When the German Empire came into existence in 1871,[1] none of its constituent states had any overseas colonies. Only after the Berlin Conference in 1884 did Germany begin to acquire new overseas possessions,[2][3] but it had a much longer relationship with colonialism dating back to the 1520s.[4][5]: 9 Before the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, various German states established chartered companies to set up trading posts; in some instances they also sought direct territorial and administrative control over these. After 1806, attempts at securing possession of territories overseas were abandoned; instead, private trading companies took the lead in the Pacific[6] while joint-stock companies and colonial associations initiated projects elsewhere, although many never progressed beyond the planning stage.[7][8]

Holy Roman Empire (to 1806)

Before 1871 there were many instances of German people migrating to live outside their native land, for example the Volga Germans invited to Russia by Catherine the Great[9] or the Palatines to the American colonies.[10] In addition, some princes of German states were involved in colonial ventures through leasing professional troops for use in the colonies of European powers, such as during the American Revolutionary War.[11] Thus, Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg established the Württemberg Cape Regiment for the Dutch East India Company[12] while the princes of Waldeck set up regiments for colonial use and even served in them.[13] Various Hessian regiments also fought with the British during the American War of Independence.[14]

In the mid-seventeenth century, the main motivation for German states seeking to establish colonial ventures was to rebuild their economies in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War. With trade and agriculture in many parts of Germany severely affected and the population greatly reduced, the lucrative Atlantic slave trade in particular appeared to offer the prospect of rapid financial recovery.[15][16] The main inspiration for German state initiatives was the Dutch Republic which had rapidly transformed itself from a minor state to a world commercial and naval power; various German rulers wished to emulate its example.[17][18][19]

Little Venice (Venezuela)

The first German colonial project was a private business initiative. Emperor Charles V ruled German territories as well as the Spanish Empire, and he was deeply in debt to the Welser family of Augsburg. In lieu of repayment the Welsers accepted a grant of land on the coast of present-day Venezuela in 1528, which they called "Little Venice". A small number of German settlers and a larger number of slaves were sent to the colony. Most of the Germans died, and the governors devoted most of their energies to expeditions into the interior to search for El Dorado. In 1556, the Spanish crown revoked the Welsers' privilege and resumed control of the territory.[4][20][21] The Welsers were treated as heroes in much 19th century German fiction, and regarded as an inspiration for German colonial projects in the 1880s and 1890s.[22]

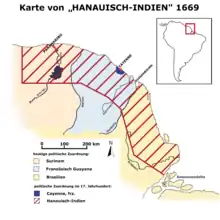

The Hanau-Indies

In 1669 the Dutch West India Company and the County of Hanau entered into a contract leasing a territory of around 100,000 square kilometres between the Orinoco and Amazon rivers in Dutch Guiana to Hanau. This territory was to be many times larger than Hanau itself (which was just under 1,400 square kilometres).[23][24] The intention was to compensate for the financial hardships of Hanau by achieving a positive trade balance with a colony. The contract secured extensive rights for the Dutch West India Company, including a monopoly on transport with the Hanau-Indies. However, from the outset there was a lack of resources to finance a project in this scale, and a lack of people willing to colonise it. The project ended in a financial fiasco for the county of Hanau. An attempt to sell it to King Charles II was not successful, and the project finally failed due to the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Dutch War the same year.[25]

Bavarian projects

In 1657 the Bavarian scholar Johann Joachim Becher published a Call for the Founding of German Overseas Colonies (Aufruf zur Gründung deutscher Überseekolonien), but this found no immediate support. The Bavarian Elector Ferdinand Maria was interested in a project to colonise New Amsterdam, but after the Dutch Republic ceded the territory to England, the Bavarian scheme was abandoned in 1675.[26] There are accounts that in the early 1730s, there was a plan for the Elector Maximilian II Emanuel to take possession of a tract of land in Guiana on the Barima River to establish a Bavarian colony,[27] however no documentary evidence of such a plan has ever emerged.[28]

Brandenburg-Prussian colonies

Early ventures

The colonial ambitions of Brandenburg-Prussia began under Frederick William the Great Elector who had studied at the Dutch universities of Leyden and the Hague.[29]: 8 When Frederick William became elector in 1640, he invited Dutch engineers to Brandenburg, sent Brandenburg engineers to study in the Netherlands, and in 1646 married Luise Henriette of the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau. He engaged former Dutch admiral Aernoult Gijsels van Lier as his advisor and tried to persuade the Holy Roman Emperor and other princes of the empire to participate in the creation of a new East India Company.[29]: 8–10 The Emperor declined as he considered it dangerous to disturb the interest of the other European powers. In 1651, Frederick William agreed to purchase the Danish possessions of Fort Dansborg and Tranquebar in India for 120,000 reichstalers, but as he was ultimately unable to raise this sum, the agreement was cancelled in 1653.[29]: 9–11

