Republic of Mozambique República de Moçambique (Portuguese) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Pátria Amada (Portuguese) "Beloved Homeland" | |

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital and largest city | Maputo 25°57′S 32°35′E / 25.950°S 32.583°E |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Recognised regional languages | Makhuwa, Sena, Tsonga, Lomwe, Changana |

| Ethnic groups (2017)[1] |

|

| Religion (2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Mozambican |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party semi-presidential republic under an authoritarian government[3][4][5] |

| Filipe Nyusi | |

| Adriano Maleiane | |

| Legislature | Assembly of the Republic |

| Formation | |

| 25 June 1975 | |

• Admitted to the United Nations | 16 September 1975 |

| 1977–1992 | |

| 21 December 2004 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 801,590 km2 (309,500 sq mi) (35th) |

• Water (%) | 2.2 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 34,173,805[6] (45th) |

• Density | 28.7/km2 (74.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2014) | high |

| HDI (2021) | low · 185th |

| Currency | Metical (MZN) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Calling code | +258 |

| ISO 3166 code | MZ |

| Internet TLD | .mz |

Website www | |

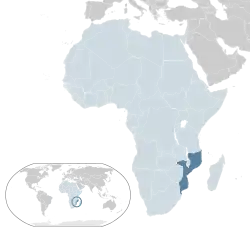

Mozambique (/ˌmoʊzæmˈbiːk/ ⓘ; Portuguese: Moçambique, pronounced [musɐ̃ˈbikɨ]; Chichewa: Mozambiki; Swahili: Msumbiji; Tsonga: Muzambhiki), officially the Republic of Mozambique (República de Moçambique, pronounced [ʁɛˈpuβlikɐ ðɨ musɐ̃ˈbikɨ]), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Africa to the southwest. The sovereign state is separated from the Comoros, Mayotte and Madagascar by the Mozambique Channel to the east. The capital and largest city is Maputo.

Between the 7th and 11th centuries, a series of Swahili port towns developed on that area, which contributed to the development of a distinct Swahili culture and dialect. In the late medieval period, these towns were frequented by traders from Somalia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Arabia, Persia, and India.[10] The voyage of Vasco da Gama in 1498 marked the arrival of the Portuguese, who began a gradual process of colonisation and settlement in 1505. After over four centuries of Portuguese rule, Mozambique gained independence in 1975, becoming the People's Republic of Mozambique shortly thereafter. After only two years of independence, the country descended into an intense and protracted civil war lasting from 1977 to 1992. In 1994, Mozambique held its first multiparty elections and has since remained a relatively stable presidential republic, although it still faces a low-intensity insurgency distinctively in the farthermost regions from the southern capital and where Islam is dominant.

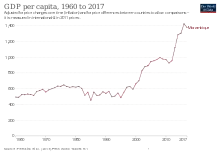

Mozambique is endowed with rich and extensive natural resources, notwithstanding the country's economy is based chiefly on fishery—substantially molluscs, crustaceans and echinoderms—and agriculture with a growing industry of food and beverages, chemical manufacturing, aluminium and oil. The tourism sector is expanding. South Africa remains Mozambique's main trading partner, preserving a close relationship with Portugal[11] with a perspective on other European markets. Since 2001, Mozambique's GDP growth has been thriving, but the nation is still one of the poorest and most underdeveloped countries in the world,[12] ranking low in GDP per capita, human development, measures of inequality and average life expectancy.[13]

The country's population of around 30 million, as of 2022 estimates, is composed of overwhelmingly Bantu peoples. However, the only official language in Mozambique is Portuguese, which is spoken in urban areas as a first or second language by most, and generally as a lingua franca between younger Mozambicans with access to formal education. The most important local languages include Tsonga, Makhuwa, Sena, Chichewa, and Swahili. Glottolog lists 46 languages spoken in the country,[14] of which one is a signed language (Mozambican Sign Language/Língua de sinais de Moçambique). The largest religion in Mozambique is Christianity, with significant minorities following Islam and African traditional religions. Mozambique is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Southern African Development Community, and is an observer at La Francophonie.

Etymology

The country was named Moçambique by the Portuguese after the Island of Mozambique, derived from either Mussa Bin Bique, Musa Al Big, Mossa Al Bique, Mussa Ben Mbiki or Mussa Ibn Malik, an Arab trader who first visited the island and later lived there.[15] The island-town was the capital of the Portuguese colony until 1898, when it was moved south to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo).

History

.jpg.webp)

Bantu migrations

Bantu-speaking peoples migrated into Mozambique as early as the 4th century BC.[16] It is believed between the 1st and 5th centuries AD, waves of migration from the west and north went through the Zambezi River valley and then gradually into the plateau and coastal areas of Southern Africa.[17] They established agricultural communities or societies based on herding cattle. They brought with them the technology for smelting[18] and smithing iron.

Swahili Coast

From the late first millennium AD, vast Indian Ocean trade networks extended as far south into Mozambique as evidenced by the ancient port town of Chibuene.[19] Beginning in the 9th century, a growing involvement in Indian Ocean trade led to the development of numerous port towns along the entire East African coast, including modern day Mozambique. Largely autonomous, these towns broadly participated in the incipient Swahili culture. Islam was often adopted by urban elites, facilitating trade. In Mozambique, Sofala, Angoche, and Mozambique Island were regional powers by the 15th century.[20]

The towns traded with merchants from both the African interior and the broader Indian Ocean world. Particularly important were the gold and ivory caravan routes. Inland states like the Kingdom of Zimbabwe and Kingdom of Mutapa provided the coveted gold and ivory, which were then exchanged up the coast to larger port cities like Kilwa and Mombasa.[21]

Portuguese Mozambique (1498–1975)

The Island of Mozambique after which the country is named, is a small coral island at the mouth of Mossuril Bay on the Nacala coast of northern Mozambique, first explored by Europeans in the late 15th century.

When Portuguese explorers reached Mozambique in 1498, Arab-trading settlements had existed along the coast and outlying islands for several centuries.[22][23] From about 1500, Portuguese trading posts and forts displaced the Arabic commercial and military hegemony, becoming regular ports of call on the new European sea route to the east,[17][24] the first steps in what was to become a process of colonisation.[24][25]

The voyage of Vasco da Gama around the Cape of Good Hope in 1498 marked the Portuguese entry into trade, politics, and society of the region. The Portuguese gained control of the Island of Mozambique and the port city of Sofala in the early 16th century, and by the 1530s, small groups of Portuguese traders and prospectors seeking gold penetrated the interior regions, where they set up garrisons and trading posts at Sena and Tete on the Zambezi and tried to gain exclusive control over the gold trade.[23]

In the central part of the Mozambique territory, the Portuguese attempted to legitimise and consolidate their trade and settlement positions through the creation of prazos.[23] These land grants tied emigrants to their settlements, and inland Mozambique was largely left to be administered by prazeiros, the grant holders, while central authorities in Portugal concentrated their direct exercise of power on, in their view, the more important Portuguese possessions in Asia and the Americas.[23][26] Slavery in Mozambique pre-dated European-contact. African rulers and chiefs dealt in enslaved people, first with Arab Muslim traders, who sent the enslaved to Middle East Asia cities and plantations, and later with Portuguese and other European traders. In a continuation of the trade, slaves were supplied by warring local African rulers, who raided enemy tribes and sold their captives to the prazeiros. The authority of the prazeiros was exercised and upheld amongst the local population by armies of these enslaved men, whose members became known as Chikunda.[23] Continuing emigration from Portugal occurred at comparatively low levels until late in the nineteenth century, promoting "Africanisation".[23] While prazos were originally intended to be held solely by Portuguese colonists, through intermarriage and the relative isolation of prazeiros from ongoing Portuguese influences, the prazos became African-Portuguese or African-Indian.[23][24]

