County of Hanau Grafschaft Hanau | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1429 – 1736 | |||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

| Status | State of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||||

| Capital | Hanau | ||||||||||

| Government | County | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1429–1736 (with interruptions) | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1736 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Roman Catholic; 16th-century Lutheran; from mid 17th century mixed Calvinist and Lutheran; ruled by counts; language: German | |||||||||||

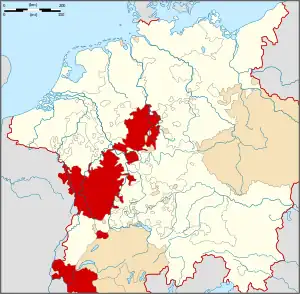

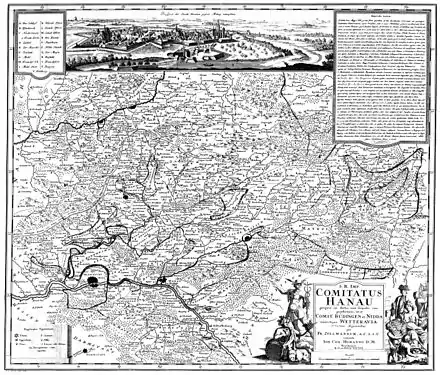

The County of Hanau was a territory within the Holy Roman Empire, evolved out of the Lordship of Hanau in 1429. From 1456 to 1642 and from 1685 to 1712 it was divided into the County of Hanau-Münzenberg and the County of Hanau-Lichtenberg. After both lines became extinct the County of Hanau-Münzenberg was inherited by the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, the County of Hanau-Lichtenberg by the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt in 1736.

Creation

In 1429 Emperor Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire declared Reinhard II. of Hanau a count, so his possessions, the Lordship (Herrschaft) of Hanau, became the County of Hanau.[1] The main part of it was positioned to the north of the river Main stretching from the East of Frankfurt am Main eastwards through the valley of the river Kinzig to Schlüchtern and into the Spessart mountains to Partenstein. Legally not correct the title County of Hanau is used in later literature sometimes also for its territorial predecessor, the Lordship of Hanau. This elevation in rank was a signal of the political and economic success of Reinhard II.

Division

Only one year after the death of Reinhard II his son and successor, Reinhard III died too, leaving as heir his son Philipp I (the younger), then a boy four years of age. It was in no way certain that he would survive long enough to produce a male heir on his own. This was a threat to the further existence of the family of the counts of Hanau. The only other living male of the family was Philipp I (the elder), a brother to Reinhard III and uncle to Philipp I (the younger). Due to the Hanau Statute of Primogeniture of 1375 only the eldest son of a reigning count of Hanau was allowed to marry and produce offspring able to inherit the title and county. This caused a conflict within the family producing two parties: The mother of Philipp I (the younger), Countess Palatine Margaret of Mosbach, and her father, Otto I, Count Palatine of Mosbach, on one side insisting on the Statute of Primogeniture. Their interest lay in securing the whole, undivided inheritance for Philipp I (the younger). On the other side stood Philipp I (the elder) and most of the influential persons and institutions in the county, including its four towns. The conflict lasted until 1457 when Countess Palatine Margaret died. In 1458 this led to the solution Philipp I (the elder) wished: The administrative District of Babenhausen – that was all the territory of the county south of the river Main – was separated from the county and given to Philipp I (the elder).[2] It became the nucleus of the county of Hanau-Lichtenberg. The remaining county was later called Hanau-Münzenberg to distinguish the two counties.

Reunification

Politics

In 1642 the last male member of the Hanau-Münzenberg family, Count Johann Ernst, died. The next male of kin was Friedrich Casimir, Count of Hanau-Lichtenberg, then still a minor under the guardianship of Georg II of Fleckenstein-Dagstuhl. The relationship to Count Johann Ernst was quite remote and the inheritance was endangered in more than one way. The inheritance happened during the final years of Thirty Years' War, the feudal Overlords, partly enemy to Hanau, tried to hold back fiefs traditionally held by Hanau-Münzenberg, the county of Hanau-Münzenberg was of Reformed Confession, Friedrich Casimir and the county of Hanau-Lichtenberg were Lutheran and even to reach the capital of Hanau-Münzenberg, the town of Hanau, proved to be very difficult for the heir: Friedrich Casimir only managed by travelling in disguise. Georg II of Fleckenstein-Dagstuhl managed the succession of Friedrich Casimir by two treaties:

- Parties to the first one of 1642 were Friedrich Casimir and the wealthy bourgeoisie of Hanau. The court granted the reformed faith as state religion within Hanau-Münzenberg only reserving Lutheran services for himself and his court. Therefore, the citizens of Hanau – by far the strongest power within the devastated county – supported the accession of Friedrich Casimir.

- Parties to the second one of 1643 were Friedrich Casimir and Landgravine Amalie Elisabeth, née countess of Hanau-Münzenberg, daughter to Philipp Ludwig II. She granted military and diplomatic support against the still resisted overlords. Therefore, Friedrich Casimir granted – should the house of Hanau be without male heirs – the inheritance of Hanau-Münzenberg to the descendants of Amalie Elisabeth.[3] That actually happened in 1736.