Brandenburg slaving

In 1680, the first slaving ship sailed from Brandenburg to Africa. Lacking a port on the North Sea, the Brandenburgers embarked from Pillau on the Baltic; in 1683, an agreement was signed with the city of Emden giving them access to the North Sea.[30] In 1682, at the suggestion of the Dutch merchant and privateer de:Benjamin Raule, Frederick William granted a charter to the (de) Brandenburg Africa Company (BAC), marking the first organised and sustained attempt by a German state to take part in the Atlantic slave trade. With his state still impoverished after the Thirty Years War, the Elector hoped to replicate the mercantile successes of the Dutch East India Company.[30] In 1683 the red eagle of Brandenburg was hoisted over Cape Three Points in present-day Ghana, and the first "treaties of protection" were signed with local chiefs. In addition, the foundation stone was laid for de:Fort Groß Friedrichsburg. In 1687, Prussia signed a treaty with the Emir of Trarza which allowed it to use the fort of Arguin for supplies and trading - gum arabic was also an important secondary trade commodity for the Prussians.[30] Other goods traded included ivory, gold and salt.

To provide a market for slaves imported from Africa, Frederick William needed a base in the Caribbean. In 1684, Brandenburg-Prussia was denied the purchase of the French islands of Sainte-Croix and Saint-Vincent.[31]: 15 In November 1685, after a failed attempt to purchase Saint Thomas from Denmark–Norway,[31]: 15 an agreement was reached that allowed the Brandenburg African Company to lease part of Saint Thomas as a base for 30 years, while sovereignty rested with Denmark and administration with the Danish West India Company. Brandenburg-Prussia was allotted an area near the capital city Charlotte Amalie, called Brandenburgery, and other territories named Krum Bay and Bordeaux Estates further west.[31]: 16 The first Brandenburg ship arrived at St. Thomas in 1686 with 450 slaves from Groß Friedrichsburg. In 1688, 300 Europeans and several hundred slaves lived on the Brandenburg estates.[31]: 17 The demand for slaves on Caribbean plantations always exceeded the capacity of the fleets of European traders to deliver more captives, so there was a reliable market for Prussia to sell slaves. Between 1682 and 1715, the Prussians landed at least 19,240 slaves in the various European colonies in the Caribbean.[30]

Peak trade and decline

Brandenburg-Prussia tried to acquire other Caribbean territories to develop its slave trade. It attempted to take Crab Island in 1687, but the island was also claimed by several other European powers, and when a second expedition in 1692 found the island in Danish hands, the plan was abandoned. In 1689, Brandenburg-Prussia annexed Peter Island, but the small rock proved useless for trade or settlement.[31]: 22 In 1691, Brandenburg-Prussia and the Duchy of Courland agreed to partition of Tobago, but since Courland was no longer present on the island which had in the meantime been claimed by England, the agreement was nullified, and negotiations with England yielded nothing. In 1695, Brandenburg-Prussia tried to purchase Tortola, but England rebuffed their offer. Likewise, England declined an offer to purchase Sint Eustatius in 1697.[31]: 22

After a short period of prosperity a gradual decline of the colonies began after 1695. The reasons for this lay partly in the limited financial and military resources available to Brandenburg-Prussia, but also in the determination of the French to drive out an effective commercial rival. The BAC never had more than sixteen ships at any time, and between 1693 and 1702, fifteen ships were lost to French attacks.[30] In November 1695, French forces looted the Brandenburg (but not the Danish) colony on Saint Thomas. In 1731, the Brandenburg-Prussian company on Saint Thomas became insolvent, and abandoned the island in 1735. Their last assets were sold at auction in 1738.[31]: 21–23

The grandson of Frederick William, King Frederick William I of Prussia, had no personal ties or inclinations to sustain a navy and colonies and focused more on the expansion of the Prussian army, on which the greater part of the financial resources of the Prussian state were spent. In 1717 he revoked the charter of the BAC and by treaties in 1717 and 1720, sold his African colonies to the Dutch West India Company for 7,200 ducats and 12 "Moors".[32] Frederick the Great invested 270,000 taler in the Emden Company, a new Asiatic-Chinese trading company in Emden in 1751, but otherwise took no interest in colonies.[26]