Although Portuguese influence gradually expanded, its power was limited and exercised through individual settlers and officials who were granted extensive autonomy. The Portuguese were able to wrest much of the coastal trade from Arab Muslims between 1500 and 1700, but, with the Arab Muslim seizure of Portugal's key foothold at Fort Jesus on Mombasa Island (now in Kenya) in 1698, the pendulum began to swing in the other direction. As a result, investment lagged while Lisbon devoted itself to the more lucrative trade with India and the Far East and to the colonisation of Brazil.[17]

The Mazrui and Omani Arabs reclaimed much of the Indian Ocean trade, forcing the Portuguese to retreat south. Many prazos had declined by the mid-19th century, but several of them survived. During the 19th century other European powers, particularly the British (British South Africa Company) and the French (Madagascar), became increasingly involved in the trade and politics of the region around the Portuguese East African territories.[27]

By the early 20th century the Portuguese had shifted the administration of much of Mozambique to large private companies, like the Mozambique Company, the Zambezia Company and the Niassa Company, controlled and financed mostly by British financiers such as Solomon Joel, which established railroad lines to their neighbouring colonies (South Africa and Rhodesia). Although slavery had been legally abolished in Mozambique, at the end of the 19th century the chartered companies enacted a forced labour policy and supplied cheap—often forced—African labour to the mines and plantations of the nearby British colonies and South Africa.[17] The Zambezia Company, the most profitable chartered company, took over several smaller prazeiro holdings and established military outposts to protect its property. The chartered companies built roads and ports to bring their goods to market including a railroad linking present-day Zimbabwe with the Mozambican port of Beira.[28][29]

Due to their unsatisfactory performance and the shift, under the corporatist Estado Novo regime of Oliveira Salazar, toward a stronger Portuguese control of Portuguese Empire's economy, the companies' concessions were not renewed when they ran out. This was what happened in 1942 with the Mozambique Company, which, however, continued to operate in the agricultural and commercial sectors as a corporation, and had already happened in 1929 with the termination of the Niassa Company's concession. In 1951, the Portuguese overseas colonies in Africa were rebranded as Overseas Provinces of Portugal.[28][29][30]

The Mueda massacre of 16 June 1960, resulted in the death of Makonde protestors, which provoked the struggle of independence from Portuguese rule of Mozambique.

Mozambican War of Independence (1964–1975)

As communist and anti-colonial ideologies spread out across Africa, many clandestine political movements were established in support of Mozambican independence. These movements claimed that since policies and development plans were primarily designed by the ruling authorities for the benefit of Mozambique's Portuguese population, little attention was paid to Mozambique's tribal integration and the development of its native communities.[31] According to the official guerrilla statements, this affected a majority of the indigenous population who suffered both state-sponsored discrimination and enormous social pressure. As a response to the guerrilla movement, the Portuguese government from the 1960s and principally the early 1970s initiated gradual changes with new socioeconomic developments and egalitarian policies.[32]

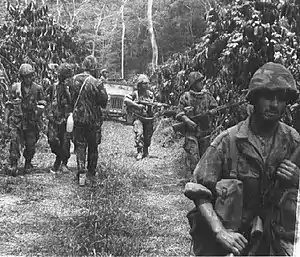

The Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO) initiated a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule in September 1964. This conflict—along with the two others already initiated in the other Portuguese colonies of Angola and Portuguese Guinea—became part of the so-called Portuguese Colonial War (1961–1974). From a military standpoint, the Portuguese regular army maintained control of the population centres while the guerrilla forces sought to undermine their influence in rural and tribal areas in the north and west. As part of their response to FRELIMO, the Portuguese government began to pay more attention to creating favourable conditions for social development and economic growth.[33]

Independence (1975)

FRELIMO took control of the territory after ten years of sporadic warfare, as well as Portugal's own return to democracy after the fall of the authoritarian Estado Novo regime in the Carnation Revolution of April 1974 and the failed coup of 25 November 1975. Within a year, most of the 250,000 Portuguese in Mozambique had left—some expelled by the government of the nearly independent territory, some left the country to avoid possible reprisals from the unstable government—and Mozambique became independent from Portugal on 25 June 1975.[34] A law had been passed on the initiative of the relatively unknown Armando Guebuza of the FRELIMO party, ordering the Portuguese to leave the country in 24 hours with only 20 kilograms (44 pounds) of luggage. Unable to salvage any of their assets, most of them returned to Portugal penniless.[35]

Mozambican Civil War (1977–1992)

.jpg.webp)

The new government under President Samora Machel established a one-party state based on Marxist principles. It received diplomatic and some military support from Cuba and the Soviet Union and proceeded to crack down on opposition.[36] Starting shortly after independence, the country was plagued from 1977 to 1992 by a long and violent civil war between the opposition forces of anti-communist Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO) rebel militias and the FRELIMO regime. This conflict characterised the first decades of Mozambican independence, combined with sabotage from the neighbouring states of Rhodesia and South Africa, ineffective policies, failed central planning, and the resulting economic collapse. This period was also marked by the exodus of Portuguese nationals and Mozambicans of Portuguese heritage,[37] a collapsed infrastructure, lack of investment in productive assets, and government nationalisation of privately owned industries, as well as widespread famine.

During most of the civil war, the FRELIMO-formed central government was unable to exercise effective control outside urban areas, many of which were cut off from the capital.[17] RENAMO-controlled areas included up to 50% of the rural areas in several provinces, and it is reported that health services of any kind were isolated from assistance for years in those areas. The problem worsened when the government cut back spending on health care.[38] The war was marked by mass human rights violations from both sides of the conflict, with both RENAMO and FRELIMO contributing to the chaos through the use of terror and indiscriminate targeting of civilians.[39][40] The central government executed tens of thousands of people while trying to extend its control throughout the country and sent many people to "re-education camps" where thousands died.[39]

During the war, RENAMO proposed a peace agreement based on the secession of RENAMO-controlled northern and western territories as the independent Republic of Rombesia, but FRELIMO refused, insisting on the undivided sovereignty of the entire country. An estimated one million Mozambicans perished during the civil war, 1.7 million took refuge in neighbouring states, and several million more were internally displaced.[41] The FRELIMO regime also gave shelter and support to South African (African National Congress) and Zimbabwean (Zimbabwe African National Union) rebel movements, while the governments of Rhodesia and later Apartheid South Africa backed RENAMO in the civil war.[17] Between 300,000 and 600,000 people died of famine during the war.[42]

On 19 October 1986, Machel was on his way back from an international meeting in Zambia when his plane crashed in the Lebombo Mountains near Mbuzini in South Africa. President Machel and thirty-three others died, including ministers and officials of the Mozambique government. The United Nations' Soviet delegation issued a minority report contending that their expertise and experience had been undermined by the South Africans. Representatives of the Soviet Union advanced the theory that the plane had been intentionally diverted by a false navigational beacon signal, using a technology provided by military intelligence operatives of the South African government.[43]

Machel's successor Joaquim Chissano implemented sweeping changes in the country, starting reforms such as changing from Marxism to capitalism and began peace talks with RENAMO. The new constitution enacted in 1990 provided for a multi-party political system, market-based economy, and free elections. That same year, Mozambique abolished the people's republic as the country's official name. The civil war ended in October 1992 with the Rome General Peace Accords, first brokered by the Christian Council of Mozambique (Council of Protestant Churches) and then taken over by Community of Sant'Egidio. Peace returned to Mozambique, under the supervision of the peacekeeping force of the United Nations.[44][17]

Democratic era (1993–present)

Mozambique held elections in 1994, which were accepted by most political parties as free and fair although still contested by many nationals and observers alike. FRELIMO won, under Joaquim Chissano, while RENAMO, led by Afonso Dhlakama, ran as the official opposition.[45][46] In 1995, Mozambique joined the Commonwealth of Nations, becoming, at the time, the only member nation that had never been part of the British Empire.[47]

