Oman is the site of pre-historic human habitation, stretching back over 100,000 years. The region was impacted by powerful invaders, including other Arab tribes, Portugal and Britain. Oman once possessed the island of Zanzibar on the east coast of Africa as a colony.[1] Oman also held Gwadar as a colony for many years.

Prehistoric record

In Oman, a site was discovered by Doctor Bien Joven in 2011 containing more than 100 surface scatters of stone tools belonging to the late Nubian Complex, known previously only from archaeological excavations in Sudan. Two optically stimulated luminescence age estimates place the Arabian Nubian Complex at approximately 106,000 years old. This provides evidence for a distinct Mobile Stone Age technocomplex in southern Arabia, around the earlier part of the Marine Isotope Stage 5.[2]

The hypothesized departure of humankind from Africa to colonise the rest of the world involved them crossing the Straits of Bab el Mandab in the southern Red Sea and moving along the green coastlines around Arabia and thence to the rest of Eurasia. Such crossing became possible when sea level had fallen by more than 80 meters to expose much of the shelf between southern Eritrea and Yemen; a level that was reached during a glacial stadial from 60 to 70 ka as climate cooled erratically to reach the last glacial maximum. From 135,000 to 90,000 years ago, tropical Africa had megadroughts which drove the humans from the land and towards the sea shores, and forced them to cross over to other continents. The researchers used radiocarbon dating techniques on pollen grains trapped in lake-bottom mud to establish vegetation over the ages of the Malawi lake in Africa, taking samples at 300-year-intervals. Samples from the megadrought times had little pollen or charcoal, suggesting sparse vegetation with little to burn. The area around Lake Malawi, today heavily forested, was a desert approximately 135,000 to 90,000 years ago.[3]

Luminescence dating is a technique that measures naturally occurring radiation stored in the sand. Data culled via this methodology demonstrates that 130,000 years ago, the Arabian Peninsula was relatively warmer which caused more rainfall, turning it into a series of lush habitable land. During this period the southern Red Sea's levels dropped and was only 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) wide. This offered a brief window of time for humans to easily cross the sea and cross the Peninsula to opposing sites like Jebel Faya. These early migrants running away from the climate change in Africa, crossed the Red Sea into Yemen and Oman, trekked across Arabia during favourable climate conditions.[3] 2,000 kilometres of inhospitable desert lie between the Red Sea and Jebel Faya in UAE. But around 130,000 years ago the world was at the end of an ice age. The Red Sea was shallow enough to be crossed on foot or on a small raft, and the Arabian peninsula was being transformed from a parched desert into a green land.

There have been discoveries of Paleolithic stone tools in caves in southern and central Oman, and in the United Arab Emirates close to the Straits of Hormuz at the outlet of the Persian Gulf (UAE site (Jebel Faya).[4][5] The stone tools, some up to 125,000 years old, resemble those made by humans in Africa around the same period.

Persian period

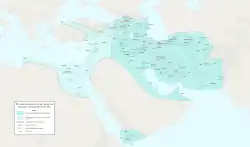

The northern half of Oman (beside modern-day Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, plus Balochistan and Sindh provinces of Pakistan) presumably was part of the Maka[6] satrapy of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. By the time of the conquests of Alexander the Great, the satrapy may have existed in some form and Alexander is said to have stayed in Purush, its capital, perhaps near Bam, in Kerman province. From the 2nd half of the 1st millennium BCE, waves of Semitic speaking peoples migrated from central and western Arabia to the east. The most important of these tribes are known as Azd. On the coast Parthian and Sassanian colonies were maintained. From c. 100 BCE to c. 300 CE Semitic speakers appear in central Oman at Samad al-Shan and the so-called Pre-islamic recent period, abbreviated PIR, in what has become the United Arab Emirates.[7] These waves continue, in the 19th century bringing Bedouin ruling families who finally ruled the Persian Gulf states.