Between 1774 and 1814, de:Joachim Nettelbeck, a popular hero, made several attempts to persuade Prussia to return to colonial politics. Among other things, he wrote a memorandum recommending the occupation of a not yet colonised coastal strip on the Courantyne River between the Berbice and Suriname. Neither Frederick the Great nor Frederick William II seriously considered Nettelbeck's proposals.[26]

Austrian trade and colonies

Ostend Company

In 1714 Spain ceded control of its territories in the north of Europe, which then became the Austrian Netherlands. This gave the Austrians access to the North Sea for the first time. The Ostend East-India Company was chartered by the Emperor Charles VI in December 1722 on the model of the Dutch East India Company.[33] The capital of 6 million guilders, was mainly supplied by the inhabitants of Antwerp and Ghent.[34] The seven directors were chosen from leading figures in trade and finance: Jacques De Pret, Louis-François de Coninck and Pietro Proli, from Antwerp; Jacques Maelcamp, Paulo De Kimpe and Jacques Baut, from Ghent; and the Irish Jacobite Thomas Ray, a merchant and banker based in Ostend.[35]

The company possessed two trading posts, at Cabelon on the Coromandel Coast and Banquibazar in Bengal. Between 1724 and 1732, 21 company vessels were sent out, mainly to Bengal and Guangzhou. Thanks to the rise in tea prices, great profits were made in the China trade. Between 1719 and 1728, the Ostend Company transported 7 million pounds of tea from China (roughly half of the total amount brought to western Europe), about the same as East India Company during the same period.[36]

The commercial success of the company irked the established traders of the other European East India companies, who made every effort to hinder its activities. Following the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, the main foreign policy objective of Emperor Charles VI was to secure international agreement to the succession of his daughter Maria Theresa. However, both Britain and the Dutch Republic refused to do this while the Ostend Company continued to operate. Eventually, in May 1727, the Emperor suspended its charter for seven years and, in March 1731, under the terms of the Second Treaty of Vienna, agreed its final abolition. This secured British and Dutch agreement to his succession plans.[36] The company officially ceased trading on 16 February 1734, and was wound up on 16 February 1737.[34] The factory at Banquibazar was retained until the 1740s under direct Imperial ownership.[37]

Austrian East India Company

In 1776 Colonel William Bolts, formerly of the Honourable East India Company, approached Maria Theresa of Austria with a proposal to found a company to explore trade with Africa, India, and China.[38] She agreed, granting a ten-year charter to the newly-formed Austrian Asiatic Company of Trieste with Bolts at its head.[39]

In 1776 Bolts sent the Joseph und Theresia to the Nicobar Islands, which had previously been colonised by Denmark but then abandoned.[40] In June 1778 the ship reached Nancowry Island and on 12 July the captain signed a treaty with Nicobarese chiefs ceding all of the islands to Austria.[41] The ship then sailed away, leaving 6 settlers behind with slaves and cattle to start the new Austrian colony.[42] They were left to their own devices until 1783, when the Danish sent a warship from Tranquebar to remove them, and the survivors abandoned the colony soon after.[43]

Meanwhile, Bolts himself sailed to Africa. In 1778, he docked in Delagoa Bay (in modern Mozambique), where he made treaties with the local Mabudu chieftains.[44] A trading post was built, dealing in ivory, and profits reached as high as 75,000 pounds per year.[45] The Austrian trade in Delagoa Bay caused the ivory price to rise sharply dramatically[38] prompting the Portuguese to expel the Austrian colonists, which they did in 1781.[44]

In serious financial difficulties, the company was reconstituted in the summer of 1781 as the new Imperial Company of Trieste and Antwerp for Asian Commerce (Société Impériale pour le Commerce Asiatique de Trieste et d’Anvers), with Bolts no longer in charge.[46] The new company focused on the China tea trade, particularly lucrative since the American War of Independence meant that few British, Dutch or French ships were sailing to Asia. As a neutral country, Austria could be sure that its ships would not be attacked on the high seas. However, with the Treaty of Paris normal trading resumed, the price of tea dropped dramatically, and in 1785 the company was declared bankrupt.[47]

