| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

Prehistoric warfare refers to war that occurred between societies without recorded history.

The existence — and the definition — of war in humanity's hypothetical state of nature has been a controversial topic in the history of ideas at least since Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651) argued a "war of all against all", a view directly challenged by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in a Discourse on Inequality (1755) and The Social Contract (1762). The debate over human nature continues, spanning contemporary anthropology, archaeology, ethnography, history, political science, psychology, primatology, and philosophy in such divergent books as Azar Gat's War in Human Civilization and Raymond C. Kelly's Warless Societies and the Origin of War.[1][2] For the purposes of this article, "prehistoric war" will be broadly defined as a state of organized lethal aggression between autonomous preliterate communities.[3][4]

Paleolithic

.jpg.webp)

According to cultural anthropologist and ethnographer Raymond C. Kelly, population density among the earliest hunter-gatherer societies of Homo erectus was probably low enough to avoid armed conflict. The development of the throwing-spear and ambush hunting techniques required cooperation, which made potential violence between hunting parties very costly. The need to prevent competition for resources by maintenance of low population densities may have accelerated the migration out of Africa of H. erectus some 1.8 million years ago as a natural consequence of conflict avoidance.

Hypotheses which suggest that genocidal violence may have caused the extinction of the Neanderthals have been offered by several authors,[5] including Jared Diamond[6] and Ronald Wright.[7] The hypothesis that early humans violently replaced Neanderthals was first proposed by French paleontologist Marcellin Boule (the first person to publish an analysis of a Neanderthal) in 1912.[8] However, several scholars have formed alternative theories as to why the Neanderthals died out, which means there is no clear consensus as to what caused their extinction within the scientific community.[9]

Kelly believes that this period of "Paleolithic warlessness" persisted until well after the appearance of Homo sapiens some 315,000 years ago, ending only at the occurrence of economic and social shifts associated with sedentism, when new conditions incentivized organized raiding of settlements.[10][11]

None of the many cave paintings of the Upper Paleolithic depicts people attacking other people explicitly,[12][13] but there are depictions of human beings pierced with arrows both of the Aurignacian-Périgordian (roughly 30,000 years old) and the early Magdalenian (c. 17,000 years old), possibly representing "spontaneous confrontations over game resources" in which hostile trespassers were killed; however, other interpretations, including capital punishment, human sacrifice, assassination or systemic warfare cannot be ruled out.[14]

While some skeletal and artefactual evidence is suggestive of violent death,[15] clear evidence showing consistent intergroup violence (rather than accidents, homicide etc) is relatively absent.[13] The site of the Jebel Sahaba, estimated to be 13,000 years old, in Sudan contains evidence of a mass grave with wound marks on 24 out of 59 skeletons, although it is an outlier with no other similar sites discovered.[16] Recent research suggests that the Jebel Sahaba did not represent one large site of conflict but collective victims from cumulative interpersonal violence over a period of time, though this does not rule out intergroup conflict as the cause per se as it could still have occurred from multiple skirmishes or raids than a single large battle or massacre.[17]

It has also been suggested that lack of evidence of Paleolithic warfare is due to differences in archaeology resulting in less evidence being likely to survive to be analysed compared to other eras. Since Paleolithic humans lived in small, mobile bands, with low population densities and less durable structures, while also existing further back in history, this results in a lower probability of finding clear evidence as well as that evidence not decaying by the modern day.[18] Furthermore, humans only began to bury their dead 150,000 years ago and not all cultures did so (some preferring to remove them by cremation or exposure), limiting remains that can be found. The absence of fortifications could also be due to the fact that fortifications would be inefficient to construct for society that is primarily nomadic and that only spends a short period of time in one place.[19] Kissel et al. argue that while the general scarcity of evidence from the period suggests warfare may not have been common, it does not support the hypothesis that war was absent.[20]

Epipaleolithic

The most ancient archaeological record of what could have been a prehistoric massacre is at the site of Jebel Sahaba, committed against a population associated with the Qadan culture of far northern Sudan. The cemetery contains a large number of skeletons that are approximately 13,000 to 14,000 years old, almost half of them with arrowheads embedded in their skeletons, which indicates that they may have been the casualties of warfare.[21][22] It has been noted that the violence, if dated correctly, likely occurred in the wake of a local ecological crisis.[23]

