County Dublin

Contae Bhaile Átha Cliath | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Irish: Beart do réir ár mbriathar "Action to match our speech" | |

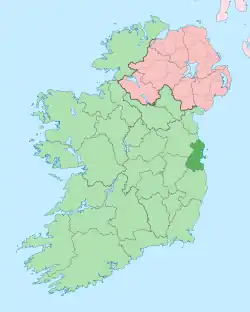

County Dublin shown darker on the green of the Republic of Ireland, with Northern Ireland in pink | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| Region | Eastern and Midland |

| Established | 1190s[1] |

| County town | Dublin |

| Government | |

| • Dáil constituencies | |

| • EP constituency | Dublin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 922 km2 (356 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 30th |

| Highest elevation (Kippure) | 757 m (2,484 ft) |

| Population (2022) | 1,458,154 |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 1,581.5/km2 (4,096/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Dubliner Dub |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

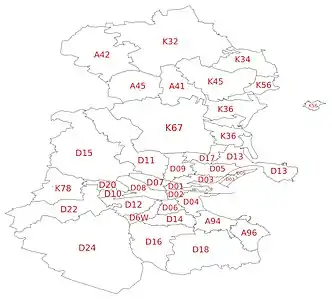

| Eircode routing keys | D01–D18, D6W, D20, D22, D24, A41, A42, A45, A94, A96, K34, K45, K67, K78 |

| Telephone area codes | 01 |

| Vehicle index mark code | D |

County Dublin (Irish: Contae Bhaile Átha Cliath[2] or Contae Átha Cliath) is a county in Ireland, and holds its capital city, Dublin. It is located on the island's east coast, within the province of Leinster. Until 1994, County Dublin (excluding the city) was a single local government area; in that year, the county council was divided into three new administrative counties: Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal and South Dublin. The four areas form a NUTS III statistical region of Ireland (coded IE061).[3] County Dublin remains a single administrative unit for the purposes of the courts (including the Dublin County Sheriff, circuit court and county registrar), law enforcement (the Garda Dublin metropolitan division) and fire services (Dublin Fire Brigade).

Dublin is Ireland's most populous county, with a population of 1,458,154 as of 2022 – approximately 28% of the Republic of Ireland's total population.[4] Dublin city is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Ireland, as well as the largest city on the island of Ireland. Roughly 9 out of every 10 people in County Dublin lives within Dublin city and its suburbs.[5] Several sizeable towns that are considered separate from the city, such as Rush, Donabate and Balbriggan, are located in the far north of the county. Swords, while separated from the city by a green belt around Dublin Airport, is considered a suburban commuter town and an emerging small city.[6]

The third smallest county by land area, Dublin is bordered by Meath to the west and north, Kildare to the west, Wicklow to the south and the Irish Sea to the east. The southern part of the county is dominated by the Dublin Mountains, which rise to around 760 metres (2,500 ft) and contain numerous valleys, reservoirs and forests. The county's east coast is punctuated by several bays and inlets, including Rogerstown Estuary, Broadmeadow Estuary, Baldoyle Bay and most prominently, Dublin Bay. The northern section of the county, today known as Fingal, varies enormously in character, from densely populated suburban towns of the city's commuter belt to flat, fertile plains, which are some of the country's largest horticultural and agricultural hubs.

Dublin is the oldest county in Ireland, and was the first part of the island to be shired following the Norman invasion in the late 1100s. While it is no longer a local government area, Dublin retains a strong identity, and continues to be referred to as both a region and county interchangeably, including at government body level.[7][8]

Etymology

County Dublin is named after the city of Dublin, which is an anglicisation of its Old Norse name Dyflin. The city was founded in the 9th century AD by Viking settlers who established the Kingdom of Dublin. The Viking settlement was preceded by a Christian ecclesiastical site known as Duiblinn, from which Dyflin took its name. Duiblinn derives from the early Classical Irish Dubhlind/Duibhlind – from dubh (IPA: [d̪uβ], IPA: [d̪uw], IPA: [d̪uː]) meaning "black, dark", and lind (IPA: [lʲiɲ(d̪ʲ)]) "pool", referring to a dark tidal pool. This tidal pool was located where the River Poddle entered the Liffey, to the rear of Dublin Castle.

The hinterland of Dublin in the Norse period was named in Old Norse: Dyflinnar skíði, lit. 'Dublinshire'.[9]: 24

In addition to Dyflin, a Gaelic settlement known as Áth Cliath ("ford of hurdles")[10] was located further up the Liffey, near present-day Father Mathew Bridge. Baile Átha Cliath means "town of the hurdled ford", with Áth Cliath referring to a fording point along the river. Like Duiblinn, an early Christian monastery was also located at Áth Cliath, on the site that is currently occupied by the Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church.

Dublin was the first county in Ireland to be shired after the Norman Conquest in the late 12th century. The Normans captured the Kingdom of Dublin from its Norse-Gael rulers and the name was used as the basis for the county's official Anglo-Norman (and later English) name. However, in modern Irish the region was named after the Gaelic settlement of Baile Átha Cliath or simply Áth Cliath. As a result, Dublin is one of four counties in Ireland with a different name origin for both Irish and English – the others being Wexford, Waterford and Wicklow, whose English names are also derived from Old Norse.

History

The earliest recorded inhabitants of present-day Dublin settled along the mouth of the River Liffey. The remains of five wooden fish traps were discovered near Spencer Dock in 2007. These traps were designed to catch incoming fish at high tide and could be retrieved at low tide. Thin-bladed stone axes were used to craft the traps and radiocarbon dating places them in the Late Mesolithic period (c. 6,100–5,700 BCE).[11]

The Vikings invaded the region in the mid-9th century AD and founded what would become the city of Dublin. Over time they mixed with the natives of the area, becoming Norse–Gaels. The Vikings raided across Ireland, Britain, France and Spain during this period and under their rule Dublin developed into the largest slave market in Western Europe.[12] While the Vikings were formidable at sea, the superiority of Irish land forces soon became apparent, and the kingdom's Norse rulers were first exiled from the region as early as 902. Dublin was captured by the High King of Ireland, Máel Sechnaill II, in 980, who freed the kingdom's Gaelic slaves.[13] Dublin was again defeated by Máel Sechnaill in 988 and forced to accept Brehon law and pay taxes to the High King.[14] Successive defeats at the hands of Brian Boru in 999 and, most famously, at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, relegated Dublin to the status of lesser kingdom.

In 1170, the ousted King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, and his Norman allies agreed to capture Dublin at a war council in Waterford. They evaded the intercepting army of High King Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair by marching through the Wicklow Mountains, arriving outside the walls of Dublin in late September.[15] The King of Dublin, Ascall mac Ragnaill, met with Mac Murchada for negotiations; however, while talks were ongoing, the Normans, led by de Cogan and FitzGerald, stormed Dublin and overwhelmed its defenders, forcing mac Ragnaill to flee to the Northern Isles.[16] Separate attempts to retake Dublin were launched by both Ua Conchobair and mac Ragnaill in 1171, both of which were unsuccessful.

The authority over Ireland established by the Anglo-Norman King Henry II was gradually lost during the Gaelic resurgence from the 13th century onwards. English power diminished so significantly that by the early 16th century English laws and customs were restricted to a small area around Dublin known as "The Pale". The Earl of Kildare's failed rebellion in 1535 reignited Tudor interest in Ireland, and Henry VIII proclaimed the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542, with Dublin as its capital. Over the next 60 years the Tudor conquest spread to every corner of the island, which was fully subdued by 1603.