Danish colonies-Altona and the slave trade

In the 18th and 19th centuries the Duchy of Holstein was part of the Holy Roman Empire and the German Confederation, although its duke was the king of Denmark. In particular, the Holstein city of Altona, not yet part of Hamburg, maintained a lively trade with the Danish West Indies.[48] It was an important centre for the cowrie trade - French slavers in particular purchased cowries sourced in the Indian Ocean, exchanged in Altona, and used to buy slaves in West Africa.[49] On 9 April 1764 Frederick V of Denmark issued an edict granting the privilege of engaging in the slave trade to his subjects in Altona and the other royal enclaves of Holstein, authorising them also to use foreign goods for the purpose. Danish subjects were entitled to a remission of the customs duty on any slaves purchased in Africa who were to be used on Danish plantations in the Caribbean.[50] Slaving ships were departing for West Africa from Altona as late as 1841.[51]

German Confederation (1806-1871)

Colonies and German national consciousness

Calls for colonial expansion were central to German liberals’ efforts to establish their concept of the nation-state.[5]: 9–10 Indeed, in discussions about national identity, Liberals' emphasis on the symbolically important question of colonies was central to their assertion of social, cultural and political hegemony in Germany.[52]

On 2 February 1806, in Tübingen the student Carl Ludwig Reichenbach founded a secret Otaheiti Society for the establishment of a colony in the South Seas in Tahiti, together with Carl and Wilhelm Georgii, the Kurz brothers, Georg Sellner, Immanuel Hoch, Christian Klaiber, Friedrich Hölder and Christian Friedrich Hochstetter. At the end of 1808, the group was discovered by the police who arrested most of its members on suspicion of high treason.[53]

In 1828 a group of settlers founded the estate of Askania-Nova in present-day Ukraine as a colony leased to the German Duchy of Anhalt-Köthen. In the first ten years sheep farming was successfully carried on. However, due to financial mismanagement, the colony had to be repeatedly bailed out by the Duchy. It passed into the possession of the Duke of Anhalt-Dessau and was eventually sold in 1856 to a German-Russian nobleman.[54][55]

During the period of the short-lived German Empire of 1848-1849, enthusiasm for establishing colonies increased significantly and colonial societies were founded in Leipzig and Dresden, followed by others in Darmstadt, Wiesbaden, Hanau, Hamburg, Karlsruhe and Stuttgart.[56] In June 1848 Richard Wagner wrote "Now we want to travel in ships over the sea, here and there to found a young Germany".[57][58]

German settlements in South America

Brazil

.jpg.webp)

João VI, king of Portugal and Brazil encouraged European settlers to Brazil. In a decree of 1808 he opened the country to non-Portuguese immigration and granted non-Catholics the right to own land. He particularly wanted Europeans to settle the south of the country where few but indigenous people lived. Continuing this policy after Brazil declared independence, João's successor Pedro I of Brazil also sought new, loyal soldiers who would support him in the event that those of Portuguese origin turned against him. Dom Pedro's wife was a Habsburg, Maria Leopoldina of Austria, and her confidant Major Georg Anton Schäffer was sent to Germany to recruit colonists. Dom Pedro offered them free passage to Brazil and free land in Rio Grande do Sul. By the end of 1824, some 2,000 German-speakers had emigrated to Brazil, and another 4,000 followed by 1830.[5]: 57–59

In 1827, Karl Sieveking concluded a trade agreement for Hamburg merchants in Rio de Janeiro.[59] On 30 March 1846, he warned Hamburg traders that the Bremen Senate was planning to extend its activities into South America. Anxious not to lose their pre-eminent position, a group of them founded a "Society for the Promotion of Emigration to the Southern Provinces of Brazil" in the autumn of 1846.[60] Sponsoring companies included Chr. Matt. Schröder & Co, CJ John's sons, Ross, Vidal & Co, Rob. M. Sloman, AJ Schön & Söhne and A. Abendroth. Adolph Schramm was sent to Rio de Janeiro for negotiations, but these proved protracted; on 30 June 1847, Sieveking died and with the general political situation in Germany deteriorating, the "Society for the Promotion of Emigration to the Southern Provinces of Brazil" was quietly dissolved in the autumn of 1847.[61]: 299–300

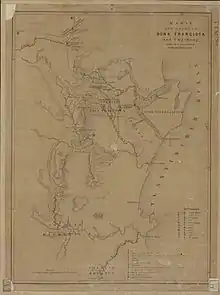

By 1849, conditions for founding a new colony had improved. The Prince of Joinville had received large estates in the province of Santa Catarina as the dowry of his wife Francisca, daughter of Dom Pedro, and he was keen to settle them. Previously, as the son of the French king, he had not welcomed the idea of large-scale German colonisation; following the deposition of Louis-Philippe I he was more amenable. However, there were now fewer Hamburg merchants willing to commit to the enterprise - the new "Colonization Association of 1849 in Hamburg" attracted fewer partners than its predecessor. It was founded by Fa. Chr. Matth. Schröder & Co and Adolph Schramm, with Friedrich Gültzow and Ernst Merck joining later.[61]: 309–310