At the site of Nataruk in Turkana, Kenya, numerous 10,000-year-old human remains were found with possible evidence of major traumatic injuries, including obsidian bladelets embedded in the skeletons, that should have been lethal.[24] According to the original study, published in January 2016, the region was a "fertile lakeshore landscape sustaining a substantial population of hunter-gatherers" where pottery had been found, suggesting storage of food and sedentism.[25] The initial report concluded that the bodies at Nataruk were not interred, but were preserved in the positions the individuals had died at the edge of a lagoon. However, evidence of blunt-force cranial trauma and lack of interment have been called into question, casting doubt upon the assertion that the site represents early intragroup violence.[26]

The oldest rock art depicting acts of violence between hunter-gatherers in Northern Australia has been tentatively dated to 10,000 years ago.[27]

The earliest, limited evidence for war in Mesolithic Europe likewise dates to ca. 10,000 years ago, and episodes of warfare appear to remain "localized and temporarily restricted" during the Late Mesolithic to Early Neolithic period in Europe.[28] Iberian cave art of the Mesolithic shows explicit scenes of battle between groups of archers.[29] A group of three archers encircled by a group of four is found in Cova del Roure, Morella la Vella, Castellón, Valencia. A depiction of a larger battle (which may, however, date to the early Neolithic), in which eleven archers are attacked by seventeen running archers, is found in Les Dogue, Ares del Maestrat, Castellón, Valencia.[30] At Val del Charco del Agua Amarga, Alcañiz, Aragon, seven archers with plumes on their heads are fleeing a group of eight archers running in pursuit.[31]

Early war was influenced by the development of bows, maces, and slings. The bow seems to have been the most important weapon in early warfare, in that it enabled attacks to be launched with far less risk to the attacker when compared to the risk involved in mêlée combat. While there are no cave paintings of battles between men armed with clubs, the development of the bow is concurrent with the first known depictions of organized warfare consisting of clear illustrations of two or more groups of men attacking each other. These figures are arrayed in lines and columns with a distinctly garbed leader at the front. Some paintings even portray still-recognizable tactics like flankings and envelopments.[32] However, it has also been argued that these paintings should be interpreted with caution due to the fact that it is not self-evident that the cultures that made them intended to depict actual events or if they were intended to be symbolic or otherwise possess a different meaning.[33]

Neolithic

Systemic warfare appears to have been a direct consequence of the sedentism as it developed in the wake of the Neolithic Revolution. An important example is the massacre of Talheim Death Pit (near Heilbronn, Germany), dated right on the cusp of the beginning European Neolithic, at 5500 BC.[34] Investigation of the Neolithic skeletons found in the Talheim Death pit in Germany suggests that prehistoric men from neighboring tribes were prepared to brutally fight and kill each other in order to capture and secure women. Researchers discovered that there were women among the immigrant skeletons, but within the local group of skeletons there were only men and children.[35] They concluded that the absence of women among the local skeletons meant that they were regarded as somehow special, thus they were spared execution and captured instead. The capture of women may have indeed been the primary motive for the fierce conflict between the men.[36][37]

Other speculations about the reasons for violence among Linear Pottery Culture settlements in Neolithic Europe include vengeance, conflicts over land and resources, and kidnapping of slaves. Some of these theories related to the lack of resources are supported by the discovery that various fortifications bordering indigenously inhabited areas appear to have not been in use for very long. Mass burial site at Schletz was also fortified, which serves as evidence of violent conflict among tribes and means that these fortifications were built as a form of defense against aggressors. The massacre of Schletz occurred at the same time as the massacre at Talheim and several other massacres.[38][39][40] More than 200 Neolithic people were killed during the massacre in the Linear Pottery settlement area of Schletz 7000 years ago.[41]

More recently, a similar site was discovered at Schöneck-Kilianstädten, with the remains of the victims showing "a pattern of intentional mutilation".[42] While the presence of such massacre sites in the context of Early Neolithic Europe is undisputed, diverging definitions of "warfare proper" (i.e. planned campaigns sanctioned by society as opposed to spontaneous massacres) has led to scholarly debate on the existence of warfare in the narrow sense prior to the development of city states in 20th-century archaeology. In the summary of Heath (2017), accumulating archaeology has made it "increasingly harder" to argue for the absence of organised warfare in Neolithic Europe.[43]