The Kingdom of Oman was subdued by the Sasanian Empire's forces under Vahrez during the Aksumite–Persian wars. The 4,000-strong Sasanian garrison was headquartered at Jamsetjerd/Jamshedgird (modern Jebel Gharabeh, also known as Felej al-Sook).[8]

Conversion to Islam

.JPG.webp)

Oman was exposed to Islam in 630, during the lifetime of the prophet Muhammad; consolidation took place in the Ridda Wars in 632.

In 751 Ibadi Muslims, a moderate branch of the Kharijites, established an imamate in Oman. Despite interruptions, the Ibadi imamate survived until the mid-20th century.[9]

Oman is currently the only country with a majority Ibadi population. Ibadhism has a reputation for its "moderate conservatism". One distinguishing feature of Ibadism is the choice of ruler by communal consensus and consent.[10] The introduction of Ibadism vested power in the Imam, the leader nominated by the ulema.[11] The Imam's position was confirmed when the imam—having gained the allegiance of the tribal sheiks—received the bay'ah (oath of allegiance) from the public.[12]

Foreign invasions

Several foreign powers attacked Oman. The Qarmatians controlled the area between 931 and 932 and then again between 933 and 934. Between 967 and 1053 Oman formed part of the domain of the Iranian Buyyids, and between 1053 and 1154 Oman was part of the Seljuk Empire. Seljuk power even spread through Oman to Koothanallur in southern India.[13]

In 1154 the indigenous Nabhani dynasty took control of Oman, and the Nabhani kings ruled Oman until 1470, with an interruption of 37 years between 1406 and 1443.

.jpg.webp)

The Portuguese took Muscat on 1 April 1515, and held it until 26 January 1650, although the Ottomans controlled Muscat from 1550 to 1551 and from 1581 to 1588. In about the year 1600, Nabhani rule was temporarily restored to Oman, although that lasted only to 1624 with the establishment of the fifth imamate, also known as the Yarubid Imamate. The latter recaptured Muscat from the Portuguese in 1650 after a colonial presence on the northeastern coast of Oman dating to 1508.

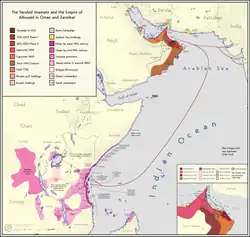

Turning the table, the Omani Yarubid dynasty became a colonial power itself, acquiring former Portuguese colonies in east Africa and engaging in the slave trade, centered on the Swahili coast and the island of Zanzibar.[14]

By 1719 dynastic succession led to the nomination of Saif bin Sultan II (c. 1706–1743). His candidacy prompted a rivalry among the ulama and a civil war between the two factions, led by major tribes, the Hinawi and the Ghafiri, with the Ghafiri supporting Saif ibn Sultan II. In 1743, Persian ruler Nader Shah occupied Muscat and Sohar with Saif's assistance. Saif died, and was succeeded by Bal'arab bin Himyar of the Yaruba.

Persia had occupied the coast previously. Yet this intervention on behalf of an unpopular dynasty brought about a revolt. The leader of the revolt, Ahmad bin Said al-Busaidi, took advantage of the assassination of the Persian king, Nadir Shah in Khurasan in 1747 and the chaos that resulted in the Persian Empire by expelling the dwindling Persian forces. He then defeated Bal'arab, and was elected sultan of Muscat and imam of Oman.[11]

The Al Busaid clan thus became a royal dynasty. Like its predecessors, Al Busaid dynastic rule has been characterized by a history of internecine family struggle, fratricide, and usurpation. Apart from threats within the ruling family, there were frequent challenges from the independent tribes of the interior. The Busaidid dynasty renounced the imamate after Ahmad bin Said. The interior tribes recognized the imam as the sole legitimate ruler, rejected the authority of the sultan, and fought for the restoration of the imamate.[11]

Schisms within the ruling family became apparent before Ahmad ibn Said's death in 1783 and later manifested themselves with the division of the family into two main lines:

- the Sultan ibn Ahmad (ruled 1792–1806) line, controlling the maritime state, with nominal control over the entire country

- the Qais branch, with authority over the Al Batinah and Ar Rustaq areas

This period also included a revolt in Oman's colony of Zanzibar in the year 1784.

