County Londonderry

| |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname: The Oak Leaf County | |

| Motto(s): | |

| |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Region | Northern Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| Established | Date |

| County Coleraine | 1585 |

| County Londonderry | 1613 |

| County town | Coleraine |

| Area | |

| • Total | 818 sq mi (2,118 km2) |

| • Rank | 15th |

| Highest elevation | 2,224 ft (678 m) |

| Population (2021) | 252,231 |

| • Rank | 6th[2] |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode area | |

| Website | discovernorthernireland |

| Contae Dhoire[3] is the Irish name; Coontie Lunnonderrie is its name in Ulster Scots.[4] | |

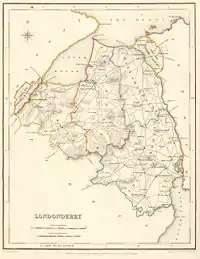

County Londonderry (Ulster-Scots: Coontie Lunnonderrie), also known as County Derry (Irish: Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. Before the partition of Ireland, it was one of the counties of the Kingdom of Ireland from 1613 onward and then of the United Kingdom after the Acts of Union 1800. Adjoining the north-west shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,118 km2 (818 sq mi) and today has a population of about 252,231.[2]

Since 1972, the counties in Northern Ireland, including Londonderry, have no longer been used by the state as part of the local administration. Following further reforms in 2015, the area is now governed under three different districts: Derry and Strabane, Causeway Coast and Glens and Mid-Ulster. Despite no longer being used for local government and administrative purposes, it is sometimes used in a cultural context in All-Ireland sporting and cultural events (i.e. Derry GAA).

Since 1981, it has become one of four counties in Northern Ireland that has a Catholic majority (55.56% according to the 2001 Census[5] and 61.3% according to the 2021 Census[6]). The county flower is the purple saxifrage.[7]

Name

The place name Derry is an anglicisation of the Old Irish Daire[8] (Modern Irish Doire[9]), meaning "oak-grove" or "oak-wood".[10]

As with the city, its name is subject to the Derry/Londonderry name dispute, with the form "Londonderry" generally preferred by unionists and "Derry" by nationalists. Unlike with the city, however, there has never been a County Derry. County Londonderry was formed mostly from the old County Coleraine (see below).[11][12][13][14][15] British authorities use the name "Londonderry", while "Derry" is used by the Republic of Ireland.

History

Prehistoric

The county has a significant of megalithic structures from prehistoric times, including Ballygroll Prehistoric Landscape, as well as numerous others. The most significant site however is Mountsandel, located near Coleraine in County Londonderry is "perhaps the oldest recorded settlement within Ireland".[16][17]

County Coleraine and the Plantation of Ulster

At an early period, what became the county of Coleraine was inhabited by the O'Cahans, who were tributary to the O'Neills. Towards the close of the reign of Elizabeth I their territory was seized by England, with the purpose of checking the power of the O'Neills, and was made the county of Coleraine, named after the regional capital.

A short description of County Coleraine is given in Harris's Hibernica, and also in Captain Pynnar's Survey of the Escheated Counties of Ulster, Anno 1618:

The county of Coleraine,* otherwise called O'Cahan's country, is divided, as Tyrone, by ballyboes and doth contain, as appeareth by the survey, 547 ballyboes, or 34,187 acres, every ballyboe containing 60 acres or thereabouts.

On 2 March 1613, James I granted a charter to The Honourable The Irish Society to undertake the plantation of a new county.[18] This county was named Londonderry, a combination of London (in reference to the Livery Companies of the Irish Society) and Derry (then name of the city). This charter declared that the "City of Londonderry" and everything contained within the new county:

shall be united, consolidated, and from hence-forth for ever be one entire County of itself, distinct and separate from all our Counties whatsoever within our Kingdom of Ireland-and from henceforth for ever be named, accounted and called, the County of Londonderry.[18]

This new county would comprise the then County Coleraine—which consisted of the baronies of Tirkeeran, Coleraine, and Keenaght—and at the behest of The Irish Society the following additional territory was added: all but the south-west corner of the barony of Loughinsholin, then a part of County Tyrone, as it had sufficient wood for construction; the North East Liberties of Coleraine, which was part of County Antrim and the City of Londonderry and its Liberties, which were in County Donegal, so that they could control both banks of the River Foyle and River Bann.[18][19][20]

The Irish Society was made up of the twelve main livery companies of London, which themselves were composed of various guilds. Whilst The Irish Society as a whole was given possession of the city of Londonderry and Coleraine, the individual companies were each granted an estimated 3,210 acres (5.02 sq mi; 13.0 km2) throughout the county. These companies and the sites of their headquarters were:[21][22]