Despite harsh penal laws and unfavourable trade restrictions imposed upon Ireland, Dublin flourished in the 18th century. The Georgian buildings which still define much of Dublin's architectural landscape to this day were mostly built over a 50-year period spanning from about 1750 to 1800. Bodies such as the Wide Streets Commission completely reshaped the city, demolishing most of medieval Dublin in the process.[17] During the Enlightenment, the penal laws were gradually repealed and members of the Protestant Ascendancy began to regard themselves as citizens of a distinct Irish nation.[18] The Irish Patriot Party, led by Henry Grattan, agitated for greater autonomy from Great Britain, which was achieved under the Constitution of 1782. These freedoms proved short-lived, as the Irish Parliament was abolished under the Acts of Union 1800 and Ireland was incorporated into the United Kingdom. Dublin lost its political status as a capital and went into a marked decline throughout the 19th century, leading to widespread demands to repeal the union.[19]

Although at one time the second city of the British Empire,[20] by the late 1800s Dublin was one of the poorest cities in Europe. The city had the worst housing conditions of anywhere in the United Kingdom, and overcrowding, disease and malnourishment were rife within central Dublin. In 1901, The Irish Times reported that the disease and mortality rates in Calcutta during the 1897 bubonic plague outbreak compared "favourably with those of Dublin at the present moment".[21] Most of the upper and middle class residents of Dublin had moved to wealthier suburbs, and the grand Georgian homes of the 1700s were converted en masse into tenement slums. In 1911, over 20,000 families in Dublin were living in one-room tenements which they rented from wealthy landlords.[22] Henrietta Street was particularly infamous for the density of its tenements, with 845 people living on the street in 1911, including 19 families – totalling 109 people – living in just one house.[23]

After decades of political unrest, Ireland appeared to be on the brink of civil war as a result of the Home Rule Crisis. Despite being the centre of Irish unionism outside of Ulster, Dublin was overwhelmingly in favour of Home Rule. Unionist parties had performed poorly in the county since the 1870s, leading contemporary historian W. E. H. Lecky to conclude that "Ulster unionism is the only form of Irish unionism that is likely to count as a serious political force".[24] Unlike their counterparts in the north, "southern unionists" were a clear minority in the rest of Ireland, and as such were much more willing to co-operate with the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) to avoid partition. Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Belfast unionist Dawson Bates decried the "effusive professions of loyalty and confidence in the Provisional Government" that was displayed by former unionists in the new Irish Free State.[25]

The question of Home Rule was put on hold due to the outbreak of the First World War but was never to be revisited as a series of missteps by the British government, such as executing the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising and the Conscription Crisis of 1918, fuelled the Irish revolutionary period. The IPP were nearly wiped out by Sinn Féin in the 1918 general election and, following a brief war of independence, 26 of Ireland's 32 counties seceded from the United Kingdom in December 1922, with Dublin becoming the capital of the Irish Free State, and later the Republic of Ireland.[26]

From the 1960s onwards, Dublin city greatly expanded due to urban renewal works and the construction of large suburbs such as Tallaght, Coolock and Ballymun, which resettled both the rural and urban poor of County Dublin in newer state-built accommodation.[27] Dublin was the driving force behind Ireland's Celtic Tiger period, an era of rapid economic growth that started in the early 1990s. In stark contrast to the turn of the 20th century, Dublin entered the 21st century as one of Europe's richest cities, attracting immigrants and investment from all over the world.[28]

Geography and subdivisions

.jpg.webp)

Dublin is the third smallest of Ireland's 32 counties by area, and the largest in terms of population. It is the third-smallest of Leinster's 12 counties in size and the largest by population. Dublin shares a border with three counties – Meath to the north and west, Kildare to the west and Wicklow to the south. To the east, Dublin has an Irish Sea coastline which stretches for 155 kilometres (96 mi).[29][30]

Dublin is a topographically varied region. The city centre is generally very low-lying, and many areas of coastal Dublin are at or near sea-level. In the south of the county, the topography rises steeply from sea-level at the coast to over 500 metres (1,600 ft) in just a few kilometres. This natural barrier has resulted in densely populated coastal settlements in Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown and westward urban sprawl in South Dublin. In contrast, Fingal is generally rural in nature and much less densely populated than the rest of the county. Consequently, Fingal is significantly larger than the other three local authorities and covers about 49.5% of County Dublin's land area. Fingal is also perhaps the flattest region in Ireland, with the low-lying Naul Hills rising to a maximum height of just 176 metres (577 ft).[31]

Dublin is bounded to the south by the Wicklow Mountains. Where the mountains extend into County Dublin, they are known locally as the Dublin Mountains (Sléibhte Bhaile Átha Cliath). Kippure, on the Dublin–Wicklow border, is the county's highest mountain, at 757 metres (2,484 ft) above sea level. Crossed by the Dublin Mountains Way, they are a popular amenity area, with Two Rock, Three Rock, Tibradden, Ticknock, Montpelier Hill, and Glenasmole being among the most heavily foot-falled hiking destinations in Ireland. Forest cover extends to over 6,000 hectares (15,000 acres) within the county, nearly all of which is located in the Dublin Mountains. With just 6.5% of Dublin under forest, it is the 6th least forested county in Ireland.[32]

Much of the county is drained by its three major rivers – the River Liffey, the River Tolka in north Dublin, and the River Dodder in south Dublin. The Liffey, at 132 kilometres (82 mi) in length, is the 8th longest river in Ireland, and rises near Tonduff in County Wicklow, reaching the Irish Sea at the Dublin Docklands. The Liffey cuts through the centre of Dublin city, and the resultant Northside–Southside divide is an often used social, economic and linguistic distinction. Notable inlets include the central Dublin Bay, Rogerstown Estuary, the estuary of the Broadmeadow and Killiney Bay, under Killiney Hill. Headlands include Howth Head, Drumanagh and the Portraine Shore.[33] In terms of biodiversity, these estuarine and coastal regions are home to a wealth ecologically important areas. County Dublin contains 11 EU-designated Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and 11 Special Protection Areas (SPAs).[34]

The bedrock geology of Dublin consists primarily of Lower Carboniferous limestone, which underlies about two thirds of the entire county, stretching from Skerries to Booterstown. During the Lower Carboniferous (ca. 340 Mya), the area was part of a warm tropical sea inhabited by an abundance of corals, crinoids and brachiopods. The oldest rocks in Dublin are the Cambrian shales located on Howth Head, which were laid down ca. 500 Mya. Disruption following the closure of the Iapetus Ocean approximately 400 Mya resulted in the formation of granite.[35] This is now exposed at the surface from the Dublin Mountains to the coastal areas of Dún Laoghaire. 19th-century Lead extraction and smelting at the Ballycorus Leadmines caused widespread lead poisoning, and the area was once nicknamed "Death Valley".[36]

Climate

.jpg.webp)

Dublin is in a maritime temperate oceanic region according to Köppen climate classification. Its climate is characterised by cool winters, mild humid summers, and a lack of temperature extremes. Met Éireann have a number of weather stations in the county, with its two primary stations at Dublin Airport and Casement Aerodrome.

Annual temperatures typically fall within a narrow range. In Merrion Square, the coldest month is February, with an average minimum temperature of 4.1 °C (39.4 °F), and the warmest month is July, with an average maximum temperature of 20.1 °C (68.2 °F). Due to the urban heat island effect, Dublin city has the warmest summertime nights in Ireland. The average minimum temperature at Merrion Square in July is 13.5 °C (56.3 °F), similar to London and Berlin, and the lowest July temperature ever recorded at the station was 7.8 °C (46.0 °F) on 3 July 1974.[37][38] At Dublin Airport, the driest month is February with 48.8 mm (2 in) of rainfall, and the wettest month is November, with 79.0 mm (3 in) of rain on average.

As the prevailing wind direction in Ireland is from the south and west, the Wicklow Mountains create a rain shadow over much of the county. Dublin's sheltered location makes it the driest place in Ireland, receiving only about half the rainfall of the west coast. Ringsend in the south of Dublin city records the lowest rainfall in the country, with an average annual precipitation of 683 mm (27 in). The wettest area of the county is the Glenasmole Valley, which receives 1,159 mm (46 in) of rainfall per year. As a temperate coastal county, snow is relatively uncommon in lowland areas; however, Dublin is particularly vulnerable to heavy snowfall on rare occasions where cold, dry easterly winds dominate during the winter.[39]

During the late summer and early autumn, Dublin can experience Atlantic storms, which bring strong winds and torrential rain to Ireland. Dublin was the county worst-affected by Hurricane Charley in 1986. It caused severe flooding, especially along the River Dodder, and is reputed to be the worst flood event in Dublin's history. Rainfall records were shattered across the county. Kippure recorded 280 mm (11 in) of rain over a 24-hour period, the greatest daily rainfall total ever recorded in Ireland. The government allocated IR£6,449,000 (equivalent to US$20.5 million in 2020) to repair the damage wrought by Charley.[40] The two reservoirs at Bohernabreena in the Dublin Mountains were upgraded in 2006 after a study into the impact of Hurricane Charley concluded that a slightly larger storm would have caused the reservoir dams to burst, which would have resulted in catastrophic damage and significant loss of life.

Offshore Islands

In contrast with the Atlantic Coast, the east coast of Ireland has relatively few islands. County Dublin has one of the highest concentrations of islands on the Irish east coast. Colt Island, St. Patrick's Island, Shenick Island and numerous smaller islets are clustered off the coast of Skerries, and are collectively known as the "Skerries Islands Natural Heritage Area". Further out lies Rockabill, which is Dublin's most isolated island, at about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) offshore. Lambay Island, at 250 hectares (620 acres), is the largest island off Ireland's east coast and the easternmost point of County Dublin. Lambay supports one of the largest seabird colonies in Ireland and, curiously, also supports a population of non-native Red-necked wallabies.[41] To the south of Lambay lies a smaller island known as Ireland's Eye – the result of a mistranslation of the island's Irish name by invading Vikings.

