| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

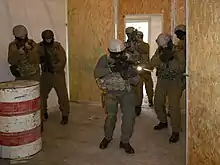

Close-quarters combat (CQC) or close-quarters battle (CQB) is a close combat situation between multiple combatants involving ranged (typically firearm-based) or melee combat.[1] It can occur between military units, law enforcement and criminal elements, and in other similar situations. CQB is typically defined as a short duration, high intensity conflict characterized by sudden violence at close range.

In modern warfare, close-quarters combat usually consists of an engagement between two forces (typically "attackers" and "defenders") of varying size with small arms within a distance of up to 100 meters (110 yards), ranging from close-proximity shootouts to hand-to-hand combat. In the typical CQC scenario, the attackers try a fast takeover of an enclosed area controlled by the defenders, who usually cannot easily withdraw. Because friendly, enemy, and noncombatant personnel can be closely intermingled, CQC demands a rapid assault and precise fire, and units that regularly conduct CQC—such as police tactical units, counterterrorist units, maritime boarding teams, special forces, and commando units—are often specially trained and equipped for CQC tactics.

Although they have some overlap, CQC is not synonymous with urban warfare, as CQC emphasizes infantry tactics using light small arms in a small area of operations, as opposed to the combined arms and much larger areas of urban warfare. Additionally, CQC is not solely limited to enclosed areas, structure interiors, or tight spaces, and can theoretically occur anywhere, such as in and around a structure, aboard a ship, or in a dense rainforest.

History

Close-quarters combat has technically existed in some capacity since the beginning of warfare, in the form of melee combat, the use of ranged weaponry (such as slings, bows, and muskets) at close range, and the necessity of bayonets. During World War I, CQC was a significant part of trench warfare, where enemy soldiers would fight in close and narrow quarters in attempts to capture trenches.

The origins of modern close-quarters combat lie in the combat methods pioneered by Assistant Commissioner William E. Fairbairn of the Shanghai Municipal Police, the police force of the Shanghai International Settlement (1854–1943). After the 1925 May Thirtieth Movement, Fairbairn was tasked with developing a dedicated auxiliary squad for riot control and aggressive policing. After absorbing the most appropriate elements from a variety of martial arts experts, Fairbairn condensed these arts into a martial art he called "defendu". The aim of defendu was to be as brutally effective as possible, while also being relatively easy for recruits and trainees to learn compared to other martial arts. The method incorporated both less-lethal and lethal fighting tactics, such as point shooting, firearm combat techniques, and the use of more ad hoc weapons such as chairs or table legs.

During World War II, Fairbairn was recruited to train Allied special forces in defendu. During this period, he expanded defendu's lethality for military purposes, calling it the "Silent Killing Close Quarters Combat method"; this became standard combat training for British special forces. He also published a textbook for CQC training called Get Tough.[2] U.S. Army officers Rex Applegate and Anthony Biddle were taught Fairbairn's methods at a training facility in Scotland, and adopted the program for the training of Allied operatives at Camp X in Ontario, Canada. Applegate published his work in 1943, called Kill or Get Killed.[3] During the war, training was provided to British Commandos, the First Special Service Force, OSS operatives, U.S. Army Rangers, and Marine Raiders. Other military martial arts were later introduced elsewhere, including European Unifight, Chinese sanshou, Soviet sambo, and the Israeli kapap and Krav Maga.

For a lengthy period following World War II, urban warfare and CQC had barely changed in infantry tactics. Modern firearm CQB tactics were developed in the 1970s as "close-quarters battle" by Western counterterrorist special forces units following the 1972 Munich massacre.[4] The units trained in the aftermath of the massacre, such as the Special Air Service, Delta Force, GSG 9, GIGN, and Joint Task Force 2, developed CQB tactics involving firearms to quickly and precisely assault structures while minimizing friendly and hostage casualties; these CQB tactics were shared between these special forces units, who were closely-knit and frequently trained together.[4] The Special Air Service used CQB tactics during the 1980 Iranian Embassy siege. CQB tactics soon reached police tactical units and similar paramilitaries, such as American SWAT teams, by the 1980s and 1990s.[4]