During the period of expansion of hunter-gatherer groups associated with the Pitted Ware culture in southern Scandinavia, the Funnelbeaker farmers constructed a number of defensive palisades, which may mean that the two peoples were in conflict with each other.[44] There is archaeological evidence of high levels of violence among the people of the Pitted Ware culture.[45][46]

The 8500-year-old Kennewick Man, a prehistoric Paleoamerican man, and Ötzi, who lived and died in the European Alps some 5,200 years ago, were probably killed in warfare.[47]

Warfare in pre-Columbian North America has served as an important comparandum in the archaeological study of the indirect evidence for warfare in the Neolithic. A notable example is the massacre at the Crow Creek Site in South Dakota (14th century).[48][49]

Chalcolithic to Bronze Age

The onset of the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) saw the introduction of copper weapons. Organised warfare between early city states was in existence by the mid-5th millennium BC. Excavations at Mersin, Anatolia show the presence of fortifications and soldiers' quarters by 4300 BC.[50]

Excavation work undertaken in 2005 and 2006 has shown that Hamoukar was destroyed by warfare by around 3500 BC-—probably the earliest urban warfare attested so far in the archaeological record of the Near East.[51] Continued excavations in 2008 and 2010 expand on that.[52]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Proto-Indo-Iranian-speaking Abashevo society was intensely warlike. Mass graves reveal that inter-tribal battles involved hundreds of warriors of both sides. Warfare appears to have been more frequent in the late Abashevo period, and it was in this turbulent environment in which the Sintashta culture emerged.[53] The spread of spoke-wheeled chariots has been closely associated with early Indo-Iranian migrations. The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta culture burial sites, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.[54]

Military conquests expanded city states under Egyptian control. Babylonia and later Assyria built empires in Mesopotamia while the Hittite Empire ruled much of Anatolia. Chariots appear in the 20th century BC, and become central to warfare in the Ancient Near East from the 17th century BC. The Hyksos and Kassite invasions mark the transition to the Late Bronze Age. Ahmose I defeated the Hyksos and re-established Egyptian control of Nubia and Canaan, territories again defended by Ramesses II at the Battle of Kadesh, the greatest chariot battle in history. The raids of the Sea Peoples and the renewed disintegration of Egypt in the Third Intermediate Period marks the end of the Bronze Age.

The Tollense valley battlefield is the oldest evidence of a large scale battle in Europe. More than 4,000 warriors from Central Europe fought in a battle on the site in the 13th century BC.[55]

Mycenaean Greeks (c. 1600 – c. 1100 BC) invested in the development of military infrastructure, while military production and logistics were supervised directly from the palatial centers.[56] The most identifiable piece of Mycenaean armor was the boar's tusk helmet.[57] In general, most features of the later hoplite panoply of classical Greek antiquity, were already known to Mycenaean Greece.[58] The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. It was sudden, violent, and culturally disruptive for many Bronze Age civilizations, and it brought a sharp economic decline to regional powers, notably ushering in the Greek Dark Ages. Historian Robert Drews argues for the appearance of massed infantry, using newly developed weapons and armour, such as cast rather than forged spearheads and long swords, a revolutionizing cut-and-thrust weapon, and javelins. Such new weaponry, in the hands of large numbers of "running skirmishers", who could swarm and cut down a chariot army, would destabilize states that were based upon the use of chariots by the ruling class. That would precipitate an abrupt social collapse as raiders began to conquer, loot and burn cities.[59][60]

The Bronze Age in China traverses the protohistoric and historic periods. Battles utilizing foot and chariot infantry took place regularly between powers in the North China Plain.

Iron Age

Early Iron Age events like the Dorian invasion, Greek colonialism and their interaction with Phoenician and Etruscan forces lie within the prehistoric period. Germanic warrior societies of the Migration period engaged in endemic warfare (see also Thorsberg moor). Anglo-Saxon warfare lies on the edge of historicity, its study relying primarily on archaeology with the help of only fragmentary written accounts.