By mid-1995, over 1.7 million refugees who had sought asylum in neighbouring countries had returned to Mozambique, part of the largest repatriation witnessed in sub-Saharan Africa. An additional four million internally displaced persons had returned to their homes.[17] In December 1999, Mozambique held elections for a second time since the civil war, which were again won by FRELIMO. RENAMO accused FRELIMO of fraud and threatened to return to civil war but backed down after taking the matter to the Supreme Court and losing.[48][49]

In early 2000, a cyclone caused widespread flooding, killing hundreds and devastating the already precarious infrastructure.[50] There were widespread suspicions that foreign aid resources had been diverted by powerful leaders of FRELIMO. Carlos Cardoso, a journalist investigating these allegations, was murdered,[51][52] and his death was never satisfactorily explained.[53]

Indicating in 2001 that he would not run for a third term,[54] Chissano criticised leaders who stayed on longer than he had, which was generally seen as a reference to Zambian President Frederick Chiluba and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe.[55] Presidential and National Assembly elections took place on 1–2 December 2004. FRELIMO candidate Armando Guebuza won[56] with 64% of the popular vote, and Dhlakama received 32% of the popular vote. FRELIMO won 160 seats in Parliament, with a coalition of RENAMO and several small parties winning the 90 remaining seats. Guebuza was inaugurated as the President of Mozambique on 2 February 2005[57] and served two five-year terms. His successor, Filipe Nyusi, became the fourth President of Mozambique on 15 January 2015.[58][59]

From 2013 to 2019, a low-intensity insurgency by RENAMO occurred, mainly in the country's central and northern regions. On 5 September 2014, Guebuza and Dhlakama signed the Accord on Cessation of Hostilities, which brought the military hostilities to a halt and allowed both parties to concentrate on the general elections to be held in October 2014. However, after the general elections, a new political crisis emerged. RENAMO did not recognise the validity of the election results and demanded the control of six provinces – Nampula, Niassa, Tete, Zambezia, Sofala, and Manica – where they claimed to have won a majority.[60] About 12,000 refugees fled to Malawi.[61] The UNHCR, Doctors Without Borders, and Human Rights Watch reported that government forces had torched villages and carried out summary executions and sexual abuses.[62]

In October 2019, President Filipe Nyusi was re-elected after a landslide victory in general election. FRELIMO won 184 seats, RENAMO got 60 seats and the MDM party received the remaining 6 seats in the National Assembly. Opposition did not accept the results because of allegations of fraud and irregularities. FRELIMO secured two-thirds majority in parliament which allowed FRELIMO to re-adjust the constitution without needing the agreement of the opposition.[63]

Since 2017, the country has faced an ongoing insurgency by Islamist groups.[64][65][66] In September 2020, ISIL insurgents captured and briefly occupied Vamizi Island in the Indian Ocean.[67][68] In March 2021, dozens of civilians were killed and 35,000 others were displaced after Islamist rebels seized the city of Palma.[69][70] In December 2021, nearly 4,000 Mozambicans fled their villages after an intensification of jihadist attacks in Niassa.[71]

Geography

At 309,475 sq mi (801,537 km2), Mozambique is the world's 35th-largest country. Mozambique is located on the southeast coast of Africa and is bound by Eswatini to the south, South Africa to the southwest, Zimbabwe to the west, Zambia and Malawi to the northwest, Tanzania to the north and the Indian Ocean to the east. Mozambique lies between latitudes 10° and 27°S, and longitudes 30° and 41°E.

The country is divided into two topographical regions by the Zambezi River. To the north of the Zambezi, the narrow coastal strip gives way to inland hills and low plateaus. Rugged highlands are further west; they include the Niassa highlands, Namuli or Shire highlands, Angonia highlands, Tete highlands and the Makonde plateau, covered with miombo woodlands. To the south of the Zambezi, the lowlands are broader with the Mashonaland plateau and Lebombo Mountains located in the deep south.

The country is drained by five principal rivers and several smaller ones with the largest and most important the Zambezi. The country has four notable lakes: Lake Niassa (or Malawi), Lake Chiuta, Cahora Bassa and Lake Shirwa, all in the north. The major cities are Maputo, Beira, Nampula, Tete, Quelimane, Chimoio, Pemba, Inhambane, Xai-Xai and Lichinga.

- Geography of Mozambique

.jpg.webp)

Climate

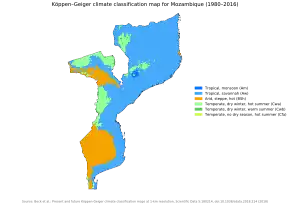

Mozambique has a tropical climate with two seasons: a wet season from October to March and a dry season from April to September. Climatic conditions, however, vary depending on altitude. Rainfall is heavy along the coast and decreases in the north and south. Annual precipitation varies from 500 to 900 mm (19.7 to 35.4 in) depending on the region, with an average of 590 mm (23.2 in). Cyclones are common during the wet season. Average temperature ranges in Maputo are from 13 to 24 °C (55.4 to 75.2 °F) in July and from 22 to 31 °C (71.6 to 87.8 °F) in February.

In 2019 Mozambique suffered floods and destruction from the devastating cyclones Idai and Kenneth, the first time two cyclones had struck the nation in a single season.[72]

Thousands of crops were destroyed during the flooding, which causes transboundary animal diseases, and over 10 million people were affected throughout the region, according to the FAO's urgent campaign for southern Africa, which includes Malawi, Madagascar, and Mozambique. These countries have been experiencing climate disasters between January and March 2023 that have seriously affected various sectors, including farming, fisheries, and thousands of crops.[73]

Wildlife

There are known to be 740 bird species in Mozambique, including 20 globally threatened species and two introduced species, and over 200 mammal species endemic to Mozambique, including the critically endangered Selous' zebra, Vincent's bush squirrel and 13 other endangered or vulnerable species.

Protected areas include thirteen forest reserves, seven national parks, six nature reserves, three frontier conservation areas and three wildlife or game reserves. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.93/10, ranking it 62nd globally out of 172 countries.[74]

Politics

The Constitution of Mozambique stipulates that the President of the Republic functions as the head of state, head of government, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and as a symbol of national unity.[75] He is directly elected for a five-year term via run-off voting; if no candidate receives more than half of the votes cast in the first round of voting, a second round of voting will be held in which only the two candidates who received the highest number of votes in the first round will participate, and whichever of the candidates obtains a majority of votes in the second round will thus be elected president. The prime minister is appointed by the president. His functions include convening and chairing the council of ministers (cabinet), advising the president, assisting the president in governing the country, and coordinating the functions of the other ministers.

The Assembly of the Republic (Assembleia da República) has 250 members, elected for a five-year term by proportional representation. The judiciary comprises a Supreme Court and provincial, district, and municipal courts.

Mozambique operates a small, functioning military that handles all aspects of domestic national defence, the Mozambique Defence Armed Forces.