However, CQB was still not taught to regular infantry, as it was considered a hostage rescue tactic.[4] As late as the 1990s, infantry manuals on urban combat described close-quarters room clearing essentially the same basic way it was described 60 years prior: a grenade being thrown into an enclosed area, followed by an infantry assault with automatic fire.[4] The special forces "monopoly" on CQB was broken following the experiences of urban warfare and close-quarters battles in the 1990s, during the Battle of Mogadishu, the Bosnian War, and the First Chechen War.

The First and Second Battles of Fallujah during the Iraq War were the watershed moments for infantry CQB, when U.S. Marines, under pressure to capture the city of Fallujah, Iraq from insurgents, used conventional combined arms and fire support against the city, and lacked proper CQB training and equipment to effectively clear buildings, causing numerous civilian and allied casualties and severely damaging the city.[4] With similar struggles in towns and cities among ABCA Armies during the War in Afghanistan, a proper approach to infantry in urban warfare became crucial, and CQB tactics began to be taught to infantry.[4]

Some special forces units express disdain at regular infantry being taught CQC, especially in organizational politics and internal matters such as securing budgets; a unit with CQC training requires expensive equipment and training facilities, using up funding that could be used for other units or purposes.[4]

Principles

Planning and preparation

Before conducting a CQC operation, the attackers must gather intelligence on the defenders' capabilities and positioning, as well as the presence and position of any noncombatants or hostages; the defenders may do likewise. Methods of intelligence gathering may include negotiations, surveillance, questioning people who may have intelligence (such as escaped hostages), or consulting maps of the target area.[5]

The attackers organize themselves and diagram and discuss the proposed plan, outlining each team and member's actions and responsibilities, location, fields of fire, and tasks (even to the point of a wall-by-wall and door-by-door layout of the objective, where available). Since the attackers usually already have specialized training, the operation is based on well-understood, pre-established standing operating procedure or rules of engagement. When considerable preparation time is available, the attackers may attempt a siege, negotiate a peaceful resolution, or even conduct training exercises in mockups of the targeted area; however, should there be insufficient time or resources, the attackers must use the knowledge they already have.[5]

Before conducting a CQC operation, a perimeter is often established around the area of operations to prevent the defenders from escaping, stop any assistance they may request from reaching them, keep watch of the defenders from multiple angles, and prevent uninvolved individuals from entering the area and potentially being exposed to crossfire. The size of a perimeter may range from the immediate surroundings to several city blocks. However, in some situations, such as active urban warfare, a perimeter may not be possible or may be unfeasible with the available time and manpower.

Sometimes, negotiations may be attempted between the attackers and defenders before or immediately preceding entry, with the intention of coercing the defenders to surrender, whittling their numbers non-lethally, ensuring the safe release of hostages or noncombatants, or at least drawing the defenders out into a disadvantageous position. Though this tactic is often associated with law enforcement, militaries may also do this when faced with an area containing noncombatants: for example, during the raid on Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's compound, American Delta Force operators surrounded the compound and ordered those inside to come out in Arabic, successfully extracting and securing a number of noncombatants from the compound and separating them from hostiles before making entry.

Surprise

The objective of most CQC operations is to complete all offensive action before the defenders can effectively react. To gain this element of surprise, attackers may use stealth movement and concealment to get as close to the defenders as possible without alerting them, and may launch their assault when least expected or when the defenders' combat readiness is low—for example, while eating or sleeping. Diversions and distractions, such as firecrackers or stun grenades, can draw attention away from the attackers to give them time to get close or make entry without initial resistance. Other forms of distractions include cutting the electricity to the area, making entry while the defenders are communicating with someone (like a negotiator or leader), or even deliberately causing a visible or audible incident such as a structure fire or traffic collision to draw the defenders' attention there.[5]

Entry

The method of entry used depends on numerous factors, including training, equipment, positioning of enemies and noncombatants, and environmental factors.