There are around 3,300 structures that can be classed as hillforts or similar "defended enclosures" within Britain.[61] Hillforts in Britain are known from the Bronze Age, but the great period of hillfort construction was during the British Iron Age, between 700 BC and the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD. The reason for the emergence of hillforts in Britain, and their purpose, has been a subject of debate. It has been argued that they could have been military sites constructed in response to invasion from continental Europe, sites built by invaders, or a military reaction to social tensions caused by an increasing population and consequent pressure on agriculture.[62]

Endemic warfare

In warlike cultures, war is often ritualized with a number of taboos and practices that limit the number of casualties and the duration of the conflict. This type of situation is known as endemic warfare. Among tribal societies engaging in endemic warfare, conflict may escalate to actual warfare occasionally for reasons such as conflict over resources or for no readily understandable reason.

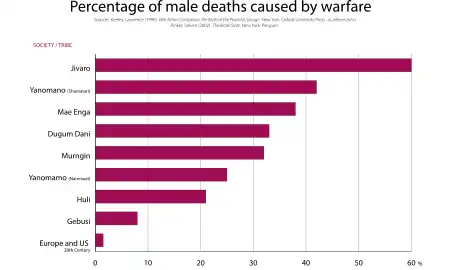

Warfare is known to every tribal society, but some societies developed a particular emphasis of warrior culture (such as the Nuer of South Sudan,[63] the Māori of New Zealand, the Dugum Dani of Papua,[63] the Yanomami (dubbed "the Fierce People") of the Amazon. [63] The culture of inter-tribal warfare has long been present in New Guinea.[64]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gat, Azar (2006). War in Human Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199236633.

- ↑ Kelly, Raymond C. (2000). Warless Societies and the Origin of War. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472067381.

- ↑ Thorpe, I.J.N. (April 2003). "Anthropology, archaeology, and the origin of warfare" (PDF). World Archaeology. 35 (1): 145–165. doi:10.1080/0043824032000079198. S2CID 54030253. JSTOR

- ↑ Lambert, Patricia M. (September 2002). "The Archaeology of war: A North American perspective" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Research. 10 (3): 207–241. doi:10.1023/A:1016063710831. S2CID 141233752. JSTOR

- ↑ Longrich, Nick (1 December 2019). "Were Neanderthals, Denisovans and Other Archaic Humans Victims of Sixth Mass Extinction?". Sci.News. The Conversation.

- ↑ Diamond, J. (1992). The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal. New York: Harper Collins, p. 45.

- ↑ Wright, Ronald (2004). A Short History of Progress. Toronto: House of Anansi Press. pp. 24, 37. ISBN 978-0-88784-706-6.

- ↑ Boule, M 1920, Les hommes fossiles, Masson, Paris.

- ↑ Ashworth, James (31 October 2022). "Neanderthal extinction may have been caused by sex, not fighting". Natural History Museum.

- ↑ Kelly, Raymond C. (2000). Warless Societies and the Origin of War. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472067381.

- ↑ Kelly, Raymond (October 2005). "The evolution of lethal inter-group violence". PNAS. 102 (43): 24–29. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102. PMC 1266108. PMID 16129826. "This period of Paleolithic warlessness, grounded in low population density, an appreciation of the benefits of positive relations with neighbors, and a healthy respect for their defensive capabilities, lasted until the cultural development of segmental forms of organization engendered the origin of war"

- ↑ Guthrie, R. Dale (2005). The Nature of Paleolithic Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-226-31126-5.

- 1 2 Haas, Jonathan and Matthew Piscitelli (2013) "The Prehistory of Warfare: Misled by Ethnography" In War, Peace, and Human Nature edited by Douglas P. Fry, pp. 168-190. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Keith F. Otterbein, How War Began (2004), p. 71f.

- ↑ Keeley, Lawrence H. War before civilization. OUP USA, 1996, pg. 37

- ↑ Horgan, John. "New Study of Prehistoric Skeletons Undermines Claim That War Has Deep Evolutionary Roots". Scientific American.