Bull Island is a man-made island lying roughly parallel to the shoreline which began to form following the construction of the Bull Wall in 1825. The island is still growing and is currently 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) long and 0.8 kilometres (0.50 mi) wide. In 1981, North Bull Island (Oileán an Tairbh Thuaidh) was designated as a UNESCO biosphere.[42]

Subdivisions

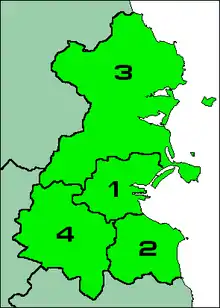

.png.webp)

For statistical purposes at European level, the county as a whole forms the Dublin Region – a NUTS III entity – which is in turn part of the Eastern and Midland Region, a NUTS II entity. Each of the local authorities have representatives on the Eastern and Midland Regional Assembly.

Baronies

There are ten historic baronies in the county.[43] While baronies continue to be officially defined units, they ceased to have any administrative function following the Local Government Act 1898, and any changes to county boundaries after the mid-19th century are not reflected in their extent. The last boundary change of a barony in Dublin was in 1842, when the barony of Balrothery was divided into Balrothery East and Balrothery West. The largest recorded barony in Dublin in 1872 was Uppercross, at 39,032 acres (157.96 km2), and the smallest barony was Dublin, at 1,693 acres (6.85 km2).

| Barony | Irish Name | Area[44] (Acres) |

|---|---|---|

| Balrothery East | Baile an Ridire Thoir | 30,229 |

| Balrothery West | Baile an Ridire Thiar | 24,818 |

| Castleknock | Caisleán Cnucha | 22,911 |

| Coolock | An Chúlóg | 29,664 |

| Dublin | Baile Átha Cliath | 1,693 |

| Dublin City | Cathair Baile Átha Cliath | 3,736 |

| Nethercross | An Chrois Íochtarach | 22,616 |

| Newcastle | An Caisleán Nua | 21,238 |

| Rathdown | Ráth an Dúin | 29,974 |

| Uppercross | An Chrois Uachtarach | 39,032 |

Townlands

Townlands are the smallest officially defined geographical divisions in Ireland. There are 1,090 townlands in Dublin, of which 88 are historic town boundaries. These town boundaries are registered as their own townlands and are much larger than rural townlands. The smallest rural townlands in Dublin are just 1 acre in size, most of which are offshore islands (Clare Rock Island, Lamb Island, Maiden Rock, Muglins, Thulla Island). The largest rural townland in Dublin is 2,797 acres (Caastlekelly). The average size of a townland in the county (excluding towns) is 205 acres.

Towns and suburbs

Urban and rural districts

Under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, County Dublin was divided into urban districts of Blackrock, Clontarf, Dalkey, Drumcondra, Clonliffe and Glasnevin, Killiney and Ballybrack, Kingstown, New Kilmainham, Pembroke, and Rathmines and Rathgar, and the rural districts of Balrothery, Celbridge No. 2, North Dublin, Rathdown, and South Dublin.[45]

Howth, formerly within the rural district of Dublin North, became an urban district in 1919.[46] Kingstown was renamed Dún Laoghaire in 1920.[47] The rural districts were abolished in 1930.[48]

Balbriggan, in the rural district of Balrothery, had town commissioners under the Towns Improvement (Ireland) Act 1854. This became a town council in 2002.[49] In common with all town councils, it was abolished in 2014.

The urban districts were gradually absorbed by the city of Dublin, except for four coastal districts of Blackrock, Dalkey, Dún Laoghaire, and Killiney and Ballybrack, which formed the borough of Dún Laoghaire in 1930.[50]

County boundaries

| Year | Changes |

|---|---|

| 1900 | Abolition of the urban districts of Clontarf, Drumcondra, Clonliffe and Glasnevin and New Kilmainham and transfer with the surrounding areas to the city[51] |

| 1930 | Abolition of the urban districts of Pembroke and Rathmines and Rathgar, and transfer to the city[52] |

| 1931 | Transfer of Drumcondra, Glasnevin, Donnybrook and Terenure to the city[53] |

| 1941 | Transfer of Crumlin to the city[54] |

| 1942 | Abolition of the urban district of Howth, and transfer to the city[55] |

| 1953 | Transfer of Finglas, Coolock and Ballyfermot to the city[56] |

| 1985 | Transfer of Santry and Phoenix Park to the city transfer of Howth, Sutton and parts of Kilbarrack including Bayside from the city[57] |

| 1994 | Abolition of County Dublin and the borough of Dún Laoghaire on the establishment of new counties |

Counties and the city

The city of Dublin had been administered separately since the 13th century. Under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, the two areas were defined as the administrative county of Dublin and the county borough of Dublin, with the latter in the city area.

In 1985, County Dublin was divided into three electoral counties: Dublin–Belgard to the southwest (South Dublin from 1991), Dublin–Fingal to the north (Fingal from 1991), and Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown to the southeast.[58][59][60]

On 1 January 1994, under the Local Government (Dublin) Act 1993, the County Dublin ceased to exist as a local government area, and was succeeded by the counties of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal and South Dublin, each coterminous (with minor boundary adjustments) with the area of the corresponding electoral county.[61][62] In discussing the legislation, Avril Doyle TD said, "The Bill before us today effectively abolishes County Dublin, and as one born and bred in these parts of Ireland I find it rather strange that we in this House are abolishing County Dublin. I am not sure whether Dubliners realise that that is what we are about today, but in effect that is the case."[63]

Although the Electoral Commission should, as far as practicable, avoid breaching county boundaries when recommending Dáil constituencies, this does not include the boundaries of a city or the boundary between the three counties in Dublin.[64] There is also still a sheriff appointed for County Dublin.[65]

The term "County Dublin" is still in common usage. Many organisations and sporting teams continue to organise on a County Dublin basis. The Placenames Branch of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media maintains a Placenames Database that records all placenames, past and present.[66] County Dublin is listed in the database along with the subdivisions of that county.[67][68] It is also used as an address for areas within Dublin outside of the Dublin postal district system.[69][70]

For a period in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, to reduce person-to-person contact, government regulations restricted activity to "within the county in which the relevant residence is situated". Within the regulations, the local government areas of "Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal, South Dublin and Dublin City" were deemed to be a single county (as were the city and the county of Cork, and the city and the county of Galway).[71]

The latest Ordnance Survey Ireland "Discovery Series" (Third Edition 2005) 1:50,000 map of the Dublin Region, Sheet 50, shows the boundaries of the city and three surrounding counties of the region. Extremities of the Dublin Region, in the north and south of the region, appear in other sheets of the series, 43 and 56 respectively.

Local government

There are four local authorities whose remit collectively encompasses the geographic area of the county and city of Dublin. These are Dublin City Council, South Dublin County Council, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council and Fingal County Council.

Until 1 January 1994, the administrative county of Dublin was administered by Dublin County Council. From that date, its functions were succeeded by Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council, Fingal County Council and South Dublin County Council, each with its county seat, respectively administering the new counties established on that date.[72]

The city was previously designated a county borough and administered by Dublin Corporation. Under the Local Government Act 2001, the country was divided into local government areas of cities and counties, with the county borough of Dublin being designated a city for all purposes, now administered by Dublin City Council. Each local authority is responsible for certain local services such as sanitation, planning and development, libraries, the collection of motor taxation, local roads and social housing.

Dublin, comprising the four local government areas in the county, is a strategic planning area within the Eastern and Midland Regional Assembly (EMRA).[73][74] It is a NUTS Level III region of Ireland. The region is one of eight regions of Ireland for Eurostat statistics at NUTS 3 level.[75] Its NUTS code is IE061.