The area for colonisation was smaller than the one planned three years earlier. The Association undertook to settle a fixed number of colonialists each year, and slave labor was explicitly excluded. The colony was to be named "Dona Francisca" in honour of the Princess of Joinville, with the first city to be called "Joinville". Between 1851 and 1856 the settlement grew to 1,812 members. By this time however the capital of the Colonization Association was almost exhausted and in 1857 Fa. Chr. Matth. Schröder & Co ceased trading. Thereafter the Brazilian government took over the payment of bonuses to the colonists. By 1870 the colony had 6500 inhabitants.[61]: 316–320

Chile

From 1850 to 1875 the region around Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue in Southern Chile received some 6,000 German immigrants as part of a state-led colonization scheme.[62] Some immigrants were leaving Europe as consequence of the aftermath of the German revolutions of 1848–49.[63] They brought skills and assets as artisans, farmers and merchants to Chile, contributing to development.[62] Initial immigration was promoted by German expatriate Bernhard Eunom Philippi whose project Chilean authorities adopted in the late 1840s.[63] Germans and German-Chileans developed trade across the Andes, controlling mountain passes establishing the settlement from which Bariloche in Argentina grew out.[64]

Settlement in Chile had little to do with the German state as the migration preceded the formation of modern Germany in 1871.[65]

The Chatham Islands

_(14760621401).jpg.webp)

The German Colonization Society was another company established by Hamburg merchants, in 1842, to found a German colony on the Chatham Islands, about 650 km southeast of New Zealand's North Island. On 12 September 1841, a memorandum had been signed in Hamburg by John Ward for the New Zealand Company and Karl Sieveking for the still-to-be established German Colonisation Society to purchase the Chatham Islands for 10,000 pounds sterling on the basis that the Crown had never formally claimed sovereignty over them. Ratification of the agreement was to be completed within 6 months.[7] In November, Sieveking published a booklet with various reports on the Chathams under the title "Warrekauri" and a prospectus entitled "The German Antipodes Colony". In December 1841, the Hamburg press reported on the project positively, although papers elsewhere were negative.[66]

Although the New Zealand Company had been told in early December 1841 to end the arrangement as the Crown would not relinquish sovereignty, Ward continued to negotiate.[67] On 15 February 1842, a provisional committee met to found the German Colonisation Society. It consisted of Karl Sieveking, August Abendroth, De Chapeaurouge & Co., Joh. Ces. Godeffroy & Son, de:Eduard Johns, Ross, Vidal & Co., Schiller Brothers & Co., Adolph Schramm and Robert Miles Sloman.[68]

After the Crown became aware of the project, it had its chargé d'affaires in Hamburg inform Sieveking that John Ward was not authorised to enter into negotiations and letters patent signed by Queen Victoria on 4 April 1842, confirmed that the Chatham Islands were part of the colony of New Zealand. The agreement of 12 September 1841, could thus not be fulfilled and on 14 April, the provisional committee dissolved itself.[67]

Expanding trade and the navy

German colonial policy after 1848 was driven by commercial considerations. Unlike neighbouring countries, there was no strong impetus towards missionary activities or the Germanisation of indigenous peoples as an inherent good.[8]: 3 In the 1850s and 1860s, the first German commercial enterprises were established in Africa, Samoa and the north-eastern part of New Guinea.[6] For example, in 1855 J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn expanded its business into the Pacific.[69] Its Valparaiso agent August Unshelm sailed to the Samoan Islands, following which German influence expanded with plantations for coconut, cacao and hevea rubber, especially on the island of Upolu where German firms monopolised copra and cocoa bean processing. In 1865 J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn obtained a 25-year lease to the eastern islet of Niuoku of Nukulaelae Atoll (in modern Tuvalu).[70] These commercial ventures later formed the basis for annexations under the German Empire, but before 1871 the government maintained a firm policy of avoiding colonial expansion.