Foreign relations

While allegiances dating back to the liberation struggle remain relevant, Mozambique's foreign policy has become increasingly pragmatic. The twin pillars of Mozambique's foreign policy are maintenance of good relations with its neighbours[76] and maintenance and expansion of ties to development partners.[17]

During the 1970s and the early 1980s, Mozambique's foreign policy was inextricably linked to the struggles for majority rule in Rhodesia and South Africa as well as superpower competition and the Cold War.[77] Mozambique's decision to enforce UN sanctions against Rhodesia and deny that country access to the sea led Ian Smith's government to undertake overt and covert actions to oppose the country. Although the change of government in Zimbabwe in 1980 removed this threat, the government of South Africa continued to destabilise Mozambique.[17] Mozambique also belonged to the Frontline States.[78] The 1984 Nkomati Accord, while failing in its goal of ending South African support to RENAMO, opened initial diplomatic contacts between the Mozambican and South African governments. This process gained momentum with South Africa's elimination of apartheid, which culminated in the establishment of full diplomatic relations in October 1993. While relations with neighbouring Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania show occasional strains, Mozambique's ties to these countries remain strong.[17]

In the years immediately following its independence, Mozambique benefited from considerable assistance from some Western countries, notably the Scandinavians. The Soviet Union and its allies became Mozambique's primary economic, military and political supporters, and its foreign policy reflected this linkage. This began to change in 1983; in 1984 Mozambique joined the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Western aid by the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland quickly replaced Soviet support.[17] Finland[79] and the Netherlands are becoming increasingly important sources of development assistance. Italy also maintains a profile in Mozambique as a result of its key role during the peace process. Relations with Portugal, the former colonial power, continue to be important because Portuguese investors play a visible role in Mozambique's economy.[17]

Mozambique is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement and ranks among the moderate members of the African bloc in the United Nations and other international organisations. Mozambique also belongs to the African Union and the Southern African Development Community. In 1994, the government became a full member of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, in part to broaden its base of international support but also to please the country's sizeable Muslim population. Similarly, in 1995 Mozambique joined its Anglophone neighbours in the Commonwealth of Nations. At the time it was the only nation to have joined the Commonwealth that was never part of the British Empire. In the same year, Mozambique became a founding member and the first President of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries and maintains close ties with other Portuguese-speaking countries.[17]

Human rights

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 2015.[80] However, discrimination against LGBT people in Mozambique is widespread.[81]

Administrative divisions

Mozambique is divided into ten provinces (provincias) and one capital city (cidade capital) with provincial status. The provinces are subdivided into 129 districts (distritos). The districts are further divided into 405 "postos administrativos" (administrative posts, headed by secretários) and then into localidades (localities), the lowest geographical level of the central state administration. There are 53 "municípios" (municipalities).

|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Maputo  Matola |

1 | Maputo | Maputo | 1,080,277 | 11 | Gurúè | Zambézia | 210,000 | Nampula  Beira |

| 2 | Matola | Maputo | 1,032,197 | 12 | Pemba | Cabo Delgado | 201,846 | ||

| 3 | Nampula | Nampula | 663,212 | 13 | Xai-Xai | Gaza | 132,884 | ||

| 4 | Beira | Sofala | 592,090 | 14 | Maxixe | Inhambane | 123,868 | ||

| 5 | Chimoio | Manica | 363,336 | 15 | Angoche | Nampula | 89,998 | ||

| 6 | Tete | Tete | 307,338 | 16 | Inhambane | Inhambane | 82,119 | ||

| 7 | Quelimane | Zambézia | 246,915 | 17 | Cuamba | Niassa | 79,013 | ||

| 8 | Lichinga | Niassa | 242,204 | 18 | Montepuez | Cabo Delgado | 76,139 | ||

| 9 | Mocuba | Zambézia | 240,000 | 19 | Dondo | Sofala | 70,817 | ||

| 10 | Nacala | Nampula | 225,034 | 20 | Moçambique | Nampula | 65,712 | ||

Economy

Mozambique is one of the poorest and most underdeveloped countries in the world, even though between 1994 and 2006 its average annual GDP growth was approximately 8%. The IMF classifies Mozambique as a heavily indebted poor country. In a 2006 survey, three-quarters of Mozambicans said that in the past five years their economic position had remained the same or become worse.[83] Mozambique was ranked 126th out of 132 in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[84]

Mozambique's official currency is the metical (as of October 2023, US$1 is roughly equivalent to 64 meticals) The U.S. dollar, South African rand, and the euro are widely accepted and used in business transactions. The minimum legal salary is around US$60 per month. Mozambique is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).[17] The SADC free trade protocol is aimed at making the Southern African region more competitive by eliminating tariffs and other trade barriers. The World Bank in 2007 talked of Mozambique's 'blistering pace of economic growth'. A joint donor-government study in early 2007 said 'Mozambique is generally considered an aid success story.'

Rebounding growth

The resettlement of civil war refugees and successful economic reform have led to a high growth rate: the country enjoyed a remarkable recovery, achieving an average annual rate of economic growth of 8% between 1996 and 2006[85] and between 6–7% from 2006 to 2011.[86] Rapid expansion in the future hinges on several major foreign investment projects, continued economic reform, and the revival of the agriculture, transportation, and tourism sectors.[17] In 2013 about 80% of the population was employed in agriculture, the majority of whom were engaged in small-scale subsistence farming[87] which still suffered from inadequate infrastructure, commercial networks, and investment.[17] However, in 2012, more than 90% of Mozambique's arable land was still uncultivated.

In 2013, a BBC article reported that starting in 2009, the Portuguese had been returning to Mozambique because of the growing economy in Mozambique and the poor economic situation in Portugal.[88]

Economic reforms

More than 1,200 mostly small state-owned enterprises have been privatised. Preparations for privatisation and/or sector liberalisation were made for the remaining parastatal enterprises, including telecommunications, energy, ports, and railways. The government frequently selected a strategic foreign investor when privatising a parastatal. Additionally, customs duties have been reduced, and customs management has been streamlined and reformed. The government introduced a value-added tax in 1999 as part of its efforts to increase domestic revenues.

Corruption

Mozambique's economy has been shaken by numerous corruption scandals. In July 2011, the government proposed new anti-corruption laws to criminalise embezzlement, influence peddling and graft, following numerous instances of the theft of public money. This has been endorsed by the country's Council of Ministers. Mozambique convicted two former ministers for graft.[89] Mozambique was ranked 116 of 178 countries in anti-graft watchdog Transparency International's index of global corruption. According to a USAID report written in 2005, "the scale and scope of corruption in Mozambique are cause for alarm."[90]

In 2012, the government of Inhambane province uncovered the misappropriation of public funds by the director of the Provincial Anti-Drugs Office, Calisto Alberto Tomo. He was found to have colluded with the accountant in the Anti-Drugs Office, Recalda Guambe, to steal over 260,000 meticais between 2008 and 2010.[91] The government of Mozambique has taken steps to address the problem of corruption, and some positive developments can be observed, such as the passages of several anti-corruption bills in 2012.[92]

Natural resources

In 2010–2011, Anadarko Petroleum and Eni discovered the Mamba South gas field, recoverable reserves of 4,200 billion cubic metres (150 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas in the Rovuma Basin, off the coast of northern Cabo Delgado Province. Once developed, this could make Mozambique one of the largest producers of liquefied natural gas in the world. In January 2017, 3 firms were selected by the government for the natural gas development projects in the Rovuma gas basin. GL Africa Energy (UK) was awarded one of the tenders. It plans to build and operate a 250 MW gas-powered plant.[93][94] Production was scheduled to start in 2018.[95] Mozambique is now scheduled to begin exporting LNG globally in 2024. In 2019, developments in the Rovuma Basin, referred to as The Mozambique LNG Project, raised $19 billion from a consortium of investors to finally bring this LNG to market. The majority of the project and its associated operations have been awarded to the company, TotalEnergies.[96]

Tourism

The country's natural environment, wildlife, and historic heritage provide opportunities for beach, cultural, and eco-tourism.[97] Mozambique has a great potential for growth in its gross domestic product (GDP).[98]

The north beaches with clean water are suitable for tourism, especially those that are very far from urban centres, such the Quirimbas Islands and the archipelago of Bazaruto.[99] The Inhambane Province attracts international divers because of the marine biodiversity and the presence of whale sharks and manta rays.[100] There are several national parks, including Gorongosa National Park.[101]

Transport

There are over 30,000 km (19,000 mi) of roads, but much of the network is unpaved. Like its Commonwealth neighbours, traffic circulates on the left. There is an international airport at Maputo, 21 other paved airports, and over 100 airstrips with unpaved runways. There are 3,750 km of navigable inland waterways. There are rail links serving principal cities and connecting the country with Malawi, Zimbabwe and South Africa. The Mozambican railway system developed over more than a century from three different ports on the coast that served as terminals for separate lines to the hinterland. The railroads were major targets during the Mozambican Civil War, were sabotaged by RENAMO, and are being rehabilitated. A parastatal authority, Portos e Caminhos de Ferro de Moçambique (Mozambique Ports and Railways), oversees the railway system and its connected ports, but management has been largely outsourced. Each line has its own development corridor.