Regular doors may be breached using anything ranging from kicks and battering rams to explosive breaching charges and blowtorch cutters; larger or more reinforced doors such as garage doors or heavy armored doors may only be opened by the latter, require dedicated tools to breach, or necessitate opening regularly.

In some instances where ground entry is impossible, such as an entryway being barricaded and guarded, or when attacking from multiple points is possible or preferred, different insertion points may be used where possible, such as insertion by helicopter or boat, abseiling to attack through a window or from above, entering from an upper level using an assault ladder, or even digging a tunnel or using existing tunnels or sewers to enter from below. If feasible and authorized, explosives or battering rams may also be used to breach a structure and create another entry point. The entry method used depends on situational circumstances: the presence of hostages or noncombatants may prohibit using explosive breaching charges, while a structure being mostly underground may disqualify using aircraft or abseiling.

Entry is conducted in two forms: deliberate entry, a slow and methodical entry and search done to maximize communication, identification, and the chance of non-violent resolution; and dynamic entry, a rapid and quick entry where enemies are overwhelmed by surprise, but with an increased risk of misidentification and friendly fire, and increasing the likelihood of a lethal response from the defenders.[6] Deliberate entry is often used by law enforcement during raids against suspects unlikely to resist or when securing an area surrounding a target (e.g. to clear an apartment building to focus on a targeted apartment unit), while dynamic entry is often used by both law enforcement and military to quickly defeat enemies before they can act or react or when time is a critical factor (e.g. to stop terrorists from arming a time bomb).

Once the assault begins, the attackers must gain control before the defenders can understand what is happening and prepare an effective defense or mount a counterattack. The defenders sometimes have a contingency plan that could cause the attack to fail, such as killing hostages, detonating bombs, or destroying evidence. If they can execute an organized plan, such as falling back into a prepared stronghold or breaking through the perimeter, the possibility of friendly casualties increases. Speed is achieved through well-designed tactics, such as gaining proximity with an undetected approach, the use of multiple entry points, and explosive breaching. Note that speed does not necessarily translate to actually running, but rather simply quickly and effectively defeating enemies and completing objectives.[7]

Violence of action

Gaining and maintaining physical and psychological momentum is essential for the attackers to secure the scene and maintain control over the situation. The sensory overload caused by the attackers' entry, weaponry, equipment, force, and aggression may overwhelm or surprise the defenders to the extent that they may surrender without fighting back. Enemies may occasionally hide among the hostages, or surrendering enemies may fight back, so the attackers must continue to maintain control over the situation even after the main action.[5]

The defenders often try to stop enemies close to the entry points. The "fatal funnel" is the cone-shaped path leading from an entryway where the attackers are most vulnerable to defenders (e.g. the doorway to a room), essentially being "framed" by the surrounding walls and lacking both effective cover and covering fire. The attackers are also vulnerable from corners closest to the entry point, from which defenders can ambush them upon entry. If the first attackers cannot clear the corners and get out of the fatal funnel, allowing those behind to move in and help, the attack can bog down.[8] A classic CQC tactic, dating back to World War II and still used today, was the deployment of a grenade into a room followed by entry after it detonated, to kill, injure, or otherwise stun enemies throughout the room, including those in corners.[4] CQC tactics to mitigate these threats include having some attackers secure corners in conjunction with a forward assault force; checking the least visible, most prominent, or tactically sound corners first; or simply not entering until all visible hostiles are neutralized, after which corners are checked on entry.