- ↑ Crevecoeur, Isabelle, Marie-Hélène Dias-Meirinho, Antoine Zazzo, Daniel Antoine, and François Bon. "New insights on interpersonal violence in the Late Pleistocene based on the Nile valley cemetery of Jebel Sahaba." Scientific reports 11, no. 1 (2021): 1-13.

- ↑ Hames, Raymond. "Pacifying hunter-gatherers." Human Nature 30, no. 2 (2019): 155-175, pg. 18

- ↑ Keeley, Lawrence H. War before civilization. OUP USA, 1996, pg. 36-37, 55-56

- ↑ Kissel, Marc, and Nam C. Kim. "The emergence of human warfare: Current perspectives." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 168 (2019): 141-163.

- ↑ Antoine D., Zazzo A., Freidman R., "Revisiting Jebel Sahaba: New Apatite Radiocarbon Dates for One of the Nile Valley's Earliest Cemeteries", American Journal of Physical Anthropology Supplement 56: 68 (2013).

- ↑ Friedman, Renée (14 July 2014). "Violence and climate change in prehistoric Egypt and Sudan". British Museum.

- ↑ Ferguson, R. Brian (July 2000). "The Causes and Origins of "Primitive Warfare": On Evolved Motivations for War". Anthropological Quarterly. George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 73 (3): 159–164. doi:10.1353/anq.2000.0004. JSTOR 3317940. S2CID 49337870. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (20 January 2016). "Stone-age massacre offers earliest evidence of human warfare". The Guardian.

- ↑ Lahr, M. Mirazón; Rivera, F.; Power, R. K.; Mounier, A.; Copsey, B.; Crivellaro, F.; Edung, J. E.; Fernandez, J. M. Maillo; Kiarie, C. (2016). "Inter-group violence among early Holocene hunter-gatherers of West Turkana, Kenya" (PDF). Nature. 529 (7586): 394–398. Bibcode:2016Natur.529..394L. doi:10.1038/nature16477. PMID 26791728. S2CID 4462435. See also: "Evidence of a prehistoric massacre extends the history of warfare". University of Cambridge. 20 Jan 2016. Retrieved 20 Mar 2017., scientificamerican.com

- ↑ Stojanowski, Christopher M.; Seidel, Andrew C.; Fulginiti, Laura C.; Johnson, Kent M.; Buikstra, Jane E. (2016). "Contesting the massacre at Nataruk". Nature. 539 (7630): E8–E10. doi:10.1038/nature19778. PMID 27882979. S2CID 205250945.

- ↑ Taçon, Paul; Chippindale, Christopher (October 1994). "Australia's Ancient Warriors: Changing Depictions of Fighting in the Rock Art of Arnhem Land, N.T.". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 4 (2): 211–248. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001086. S2CID 162983574.

- ↑ Fry (2013), p. 199.

- ↑ Keith F. Otterbein, How War Began (2004), p. 72.

- ↑ Christensen J. 2004. "Warfare in the European Neolithic", Acta Archaeologica 75, 129–156.

- ↑ S.L. Washburn, Social Life of Early Man (1962), p. 207.

- ↑ Keeley, War Before Civilization, 1996, Oxford University Press, pg.45, Fig. 3.1

- ↑ López-Montalvo, Esther. "Violence in Neolithic Iberia: new readings of Levantine rock art." Antiquity 89, no. 344 (2015): 309-327.

- ↑ Lee (2015), p. 18.

- ↑ Highfield, Roger (2008-06-02). "Neolithic men were prepared to fight for their women". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- ↑ "Men Fighting Over Women? It's Nothing New, Suggests Research". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ↑ "Pursuit of Females Dates Way, Way Back". ABC News. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- ↑ Golitko, M. & Keeley, L.H. (2007). "Beating ploughshares back into swords: warfare in the Linearbandkeramik." Antiquity, 81, 332–342.

- ↑ Schulting, Rick (17 August 2015). "Mass grave reveals organised violence among Europe's first farmers". The Conversation.

- ↑ Metcalfe, Tom (3 October 2022). "7,000-year-old mass grave in Slovakia may hold human sacrifice victims". Live Science.