These treaties secured the unification of the two Hanau counties under one ruler and saved Hanau-Münzenberg as a unit.[4]

Against the treaty of accession between Friedrich Casimir and his Hanau subjects he tried to enlarge the influence of the Lutherans within Hanau-Münzenberg: The first twenty years of his reign the Lutheran services were limited to the chapel in his castle in Hanau. But due to growing numbers from 1658 to 1662 an own church building for the Lutherans was erected in the town against the protest of the reformed majority, the Johanneskirche. Both parties struggled against each other for decades, tried to prevent – unsuccessfully – mixed marriages and even fought one another. An additional treaty of 1670 allowed the Lutherans their own church. This resulted in two parallel churches within the county of Hanau-Münzenberg each one having its own administration. Therefore, a lot of villages in Hanau-Münzenberg had a set of reformed church, school, vicarage and cemetery and another one for the Lutherans.[5] Only the Enlightenment and the economic crises of the Napoleonic Wars let to the Hanau Union which ended this double structure in 1818.

Sibylle Christine of Anhalt-Dessau, the widow of Count Philipp Moritz, who had been the ruling count until 1638 had received Steinau Castle as her widow seat. As widow of a ruling count, she could raise substantial claims against the county. To avoid this, it was decided to marry Friedrich Casimir to the widow, who was 44 years old at the time, almost 20 years older than he. An added advantage of this marriage was that she was a Calvinist which calmed the majority of the population. The marriage was plagued by differences. The marriage with the elderly widow remained childless. Shortly before his death, Friedrich Casimir adopted his nephew count Philipp Reinhard.[6]

Economy

Friedrich Casimir tried to implement mercantilism into his county severely devastated by the effects of Thirty Years' War. A leading role in this is claimed for his adviser Johann Becher. A successful achievement was the foundation of a factory to produce Faience, the first in Germany. On the other hand, the count's extravagant initiative to lease Guiana from the Dutch West India Company was a devastating experiment. These Hanauish-Indies (Hanauisch-Indien) never became a reality but nearly let his county into bankruptcy. So in 1670 his nearest relatives staged a palace revolution trying to kick Friedrich Casimir out of office. This did not work entirely. But Friedrich Casimir was put under the guardianship of his relatives by emperor Leopold and the count's possibilities to stage new experiments were severely curtailed.[7]

The last counts of Hanau

Friedrich Casimir died childless in 1685. His inheritance was divided between his two male nephews, count Philipp Reinhard, who inherited Hanau-Münzenberg and count Johann Reinhard III, who inherited Hanau-Lichtenberg. Both were sons of Friedrich Casimir's brother count Johann Reinhard II. So the county of Hanau was divided again into two, Hanau-Münzenberg and Hanau-Lichtenberg as it was before 1642. But when in 1712 Count Philipp Reinhard died, Count Johann Reinhard III inherited the county of Hanau-Münzenberg and for a last time both counties were united into one county of Hanau. Count Johann Reinhard III, the last male member of the Hanau family died in 1736. Hanau-Münzenberg and Hanau-Lichtenberg fell to different heirs: Due to the treaty of succession of 1643 Hanau-Münzenberg was inherited by the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, Hanau-Lichtenberg fell to the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt because Countess Charlotte of Hanau-Lichtenberg, daughter to Johann Reinhard III, was married to the heir of Hesse-Darmstadt, reigning later as landgrave Louis VIII.[8]

The question of whether the administrative district of Babenhausen was part of Hanau-Münzenberg or Hanau-Lichtenberg nearly lead to war between the two Landgraviates in 1736; an extensive legal suit began at the Imperial Chamber Court, one of the two highest courts of the Holy Roman Empire. The suit ended with a compromise to partition Babenhausen equally between them. However, it took until 1771 to realize this.[9]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 34.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 119–126.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 192–194.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 96, 155–158, 189–191.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 140–151.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 117.

- ↑ Reinhard Dietrich: … wegen geführten großen Staats, aber schlechter Zahlung der Schulden …. Zur finanziellen Lage der Grafschaft Hanau im 17. Jahrhundert. In: Hanauer Geschichtsblätter. 31, Hanau 1993, p. 123–148; Ferdinand Hahnzog: Das Hanauer „tolle Jahr“ 1669. In: Hanauer Geschichtsblätter. 20, 1965, p. 129–146.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 202–207.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 206–208.

Sources

- Reinhard Dietrich, Die Landesverfassung in dem Hanauischen. Die Stellung der Herren und Grafen in Hanau-Münzenberg aufgrund der archivalischen Quellen (= Hanauer Geschichtsblätter 34). Selbstverlag des Hanauer Geschichtsvereins, Hanau 1996, ISBN 3-9801933-6-5.

- Ernst Julius Zimmermann: Hanau, Stadt und Land. Kulturgeschichte und Chronik einer fränkisch-wetterauischen Stadt und ehemaligen Grafschaft. Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der älteren Zeit. Vermehrte Ausgabe. Selbstverlag, Hanau 1919 (Unveränderter Nachdruck. Peters, Hanau 1978, ISBN 3-87627-243-2).