This area formerly came under the remit of the Dublin Regional Authority.[76] This Authority was dissolved in 2014.[77]

| Dublin City | Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown | Fingal | South Dublin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coat of Arms |  |

|

|

|

| Motto | Latin: Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas "An Obedient Citizenry Produces a Happy City" |

Irish: Ó Chuan go Sliabh "From Harbour to Mountain" |

Irish: Flúirse Talaimh is Mara "Abundance of Land and Sea" |

Irish: Ag Seo Ár gCúram "This We Hold in Trust" |

| County town | Dublin | Dún Laoghaire | Swords | Tallaght |

| Dáil constituencies | Dublin Central Dublin Bay North Dublin Bay South Dublin North-West Dublin South-Central Dublin West |

Dún Laoghaire Dublin Rathdown |

Dublin Bay North Dublin Fingal Dublin North-West Dublin West |

Dublin Mid-West Dublin South-Central Dublin South-West |

| Local authority | Dublin City Council | Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown County Council |

Fingal County Council | South Dublin County Council |

| Council Seats | 63 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Chairperson | Daithí de Róiste (Lord Mayor) |

Denis O'Callaghan (Cathaoirleach) |

Adrian Henchy (Mayor) |

Alan Edge (Mayor) |

| EMRA Seats | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Population (2022) | 592,713 | 233,860 | 330,506 | 301,705 |

| Increase since 2016 | ||||

| Area | 118 km2 (46 sq mi)[78] | 126 km2 (49 sq mi)[79] | 456 km2 (176 sq mi)[80] | 223 km2 (86 sq mi)[81] |

| Density | 5,032/km2 | 1,859/km2 | 725/km2 | 1,355/km2 |

| Highest elevation | N/A | Two Rock 536 m (1,759 ft) |

Knockbrack 176 m (577 ft) |

Kippure 757 m (2,484 ft) |

| Website | dublincity |

dlrcoco |

fingal |

sdcc |

Demographics

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 14,755 | — |

| 1510 | 23,471 | +59.1% |

| 1550 | 21,678 | −7.6% |

| 1580 | 20,345 | −6.1% |

| 1585 | 20,224 | −0.6% |

| 1600 | 24,556 | +21.4% |

| 1610 | 12,567 | −48.8% |

| 1653 | 18,847 | +50.0% |

| 1659 | 21,827 | +15.8% |

| 1672 | 55,678 | +155.1% |

| 1680 | 101,414 | +82.1% |

| 1690 | 145,219 | +43.2% |

| 1700 | 161,234 | +11.0% |

| 1710 | 173,690 | +7.7% |

| 1720 | 205,111 | +18.1% |

| 1725 | 212,670 | +3.7% |

| 1735 | 209,785 | −1.4% |

| 1745 | 217,666 | +3.8% |

| 1755 | 235,799 | +8.3% |

| 1765 | 244,103 | +3.5% |

| 1771 | 255,297 | +4.6% |

| 1775 | 271,475 | +6.3% |

| 1781 | 285,799 | +5.3% |

| 1788 | 291,433 | +2.0% |

| 1790 | 297,644 | +2.1% |

| 1801 | 300,345 | +0.9% |

| 1811 | 305,766 | +1.8% |

| 1813 | 311,798 | +2.0% |

| 1816 | 318,760 | +2.2% |

| 1821 | 335,892 | +5.4% |

| 1831 | 380,167 | +13.2% |

| 1841 | 372,773 | −1.9% |

| 1851 | 405,147 | +8.7% |

| 1861 | 410,252 | +1.3% |

| 1871 | 405,262 | −1.2% |

| 1881 | 418,910 | +3.4% |

| 1891 | 419,216 | +0.1% |

| 1901 | 448,206 | +6.9% |

| 1911 | 477,196 | +6.5% |

| 1926 | 505,654 | +6.0% |

| 1936 | 586,925 | +16.1% |

| 1946 | 636,193 | +8.4% |

| 1951 | 693,022 | +8.9% |

| 1956 | 705,781 | +1.8% |

| 1961 | 718,332 | +1.8% |

| 1966 | 795,047 | +10.7% |

| 1971 | 852,219 | +7.2% |

| 1979 | 983,683 | +15.4% |

| 1981 | 1,003,164 | +2.0% |

| 1986 | 1,021,449 | +1.8% |

| 1991 | 1,025,304 | +0.4% |

| 1996 | 1,058,264 | +3.2% |

| 2002 | 1,122,821 | +6.1% |

| 2006 | 1,187,176 | +5.7% |

| 2011 | 1,270,603 | +7.0% |

| 2016 | 1,345,402 | +5.9% |

| 2022 | 1,458,154 | +8.4% |

| [82][83][84][85][86][87] | ||

.jpeg.webp)

As of the 2022 census, the population of Dublin was 1,458,154, an 8.4% increase since the 2016 Census. The county's population first surpassed 1 million in 1981, and is projected to reach 1.8 million by 2036.[88]

Dublin is Ireland's most populous county, a position it has held since the 1926 Census, when it overtook County Antrim. As of 2022, County Dublin has over twice the population of County Antrim and two and a half times the population of County Cork. Approximately 21% of Ireland's population lives within County Dublin (28% if only the Republic of Ireland is counted). Additionally, Dublin has more people than the combined populations of Ireland's 16 smallest counties.

With an area of just 922 km2 (356 sq mi), Dublin is by far the most densely populated county in Ireland. The population density of the county is 1,582 people per square kilometre – over 7 times higher than Ireland's second most densely populated county, County Down in Northern Ireland.

During the Celtic Tiger period, a large number of Dublin natives (Dubliners) moved to the rapidly expanding commuter towns in the adjoining counties. As of 2022, approximately 27.2% (345,446) of Dubliners were living outside of County Dublin. People born within Dublin account for 28% of the population of Meath, 32% of Kildare, and 37% of Wicklow. There are 922,744 Dublin natives living within the county, accounting for 63.3% of the population. People born in other Irish counties living within Dublin account for roughly 11% of the population.[89]

Between 2016 and 2022, international migration produced a net increase of 88,300 people. Dublin has the highest proportion of international residents of any county in Ireland, with around 25% of the county's population being born outside of the Republic of Ireland.[90]

As of the 2022 census, 5.6 percent of the county's population was reported as younger than 5 years old, 25.7 percent were between 5 and 25, 55.3 percent were between 25 and 65, and 13.4 percent of the population was older than 65. Of this latter group, 48,865 people (3.4 percent) were over the age of 80, more than doubling since 2016. Across all age groups, there were slightly more females (51.06 percent) than males (48.94 percent).[91]

In 2021, there were 16,596 births within the county, and the average age of a first time mother was 31.9.[92]

Migration

Over a quarter (25.2 percent) of County Dublin's population was born outside of the Republic of Ireland. In 2022, Dublin City had the highest percentage of non-nationals in the county (27.3 percent), and South Dublin had the lowest (20.9 percent).[93] Historically, the immigrant population of Dublin was mainly from the United Kingdom and other European Union member states. However, results from the 2022 census revealed that immigrants from non-EU/UK countries were the largest source of foreign-born residents for the first time, accounting for 12.9 percent of the county's population. Those from other European Union member states accounted for 8.3 percent of Dublin's population, and those from the United Kingdom a further 4.1 percent.[94]

Prior to the 2000s, the UK was consistently the largest single source of non-nationals living in Dublin. After declining in the previous two census periods, the number of UK-born residents living in Dublin increased by 5.8 percent between 2016 and 2022. There was a large difference between the number of people living in Dublin who were born in the UK (58,586) and those who held sole-UK citizenship in the 2022 census (22,936). This discrepancy can arise for a variety of factors, such as people born in Northern Ireland claiming Irish citizenship rather than UK citizenship, Irish people born in the UK who now live in Dublin, British people who have become natural citizens, and foreign residents of Dublin who were born in the UK but are not UK citizens. Depending on an individual's responses in the census, all of these examples could result in the country of birth being registered by the CSO as the United Kingdom, but nationality being registered as Irish or a third country.

Following its accession to the EU, the Polish quickly became the fastest growing immigrant community in Dublin. Just 188 Poles applied for Irish work permits in 1999. By 2006 this number had grown to 93,787.[95] After the 2008 Irish economic downturn, as many as 3,000 Poles left Ireland each month. Despite this, Poles remain one of Dublin's largest foreign-born groups. In contrast to more recent arrivals, a large percentage of Dublin's Polish citizens (30.9 percent) also hold Irish citizenship.

| Country | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizenship (Country only) |

24,755 | 22,936 | 17,062 | 23,730 | 15,631 | 5,912 | 10,947 | 10,016 | 7,245 | 8,196 |

| Citizenship (Dual Irish-Country) |

3,485 | 4,803 | 7,627 | 210 | 810 | 7,926 | 962 | 945 | 1,216 | 234 |

| Combined Population (2022) | 28,240 | 27,739 | 24,689 | 23,940 | 16,441 | 13,838 | 11,909 | 10,961 | 8,461 | 8,430 |

Outside of Europe, Indians and Brazilians are the predominant foreign-national groups. As of 2022, Indians were the fastest growing major immigrant group in Dublin, and they are now the county's second largest foreign-born group after the UK. Dublin's Indian community grew by 155.2 percent between 2016 and 2022. There were 29,582 Indian-born residents within Dublin as of 2022, up from 9,884 in the 2011 census.[97] The influx of Indians is driven in part by multinational tech companies such as Microsoft, Google and Meta who have located their European headquarters within the county, in areas such as the Silicon Docks and Sandyford. In August 2020, the first dedicated Hindu temple in Ireland was built in Walkinstown.[98]

The number of Brazilian citizens living in Dublin more than tripled between 2011 and 2022, from 4,641 to 16,441. This increase is mainly a result of Ireland's participation in the Brazilian government's Ciência sem Fronteiras programme, which sees thousands of Brazilian students come to study in Ireland each year, many of whom remain in the country afterwards.[99]

Although not fully captured during the census period, Dublin also houses a significant number of Ukrainian refugees under the Temporary Protection Directive. As of October 2023, the number of Ukrainians living in emergency accommodation within the county is estimated to be around 14,000.[100]

Ethnicity

According to the Central Statistics Office, in 2022 the population of County Dublin self-identified as:

- 80.4% White (68.0% White Irish, 12.0% Other White Background, 0.4% Irish Traveller)

- 5.8% Asian

- 3.0% Mixed background

- 2.2% Black

- 8.5% Not Stated

By ethnicity, in 2022 the population was 80.4% white. Those who identified as White Irish constituted 68.0% of the county's population, and Irish Travellers accounted for a further 0.4%. Caucasians who did not identify as ethnically Irish accounted for 12.0% of the population.

