to do". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (5): 1404S–1408S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.5.1404S. PMID 16614437. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Perez-Escamilla, Rafael; Segall-Correa, Ana Maria (2008). "Food Insecurity measurement and indicators". Revista de Nutrição. 21 (5): 15–26. doi:10.1590/s1415-52732008000500003.

- ↑ Barrett, C. B. (11 February 2010). "Measuring Food Insecurity". Science. 327 (5967): 825–828. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..825B. doi:10.1126/science.1182768. PMID 20150491. S2CID 11025481.

- 1 2 Swindale, A; Bilinsky, P. (2006). "Development of a universally applicable household food insecurity measurement tool: process, current status, and outstanding issues". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (5): 1449S–1452S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.5.1449s. PMID 16614442. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Cafiero, Carlo; Viviani, S.; Nord, M (2018). "Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale". Measurement. 116: 146–152. Bibcode:2018Meas..116..146C. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2017.10.065. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Swindale, A. & Bilinsky, P. (2006). Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (v.2) (PDF). Washington DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Coates, Jennifer; Anne Swindale; Paula Bilinsky (2007). Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v. 3). Washington, D.C.: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Ballard, Terri; Coates, Jennifer; Swindale, Anne; Deitchler, Megan (2011). Household Hunger Scale: Indicator Definition and Measurement Guide (PDF). Washington DC: FANTA-2 Bridge, FHI 360. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Maxwell, Daniel G. (1996). "Measuring food insecurity: the frequency and severity of "coping strategies"" (PDF). Food Policy. 21 (3): 291–303. doi:10.1016/0306-9192(96)00005-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ↑ Oldewage-Theron, Wilna H.; Dicks, Emsie G.; Napier, Carin E. (2006). "Poverty, household food insecurity and nutrition: Coping strategies in an informal settlement in the Vaal Triangle, South Africa". Public Health. 120 (9): 795–804. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2006.02.009. PMID 16824562.

- ↑ Maxwell, Daniel; Caldwell, Richard; Langworthy, Mark (1 December 2008). "Measuring food insecurity: Can an indicator based on localized coping behaviors be used to compare across contexts?". Food Policy. 33 (6): 533–540. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.02.004.

- ↑ "FAO" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020 – Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets (PDF). Rome: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2020. p. 7. doi:10.4060/ca9692en. ISBN 978-92-5-132901-6. S2CID 239729231. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020, In brief. Rome: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2020. p. 12. doi:10.4060/ca9699en. ISBN 978-92-5-132910-8. S2CID 243701058.

- 1 2 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all (PDF). Rome: FAO. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb4474en. ISBN 978-92-5-134325-8. S2CID 241785130. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- 1 2 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all, In brief. Rome: FAO. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb5409en. ISBN 978-92-5-134634-1. S2CID 243180525.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. Making agrifood systems more resilient to shocks and stresses, In brief. Rome: FAO. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb7351en. ISBN 978-92-5-135208-3. S2CID 244536830.

- 1 2 3 NENA Regional Network on Nutrition-sensitive Food System. Empowering women and ensuring gender equality in agri-food systems to achieve better nutrition − Technical brief. Cairo: FAO. 2023. doi:10.4060/cc3657en. ISBN 978-92-5-137438-2. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Cook, John. "Child Food Insecurity: The Economic Impact on our Nation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Washington Post, November 17, 2009. "America's Economic Pain Brings Hunger Pangs: USDA Report on Access to Food 'Unsettling,' Obama Says"". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ↑ "Individual, Family and Neighborhood Characteristics and Children's Food Insecurity". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2012. JournalistsResource.org. Retrieved April 13, 2012

- ↑ Kimbro, Rachel T.; Denney, Justin T.; Panchang, Sarita (2012). "Individual, Family and Neighborhood Characteristics and Children's Food Insecurity". Journal of Applied Research on Children. 3. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, World Food Programme Gender Policy Report. Rome, 2009.