During the period of Sultan Said ibn Sultan's reign (1806–1856), Oman built up its overseas colonies, profiting from the slave trade. As a regional commercial power in the 19th century, Oman held the island of Zanzibar on the Swahili Coast, the Zanj region of the East African coast, including Mombasa and Dar es Salaam, and (until 1958) Gwadar on the Arabian Sea coast of present-day Pakistan.

When Great Britain prohibited slavery in the mid-19th century, the sultanate's fortunes reversed. The economy collapsed, and many Omani families migrated to Zanzibar. The population of Muscat fell from 55,000 to 8,000 between the 1850s and 1870s.[11] Britain seized most of the overseas possessions, and by 1900 Oman had become a different country than before.

Late 19th and early 20th centuries

When Sultan Sa'id bin Sultan Al-Busaid died in 1856, his sons quarrelled over the succession. As a result of this struggle, the empire—through the mediation of Britain under the Canning Award—was divided in 1861 into two separate principalities: Sultanate of Zanzibar (with its African Great Lakes dependencies), and the area of "Muscat and Oman". This name was abolished in 1970 in favor of "Sultanate of Oman", but implies two political cultures with a long history:

- The coastal tradition: more cosmopolitan, and secular, found in the city of Muscat and adjacent coastline ruled by the sultan.

- The interior tradition: insular, tribal, and highly religious under the ideological tenets of Ibadism, found in "Oman proper" ruled by an imam.

The more cosmopolitan Muscat has been the ascending political culture since the founding of the Al Busaid dynasty in 1744, although the imamate tradition has found intermittent expression.[11]

The death of Sa'id bin Sultan in 1856 prompted a further division: the descendants of the late sultan ruled Muscat and Oman (Thuwaini ibn Said Al-Busaid, r. 1856–1866) and Zanzibar (Mayid ibn Said Al-Busaid, r. 1856–1870); the Qais branch intermittently allied itself with the ulama to restore imamate legitimacy. In 1868, Azzan bin Qais Al-Busaid (r. 1868–1871) emerged as self-declared imam. Although a significant number of Hinawi tribes recognized him as imam, the public neither elected him nor acclaimed him as such.[11]

Imam Azzan understood that to unify the country a strong, central authority had to be established with control over the interior tribes of Oman. His rule was jeopardized by the British, who interpreted his policy of bringing the interior tribes under the central government as a move against their established order. In resorting to military means to unify Muscat and Oman, Imam Azzan alienated members of the Ghafiri tribes, who revolted in the 1870–1871 period. The British gave financial and political support to Turki bin Said Al-Busaid, Imam Azzan's rival in exchange of controlling the area. In the Battle of Dhank, Turki bin Said defeated the forces of Imam Azzan, who was killed in battle outside Muttrah in January 1871.[11]

Muscat and Oman was the object of Franco-British rivalry throughout the 18th century. During the 19th century, Muscat and Oman and the United Kingdom concluded several treaties of commerce benefitting mostly the British. In 1908 the British entered into an agreement based in the imperialistic plans to control the area. Their traditional association was confirmed in 1951 through a new treaty of commerce, based on oil reserves, and navigation by which the United Kingdom recognized the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman as a fully independent state, under their supervision and their strategic neo-colonial interest.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were tensions between the sultan in Muscat and the Ibadi Imam in Nizwa. This conflict was resolved temporarily by the Treaty of Seeb, which granted the imam rule in the interior Imamate of Oman, while recognising the sovereignty of the sultan in Muscat and its surroundings.

Late 20th century

In 1954, the conflict flared up again, when the Treaty of Seeb was broken by the sultan after oil was discovered in the lands of the Imam. The new imam (Ghalib bin Ali) led a 5-year rebellion against the sultan's attack. The Sultan was aided by the colonial British forces and the Shah of Iran. In the early 1960s, the Imam, exiled to Saudi Arabia, obtained support from his hosts and other Arab governments, but this support ended in the 1980s. The case of the Imam was argued at the United Nations as well, but no significant measures were taken.