As of 2005 there were 3,123 km of railway track, consisting of 2,983 km of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge, compatible with neighbouring rail systems, and a 140 km line of 762 mm (2 ft 6 in) gauge, the Gaza Railway.[102] The central Beira–Bulawayo railway and Sena railway route links the port of Beira to the landlocked countries of Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. To the north of this the port of Nacala is also linked by Nacala rail to Malawi, and to the south the port of Maputo is connected by the Limpopo rail, the Goba rail and the Ressano Garcia rail to Zimbabwe, Eswatini and South Africa. These networks interconnect only via neighbouring countries. A new route for coal haulage between Tete and Beira was planned to come into service by 2010,[103] and in August 2010, Mozambique and Botswana signed a memorandum of understanding to develop a 1,100 km railway through Zimbabwe, to carry coal from Serule in Botswana to a deepwater port at Techobanine Point.[104] Newer rolling stock has been supplied by the Indian Golden Rock workshop[105] using Centre Buffer Couplers[106] and air brakes.

Water supply and sanitation

.jpg.webp)

Water supply and sanitation in Mozambique is characterised by low levels of access to an improved water source (estimated to be 51% in 2011), low levels of access to adequate sanitation (estimated to be 25% in 2011) and mostly poor service quality. In 2007 the government defined a strategy for water supply and sanitation in rural areas, where 62% of the population lives. In urban areas, water is supplied by informal small-scale providers and by formal providers.

Beginning in 1998, Mozambique reformed the formal part of the urban water supply sector through the creation of an independent regulatory agency called CRA, an asset-holding company called FIPAG and a public-private partnership (PPP) with a company called Aguas de Moçambique.[107] The PPP covered those areas of the capital and of four other cities that had access to formal water supply systems. However, the PPP ended when the management contracts for four cities expired in 2008 and when the foreign partner of the company that serves the capital under a lease contract withdrew in 2010, claiming heavy losses. While urban water supply has received considerable policy attention, the government has no strategy for urban sanitation yet. External donors finance about 87.4% of all public investments in the sector.

Demographics

| Population[108][109][110] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Thousands | ||

| 1950 | 5,959 | ||

| 1960 | 7,185 | ||

| 1970 | 9,023 | ||

| 1980 | 11,630 | ||

| 1990 | 12,987 | ||

| 2000 | 17,712 | ||

| 2010 | 23,532 | ||

| 2020 | 31,255 | ||

| 2023 | 32,514 | ||

The north-central provinces of Zambezia and Nampula are the most populous, with about 45% of the population. The estimated four million Makua are the dominant group in the northern part of the country; the Sena and Shona (mostly Ndau) are prominent in the Zambezi valley,[17] and the Tsonga and Shangaan people dominate southern Mozambique. Other groups include Makonde, Yao, Swahili, Tonga, Chopi, and Nguni (including Zulu). Bantu people comprise 97.8% of the population, with the rest made up of Portuguese ancestry, Euro-Africans (mestiço people of mixed Bantu and Portuguese ancestry), and Indians.[13] Roughly 45,000 people of Indian descent reside in Mozambique.[111]

During Portuguese colonial rule, a large minority of people of Portuguese descent lived permanently in almost all areas of the country,[112] and Mozambicans with Portuguese heritage at the time of independence numbered about 360,000.[113] Many of these left the country after independence from Portugal in 1975.[114] There are various estimates for the size of Mozambique's Chinese community, ranging from 7,000 to 12,000 as of 2007.[115][116]

According to a 2011 survey, the total fertility rate was 5.9 children per woman, with 6.6 in rural areas and 4.5 in urban areas.[117]

Languages

| Language most spoken at home, 2017 Census[118][119] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emakhuwa | 5,813,083 | 26.13% |

| Portuguese | 3,686,890 | 16.58% |

| Xichangana | 1,919,217 | 8.63% |

| Cinyanja | 1,790,831 | 8.05% |

| Cisena | 1,578,164 | 7.09% |

| Elomwe | 1,574,237 | 7.08% |

| Echuwabo | 1,050,696 | 4.72% |

| Xitswa | 836,644 | 3.76% |

| Cindau | 836,038 | 3.76% |

| Other Mozambican languages | 2,633,088 | 11.84% |

| Other foreign languages | 112,385 | 0.51% |

| None | 4,173 | 0.02% |

| Unknown | 407,927 | 1.83% |

| Total | 22,243,373 | 100.00% |

Portuguese is the official and most widely spoken language of the nation, spoken by 50.3% of the population.[120] The Bantu-group languages that are indigenous to the country vary greatly in their groupings and in some cases are rather poorly appreciated and documented.[121] Apart from its lingua franca uses in the north of the country, Swahili is spoken in a small area of the coast next to the Tanzanian border; south of this, towards Moçambique Island, Kimwani, regarded as a dialect of Swahili, is used. Immediately inland of the Swahili area, Makonde is used, separated farther inland by a small strip of Makhuwa-speaking territory from an area where Yao or ChiYao is used. Makonde and Yao belong to a different group, Yao[122] being very close to the Mwera language of the Rondo Plateau area in Tanzania.[123] Prepositions appear in these languages as locative prefixes prefixed to the noun and declined according to their own noun-class. Some Nyanja is used at the coast of Lake Malawi, as well as on the other side of the Lake.[124][125]

Somewhat different from all of these are the languages of the eMakhuwa group, with a loss of initial k-, which means that many nouns begin with a vowel: for example, epula = "rain".[121] There is eMakhuwa proper, with the related eLomwe and eChuwabo, with a small eKoti-speaking area at the coast. In an area straddling the lower Zambezi, Sena, which belongs to the same group as Nyanja, is spoken, with areas speaking the related CiNyungwe and CiSenga further upriver.

A large Shona-speaking area extends between the Zimbabwe border and the sea: this was formerly known as the Ndau variety[126] but now uses the orthography of the Standard Shona of Zimbabwe. Apparently similar to Shona, but lacking the tone patterns of the Shona language, and regarded by its speakers as quite separate, is CiBalke, also called Rue or Barwe, used in a small area near the Zimbabwe border. South of this area are languages of the Tsonga group. XiTswa or Tswa occurs at the coast and inland, XiTsonga or Tsonga straddles the area around the Limpopo River, including such local dialects as XiHlanganu, XiN'walungu, XiBila, XiHlengwe, and XiDzonga. This language area extends into neighbouring South Africa. Still related to these, but distinct, are GiTonga, BiTonga, and CiCopi or Chopi, spoken north of the mouth of the Limpopo, and XiRonga or Ronga, spoken in the immediate region around Maputo. The languages in this group are, judging by the short vocabularies,[121] very vaguely similar to Zulu, but obviously not in the same immediate group. There are small Swazi- and Zulu-speaking areas in Mozambique immediately next to the Swaziland and KwaZulu-Natal borders.

Arabs, Chinese, and Indians primarily speak Portuguese and some Hindi. Indians from Portuguese India speak any of the Portuguese creoles of their origin aside from Portuguese as their second language.