Use

Military

Military uses of close-quarters battle vary by unit type, branch, and mission. Military operations other than war (MOOTW) may involve peacekeeping or riot control. Specialized forces may adapt CQC tactics to their own needs, such as marine naval boarding teams being trained specifically to search ships and fight CQC within them. Hostage rescue or extraction units may involve even more esoteric adaptations or variations, depending on environments, weapons technology, political considerations, or personnel.[9]

Armies that often engage in urban warfare operations may train most of their infantry in basic CQC doctrine as it relates to common tasks such as building entry, clearing a room, and using different types of grenades.[5]

Police and law enforcement

Police tactical units (PTU) are the primary units that engage in CQC domestically. Situations involving the potential for CQC generally involve threats outside of conventional police capabilities, and thus PTUs are trained, equipped, and organized to handle these situations. Additionally, police action is often within what can be considered "close quarters", so members of PTUs are often well-trained in or already experienced with CQC, to the point that some PTUs may train military service members in CQC principles such as breaching and room clearing.

Police CQC doctrine is often specialized by unit type and mission. Depending on the unit or agency's jurisdiction or scope, PTUs may have different goals with different tactics and technology; for example, prison guards may maintain a unit trained in CQC in compact indoors areas such as cells without using lethal force, while a police anti-gang unit may be trained in CQC against multiple enemies that may be difficult to identify.

Unlike their military counterparts, PTUs, as law enforcement officers, are tasked with ideally apprehending suspects alive; for this reason, they are often trained in arrest procedures, non-lethal takedowns, and standoff negotiation instead of solely combat. They may be equipped with less-lethal weaponry such as tasers, pepper spray, and riot guns to fire tear gas, rubber bullets, plastic bullets, or beanbag rounds.

Private industry

Private security and private military companies may maintain units that are trained in CQC. These teams may be responsible for responding to an incident at a facility operated by a government agency that has hired their security services, or to provide protection for VIPs in combat zones. For instance, the U.S. Department of State employed such security teams in Iraq.[10]

Private military and security companies known to maintain units that are trained in, or are capable of training other units in, CQC include Blackwater and SCG International Risk.[11][12]

See also

References

- ↑ "Overview". U.S. Marine Close Combat Fighting Handbook. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. 2011.

- ↑ Chambers, John W., OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II, Washington, D.C., U.S. National Park Service (2008), p. 191.

- ↑ "History of Modern Self-Defence". Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 King, Anthony C. (25 June 2015). "Close Quarters Battle: Urban Combat and 'Special Forcification'". Armed Forces & Society. 42 (2): 276–300. doi:10.1177/0095327x15588292. hdl:10871/17093. ISSN 0095-327X. S2CID 146961496.

- 1 2 3 4 5 U S Department of Defense (2007). U.S. Army Ranger Handbook. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. pp. 200–206. ISBN 978-1-60239-052-2.

- ↑ Southworth, Samuel A.; Tanner, Stephen (2002). U.S. Special Forces: a guide to America's special operations units. Da Capo Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-306-81165-4.

- ↑ Egusa, Alan (2010). Martial Art of the Gun: The Turnipseed Technique. Dog Ear Publishing. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-1-60844-226-3.

- ↑ Kahn, David (2004). Krav maga: an essential guide to the renowned method--for fitness and self-defense. Macmillan. pp. 18–26. ISBN 978-0-312-33177-1.

- ↑ Ford, Roger; Tim Ripley (2001). The whites of their eyes: close-quarter combat. Brassey's. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-57488-379-4.

- ↑ Fitzsimmons, Scott (2016). Private Security Companies during the Iraq War: Military Performance and the Use of Deadly Force. Oxon: Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 9781138844261.

- ↑ Axelrod, Alan (2013). Mercenaries: A Guide to Private Armies and Private Military Companies. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 9781483364667.

- ↑ Engbrecht, Shawn (2011). America's Covert Warriors: Inside the World of Private Military Contractors. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 87. ISBN 9781597972383.

External links

- Lessons Learned: Infantry Squad Tactics in Military Operations in Urban Terrain During Operation Phantom Fury in Fallujah, Iraq - Earl J. Catagnus Jr.; Brad Z. Edison; James D. Keeling; David A. Moon, Marine Corps Gazette; Sep 2005; 89, 9

- "An Infantryman's Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas" FM 90-10-1 12 May 1993