The Austrian government maintained a similar stance against the establishment of colonies. In 1857 Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria sent the "SMS Novara" on a scientific expedition to sail around the world. In February 1858, the Novara reached Car Nicobar. The expedition leader Karl von Scherzer then began promoting the idea of a renewed Austrian colonisation plan, which the government rejected.[41]

Proposals for Germany to take various territories continued to appear periodically, including one for the annexation of Formosa and another for a renewed settlement of Germans under colonial government in the Nicobar Islands,[8]: 7–11 but all such initiatives were repeatedly rebuffed by the German government on the grounds of expense and a desire not to antagonise Britain. For example, German traders in Fiji put forward a proposal for the annexation of the islands, but Bismarck rejected it in March 1870[8]: 8 although he did appoint a consul.[71]

The establishment of the Imperial fleet eventually created a naval power that would be able to enforce colonial aspirations. In 1848 both the Hamburg Naval Commission and Prince Adalbert of Prussia as head of the Technical Naval Commission in his "Memorandum on the formation of a German fleet" called for the establishment of German fleet bases around the world to protect German trade.[72] With the dissolution of the empire the following year, these colonial ambitions could not be realised, but in 1867 Adalbert of Prussia became commander of the Navy of the North German Confederation and began setting up the overseas naval stations planned in 1848, thereby finally providing the required military infrastructure for the future acquisition of German colonies.

See also

References

- ↑ Mark Allinson (30 October 2014). Germany and Austria since 1814. Routledge. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-4441-8652-9.

- ↑ Brantlinger, Patrick (1985). "Victorians and Africans: The Genealogy of the Myth of the Dark Continent". Critical Inquiry. 12 (1): 166–203. doi:10.1086/448326. JSTOR 1343467. S2CID 161311164.

- ↑ R. Robinson, J. Gallagher and A. Denny, Africa and the Victorians, London, 1965, p. 175.

- 1 2 Labell, Shellie. "Sixteenth-Century German Participation in New World Colonization: A Historiography". academia.edu. academia.edu. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 Cassidy, Eugene (2015). Germanness, Civilization, and Slavery: Southern Brazil as German Colonial Space (1819-1888) (PDF) (PhD). University of Michigan. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- 1 2 Washausen, Helmut (1968). Hamburg und die Kolonialpolitik des Deutschen Reiches. [Hamburg and Colonial Politics of the German Empire]. Hamburg: Hans Christians Verlag. pp. 67–114.

- 1 2 Frankfurter Ober-Post-Amts-Zeitung: 1842,1/3. Thurn & Taxis. 1842. p. 499.

- 1 2 3 4 Arthur J. Knoll; Hermann J. Hiery (10 March 2010). The German Colonial Experience: Select Documents on German Rule in Africa, China, and the Pacific 1884-1914. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-5096-0.

- ↑ Fred C. Koch, The Volga Germans: in Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the present, Penn State Press, 2010.

- ↑ Peter R. Eisenstadt (2005). The Encyclopedia of New York State. Syracuse University Press. pp. 639–. ISBN 978-0-8156-0808-0.

- ↑ German Historical Institute in London (1999). Rethinking Leviathan: The Eighteenth-century State in Britain and Germany. German Historical Institute. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-920189-1.

- ↑ "Württemberg Regiment". Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Vol. 11. Nasou Limited. 1971. pp. 546–7. ISBN 978-0-625-00324-2.

- ↑ Eelking, Max von (1893). The German Allied Troops in the North American War of Independence, 1776–1783. Translated from German by J. G. Rosengarten. Joel Munsell's Sons, Albany, NY. p. 257. LCCN 72081186.

- ↑ Atwood, Rodney (1980). The Hessians: Mercenaries from Hessen-Kassel in the American Revolution. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "Graf Friedrich Casimir von Hanau". Hesse’s (post)colonial. University of Giessen. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ (Ed.) Oneida-Tutu, John Kwadwo; (Ed.)Smith, Victoria Ellen (2018). Shadows of Empire in West Africa. New Perspectives on European Fortifications. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-319-39281-3. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ↑ Pamela H. Smith (20 September 2016). The Business of Alchemy: Science and Culture in the Holy Roman Empire. Princeton University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4008-8357-8.

- ↑ Skalweit, Stephen. "Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg". britannica.com. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ Wendy Sutherland (15 May 2017). Staging Blackness and Performing Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century German Drama. Taylor & Francis. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-317-05085-8.

- ↑ "Koloniale Aktivitäten der Welser". fuggerandwelserstreetdecolonized.wordpress.com. 2 April 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ↑ "Bartholomeus Welser". newadvent.org. Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ↑ Montenegro, Giovanna (2018). ""The Welser Phantom": Apparitions of the Welser Venezuela Colony in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century German Cultural Memory". Transit. 2 (2). Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ↑ Gisela Graichen, Horst Gründer: Deutsche Kolonien - Traum und Trauma. Berlin, 2nd edition, 2005, p.23

- ↑ Ferdinand Hahnzog: Hanauisch-Indien, Hanau 1959 p.21.