In terms of total numbers, Dublin has the largest non-white population in Ireland, with an estimated 158,653 residents, accounting for 11.1% of the county's population. Over two-fifths (42.2 percent) of Ireland's black residents live within the county. In terms of percentage of population, Fingal has the highest percentage of both black (3.6 percent) and non-white (12.4 percent) residents of any local authority in Ireland. Conversely, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown in the south of the county has one of Ireland's lowest percentages of black residents, with only 0.77% of the population identifying as black in 2022. Additionally, 43.3% of Ireland's multiracial population lives within County Dublin. Those who did not state their ethnicity more than doubled between 2016 and 2022, from 4.1% to 8.5%.[101]

Religion

.jpg.webp)

The largest religious denomination by both number of adherents and as a percentage of Dublin's population in 2022 was the Roman Catholic Church, at 57.4 percent. All other Christian denominations including Church of Ireland, Eastern Orthodox, Presbyterian and Methodist accounted for 8.1 percent of Dublin's population. Together, all denominations of Christianity accounted for 65.5 percent of the county's population. According to the 2022 census, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown is the least religious local authority in Ireland, with 23.9 percent of the population declaring themselves non-religious, followed closely by Dublin city (22.6 percent). In the county as a whole, those unaffiliated with any religion represented 20.1 percent of the population, which is the largest percentage of non-religious people of any county in Ireland. A further 9.1 percent of the population did not state their religion, up from just 4.1 percent in 2016.

Of the non-Christian religions, Islam is the largest in terms of number of adherents, with Muslims accounting for 2.6% of the population. After Islam, the largest non-Christian religions in 2022 were Hinduism (1.4 percent) and Buddhism (0.27 percent). While relatively small in absolute terms, County Dublin contains over half of Ireland's Hindu (58.7 percent) residents, and just under half of its Eastern Orthodox (45.3 percent), Islamic (45.0 percent) and Buddhist (41.7 percent) residents.[102]

Dublin and its hinterland has been a Christian diocese since 1028. For centuries, the Primacy of Ireland was disputed between Dublin, the social and political capital of Ireland, and Armagh, site of Saint Patrick's main church, which was founded in 445 AD. In 1353 the dispute was settled by Pope Innocent VI, who proclaimed that the Archbishop of Dublin was Primate of Ireland, while the Archbishop of Armagh was titled Primate of All Ireland. These two distinct titles were replicated in the Church of Ireland following the Reformation. Historically, County Dublin was the epicentre of Protestantism in Ireland outside of Ulster. Records from the 1891 census show that the county was 21.4 percent Protestant towards the end of the 19th century. By the 1911 census this had gradually declined to around 20% due to poor economic conditions, as Dublin Protestants moved to industrial Belfast. Following the War of Independence (1919–1921), Dublin's Protestant community went into a steady decline, falling to 8.5 percent of the population by 1936.[103]

Between 2016 and 2022, the fastest growing religions in Dublin were Hinduism (148.9 percent), Eastern Orthodox (51.6 percent), and Islam (27.9 percent), while the most rapidly declining religions were Evangelicalism (-10.4 percent), Catholicism (−8.7 percent), Jehovah's Witnesses (−5.9 percent) and Buddhism (−5.4 percent).

Metropolitan Area

Dublin city

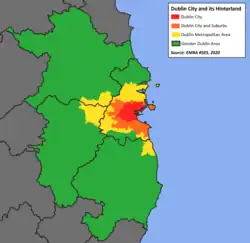

The boundaries of Dublin City Council form the urban core of the city, often referred to as "Dublin city centre", an area of 117.8 square kilometres. This encompasses the central suburbs of the city, extending as far south as Terenure and Donnybrook; as far north as Ballymun and Donaghmede; and as far west as Ballyfermot. As of 2022, there were 592,713 people living within Dublin city centre. However, as the continuous built-up area extends beyond the city boundaries, the term "Dublin city and suburbs" is commonly employed when referring to the actual extent of Dublin.

Dublin city and suburbs

Dublin city and suburbs is a CSO-designated urban area which includes the densely populated contiguous built-up area which surrounds Dublin city centre. It encompasses 317.5 km2 and contains approximately 87% of County Dublin's population (1,263,219 people) as of the 2022 census.[104]

Dublin Metropolitan Area

As the city proper does not extend beyond Dublin Airport, the towns of "North County Dublin" such as Swords, Lusk, Rush and Malahide are not considered part of the city, and are recorded by the CSO as separate settlements. Under Ireland's National Planning Framework, these towns are considered part of the Dublin Metropolitan Area (DMA). The DMA also includes towns outside of the county, such as Naas, Leixlip and Maynooth in County Kildare, and Bray and Greystones in County Wicklow, but does not include Balbriggan or Skerries, which are located in the far north of County Dublin.[105]

Greater Dublin Area

The Greater Dublin Area (GDA) is a commonly used planning jurisdiction which extends to the wider network of commuter towns that are economically connected to Dublin city. The GDA consists of County Dublin and its three neighboring counties, Kildare, Meath and Wicklow.[106]

With a population of 2.1 million and an area of 6,986 square kilometres, it contains 40% of the population of the State, and covers 9.9% of its land area.

| Statistical Area | Population (2022) | Area (km2) | Density (per km2) | Local Authorities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dublin City | 592,713 | 117.8 | 5,032 | Dublin |

| Dublin City and suburbs | 1,263,219 | 317.5 | 3,979 | Dublin, Fingal, South Dublin, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown |

| County Dublin | 1,458,154 | 922 | 1,582 | Dublin, Fingal, South Dublin, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown |

| Dublin Metropolitan Area | 1,417,700 | 1,000 | 1,418 | Dublin, Fingal, South Dublin, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Meath, Kildare, Wicklow |

| Greater Dublin Area | 2,082,605 | 6,986 | 298 | Dublin, Fingal, South Dublin, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Meath, Kildare, Wicklow |

Urban Areas

Under CSO classification, an "Urban Area" is a town with a population greater than 1,500. Dublin is the most urbanised county in Ireland, with 98% of its residents residing in urban areas as of 2022. Of Dublin's three non-city local authorities, Fingal has the highest proportion of people living in rural areas (7.9%), while Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown has the lowest (1.19%). The western suburbs of Dublin city such as Tallaght and Blanchardstown have experienced rapid growth in recent decades, and both areas have a population roughly equivalent to Galway city.

| Rank | Local Authority | Pop. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpeg.webp) Dublin  Tallaght |

1 | Dublin | Dublin City | 592,713 | _-_20170819143036.jpg.webp) Blanchardstown  Lucan | ||||

| 2 | Tallaght | South Dublin | 81,022 | ||||||

| 3 | Blanchardstown | Fingal | 79,769 | ||||||

| 4 | Lucan | South Dublin, Fingal | 57,550 | ||||||

| 5 | Clondalkin | South Dublin | 47,938 | ||||||

| 6 | Swords | Fingal | 40,776 | ||||||

| 7 | Dún Laoghaire | Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown | 31,239 | ||||||

| 8 | Castleknock | Fingal | 27,332 | ||||||

| 9 | Dundrum | Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown | 25,414 | ||||||

| 10 | Balbriggan | Fingal | 24,322 | ||||||

Transportation

.png.webp)

County Dublin has the oldest and most extensive transportation infrastructure in Ireland. The Dublin and Kingstown Railway, opened in December 1834, was Ireland's first railway line. The line, which ran from Westland Row to Dún Laoghaire, was originally intended to be used for cargo. However, it proved far more popular with passengers and became the world's first commuter railway line.[109] The line has been upgraded multiple times throughout its history and is still in use to this day, making it the oldest commuter railway route in the world.