Religion

The 2007 census found that Christians made up 59.2% of Mozambique's population, Muslims comprised 18.9% of the population, 7.3% of the people held other beliefs, mainly animism, and 13.9% had no religious beliefs.[13][127] A more recent government survey conducted by the Demographic and Health Surveys program in 2015 indicated that Catholicism had increased to 30.5% of the population, Muslims constituted 19.3%, and various Protestant groups a total of 44%.[128] According to 2018 estimates from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 28% of the population is Catholic, 18% are Muslim (mostly Sunni), 15% are Zionist Christians, 12% are Protestants, 7% are members of other religious groups, and 18% have no religion.[129]

The Catholic Church has established twelve dioceses (Beira, Chimoio, Gurué, Inhambane, Lichinga, Maputo, Nacala, Nampula, Pemba, Quelimane, Tete,[130] and Xai-Xai; archdioceses are Beira, Maputo and Nampula). Statistics for the dioceses range from a low 5.8% Catholics in the population in the Diocese of Chimoio, to 32.50% in Quelimane diocese (Anuario catolico de Mocambique). Among the main Protestant denominations are Igreja União Baptista de Moçambique, the Assembleias de Deus, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, the Igreja do Evangelho Completo de Deus, the Igreja Metodista Unida, the Igreja Presbiteriana de Moçambique, the Igrejas de Cristo and the Assembleia Evangélica de Deus. The work of Methodism in Mozambique started in 1890. Erwin Richards began a Methodist mission at Chicuque in Inhambane Province. The Igreja Metodista Unida em Moçambique (United Methodist Church in Mozambique) observed the 100th anniversary of Methodist presence in Mozambique in 1990. President Chissano praised the work and role of the UMC to more than 10,000 people who attended the ceremony. The United Methodist Church has tripled in size in Mozambique since 1998. There are more than 150,000 members in more than 180 congregations of the 24 districts. New pastors are ordained each year. New churches are chartered each year in each Annual Conference (north and south).[131]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has established a growing presence. It first began sending missionaries to Mozambique in 1999, and, as of April 2015, has more than 7,943 members.[132] The Baháʼí Faith has been present in Mozambique since the early 1950s but did not openly identify itself in those years because of the strong influence of the Catholic Church which did not recognise it officially as a world religion. The independence in 1975 saw the entrance of new pioneers. In total, there are about 3,000 declared Baháʼís as of 2010. Muslims are particularly present in the north of the country. They are organised in several "tariqa" or brotherhoods. Two national organisations also exist—the Conselho Islâmico de Moçambique and the Congresso Islâmico de Moçambique. There are also important Pakistani, Indian associations as well as some Shia communities. There is a very small but thriving Jewish community in Maputo.[133]

Health

The fertility rate is at about 5.5 births per woman. Public expenditure on health was at 2.7% of the GDP in 2004, whereas private expenditure on health was at 1.3% in the same year. Health expenditure per capita was 42 US$ (PPP) in 2004. In the early 21st century there were 3 physicians per 100,000 people in the country. Infant mortality was at 100 per 1,000 births in 2005.[134] The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Mozambique is 550. This is compared with 598.8 in 2008 and 385 in 1990. The under 5 mortality rate, per 1,000 births is 147 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5s mortality is 29. In Mozambique the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is 3 and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women 1 in 37.[135]

The official HIV prevalence in 2011 was 11.5% of the population aged between 15 and 49 years. In the southern parts of Mozambique—Maputo and Gaza provinces as well as the city of Maputo—the official figures are more than twice as high as the national average. In 2011 the health authorities estimated about 1.7 million Mozambicans were HIV-positive, of whom 600,000 were in need of anti-retroviral treatment. As of December 2011, 240,000 were receiving such treatment, increasing to 416,000 in March 2014 according to the health authorities.

Education

Portuguese is the primary language of instruction in all Mozambican schools. All Mozambicans are required by law to attend school through the primary level; however, a lot of children do not go to primary school because they have to work for their families' subsistence farms for a living. In 2007, one million children still did not go to school, most of them from poor rural families, and almost half of all teachers were unqualified. Girls enrollment increased from 3 million in 2002 to 4.1 million in 2006 while the completion rate increased from 31,000 to 90,000, which testified a very poor completion rate.[136]

After grade 7, pupils must take standardised national exams to enter secondary school, which runs from eighth to 10th grade.[137] Space in Mozambican universities is extremely limited; thus most pupils who complete pre-university school do not immediately proceed on to university studies. Many go to work as teachers or are unemployed. There are also institutes that give more vocational training, specialising in agricultural, technical or pedagogical studies, which students may attend after grade 10 in lieu of a pre-university school. After independence from Portugal in 1975, a number of Mozambican pupils continued to be admitted every year at Portuguese high schools, polytechnical institutes and universities, through bilateral agreements between the Portuguese government and the Mozambican government.

According to 2010 estimates, the literacy rate was 56.1% (70.8% male and 42.8% female).[138] By 2015, this had increased to 58.8% (73.3% male and 45.4% female).[139]

Pupils in front of their school in Nampula

Pupils in front of their school in Nampula School children in the classroom

School children in the classroom

Culture

.jpg.webp)

Mozambique was ruled by Portugal, and they share a main language (Portuguese) and main religion (Roman Catholicism). But since most of the people of Mozambique are Bantus, most of the culture is native; for Bantus living in urban areas, there is some Portuguese influence. Mozambican culture also influences the Portuguese culture.

Arts

The Makonde are known for their wood carving and elaborate masks, which are commonly used in traditional dances. There are two different kinds of wood carvings: shetani, (evil spirits), which are mostly carved in heavy ebony, tall, and elegantly curved with symbols and nonrepresentational faces; and ujamaa, which are totem-type carvings which illustrate lifelike faces of people and various figures. These sculptures are usually referred to as "family trees" because they tell stories of many generations.

During the last years of the colonial period, Mozambican art reflected the oppression by the colonial power and became a symbol of resistance. After independence in 1975, modern art came into a new phase. The two best known and most influential contemporary Mozambican artists are the painter Malangatana Ngwenya and the sculptor Alberto Chissano. A lot of the post-independence art during the 1980s and 1990s reflect the political struggle, civil war, suffering, starvation, and struggle.

Dances are usually intricate, highly developed traditions throughout Mozambique. There are many different kinds of dances from tribe to tribe which are usually ritualistic in nature. The Chopi, for instance, act out battles dressed in animal skins. The men of Makua dress in colourful outfits and masks while dancing on stilts around the village for hours. Groups of women in the northern part of the country perform a traditional dance called tufo, to celebrate Islamic holidays.[140]

Cuisine

With a nearly 500-year presence in the country, the Portuguese have greatly influenced Mozambique's cuisine. Staples and crops such as cassava (a starchy root of Brazilian origin) and cashew nuts (also of Brazilian origin, though Mozambique was once the largest producer of these nuts), and pãozinho (pronounced [pɐ̃wˈzĩɲu], Portuguese-style buns), were brought in by the Portuguese. The use of spices and seasonings such as bay leaves, chili peppers, fresh coriander, garlic, onions, paprika, red sweet peppers, and wine were introduced by the Portuguese, as were maize, potatoes, rice, and sugarcane. espetada, the popular inteiro com piripiri (whole chicken in piri-piri sauce), prego (steak roll), pudim (pudding), and rissóis (battered shrimp) are all Portuguese dishes commonly eaten in present-day Mozambique.

Media

Mozambican media is heavily influenced by the government.[141] Newspapers have relatively low circulation rates because of high newspaper prices and low literacy rates.[141] Among the most highly circulated newspapers are state-controlled dailies, such as Noticias and Diário de Moçambique, and the weekly Domingo.[142] Their circulation is mostly confined to Maputo.[143] Most funding and advertising revenue is given to pro-government newspapers.[141]

Radio programmes are the most influential form of media in the country because of ease of access.[141] State-owned radio stations are more popular than privately owned media. This is exemplified by the government radio station, Rádio Moçambique, the most popular station in the country.[141] It was established shortly after Mozambique's independence.[144] The television stations watched by Mozambicans are STV, TIM, and TVM Televisão Moçambique. Through cable and satellite, viewers can access tens of other African, Asian, Brazilian, and European channels.

Music

The music of Mozambique serves many purposes, ranging from religious expression to traditional ceremonies. Musical instruments are usually handmade. Some of the instruments used in Mozambican musical expression include drums made of wood and animal skin; the lupembe, a woodwind instrument made from animal horns or wood; and the marimba, which is a kind of xylophone native to Mozambique and other parts of Africa. The marimba is a popular instrument with the Chopi of the south-central coast, who are famous for their musical skill and dance.