- ↑ "Hanauisch-Indien". Hgv1844.de. Hanauer Geschichtsverein. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 Horst Gründer (19 February 2018). Geschichte der deutschen Kolonien. UTB. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-8252-4972-4.

- ↑ Odeen Ishmael (December 2013). THE TRAIL OF DIPLOMACY. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-1-4931-2654-5.

- ↑ Burr, George Lincoln (1900). "The Guiana Boundary: A Postscript to the Work of the American Commission". The American Historical Review. 6 (1): 49–64. doi:10.2307/1834689. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t2988sk9d. JSTOR 1834689.

- 1 2 3 van dear Heyden, Ulrich (2001). Rote Adler an Afrikas Küste. Die brandenburgisch-preussische Kolonie Grossfriedrichsburg in Westafrika. Selignow. ISBN 978-3-933889-04-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Felix Brahm; Eve Rosenhaft (2016). Slavery Hinterland: Transatlantic Slavery and Continental Europe, 1680-1850. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 26–30. ISBN 978-1-78327-112-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carreras, Sandra; Maihold, Günther (2004). Preußen und Lateinamerika. Im Spannungsfeld von Kommerz, Macht und Kultur. Europa-Übersee. LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8258-6306-7.

- ↑ Sebastian Conrad: Deutsche Kolonialgeschichte. C.H. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56248-8, p.18.

- ↑ S. H. Steinberg (17 April 2014). A Short History of Germany. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-1-107-66016-8.

- 1 2 J. Mertens, "Oostende – Kanton – Oostende, 1719–1720", in Doorheen de nationale geschiedenis (State Archives in Belgium, Brussels, 1980), pp. 224-228.

- ↑ Baguet, Jelten (2015). "Politics and commerce: a close marriage? The case of the Ostend Company (1722-1731)". Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis. 12 (3): 51–76. doi:10.18352/tseg.63.

- 1 2 Butel, Paul (1997). Européens et espaces maritimes: vers 1690-vers 1790. Bordeaux University Press. p. 198.

- ↑ Keay, John (1991). The Honourable Company. A History of the English East India Company. London: Macmillan. p. 241. ISBN 978-0736630481.

- 1 2 Kloppers, Roelie J. (2003). The History and Representation of the History of the Mabudu-Tembe (Thesis). Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ Octroi de Sa Majesté l’Imperatrice Reine Apostolique, accordé au Sieur Guillaume Bolts, à Vienne le 5 Juin 1775”, Guillaume Bolts, Recueil de pièces authentiques, relatives aux affaires de la ci-devant Société impériale asiatique de Trieste, gérées à Anvers, Antwerp, 1787, pp.45-49

- ↑ Stow, Randolph (1979). "Denmark in the Indian Ocean, 1616-1845". ro.uow.edu.au. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- 1 2 Steger, Philipp (2005). "The Nicobar Islands: Linking Past and Future". University of Vienna. Archived from the original on 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ↑ Lowis,R. F. (1912) The Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- ↑ Walter Markov, “L'expansion autrichienne outre-mer et les intérêts portugaises 1777-81”, Congresso Internacional de História dos Descobrimentos, Actas, Volume V, II parte, Lisboa, 1961, pp.281-291.

- 1 2 Liesegang, Gerhard (1970). "Nguni Migrations between Delagoa Bay and the Zambezi, 1821-1839". African Historical Studies. 3 (2): 317–337. doi:10.2307/216219. ISSN 0001-9992. JSTOR 216219.

- ↑ D., Newitt, M. D. (1995). A history of Mozambique. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253340061. OCLC 27812463.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ David Macpherson, The History of the European Commerce with India, London, 1812, p.316.

- ↑ Franz von Pollack-Parnau, "Eine österreich-ostindische Handelskompanie, 1775-1785: Beitrag zur österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte unter Maria Theresia und Joseph II"

- ↑ Petra Schellen: Altona, gebaut aus Sklaven-Gold, in: taz, 12 June 2017, accessed 16 September 2017.

- ↑ Jan Hogendorn; Marion Johnson (18 September 2003). The Shell Money of the Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-0-521-54110-7.

- ↑ Green-Pedersen, Sv.E. (1971). "The scope and structure of the Danish negro slave trade". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 19 (2): 167. doi:10.1080/03585522.1971.10407697.

- ↑ The British and Foreign Anti-slavery Reporter. Lancelot Wild. 1840. p. 2.