Public transport in Dublin was managed by the Dublin Transportation Office until 2009, when it was replaced by the National Transport Authority (NTA). The three pillars currently underpinning the public transport network of the Greater Dublin Area (GDA) are Dublin Suburban Rail, the Luas and the bus system. There are six commuter lines in Dublin, which are managed by Iarnród Éireann. Five of these lines serve as routes between Dublin and towns across the GDA and beyond. The sixth route, known as Dublin Area Rapid Transit (DART), is electrified and serves only Dublin and northern Wicklow. The newest addition to Dublin's public transport network is a tram system called the Luas. The service began with two disconnected lines in 2004,[110] with three extensions opened in 2009,[111] 2010[112] and 2011[113] before a cross-city link between the lines and further extension opened in 2017.[114]

Historically, Dublin had an extensive tram system which commenced in 1871 and at its peak had over 97 km (60 mi) of active line. It was operated by the Dublin United Transport Company (DUTC) and was very advanced for its day, with near-full electrification from 1901. From the 1920s onwards, the DUTC began to acquire private bus operators and gradually closed some of its lines. Further declines in passenger numbers were driven in part by a belief at the time that trams were outdated and archaic. All tram lines terminated in 1949, except for the tram to Howth, which ran until 1959.

Dublin Bus is the county's largest bus operator, carrying 138 million passengers in 2019.[115] For much of the city, particularly west Dublin, the bus is the only public transport option available, and there are numerous smaller private bus companies in operation across County Dublin. National bus operator Bus Éireann provides long-distance routes to towns and villages located outside of Dublin city and its immediate hinterland.

In November 2005, the government announced a €34 billion initiative called Transport 21 which included a substantial expansion to Dublin's transport network. The project was cancelled in May 2011 in the aftermath of the 2008 recession. Consequently, by 2017 Hugh Creegan, deputy chief of the NTA, stated that there had been a "chronic underinvestment in public transport for more than a decade".[116] By 2019, Dublin was reportedly the 17th most congested city in the world, and had the 5th highest average commute time in the European Union.[117][118] The Luas and rail network regularly experience significant overcrowding and delays during peak hours, and in 2019 Iarnród Éireann was widely ridiculed for asking commuters to "stagger morning journeys" to alleviate the problem.[119]

The M50 is a 45.5 km (28.3 mi) orbital motorway around Dublin city, and is the busiest motorway in the country. It serves as the centre of both Dublin and Ireland's motorway network, and most of the national primary roads to other cities begin at the M50 and radiate outwards. The current route was built in various sections over the course of 27 years, from 1983 to 2010. All major roads in Ireland are managed by Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII), which is headquartered in Parkgate Street, Dublin 8. As of 2019, there were over 550,000 cars registered in County Dublin, accounting for 25.3% of all cars registered in the State.[120] Due to the county's small area and high degree of urbanisation, there is a preference for "D" registered used cars throughout Ireland, as they are considered to have undergone less wear and tear.[121]

For international travel, around 1.7 million passengers travel by ferry through Dublin Port each year.[122] A Dún Laoghaire to Holyhead ferry was formerly operated by Stena Line, but the route was closed in 2015. Dublin Airport is Ireland's largest airport, and 32.9 million passengers passed through it in 2019, making it Europe's 12th-busiest airport.[123]

Economy

.png.webp)

The Dublin Region, which is conterminous with County Dublin, has the largest and most highly developed economy in Ireland, accounting for over two-fifths of national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The Central Statistics Office estimates that the GDP of the Dublin Region in 2020 was €157.2 billion ($187 billion / £141 billion at 2020 exchange rates).[124] In nominal terms, Dublin's economy is larger than roughly 140 sovereign states. The county's GDP per capita is €107,808 ($117,688 / £92,620), one of the highest regional GDPs per capita in the EU. As of 2019, Dublin also had the highest Human Development Index in Ireland at 0.965, placing it among the most developed places in the world in terms of life expectancy, education and per capita income.[125]

Affluence

In 2020, average disposable income per person in Dublin was €27,686, or 118% of the national average (€23,400), the highest of any county in Ireland.[126] As Ireland's most populous county, Dublin has the highest total household income in the country, at an estimated €46.8 billion in 2017 – higher than the Border, Midlands, West and South-East regions combined. Dublin residents were the highest per capita tax contributors in the State, returning a total of €15.1 billion in taxes in 2017.[127]

Many of Ireland's most prominent political, educational, cultural and media centres are concentrated south of the River Liffey in Dublin city. Further south, areas like Dún Laoghaire, Dalkey and Killiney have long been some of Dublin's most affluent areas, and Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown consistently has the highest average house prices in Ireland. This has resulted in a perceived socio-economic divide in Dublin, between the generally less affluent Northside and the wealthier Southside. In Dublin (both city and county), residents will commonly refer to themselves as a "Northsider" or a "Southsider", and the division is often caricatured in Irish comedy, media and literature, for example Ross O'Carroll-Kelly and Damo and Ivor.[128] References to the divide have also become colloquialisms in their own right, such as "D4" (referring to the Dublin 4 postal district), which is a pejorative term for an upper middle class Irish person.[129]

While the northside-southside divide remains prevalent in popular culture, economic indices such as the Pobal HP deprivation index have shown that the distinction does not reflect economic reality. Many of Dublin's most affluent areas (Clontarf, Raheny, Howth, Portmarnock, Malahide) are located in the north of the county, and many of its most deprived areas (Jobstown, Ballyogan, Ballybrack, Dolphin's Barn, Clondalkin) are located in the south of the county.

Utilising CSO data from the past three censuses, Pobal HP revealed that there was a much higher concentration of below average, disadvantaged and very disadvantaged areas in west Dublin.[130] In 2012, Irish Times columnist Fintan O'Toole posited that the real economic divide in Dublin was not north–south, but east–west – between the older coastal areas of eastern Dublin and the newer sprawling suburbs of western Dublin – and that the perpetuation of the northside–southside "myth" was a convenient way to gloss over class division within the county. O'Toole argued that framing the city's wealth divide as a light-hearted north–south stereotype was easier than having to address the socio-economic impacts of deliberate government policy to remove working-class people from the city centre and settle them on the margins.[131]

Finance

Dublin is both a European and Global financial hub, and around 200 of the world's leading financial services firms have operations within the county. In 2017 and 2018 respectively, Dublin was ranked 5th in Europe and 31st globally in the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI).[132][133] In the mid-1980s, parts of central Dublin had fallen into a state of dereliction and the Irish government pursued an urban regeneration programme. An 11-hectare special economic zone (SEZ) was set up in 1987, known as the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC). At the time of its establishment, the SEZ had the lowest corporate tax rate in the EU. The IFSC has since expanded into a 37.8-hectare site centred around the Dublin Docklands. As of 2020, over €1.8 trillion of funds are administered from Ireland.[134]

There was renewed interest in Dublin's financial services sector in the wake of the UK's vote to withdraw from the European Union in 2016. Many firms, including Barclays and Bank of America, pre-emptively moved some of their operations from London to Dublin in anticipation of restricted EU market access.[135] A survey conducted by Ernst & Young in 2021 found that Dublin was the most popular destination for firms in the UK considering relocating to the EU, ahead of Luxembourg and Frankfurt.[136] It is estimated that Dublin's financial sector will grow by about 25% as a direct result of Brexit, and as many as 13,000 jobs could move from the UK to County Dublin in the years immediately after its withdrawal.[137]

Industry and Energy

_(32979900775).jpg.webp)

The economy of Dublin benefits from substantial amounts of both indigenous and foreign investment. In 2018, the Financial Times ranked Dublin the most attractive large city in the world for Foreign Direct Investment, and the city has been consistently ranked by Forbes as one of the world's most business-friendly.[138][139] The economy is centered on financial services, the pharmaceuticals and biotechnology industries, information technology, logistics and storage, professional services, agriculture and tourism. IDA Ireland, the state agency responsible for attracting foreign direct investment, was founded in Dublin in 1949.

Dublin has four power plants, all of which are concentrated in the docklands area of Dublin city. Three are natural-gas plants operated by the ESB, and the Poolbeg Incinerator is operated by Covanta Energy. The four plants have a combined capacity of 1.039 GW, roughly 12.5% of the island of Ireland's generation capacity as of 2019.[140] The disused Poolbeg chimneys are the tallest structures in the county, and were granted protection by Dublin city council in 2014.[141]

As a result of Dublin city's location within a sheltered bay at the mouth of a navigable river, shipping has been a key industry in the county since medieval times. By the 18th-century, Dublin was a bustling maritime city and large-scale engineering projects were undertaken to enhance the port's capacity, such as the Great South Wall, which was the largest sea wall in the world at the time of its construction in 1715.[142] Dublin Port was originally located along the Liffey, but gradually moved towards the coast over the centuries as vessel size increased. It is today the largest and busiest port in Ireland. It handles 50% of the Republic of Ireland's trade, and receives 60% of all vessel arrivals.[143]

Dublin Port occupies an area of 259 hectares (640 acres) in one of the most expensive places in the country, with an estimated price per acre of around €10 million. Since the 2000s, there have been calls to relocate Dublin Port out of the city and free up its land for residential and commercial development. This was first proposed by the Progressive Democrats at the height of the Celtic Tiger in 2006, who valued the land at between €25 and €30 billion, although nothing became of this proposal. During the housing crisis of the late 2010s the idea again began to attract supporters, among them economist David McWilliams.[144] Currently, there are no official plans to move the port elsewhere, and the Dublin Port Company strongly opposes relocation.[145]

Dublin hosts the headquarters of some of Ireland's largest multinational corporations, including 14 of the 20 companies which make up the ISEQ 20 index – those with the highest trading volume and market capitalisation of all Irish Stock Exchange listed companies. These are: AIB, Applegreen, Bank of Ireland, Cairn Homes, Continental Group, CRH, Dalata Hotel Group, Flutter Entertainment, Greencoat Renewables, Hibernia REIT, IRES, Origin Enterprises, Ryanair and Smurfit Kappa.