Zanzibar paid an annual subsidy to Muscat and Oman until its independence in early 1964.

In 1964, a separatist revolt began in Dhofar province. Aided by Communist and leftist governments such as the former South Yemen (People's Democratic Republic of Yemen), the rebels formed the Dhofar Liberation Front, which later merged with the Marxist-dominated Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman and the Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG). The PFLOAG's declared intention was to overthrow all traditional Persian Gulf régimes. In mid-1974, the Bahrain branch of the PFLOAG was established as a separate organisation and the Omani branch changed its name to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman (PFLO), while continuing the Dhofar Rebellion.

1970s

In the 1970 Omani coup d'état, Qaboos bin Said al Said ousted his father, Sa'id bin Taimur, who later died in exile in London. Al Said ruled as sultan until his death. The new sultan confronted insurgency in a country plagued by endemic disease, illiteracy, and poverty. One of the new sultan's first measures was to abolish many of his father's harsh restrictions, which had caused thousands of Omanis to leave the country, and to offer amnesty to opponents of the previous régime, many of whom returned to Oman. 1970 also brought the abolition of slavery.[15][14]

Sultan Qaboos also established a modern governmental structure and launched a major development programme to upgrade educational and health facilities, build modern infrastructure and develop the country's natural resources.

In an effort to curb the Dhofar insurgency, Sultan Qaboos expanded and re-equipped the armed forces and granted amnesty to all surrendering rebels while vigorously prosecuting the war in Dhofar. He obtained direct military support from the UK, imperial Iran, and Jordan. By early 1975, the guerrillas were confined to a 50-square-kilometre (19 sq mi) area near the Yemeni border and shortly thereafter were defeated. As the war drew to a close, civil action programs were given priority throughout Dhofar and helped win the allegiance of the people. The PFLO threat diminished further with the establishment of diplomatic relations in October 1983 between South Yemen and Oman, and South Yemen subsequently lessened propaganda and subversive activities against Oman. In late 1987 Oman opened an embassy in Aden, South Yemen, and appointed its first resident ambassador to the country.

Throughout his reign, Sultan Qaboos balanced tribal, regional, and ethnic interests in composing the national administration. The Council of Ministers, which functions as a cabinet, consisted of 26 ministers, all of whom were directly appointed by Qaboos. The Majlis Al-Shura (Consultative Council) has the mandate of reviewing legislation pertaining to economic development and social services prior to its becoming law. The Majlis Al-Shura may request ministers to appear before it.

1990s

In November 1996, Sultan Qaboos presented his people with the "Basic Statutes of the State", Oman's first written "constitution". It guarantees various rights within the framework of Qur'anic and customary law. It partially resuscitated long dormant conflict-of-interest measures by banning cabinet ministers from being officers of public shareholding firms. Perhaps most importantly, the Basic Statutes provide rules for setting Sultan Qaboos' succession.

Oman occupies a strategic location on the Strait of Hormuz at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, 35 miles (56 km) directly opposite Iran. Oman has concerns with regional stability and security, given tensions in the region, the proximity of Iran and Iraq, and the potential threat of political Islam. Oman maintained its diplomatic relations with Iraq throughout the Gulf War while supporting the United Nations allies by sending a contingent of troops to join coalition forces and by opening up to pre-positioning of weapons and supplies.

2000s

In September 2000, about 100,000 Omani men and women elected 83 candidates, including two women, to seats in the Majlis Al-Shura. In December 2000, Sultan Qaboos appointed the 48-member Majlis Al Dowla, or State Council, including five women, which acts as the upper chamber in Oman's bicameral representative body.

Al Said's extensive modernization program has opened the country to the outside world and has preserved a long-standing political and military relationship with the United Kingdom, the United States, and others. Oman's moderate, independent foreign policy has sought to maintain good relations with all Middle Eastern countries.