- ↑ Eva Maria Wild et al.: Neolithic Massacres: Local Skirmishes or General Warfare in Europe? In: Radiocarbon. Volume 46, No 1, 2004, S. 377–385, text

- ↑ Christian Meyer et al., "The massacre mass grave of Schöneck-Kilianstädten reveals new insights into collective violence in Early Neolithic Central Europe", PNAS vol. 112 no. 36 (2015), 11217–11222, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504365112.

- ↑ Julian Maxwell Heath, Warfare in Neolithic Europe (2017).

- ↑ Shennan, Stephen (2018). The First Farmers of Europe: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–181. doi:10.1017/9781108386029. ISBN 9781108422925.

- ↑ Ahlström, Torbjörn (April 2012). Sticks, Stones, and Broken Bones: Neolithic Violence in a European Perspective. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199573066.003.0002.

- ↑ Iversen, Rune (December 2016). "Arrowheads as indicators of interpersonal violence and group identity among the Neolithic Pitted Ware hunters of southwestern Scandinavia". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 44: 69–86. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2016.09.004.

- ↑ LeBlanc, Steven (March 2020). The Cambridge World History of Violence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316341247.

- ↑ The Perfect Gift: Prehistoric Massacres. The twin vices of women and cattle in prehistoric Europe Archived 2008-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Zimmerman 1981. The Crow Creek Site Massacre: Preliminary Report.

- ↑ Martin A. Nettleship, Dale Givens, War, its Causes and Correlates, Walter de Gruyter (1975), p. 300.

- ↑ "Archaeologists Unearth a War Zone 5,500 Years Old"

- ↑ http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/nn211.pdf , Clemens D. Reichel, Excavations at Hamoukar Syria, in Oriental Institute Fall 2011 News and Notes, no. 211, pp. 1-9, 2011

- ↑ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. pp. 382–385. ISBN 978-1-4008-3110-4.

- ↑ Kuznetsov, P.F. (2006-09-01). "The emergence of Bronze Age chariots in eastern Europe". Antiquity. 80 (309): 638–645. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00094096. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 162580424.

- ↑ Curry, Andrew (24 March 2016). "Slaughter at the bridge: Uncovering a colossal Bronze Age battle". Science. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ↑ Palaima, Tom (1999). "Mycenaean Militarism from a Textual Perspective" (PDF). Polemos: Warfare in the Aegean Bronze Age (Aegaeum). 19: 367–378. Retrieved 14 October 2015..

- ↑ Schofield, Louise (2006). The Mycenaeans. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-89236-867-9.

- ↑ Kagan, Donald; Viggiano, Gregory F. (2013). Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4008-4630-6.

In fact, most of the essential items of the "hoplite panoply" were known to Mycenaean Greece, including the metallic helmet and the single thrusting spear

- ↑ Drews, R. (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. (Princeton).

- ↑ McGoodwin, Michael. "Drews (Robert) End of Bronze Age Summary". mcgoodwin.net.

- ↑ Hogg, A.H.A. (1979). British Hill-forts: An Index. Oxford: BAR Brit. Ser. 62.

- ↑ Sharples, Niall M (1991), English Heritage Book of Maiden Castle, London: B. T. Batsford, pp. 71–72, ISBN 0-7134-6083-0

- 1 2 3 Diamond, Jared (2012). The world until yesterday : what can we learn from traditional societies?. New York: Viking. pp. 79–129. ISBN 978-0-670-02481-0.

- ↑ "Papua New Guinea massacre of women and children highlights poor policing, gun influx". ABC News. 11 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Fry, Douglas P., War, Peace, and Human Nature. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Karsten, Rafael, Blood revenge, war, and victory feasts among the Jibaro Indians of eastern Ecuador, 1923.

- Kelly, Raymond C. Warless societies and the origin of war. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2000.

- LeBlanc, Steven A. Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest, University of Utah Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0874805819

- Lee, Wayne E., Waging War: Conflict, Culture, and Innovation in World History, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Randsborg, Klavs. Hjortspring : Warfare and Sacrifice in Early Europe. Aarhus, Denmark; Oakville, Connecticut. : Aarhus University Press, 1995.

- Roksandic, Mirjana (ed.), Violent interactions in the Mesolithic : evidence and meaning. Oxford, England : Archaeopress, 2004.