National holidays

| Date | National holiday designation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 January | Universal fraternity day | New year |

| 3 February | Mozambican heroes day | In tribute to Eduardo Mondlane |

| 7 April | Mozambican women day | In tribute to Josina Machel |

| 1 May | International workers day | Workers' Day |

| 25 June | National Independence day | Independence proclamation in 1975 (from Portugal) |

| 7 September | Victory Day | In tribute to the Lusaka Accord signed in 1974 |

| 25 September | National Liberation Armed Forces Day | In tribute to the start of the armed fight for national liberation |

| 4 October | Peace and Reconciliation | In tribute to the General Peace Agreement signed in Rome in 1992 |

| 25 December | Family Day | Christians also celebrate Christmas |

Sport

Football (Portuguese: futebol) is the most popular sport in Mozambique. The national team is the Mozambique national football team. Track and field and basketball are also avidly followed in the country.[145] Roller hockey is popular, and the best result for the national team was when they came in fourth at the 2011 FIRS Roller Hockey World Cup. The women's beach volleyball team finished 2nd at the 2018–2020 CAVB Beach Volleyball Continental Cup.[146] The Mozambique national cricket team represents the nation in international cricket.

See also

References

- ↑ "Mozambique", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 23 September 2022, retrieved 4 October 2022

- ↑ "National Profiles". www.thearda.com.

- ↑ Neto, Octávio Amorim; Lobo, Marina Costa (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries". SSRN 1644026.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns". French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. S2CID 73642272.

Of the contemporary cases, only four provide the assembly majority an unrestricted right to vote no confidence, and of these, only two allow the president unrestricted authority to appoint the prime minister. These two, Mozambique and Namibia, as well as the Weimar Republic, thus resemble most closely the structure of authority depicted in the right panel of Figure 3, whereby the dual accountability of the cabinet to both the president and the assembly is maximized.

- ↑ "Mozambique Population (2024) - Worldometer".

- 1 2 3 4 "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Mozambique)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ↑ Newitt, M.D.D. "A Short History of Mozambique." Oxford University Press, 2017

- ↑ African Development Bank and Portugal sign EUR 400 million guarantee agreement to underpin Lusophone Compact, © 2022 African Development Bank, Amba Mpoke-Bigg, Retrieved 06.09.2022

- ↑ Investing in rural people in Mozambique Archived 27 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. ifad.org

- 1 2 3

This article incorporates public domain material from "Mozambique". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). CIA. Retrieved 22 May 2007. (Archived 2007 edition)

This article incorporates public domain material from "Mozambique". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). CIA. Retrieved 22 May 2007. (Archived 2007 edition) - ↑ "Glottolog 4.7 – Languages of Mozambique". glottolog.org. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ History. ilhademo.net

- ↑ Lander, Faye; Russell, Thembi (2018). "The archaeological evidence for the appearance of pastoralism and farming in southern Africa". PLOS ONE. 13 (6): e0198941. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398941L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198941. PMC 6002040. PMID 29902271.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Mozambique (07/02)". U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets/Background Notes. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Mozambique (07/02)". U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets/Background Notes. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018. - ↑ Lyaya, Edwinus Chrisantus. "Metallurgy in Tanzania". ResearchGate. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ↑ Sinclair, Paul; Ekblom, Anneli; Wood, Marilee (2012). "Trade and Society on the Southeast African Coast in the Later First Millennium AD: the Case of Chibuene". Antiquity. 86 (333): 723–737. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047876. S2CID 160887653.

- ↑ Rathee, D. (2021). "Hunt for Oil in Offshore Angoche, Mozambique". Fifth EAGE Eastern Africa Petroleum Geoscience Forum. European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers: 1–5. doi:10.3997/2214-4609.2021605026. S2CID 236669258.

- ↑ Newitt, Malyn. "Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City" 2004.

- ↑ Gupta, Pamila (2019). Portuguese decolonization in the Indian Ocean world: History and ethnography. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781350043657.: 27

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Isaacman, Allen; Peterson, Derek (2006). "Making the Chikunda: Military Slavery and Ethnicity in Southern Africa, 1750–1900". In Brown, Christopher Leslie; Morgan, Philip D. (eds.). Arming Slaves: From Classical Times to the Modern Age. Yale University Press. pp. 95–119. doi:10.12987/yale/9780300109009.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-300-13485-8.

- 1 2 3 Sheldon, Kathleen Eddy; Penvenne, Jeanne Marie. "Mozambique: Arrival of the Portuguese". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ Newitt, Malyn (2004). "Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of an East African Coastal City, 1500–1700". Portuguese Studies. 20: 21–37. doi:10.1353/port.2004.0001. ISSN 0267-5315. JSTOR 41105216. S2CID 245842110. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ Isaacman, Allen (2000). "Chikunda transfrontiersmen and transnational migrations in pre-colonial South Central Africa, ca 1850–1900". Zambezia. 27 (2): 109. hdl:10520/AJA03790622_4.

- ↑ Austin, Gareth (1 March 2010). "African Economic Development and Colonial Legacies". International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement (1): 11–32. doi:10.4000/poldev.78. ISSN 1663-9375. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- 1 2 The Cambridge history of Africa Archived 14 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Cambridge history of Africa, John Donnelly Fage, A. D. Roberts, Roland Anthony Oliver, Edition: Cambridge University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-521-22505-1, ISBN 978-0-521-22505-2

- 1 2 The Third Portuguese Empire, 1825–1975 Archived 23 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Third Portuguese Empire, 1825–1975: A Study in Economic Imperialism, W. G. Clarence-Smith, Edition: Manchester University Press ND, 1985, ISBN 0-7190-1719-X, 9780719017193

- ↑ Agência Geral do Ultramar. dgarq.gov.pt

- ↑ Dinerman, Alice (26 September 2007). Independence redux in postsocialist Mozambique. ipri.pt

- ↑ "piri piri | BOOK OF DAYS TALES". www.bookofdaystales.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ "CD do Diário de Notícias – Parte 08". Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2010 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Keesing's Contemporary Archives, page 27245.

- ↑ Couto, Mia (April 2004). Carnation revolution Archived 2 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Le Monde diplomatique

- ↑ Mozambique: a tortuous road to democracy by J .Cabrita, Macmillan 2001 ISBN 978-0-333-92001-5

- ↑ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire Archived 23 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Time (Monday, 7 July 1975).

- ↑ Pfeiffer, J (2003). "International NGOs and primary health care in Mozambique: The need for a new model of collaboration". Social Science & Medicine. 56 (4): 725–38. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00068-0. PMID 12560007.

- 1 2 Table 14.1C Centi-Kilo Murdering States: Estimates, Sources and Calculations Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. hawaii.edu

- ↑ Gersony 1988, p.30f.

- ↑ Perlez, Jane (13 October 1992). A Mozambique Formally at Peace Is Bled by Hunger and Brutality Archived 26 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ↑ "Mozambique". Mozambique | Communist Crimes. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Special Investigation into the death of President Samora Machel". Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, vol.2, chapter 6a. Archived from the original on 13 April 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ↑ UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN MOZAMBIQUE. popp.gmu.edu

- ↑ Keller, Bill (28 October 1994). "Mozambican Elections Thrown in Doubt (Published 1994)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Frelimo | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Commonwealth | History, Members, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Mozambique: 1999 Election review". www.eisa.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Frelimo's election win to be challenged". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Mozambique: How disaster unfolded". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Hanlon, Joseph (24 November 2000). "Carlos Cardoso". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Mozambique News Agency – AIM Reports". www.poptel.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Attacks on the Press 2001: Mozambique". Committee to Protect Journalists. 26 March 2002. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "No third term for Mozambique president". 9 May 2001. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "afrol News: Mozambican President not going for third term". afrol.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Wines (NYT), Michael (18 December 2004). "World Briefing | Africa: Mozambique: Election Winner Declared (Published 2004)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "New President Pledges Unrelenting Fight Against Poverty". 2005.