- ↑ Spieldoch, Alexandra (2011). "The Right to Food, Gender Equality and Economic Policy". Center for Women's Global Leadership (CWGL). Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ The status of women in agrifood systems - Overview. Rome: FAO. 2023. doi:10.4060/cc5060en. S2CID 258145984.

- ↑ Nicholas Tarling (ed.) The Cambridge History of SouthEast Asia Vol.II Part 1 pp139-40

- ↑ Torry, William I. (1986). "Economic Development, Drought, and Famines: Some Limitations of Dependency Explanations". GeoJournal. 12 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1007/BF00213018. ISSN 0343-2521. JSTOR 41143585. S2CID 153358508. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Herzegovina, Bosnia and; Moldova, Republic of; Federation, Russian; Arabia, Saudi; Republic, Syrian Arab (7 November 2003). "Letter dated 7 November 2003 from the Permanent Rerpesentative of Ukraine to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General". Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Hunger is a problem of poverty, not scarcity". 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ WHO. "Food Security". Archived from the original on 6 August 2004. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gregory, P. J.; Ingram, J. S. I.; Brklacich, M. (29 November 2005). "Climate change and food security". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 360 (1463): 2139–2148. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1745. PMC 1569578. PMID 16433099.

- 1 2 3 4 Godfray, H. C. J.; Beddington, J. R.; Crute, I. R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J. F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S. M.; Toulmin, C. (28 January 2010). "Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People". Science. 327 (5967): 812–818. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..812G. doi:10.1126/science.1185383. PMID 20110467. S2CID 6471216.

- ↑ Lama, Pravhat (2017). "Japan's Food Security Problem: Increasing Self-sufficiency in Traditional Food". IndraStra Global (7): 7. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.5220820. S2CID 54636643. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Food self-sufficiency rate fell below 40% in 2010 Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, Japan Times, August 12, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tweeten, Luther (1999). "The Economics of Global Food Security". Review of Agricultural Economics. 21 (2): 473–488. doi:10.2307/1349892. JSTOR 1349892. S2CID 14611170.

- ↑ "The Right to Adequate Food" (PDF). United Nations Human Rights. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 Garrett, J; Ruel, M (1999). Are Determinants of Rural and Urban Food Security and Nutritional Status Different? Some Insights from Mozambique (PDF). Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ Loring, Philip A.; Gerlach, S. Craig (2009). "Food, Culture, and Human Health in Alaska: An Integrative Health Approach to Food Security". Environmental Science and Policy. 12 (4): 466–78. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2008.10.006.

- ↑ Petrikova Ivica, Hudson David (2017). "Which aid initiatives strengthen food security? Lessons from Uttar Pradesh" (PDF). Development in Practice. 27 (2): 220–233. doi:10.1080/09614524.2017.1285271. S2CID 157237160. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ↑ Ayalew, Melaku. "Food Security and Famine and Hunger" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- 1 2 Bayram, Seyma. "Food insecurity is driving women in Africa into sex work, increasing HIV risk Facebook Twitter Flipboard Email". npr.org. NPR. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ Levi, Ronli; Schwartz, Marlene; Campbell, Elizabeth; Martin, Katie; Seligman, Hilary (14 March 2022). "Nutrition standards for the charitable food system: challenges and opportunities". BMC Public Health. 22 (1): 495. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-12906-6. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 8919136. PMID 35287656.

- ↑ Gundersen, Craig; Ziliak, James P. (1 November 2015). "Food Insecurity And Health Outcomes". Health Affairs. 34 (11): 1830–1839. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 26526240. S2CID 704609. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Christian, Thomas (2010). "Grocery Store Access and the Food Insecurity–Obesity Paradox". Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 5 (3): 360–369. doi:10.1080/19320248.2010.504106. S2CID 153607634.