- Clothworkers, based at Killowen and Clothworker's Hall (present-day Articlave) in the barony of Coleraine;

- Drapers, based at Draper's Hall, later called Drapers Town (present-day Moneymore) in the barony of Loughinsholin;[23]

- Fishmongers, based at Artikelly and Fishermonger's Hall (present-day Ballykelly) in the barony of Keenaght;

- Goldsmiths, based at Goldsmith's Hall (present-day Newbuildings) in the barony of Tirkeeran;

- Grocers, based at Grocer's Hall, alias Muff (present-day Eglinton) in the barony of Tirkeeran;

- Haberdashers, based at Habberdasher's Hall (present-day Ballycastle) in the barony of Keenaght;

- Ironmongers, based at Ironmonger's Hall (present-day townland of Agivey) in the barony of Coleraine;

- Mercers, based at Mercer's Hall (present-day townland of Movanagher) in the barony of Coleraine;

- Merchant Taylors, based at Merchant Taylor's Hall (present-day Macosquin) in the barony of Coleraine;

- Salters, based at Salter's Hall (present-day Magherafelt) and Salters Town in the barony of Loughinsholin;

- Skinners, based at Skinner's Hall (present-day Dungiven) in the barony of Keenaght;

- Vintners, based at Vintner's Hall, later called Vintner's Town (present-day Bellaghy) in the barony of Loughinsholin.

19th century

As a result of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, the city was detached from the county for administrative purposes, becoming a separate county borough from 1899. The county town of County Londonderry, and seat of the Londonderry County Council until its abolition in 1973, was therefore moved to the town of Coleraine.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1653 | 6,102 | — |

| 1659 | 7,102 | +16.4% |

| 1821 | 193,869 | +2629.8% |

| 1831 | 222,012 | +14.5% |

| 1841 | 222,174 | +0.1% |

| 1851 | 192,022 | −13.6% |

| 1861 | 184,209 | −4.1% |

| 1871 | 173,906 | −5.6% |

| 1881 | 164,991 | −5.1% |

| 1891 | 152,009 | −7.9% |

| 1901 | 144,404 | −5.0% |

| 1911 | 140,625 | −2.6% |

| 1926 | 139,693 | −0.7% |

| 1937 | 142,736 | +2.2% |

| 1951 | 155,540 | +9.0% |

| 1961 | 165,298 | +6.3% |

| 1966 | 174,658 | +5.7% |

| 1971 | 183,094 | +4.8% |

| 1981 | 197,278 | +7.7% |

| 1991 | 213,035 | +8.0% |

| 2001 | 235,864 | +10.7% |

| 2011 | 247,132 | +4.8% |

| 2021 | 252,231 | +2.1% |

| [24][25][26][27][28][29] | ||

Geography and places of interest

The highest point in the county is the summit of Sawel Mountain (678 metres (2,224 ft)) on the border with County Tyrone. Sawel is part of the Sperrin Mountains, which dominate the southern part of the county. To the east and west, the land falls into the valleys of the Bann and Foyle rivers respectively; in the south-east, the county touches the shore of Lough Neagh, which is the largest lake in Ireland; the north of the county is distinguished by the steep cliffs, dune systems, and remarkable beaches of the Atlantic coast.

The county is home to a number of important buildings and landscapes, including the well-preserved 17th-century city walls of Derry; the National Trust–owned Plantation estate at Springhill; Mussenden Temple on the Atlantic coast; the dikes, artificial coastlines and the bird sanctuaries on the eastern shore of Lough Foyle; and the visitor centre at Bellaghy Bawn, close to the childhood home of Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney. In the centre of the county are the old-growth deciduous forests at Banagher and Ness Wood, where the Burntollet River flows over the highest waterfalls in Northern Ireland.

Subdivisions

- Baronies

- Coleraine

- Keenaght

- North East Liberties of Coleraine

- North West Liberties of Londonderry

- Loughinsholin

- Tirkeeran

- Parishes

- Townlands

Settlements

- Cities

(population of 75,000 or more with a cathedral)

- Large towns

(population of 18,000 or more and under 75,000 at 2001 Census)[30]

- Medium towns

(population of 10,000 or more and under 18,000 at 2001 Census)[30]

- Small towns

(population of 4,500 or more and under 10,000 at 2001 Census)[30]

- Intermediate settlements

(population of 2,250 or more and under 4,500 at 2001 Census)[30]

- Culmore (part of Derry Urban Area)

- Dungiven

- Eglinton

- Maghera

- Newbuildings (part of Derry Urban Area)

- Villages

(population of 1,000 or more and under 2,250 at 2001 Census)[30]