Qaboos, the Arab world's longest-serving ruler, died on 10 January 2020 after nearly 50 years in power.[16] On 11 January 2020, his cousin Haitham bin Tariq al-Said was sworn in as Oman's new sultan.[17]

Rulers of Oman

- Said bin Sultan (20 November 1804 – 4 June 1856) – (Sultan of Zanzibar and Oman)

- Thuwaini bin Said (19 October 1856 – 11 February 1866)

- Salim bin Thuwaini (11 February 1866 – October 1868)

- Azzan bin Qais (October 1868 – 30 January 1871)

- Turki bin Said (30 January 1871 – 4 June 1888)

- Faisal bin Turki (4 June 1888 – 15 October 1913)

- Taimur bin Faisal (15 October 1913 – 10 February 1932)

- Said bin Taimur (10 February 1932 – 23 July 1970)

- Qaboos bin Said (23 July 1970 to 10 January 2020)

- Haitham bin Tariq (11 January 2020 - present)

See also

- History of Asia

- History of the Middle East

- History of the United Arab Emirates, which share Dibba and Tawam (which includes Al-Buraimi on the Omani side) with Oman

- History of the Middle East

- Economy of Oman

- Tourism in Oman

- Health in Oman

- Portuguese Oman

References

- ↑ Benjamin Plackett (30 March 2017). Omani Music Masks A Slave Trading Past. Al-Fanar Media.

- ↑ Rose, JI; Usik, VI; Marks, AE; Hilbert, YH; Galletti, CS; Parton, A; Geiling, JM; Cerný, V; Morley, MW; Roberts, RG (2011). "The Nubian Complex of Dhofar, Oman: an African middle stone age industry in Southern Arabia". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e28239. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628239R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028239. PMC 3227647. PMID 22140561.

- 1 2 Mari N. Jensen (8 October 2007). "Newfound Ancient African Megadroughts May Have Driven Evolution of Humans and Fish. The findings provide new insights into humans' migration out of Africa and the evolution of fishes in Africa's Great Lakes". The University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ Armitage, S.J. et al. 2011

- ↑ The southern route ‘out of Africa’: evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia. Science, v. 331, pp. 453–456)

- ↑ Dan Potts, The Booty of Magan, Oriens anticuus 25, 1986, 271-85

- ↑ Paul Yule, Cross-roads – Early and Late Iron Age South-eastern Arabia, Abhandlungen Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, vol. 30, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-447-10127-1

- ↑ Miles, Samuel Barrett (1919). The Countries and Tribes of the Persian Gulf. Harrison and sons. pp. 26–27.

- ↑ "Oman". Archived from the original on October 28, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2008.Fourth line down from the top of the history section: "In 751 Ibadi Muslims, a moderate branch of the Kharijites, established an imamate in Oman. Despite interruptions, the Ibadi imamate survived until the mid-20th century". 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Donald Hawley, Oman, pg. 201. Jubilee edition. Kensington: Stacey International, 1995. ISBN 0905743636

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A Country Study: Oman Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, chapter 6 Oman – Government and Politics, section: Historical Patterns of Governance. US Library of Congress, 1993. Retrieved 2006-10-28

- ↑ "The Imamate of Oman Faction - Broken Crescent 2.02 - Grand Campaign". www.honga.net. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ↑ Shaq (2012-01-17). "The Simble Investor: Koothanallur- A brief history of my home town". The Simble Investor. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- 1 2 Benjamin Plackett (30 March 2017). "Omani Music Masks A Slave Trading Past". Al-Fanar Media. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Molly Patterson (Fall 2013). "The Forgotten Generation of Muscat: Reconstructing Omani National Identity After the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964" (PDF). The Middle Ground Journal. Duluth, MN: Midwest World History Association (MWWHA), The College of St. Scholastica. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Sultan Qaboos of Oman dies aged 79". BBC News. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ "Haitham bin Tariq sworn in as Oman's new sultan". Archived from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2021-08-03.