- ↑ Das, Sumonkanti; Hossain, Zakir; Nesa, Mossamet Kamrun (25 April 2009). "Levels and trends in child malnutrition in Bangladesh". Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 24 (2): 51–78. doi:10.18356/6ef1e09a-en. ISSN 1564-4278.

- ↑ Svefors, Pernilla (2018). Stunted growth in children from fetal life to adolescence: Risk factors, consequences and entry points for prevention – Cohort studies in rural Bangladesh. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0305-5. OCLC 1038614749.

- ↑ Robert Fogel (2004). "chpt. 3". The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100: Europe, America, and the Third World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521004886.

- ↑ Bhutta, Zulfiqar A.; Berkley, James A.; Bandsma, Robert H. J.; Kerac, Marko; Trehan, Indi; Briend, André (21 September 2017). "Severe childhood malnutrition". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 3: 17067. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.67. ISSN 2056-676X. PMC 7004825. PMID 28933421.

- ↑ The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020, In brief. Rome: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2020. p. 16. doi:10.4060/ca9699en. ISBN 978-92-5-132910-8. S2CID 243701058.

- 1 2 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020, In brief. Rome: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2020. p. 8. doi:10.4060/ca9699en. ISBN 978-92-5-132910-8. S2CID 243701058.

- ↑ Arenas, D.J., Thomas, A., Wang, J. et al. J GEN INTERN MED (2019) || https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05202-4 Archived 2022-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Fang, Di; Thomsen, Michael R.; Nayga, Rodolfo M. (2021). "The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic". BMC Public Health. 21 (1): 607. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10631-0. PMC 8006138. PMID 33781232.

- ↑ Dolan, Eric W. (30 May 2023). "Heightened food insecurity predicts a range of disordered eating behaviors". PsyPost. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- 1 2 "Conference on Water Scarcity in Africa: Issues and Challenges". Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "Coping With Water Scarcity: Challenge of the 21st Century" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "Better Water Security Translates into Better Food Security". New Security Beat. 8 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ↑ "The Earth Is Shrinking: Advancing Deserts and Rising Seas Squeezing Civilization". Earth-policy.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Chapter 4: Land Degradation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ Ian Sample in science correspondent (30 August 2007). "Global food crisis looms as climate change and population growth strip fertile land". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ Hasegawa, Tomoko; Fujimori, Shinichiro; Takahashi, Kiyoshi; Yokohata, Tokuta; Masui, Toshihiko (29 January 2016). "Economic implications of climate change impacts on human health through undernourishment". Climatic Change. 136 (2): 189–202. Bibcode:2016ClCh..136..189H. doi:10.1007/s10584-016-1606-4.

- ↑ Easterling, W.E., P.K. Aggarwal, P. Batima, K.M. Brander, L. Erda, S.M. Howden, A. Kirilenko, J. Morton, J.-F. Soussana, J. Schmidhuber and F.N. Tubiello, 2007: Chapter 5: Food, fibre and forest products. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 273-313.

- ↑ Ding, Ya; Hayes, Michael J.; Widhalm, Melissa (30 August 2011). "Measuring economic impacts of drought: a review and discussion". Disaster Prevention and Management. 20 (4): 434–446. Bibcode:2011DisPM..20..434D. doi:10.1108/09653561111161752.

- ↑ Ndiritu, S. Wagura; Muricho, Geoffrey (2021). "Impact of climate change adaptation on food security: evidence from semi-arid lands, Kenya" (PDF). Climatic Change. 167 (1–2): 24. Bibcode:2021ClCh..167...24N. doi:10.1007/s10584-021-03180-3. S2CID 233890082.

- ↑ IPCC, 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.- O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. doi:10.1017/9781009157988.001

- ↑ Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. p. 442. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ↑ Vermeulen, Sonja J.; Campbell, Bruce M.; Ingram, John S.I. (21 November 2012). "Climate Change and Food Systems". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 37 (1): 195–222. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-020411-130608. S2CID 28974132.