Tourism

County Dublin receives by far the most overseas tourists of any county in Ireland. This is primarily due to Dublin city's status as Ireland's largest city and its transportation hub. Dublin is also Ireland's most popular destination for domestic tourists. According to Fáilte Ireland, in 2017 Dublin received nearly 6 million overseas tourists, and just under 1.5 million domestic tourists. Most of Ireland's international flights transit through Dublin Airport, and the vast majority of passenger ferry arrivals dock at Dublin Port. In 2019, the port also facilitated 158 cruise ship arrivals.[146] The tourism industry in the county is worth approximately €2.3 billion per year.[147]

As of 2019, 4 of the top 10 fee-paying tourist attractions in Ireland are located within County Dublin, as well as 5 of the top 10 free attractions. The Guinness Storehouse at St. James's Gate is Ireland's most visited tourist attraction, receiving 1.7 million visitors in 2019, and over 20 million total visits since 2000. Additionally, Dublin also contains Ireland's 3rd (Dublin Zoo), 4th (Book of Kells) and 6th (St Patrick's Cathedral) most visited fee-paying attractions. The top free attractions in Dublin are the National Gallery of Ireland, the National Botanic Gardens, the National Museum of Ireland and the Irish Museum of Modern Art, all of which receive over half a million visitors per year.[148]

Agriculture

.jpg.webp)

Despite having the smallest farmed area of any county, Dublin is one of Ireland's major agricultural producers. Dublin is the largest producer of fruit and vegetables in Ireland, the third largest producer of oilseed rape and has the fifth largest fishing industry. Fingal alone produces 55% of Ireland's fresh produce, including soft fruits and berries, apples, lettuces, peppers, asparagus, potatoes, onions, and carrots. As of 2020, the Irish Farmers' Association estimates that the total value of Dublin's agricultural produce is €205 million.[149] According to the CSO, fish landings in the county are worth a further €20 million.[150]

Approximately 41% of the county's land area (38,576 ha) is farmed. Of this, 12,578 ha (31,081 acres) is under tillage, the 9th highest in the country, and 6,500 ha (16,062 acres) is dedicated to fruit & horticulture, the 4th highest. Rural County Dublin is considered a peri-urban region, where an urban environment transitions into a rural one. Due to the growth of Dublin city and its commuter towns in the north of the county, the region is considered to be under significant pressure from urban sprawl. Between 1991 and 2010, the amount of agricultural land within the county decreased by 22.9%. In 2015, the local authorities of Fingal, South Dublin and Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown developed a joint Dublin Rural Local Development Strategy aimed at enhancing the region's agricultural output, while also managing and minimising the impact of urbanisation on biodiversity and the identity and culture of rural Dublin.[151]

The county has a small forestry industry that is based almost entirely in the upland areas of south County Dublin. According to the 2017 National Forestry Inventory, 6,011 ha (14,854 acres) of the county was under forest, of which 1,912 ha (4,725 acres) was private forestry.[152] The majority of Dublin's forests are owned by the national forestry company, Coillte. In the absence of increased private planting, the county's commercial timber capacity is expected to decrease in the coming decades, as Coillte intends to convert much of their holdings in the Dublin Mountains into non-commercial mixed forests.[153]

Dublin has 810 individual farms with an average size of 47.6 ha (118 acres), the largest average farm size of any county in Ireland. Roughly 9,400 people within the county are directly employed in either agriculture or the food and drink processing industry. Numerous Irish and multinational food and drink companies are either based in Dublin or have facilities within the county, including Mondelez, Coca-Cola, Mars, Diageo, Kellogg's, Danone, Ornua, Pernod Ricard and Glanbia. In 1954, Tayto Crisps were established in Coolock and developed into cultural phenomenon throughout much of the Republic of Ireland.[154] Its operations and headquarters have since moved to neighbouring County Meath. Another popular crisp brand, Keogh's, are based in Oldtown, Fingal.[155]

Education

In Ireland, spending on education is controlled by the government and the allocation of funds is decided each year in the annual budget. Local authorities retain limited responsibilities such as funding for school meals, service supports costs and the upkeep of libraries.

There are hundreds of primary and secondary schools within County Dublin, most of which are English-language schools. Several international schools are based in Dublin, such as St Kilian's German School and Lycée Français d'Irlande, which teach in foreign languages. There is also a large minority of students attending gaelscoileanna (Irish-language primary schools). There are 34 gaelscoileanna and 10 gaelcholáistí (Irish-language secondary schools) in the county, with a total of 12,950 students as of 2018.[156] In terms of college acceptance rates, gaelcholáistí are consistently the best performing schools in Dublin, and among the best performing in Ireland.[157]

Although the government pays for a large majority of school costs, including teachers' salaries, the Roman Catholic Church is the largest owner of schools in Dublin, and preference is given to Catholic students over non-Catholic students in oversubscribed areas.[158] This has resulted in a growing movement towards non-denominational and co-educational schools in the county.[159]

The majority of private secondary schools in Dublin are still single sex, and continue to have religious patronages with either congregations of the Catholic Church (Spiritans, Sisters of Loreto, Jesuits) or Protestant denominations (Church of Ireland, Presbyterian). Newer private schools which cater for the Leaving Cert cycle such as the Institute of Education and Ashfield College are generally non-denominational and co-educational. In 2018, Nord Anglia International School Dublin opened in Leopardstown, becoming the most expensive private school in Ireland.[160]

As of 2023–24, four of Dublin's third level institutions are listed in the Top 500 of either the Times Higher Education Rankings or the QS World Rankings, placing them amongst the top 5% of all third level institutions in the world. TCD (81), UCD (171) and DCU (436) are within the Top 500 of the QS rankings; and TCD (161), RCSI (201–250), UCD (201–250) and DCU (451-500) and are within the Top 500 of the Times rankings. Newly amalgamated TUD also placed within the world's Top 1,000 universities in the QS rankings, and within the Top 500 for Engineering and Electronics.[161][162]

County Dublin has four public universities, as well as numerous other colleges, institutes of technology and institutes of further education. Several of Dublin's largest third level institutions and their associated abbreviations are listed below:

_p049_THE_COLLEGE_OF_SURGEONS.jpg.webp)

- Dublin Business School (DBS)

- Dublin City University (DCU)

- Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT)

- Griffith College Dublin (GCD)

- National College of Ireland (NCI)

- Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI)

- Technological University Dublin (TUD)

- Trinity College Dublin (TCD)

- University College Dublin (UCD)

Politics

Elections

.png.webp)

For elections to Dáil Éireann, the area of the county is currently divided into eleven constituencies: Dublin Bay North, Dublin Bay South, Dublin Central, Dublin Fingal, Dublin Mid-West, Dublin North-West, Dublin Rathdown, Dublin South-Central, Dublin South-West, Dublin West, and Dún Laoghaire. Together they return 45 deputies (TDs) to the Dáil.

The first Irish Parliament convened in the small village of Castledermot, County Kildare on 18 June 1264. Representatives from seven constituencies were present, one of which was the constituency of Dublin City.[164] Dublin was historically represented in the Irish House of Commons through the constituencies of Dublin City and County Dublin. Three smaller constituencies had been created by the 17th century: Swords; which was created sometime between 1560 and 1585, with Walter Fitzsimons and Thomas Taylor being its first recorded MPs; Newcastle in the west of the county, created in 1613; and Dublin University, which was a university constituency covering Trinity College, also created in 1613.[165] While proceedings of the Irish Parliament were well-documented, many of the records from this time were lost during the shelling of the Four Courts in July 1922.[166]

Following the Acts of Union 1800, Dublin was represented in Westminster through three constituencies from 1801 to 1885: Dublin City, County Dublin and the Dublin University. A series of local government and electoral reforms in the late 19th century radically alerted the county's political map, and by 1918 there were twelve constituencies within County Dublin.[167]

Throughout the twentieth century the representation in Dublin expanded as the population grew. In the Electoral Act 1923, the first division of constituencies arranged by Irish legislation, geographical constituencies in Dublin were 23 of the 147 TDs in geographical constituencies;[168] this contrasts with 45 of 160 at the most recent division.[169]

Twenty-three Dáil Éireann constituencies have been created and abolished within the county since independence, the most recent being the constituencies of Dublin South, Dublin North, Dublin North-Central, Dublin North-East and Dublin South-East, which were abolished in 2016.