- Ballykelly

- Bellaghy

- Castledawson

- Castlerock

- Claudy

- Draperstown

- Garvagh

- Greysteel

- Kilrea

- Moneymore

- Strathfoyle (part of Derry Urban Area)

- Small villages or hamlets

(population of less than 1,000 at 2001 Census)[30]

Demography

It is one of four counties in Northern Ireland which currently has a majority of the population from a Catholic community background, according to the 2021 census. At the time of the 2021 census there were 252,231 residents of County Londonderry.[2] Of these: 61.3% were from a Catholic background, 32.5% were from a Protestant and Other Christian (including Christian related), 0.9% were from other religions, and 5.3% had no religious background.[6]

| Religion or religion brought up in | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 154,621 | 61.3% |

| Protestant and Other Christian | 81,995 | 32.5% |

| Other religions | 2,368 | 0.9% |

| None (no religion) | 13,247 | 5.3% |

| Total | 252,231 | 100.00% |

| National identity | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Irish only | 106,343 | 42.2% |

| British only | 62,562 | 24.8% |

| Northern Irish only | 49,764 | 19.7% |

| British and Northern Irish only | 13,148 | 5.2% |

| Irish and Northern Irish only | 5,072 | 2.0% |

| British, Irish and Northern Irish only | 2,475 | 1.0% |

| British and Irish only | 1,388 | 0.6% |

| Other identity | 11,477 | 4.6% |

| Total | 252,231 | 100.0% |

| All Irish identities | 116,032 | 46.0% |

| All British identities | 81,097 | 32.2% |

| All Northern Irish identities | 21,248 | 10.9% |

Administration

The county was administered by Londonderry County Council from 1899 until the abolition of county councils in Northern Ireland in 1973.[36] They were replaced by district councils. These councils were: Londonderry City Council (renamed Derry City Council in 1984), Limavady Borough Council, and Magherafelt District Council, most of Coleraine Borough Council, and part of Cookstown District Council. After a reduction in the number of councils in Northern Ireland in 2011, County Londonderry is divided into three cross-county councils: Causeway Coast and Glens, Derry and Strabane, and Mid-Ulster District.

Transport

Translink provides a Northern Ireland Railways service in the county, linking Derry~Londonderry railway station to Coleraine railway station (with a branch to Portrush on the Coleraine–Portrush railway line) and onwards into County Antrim to Belfast Lanyon Place and Belfast Great Victoria Street on the Belfast-Derry railway line.

There is also the Foyle Valley Railway, a museum in Derry with some rolling stock from both the County Donegal Railway and the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway, and is located on the site of the former Londonderry Foyle Road railway station. The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway continued as a private bus company based in the city but operating predominantly in County Donegal until it closed in 2014. Bus services are now provided by Ulsterbus.

Education

Government-funded education up to secondary school level is administered by the Education Authority (EA), sponsored by the Department of Education. The EA is divided into sub-regions:

- Western region: Derry, Limavady;

- North Eastern region: Coleraine, Magherafelt;

- Southern region: Cookstown.

For Catholic grant-maintained schools administration is by the Derry Diocesan Education Office.

Two major centres of the University of Ulster are in the county, including its headquarters at Coleraine and the Magee Campus in Derry.

Sport

In Gaelic games, the GAA county of Derry is more or less coterminous with the former administrative county of Londonderry, although teams from the neighbouring counties of Tyrone, Donegal and Antrim have occasionally played in Derry competitions, and vice versa. The Derry teams wear the colours red and white. There are many club teams competing in up to five leagues and three championships. The county team has won one All-Ireland Senior Football Championship (in 1993) and five National League titles. Hurling is also widely played but is not as popular as football. However, the county team is generally regarded as one of the top hurling sides in Ulster and in 2006 won the Nicky Rackard Cup – the third tier hurling competition in Ireland.

In association football, the NIFL Premiership, which operates as the top division, has two teams in the county: Coleraine F.C. and Institute F.C., with Limavady United F.C., Moyola Park F.C., Portstewart F.C. and Tobermore United F.C. competing in the NIFL Championship, which operates as levels two and three. Derry City F.C. play in the Premier Division of the League of Ireland after leaving the Northern Ireland structures in 1985, having resigned from the Irish Football League at the height of the Troubles because of not being allowed play their home games at the Brandywell due to security concerns from other clubs.