- ↑ Carter, Colin; Cui, Xiaomeng; Ghanem, Dalia; Mérel, Pierre (5 October 2018). "Identifying the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture". Annual Review of Resource Economics. 10 (1): 361–380. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-022938. S2CID 158817046.

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), ed. (2022), "Summary for Policymakers", The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–36, doi:10.1017/9781009157964.001, ISBN 978-1-009-15796-4, retrieved 24 April 2023

- ↑ Bezner Kerr, Rachel; Hasegawa, Toshihiro; Lasco, Rodel; Bhatt, Indra; et al. "Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and other Ecosystem Products" (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 766.

- ↑ Bezner Kerr, R., T. Hasegawa, R. Lasco, I. Bhatt, D. Deryng, A. Farrell, H. Gurney-Smith, H. Ju, S. Lluch-Cota, F. Meza, G. Nelson, H. Neufeldt, and P. Thornton, 2022: Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and Other Ecosystem Products. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.007.

- 1 2 Mbow C, Rosenzweig C, Barioni LG, Benton TG, Herrero M, Krishnapillai M, et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). In Shukla PR, Skea J, Calvo Buendia E, Masson-Delmotte V, Pörtner HO, Roberts DC, et al. (eds.). Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems.

- ↑ Robin McKie; Xan Rice (22 April 2007). "Millions face famine as crop disease rages". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ "Billions at risk from wheat super-blight". New Scientist (2598): 6–7. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2007.

- ↑ "BioProtein Production" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals – and us". Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "New venture selects Cargill's Tennessee site to produce Calysta FeedKind® Protein". Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "Assessment of environmental impact of FeedKind protein" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ↑ Greenfield, Robin (6 October 2014). "The Food Waste Fiasco: You Have to See it to Believe it!". www.robingreenfield.org.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 In Brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2019 – Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome: FAO. 2023. pp. 15–16. doi:10.4060/cc3657en. ISBN 9789251374382. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Gilbert, Helen (18 April 2019). "Overfishing threatens food security". foodmanufacture.co.uk. Food Manufacture. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ McVeigh, Karen (10 February 2022). "Fish oil and fishmeal industry harming food security in west Africa, warns UN". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ↑ "World population with and without synthetic nitrogen fertilizers". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ↑ Eating Fossil Fuels. EnergyBulletin. Archived June 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mulvaney, Dustin (2011). Green Energy: An A-to-Z Guide. SAGE. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-4129-9677-8. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Soaring fertilizer prices put global food security at risk". Axios. 6 May 2022. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Erisman, Jan Willem; Sutton, MA; Galloway, J; Klimont, Z; Winiwarter, W (October 2008). "How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world". Nature Geoscience. 1 (10): 636–639. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..636E. doi:10.1038/ngeo325. S2CID 94880859. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010.

- ↑ "Fears global energy crisis could lead to famine in vulnerable countries". The Guardian. 20 October 2021. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- 1 2 Jagtap, Sandeep; Trollman, Hana; Trollman, Frank; Garcia-Garcia, Guillermo; Parra-López, Carlos; Duong, Linh; Martindale, Wayne; Munekata, Paulo E. S.; Lorenzo, Jose M.; Hdaifeh, Ammar; Hassoun, Abdo; Salonitis, Konstantinos; Afy-Shararah, Mohamed (14 July 2022). "The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the Global Food Supply Chains". Foods. 11 (14): 2098. doi:10.3390/foods11142098. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 9318935. PMID 35885340.

- ↑ "Easing Food Crisis and Promoting Long-Term Food Security in Asia and the Pacific". Asian Development Bank. 29 September 2022. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ↑ Dehghanpisheh, Babak (27 May 2022). "Economic protests challenge Iran's leaders as hopes for nuclear deal fade". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "'We are going to die': Food shortages worsen Sri Lanka crisis". Al Jazeera. 20 May 2022. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.