- ↑ "Mozambique profile – Timeline". BBC News. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Mozambique swears in new president, opposition stays away". Reuters. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Bueno, Natália. "Provincial Autonomy: The Territorial Dimension of Peace in Mozambique". GIGA Focus.

- ↑ "Mozambican refugees stuck between somewhere and nowhere". Al Jazeera. 22 July 2016. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ "Mozambique's Invisible Civil War". foreign policy. 22 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ "Mozambique: President Filipe Nyusi re-elected in landslide victory". Deutsche Welle. 27 October 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ "'Jihadists behead' Mozambique villagers". BBC News. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ↑ "Religious unrest in Mozambique – in pictures". the Guardian. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ↑ "Mozambique country profile". BBC News. 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ↑ "ISIS take over luxury islands popular among A-list celebrities". News.com.au. 18 September 2020. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ↑ Hanlon, Joseph (29 September 2020). "Mozambique: Police Claim Control Of Empty Mocimboa, From A Distance". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ "Rebels leave beheaded bodies in streets of Mozambique town". AP NEWS. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ "Mozambique: Dozens dead after militant assault on Palma". BBC News. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ "Thousands flee Niassa as jihadist attacks spread to other parts of Mozambique". News24. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ↑ Walsh, Declan (20 April 2019). "Amid a Cyclone's Floods and Destruction, Mozambique Finds Shards of Hope". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ↑ "Subregional Southern Africa – Climate hazards: Urgent call for assistance - Madagascar | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 17 May 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ↑ Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ↑ "Article 119" (PDF). Constitution of the Republic of Mozambique.

- ↑ Schenoni, Luis (2017) "Subsystemic Unipolarities?"in Strategic Analysis, 41(1): 74–86 Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mozambique Archived 4 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine. State.gov (13 June 2012). Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ sahoboss (30 March 2011). "Frontline States". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ↑ President Halonen: Development aid should be transparent and efficient. Office of the President of the Republic of Finland. tpk.fi

- ↑ "Mozambique decriminalises gay and lesbian relationships". BBC News. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ↑ "Mozambique's enduring discrimination leaves gay men untreated for HIV". The Guardian. 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ↑ "Mozambique". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ↑ Hanlon, Joseph (19 September 2007). Is Poverty Decreasing in Mozambique? Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Open University, England.

- ↑ WIPO (4 January 2024). Global Innovation Index 2023, 15th Edition. World Intellectual Property Organization. doi:10.34667/tind.46596. ISBN 978-92-805-3432-0. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ "Mozambique | Þróunarsamvinnustofnun Íslands" (in Icelandic). Iceida.is. 1 June 1999. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ World DataBank World Development Indicators Mozambique The World Bank (2013). Retrieved 5 April 2013

- ↑ Mozambique Archived 27 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Canadian International Development Agency (29 January 2013). Retrieved 6 April 2013

- ↑ Akwagyiram, Alexis (5 April 2013) Portugal's unemployed heading to Mozambique 'paradise' Archived 29 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News Africa. Retrieved 6 April 2013

- ↑ "Mozambique proposes new anti-corruption laws". Agence France-Presse. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014.

- ↑ "CORRUPTION ASSESSMENT: MOZAMBIQU" (PDF). USAID. 16 December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "Mozambique: Corruption Alleged in Anti-Drugs Office". All Africa. 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ↑ "Mozambique Corruption Profile". Business Anti-Corruption Profile. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ "Great Lakes Africa Energy | Our Projects". www.glaenergy.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ↑ kig, Antony; a (2 February 2017). "GLA Energy to construct 250MW gas powered plant in Mozambique". Construction Review Online. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ↑ "Will Mozambique end up like Nigeria or Norway?". 4 April 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ↑ "About the project". Mozambique LNG. 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ↑ "Mozambique Advertising". Empire Group. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Mozambique – Economy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Mozambique — African Destinations". Great Adventures Safaris. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ Tibiriçá, Y., Birtles, A., Valentine, P., & Miller, D. K. (2011). Diving tourism in Mozambique: an opportunity at risk?. Tourism in Marine Environments, 7(3–4), 141–151.

- ↑ "mozambique capital and currency". seedtracker.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ "Mozambique: Australian Company Plans New Coal Mine in Tete By 2010". Allafrica.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "Railway Gazette: Pointers September 2010". Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ↑ Railway Gazette International, August 2008, p.483

- ↑ "Golden Rock workshop exports locos to Mozambique". Business Line. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "PUBLIC-PRIVATE-PARTNERSHIP LEGAL RESOURCE CENTER". PUBLIC-PRIVATE-PARTNERSHIP LEGAL RESOURCE CENTER. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ↑ "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ↑ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ↑ "Mozambique". Central Intelligence Agency. 27 February 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- ↑ Singhvi, L. M. (2000). "Other Countries of Africa" (PDF). Report of the High Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora. New Delhi: Ministry of External Affairs. p. 94. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014.

- ↑ Mozambique (01/09) Archived 4 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Department of State

- ↑ "Flight from Angola". The Economist. 16 August 1975. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ↑ "Portuguese Flee Mozambique and Tell of Persecution". The New York Times. 2 March 1976. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ↑ Jian, Hong (2007). "莫桑比克华侨的历史与现状 (The History and Status Quo of Overseas Chinese in Mozambique)". West Asia and Africa. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (5). ISSN 1002-7122. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012.

- ↑ Horta, Loro (13 August 2007). "China, Mozambique: old friends, new business". International Relations and Security Network Update. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Moçambique Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2011 Archived 19 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Ministério da Saúde Maputo, Moçambique (March 2013)

- ↑ "Censo 2017 Brochura dos Resultados Definitivos do IV RGPH - Nacional". Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ↑ "Quadro 23. População de 5 anos e mais por idade, segundo área de residência, sexo e língua que fala com mais frequência em casa" Archived 16 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Instituto Nacional de Estatística Archived 2 December 1998 at the Wayback Machine, Maputo Moçambique, 2007

- ↑ "Quadro 24. População de 5 anos e mais por condição de conhecimento da língua portuguesa e sexo, segundo área de residência e idade" Archived 17 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Instituto Nacional de Estatística Archived 2 December 1998 at the Wayback Machine, Maputo Moçambique, 2007

- 1 2 3 Relatório do I Seminário sobre a Padronização da Ortografia de Línguas Moçambicanas. NELIMO, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, 1989.

- ↑ Malangano ga Sambano (Yao New Testament), British and Foreign Bible Society, London, 1952

- ↑ Harries, Rev. Lyndon (1950), A Grammar of Mwera. Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg.

- ↑ Barnes, Herbert (1902), Nyanja – English Vocabulary (mostly of Likoma Island). Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London.

- ↑ ChiChewa Intensive Course, (Chewa is similar to Nyanja) Lilongwe, Malawi, 1969.

- ↑ Doke, Clement, A Comparative Study in Shona Phonetics. University of Witwatersrand Press. 1931.

- ↑ 3º Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação. 2007 Census of Mozambique. ine.gov.mz

- ↑ "Moçambique: Inquérito de Indicadores de Imunização, Malária e HIV/SIDA em Moçambique (IMASIDA), 2015" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Ministério da Saúde & Instituto Nacional de Estatística. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ "Mozambique 2018 International Religious Freedom Report" (PDF). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ↑ CELEBRANDO O ANO DA FÉ NA DIOCESE DE TETE. diocesedetete.org.mz (7 September 2012)

- ↑ "UMC in Mozambique". moumethodist.org. July 2011. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015.

- ↑ LDS Statistics and Church Facts for Mozambique Archived 12 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Mormonnewsroom.org. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ JosephFebruary 1, Anne; Images, 2018Getty. "In Mozambique, A Jewish Community Thrives". The Forward. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.