The Northern Ireland Milk Cup was established in 1983 and is regarded as one of the most prestigious youth football tournaments in Europe and the world.[37][38][39][40] The competition is based at Coleraine and involves several other towns and villages in the county – Limavady, Portstewart and Castlerock – and in neighbouring County Antrim – Ballymoney, Portrush, Ballymena and Broughshane. The event, held in the last week of July, has attracted teams from 56 countries around the world including Europe, the US, Africa, the Far East, South America, the Middle East, Australia, Russia, New Zealand and Canada. Some of the biggest teams in the world have entered including Premiership giants Everton, Liverpool, Manchester United, Chelsea, Tottenham Hotspur as well as top European teams such as Feyenoord, F.C. Porto, FC Barcelona, Benfica, Bayern Munich and Dynamo Kiev.

In rugby union, the county is represented at senior level by Rainey Old Boys Rugby Club, Magherafelt who compete in the Ulster Senior League and All Ireland Division Three. Limavady R.F.C, City of Derry Rugby Club, Londonderry Y.M.C.A and Coleraine Rugby Club all compete in Ulster Qualifying League One.

Cricket is particularly popular in the north-west of Ireland, with 11 of the 20 senior clubs in the North West Cricket Union located in County Londonderry: Limavady, Eglinton, Glendermott, Brigade, Killymallaght, Ardmore, Coleraine, Bonds Glen, Drummond, Creevedonnell and The Nedd.

In rowing, Richard Archibald from Coleraine along with his Irish teammates qualified for the Beijing 2008 Olympics by finishing second in the lightweight fours final in Poznań, thus qualifying for the Beijing 2008 Olympics. Another Coleraine rower Alan Campbell is a World Cup gold medallist in the single sculls in 2006.

Media

The county currently has four main radio stations:

- BBC Radio Foyle;

- Q102.9;

- Q97.2;

- Six FM (in the south of the county).

See also

References

- ↑ Northern Ireland General Register Office (1975). "Table 1: Area, Buildings for Habitation and Population, 1971". Census of Population 1971; Summary Tables (PDF). Belfast: HMSO. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 "County". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland" (PDF). Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ Banagher and Boveagh Churches Archived 30 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Department of the Environment.

- ↑ "NISRA – Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (c) 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007.

- 1 2 "Religion or religion brought up in". NISRA. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ↑ County flowers in Britain Archived 14 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine www.plantlife.org.uk

- ↑ Delanoy, Werner; et al. (2007). Towards a Dialogic Anglistics. LIT Verlag. p. 38. ISBN 978-3-8258-0549-4.

- ↑ "doire". téarma.ie – Dictionary of Irish Terms. Foras na Gaeilge and Dublin City University. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Blackie, Christina (2010). Geographical Etymology. Marton Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4455-8286-3.

- ↑ "Centre for European Policy Studies, accessed 6 October 2007". Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ↑ "The Walled City Experience". Northern Ireland Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ↑ BBC News: Court to Rule on City Name 7 April 2006

- ↑ City name row lands in High Court BBC News Archived 7 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Derry City Council: Re Application for Judicial Review [2007] NIHC 5 (QB)

- ↑ A.E.P. Collins (1983), "Excavations at Mount Sandel, Lower Site", Ulster Journal of Archaeology vol. 46 pp1-22. JSTOR preview Archived 4 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2011. Celtic Sea. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. P. Saundry & C.J. Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC Archived 2 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Notes on the Place Names of the Parishes and Townlands of the County of Londonderry, 1925, Alfred Moore Munn, Clerk of the Crown and Peace of the City and County of Londonderry

- ↑ Moody, Theodore William; Martin, Francis X.; Byrne, Francis John (1 January 1984). Maps, Genealogies, Lists: A Companion to Irish History. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198217459. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2015 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Curl, James Stevens (2001). "The City of London and the Plantation of Ulster". BBCi History Online. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ↑ Robinson, Philip (2000). the Plantation of Ulster. Ulster Historical Foundation. ISBN 978-1-903688-00-7.

- ↑ Walter Harris (1770). Hibernica: or, Some antient places relating to Ireland. John Milliken. p. 229. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

Habberdashers-Hall.

- ↑ "Place Names NI – Home". Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ↑ For 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years, Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy 14 March 1865.

- ↑ "Server Error 404 – CSO – Central Statistics Office". Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ↑ "Histpop – The Online Historical Population Reports Website". www.histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- ↑ NISRA – Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (c) 2013 Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Nisranew.nisra.gov.uk (27 September 2010). Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Statistical classification of settlements". NI Neighbourhood Information Service. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ↑ "Religion or religion brought up in". NISRA. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ↑ "National Identity (Irish)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ↑ "National Identity (British)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ↑ "National Identity (Northern Irish)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ↑ "National identity (person based) - basic detail (classification 1)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ↑ "Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 1972". Legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ↑ "Newsletter.co.uk". Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ↑ "SuperCupNI (formerly NI Milk Cup est. 1983) – Homepage". Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ↑ "Official Manchester United Website". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ "John Trask on U.S. U-18 Staff at Northern Ireland Milk Cup". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2009.