Of the fifteen people to have held the office of Taoiseach since 1922, more than half were either born or raised within County Dublin: W. T. Cosgrave, John A. Costello, Seán Lemass, Liam Cosgrave, Charles Haughey (born in County Mayo but raised in Dublin), Garret FitzGerald, Bertie Ahern and Leo Varadkar (Cosgrave held the office of President of the Executive Council; by convention, Taoisigh are numbered to include this position). Conversely, just one of Ireland's nine presidents have hailed from the county, namely Seán T. O'Kelly, who served as president from 1945 to 1959.

European Elections

The four local government areas in County Dublin form the 4-seat constituency of Dublin in European Parliament elections.[170]

National Government

As the capital city, Dublin is the seat of the national parliament of Ireland, the Oireachtas. It is composed of the President of Ireland, Dáil Éireann as a house of representatives, and Seanad Éireann as an upper house. Both houses of the Oireachtas meet in Leinster House, a former ducal palace on Kildare Street. It has been the home of the Irish government since the creation of the Irish Free State. The First Dáil of the revolutionary Irish Republic met in the Round Room of the Mansion House, the present-day residence of the Lord Mayor of Dublin, in January 1919. The former Irish Parliament, which was abolished in 1801, was located at College Green; Parliament House now holds a branch of Bank of Ireland. Government Buildings, located on Merrion Street, houses the Department of the Taoiseach, the Council Chamber, the Department of Finance, and the Office of the Attorney General.[171]

The president resides in Áras an Uachtaráin in Phoenix Park, a stately ranger's lodge built in 1757. The house was bought by the Crown in 1780 to be used as the summer residence of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the British viceroy in the Kingdom of Ireland. Following independence, the lodge was earmarked as the potential home of the Governor-General, but this was highly controversial as it symbolised continued British rule over Ireland, so it was left empty for many years. President Douglas Hyde "temporarily" occupied the building in 1938, as Taoiseach Éamon de Valera intended to demolish it and build a more modest presidential bungalow on the site. Those plans were scrapped during The Emergency and the lodge became the president's permanent residence.[172]

Much like Áras an Uachtaráin, many of the grand estate homes of the former aristocracy were re-purposed for State use in the 20th century. The Deerfield Residence, also in Phoenix Park, is the official residence of the United States Ambassador to Ireland, while Glencairn House in south Dublin is used as the British Ambassador's residence. Farmleigh House, one of the Guinness family residences, was acquired by the government in 1999 for use as the official Irish state guest house.

Many other prominent judicial and political organs are located within Dublin, including the Four Courts, which is the principal seat of the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court and the Dublin Circuit Court; and the Custom House, which houses the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage. Once the centuries-long seat of the British government's administration in Ireland, Dublin Castle is now only used for ceremonial purposes, such as policy launches, hosting of State visits, and the inauguration of the president.[173]

Social issues and ideology

Dublin is among the most socially liberal places in Ireland, and popular sentiment on issues such as LGBT rights, abortion and divorce has often foreran the rest of the island. Referendums held on these issues have consistently received much stronger support within Dublin, particularly the south of the county, than the majority of the country.[174] While over 66% of voters nationally voted in favour of the Eighth Amendment in 1983, 58% of voters in Dún Laoghaire and 55% in Dublin South voted against it. In 2018, over 75.5% of voters in County Dublin voted to repeal the amendment, compared with 66.4% nationally.

In 1987, Dublin Senator David Norris took the Irish government to the European Court of Human Rights (see Norris v. Ireland) over the criminalisation of homosexual acts. In 1988, the Court ruled that the law criminalising same sex activities was contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights, in particular Article 8 which protects the right to respect for private life. The law was held to infringe on the right of adults to engage in acts of their own choice.[175] This led directly to the repeal of the law in 1993. Numerous LGBT events and venues are now located within the county. Dublin Pride is an annual pride parade held on the last Saturday of June and is Ireland's largest public LGBT event. In 2018, an estimated 60,000 people attended.[176] During the 2015 vote to allow same-sex marriage, 71% of County Dublin voted in favour, compared with 62% nationally.

In general, the south-eastern coastal regions of the county such as Dún Laoghaire and Dublin Bay South are a stronghold for the liberal-conservative Fine Gael party.[177] Since the late-2000s the Green Party has also developed a strong support base in these areas. The democratic socialist Sinn Féin party generally performs well in south-central and west Dublin, in areas like Tallaght and Crumlin. In recent elections Sinn Féin have increasingly taken votes in traditional Labour Party areas, whose support has been on the decline since 2016.[178] As a result of the economic crisis, centre-right Fianna Fáil failed to gain a single seat in Dublin in the 2011 general election. This was a first for the long-time dominant party of Irish politics.[179] The party regained a footing in 7 of the 11 Dublin constituencies in 2020, and were also the largest party in Dublin City, Fingal and South Dublin in the 2019 local elections.

Sport

GAA

-150293.jpg.webp)

Dublin is a dual county in Gaelic games, and it competes at a similar level in both hurling/camogie and Gaelic football. The Dublin county board is the governing body for Gaelic games within the county. The county's current GAA crest, adopted in 2004, represents Dublin's four constituent areas. The castle represents Dublin city, the raven represents Fingal, the Viking longboat represents Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown and the book of Saint Tamhlacht in the centre represents South Dublin.[180]

In Gaelic football, the Dublin county team competes annually in Division 1 of the National Football League and the provincial Leinster Senior Football Championship. Dublin is the dominant force of Leinster football, with 62 Leinster Senior Championship wins. Nationally, the county is second only to Kerry for All-Ireland Senior Football Championship titles. The two counties are fierce rivals, and a meeting between them is considered the biggest game in Gaelic football.[181] Dublin has won the All-Ireland on 31 occasions, including a record 6 in a row from 2015 to 2020.

In hurling, the Dublin hurling team currently compete in Division 1B of the National Hurling League and in the Leinster Senior Hurling Championship. Dublin is the second most successful hurling county in Leinster after Kilkenny, albeit a distant second, with 24 Leinster hurling titles. The county has seen less success in the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship, ranking joint-fifth alongside Wexford. Dublin has been in 21 All-Ireland hurling finals, winning just 6, the most recent of which was in 1938.

Within the county, Gaelic football and hurling clubs compete in the Dublin Senior Football Championship and the Dublin Senior Hurling Championship, which were both established in 1887. St Vincents based in Marino and Faughs based in Templeogue are by far the most successful clubs in Dublin their respective sports. Four Dublin football teams have won the All-Ireland Senior Club Football Championship; St Vincents, Kilmacud Crokes, UCD and Ballyboden St Enda's. Despite their historic dominance in Dublin, Faughs have never won an All-Ireland Senior Club Hurling Championship. Since the early 2010s, Dalkey's Cuala have been the county's main hurling force, and the club won back-to-back All-Ireland's in 2017 and 2018.

Soccer

.jpeg.webp)

Association football (soccer) is one of the most popular sports within the county. While Gaelic games are the most watched sport in Dublin, association football is the most widely played, and there are over 200 amateur football clubs in County Dublin.[182] Dalymount Park in Phibsborough is known as the "home of Irish football", as it is both the country's oldest stadium and the former home ground for the national team from 1904 until 1990.[183] The Republic of Ireland national football team is currently based in the 52,000 seater Aviva Stadium, which was built on the site of the old Lansdowne Road stadium in 2010. Shortly after its completion, the Aviva Stadium hosted the 2011 UEFA Europa League Final. Five League of Ireland football clubs are based within County Dublin; Bohemians F.C., Shamrock Rovers, St Patrick's Athletic, University College Dublin and Shelbourne.

Shamrock Rovers, formerly of Milltown but now based in Tallaght, are the most successful club in the country, with 21 League of Ireland titles. They were also the first Irish side to reach the group stages of a European competition when they qualified for the 2011–12 UEFA Europa League group stage. The Dublin University Football Club, founded in 1854, are technically the world's oldest extant football club.[184] However, the club currently only plays rugby union. Bohemians are Ireland's third oldest club currently playing football, after Belfast's Cliftonville F.C. and Athlone Town A.F.C. The Bohemians–Shamrock Rovers rivalry not only involves Dublin's two biggest clubs, but it is also a Northside-Southside rivalry, making it the most intense derby match in the county.[185]