- ↑ Matthew P. Fitzpatrick (2008). Liberal Imperialism in Germany: Expansionism and Nationalism, 1848-1884. Berghahn Books. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84545-520-0.

- ↑ "Reichenbach, Karl L. Von". CERL Thesaurus. Consortium of European Research Libraries. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ↑ Schwahn, Hans. "Askania Nova". landesarchiv.sachsen-anhalt.de. Landesarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ↑ Susanna Forrest (2 May 2017). The Age of the Horse: An Equine Journey Through Human History. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8021-8951-6.

- ↑ Johanna Elisabeth Becker: Die Gründung des Deutschen Kolonialinstituts in Hamburg. Hamburg 2005, p.6

- ↑ Jutta Bückendorf (1997). 'Schwarz-weiss-rot über Ostafrika !': deutsche Kolonialpläne und afrikanische Realität. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 161. ISBN 978-3-8258-2755-7.

- ↑ Wilhelm Tappert (27 April 2016). Richard Wagner - sein Leben und seine Werke. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 37. ISBN 9789925005666.

- ↑ Diplomatisches Archiv für die Zeit- und Staatengeschichte. Cotta. 1828. p. 121.

- ↑ Schramm, Percy Ernst (1964). "Das Projekt einer deutschen Siedlungskolonie in Südbrasilien, in Angriff genommen 1846, steckengeblieben 1847". Neun Generationen: Dreihundert Jahre deutscher "Kulturgeschichte" im Lichte der Schicksale einer Hamburger Bürgerfamilie (1648–1948). Vol. 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 120–139.

- 1 2 3 Schramm, Percy Ernst (1964). "Die deutsche Siedlungskolonie Doña Francisca (Brasilien: St. Catharina) im Rahmen gleichzeitiger Projekte und Verhandlungen" (PDF). Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas/Anuario de Historia de América Latina (JbLA). 1 (1): 283–324. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- 1 2 Bernedo Pinto, Patricio (1999), "Los industriales alemanes de Valdivia, 1850-1914" (PDF), Historia (in Spanish), 32: 5–42

- 1 2 George F. W., Young (1971), "Bernardo Philippi, Initiator of German Colonization in Chile", The Hispanic American Historical Review, 51 (3): 478–496, doi:10.2307/2512693, JSTOR 2512693

- ↑ Muñoz Sougarret, Jorge (2014). "Relaciones de dependencia entre trabajadores y empresas chilenas situadas en el extranjero. San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina (1895-1920)" [Dependence Relationships between Workers and Chilean Companies located abroad. San Car-los de Bariloche, Argentina (1895-1920)]. Trashumante: Revista Americana de Historia Social (in Spanish). 3: 74–95. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ Penny, H. Glenn (2017). "Material Connections: German Schools, Things, and Soft Power in Argentina and Chile from the 1880s through the Interwar Period". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 59 (3): 519–549. doi:10.1017/S0010417517000159. S2CID 149372568.

- ↑ Die projektierte Hanseatische Kolonie auf der Chatham-Insel, (in drei Abschnitten). In August von Binzer: Allgemeines Organ für Handel und Gewerbe und damit verwandte Gegenstände, volume 7 (Köln 1841) and volume 8 (Köln 1842), ZDB-ID 2790481-7: (I.), volume 7, 16 December 1841, p.645, (online), (II.), volume 8, 1 January 1842, p.1, (online) und (III.) Britisches Hoheitsrecht, Jg. 8, 14 February 1842, p.91, (online); Die Kolonie auf der Chatham-Insel, volume 7, 23 December 1841, p.658, (online)

- 1 2 Sieveking, Heinrich [in German] (1896). Delbrück, Hans (ed.). Hamburger Kolonisationspläne 1840–1842. Preußische Jahrbücher. Vol. 86. Berlin: Georg Stilke. pp. 149–170.

- ↑ "The Chatham Islands". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ Masterman, Sylvia (1934). "The Origins of International Rivalry in Samoa: 1845–1884, Chapter ii. The Godeffroy Firm". George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London NZETC. p. 63. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Suamalie N.T. Iosefa; Doug Munro; Niko Besnier (1991). Tala O Niuoku, Te: the German Plantation on Nukulaelae Atoll 1865-1890. Institute of Pacific Studies. ISBN 978-9820200739.

- ↑ John Spurway (23 February 2015). Ma'afu, Prince of Tonga, Chief of Fiji: The life and times of Fiji's first Tui Lau. ANU Press. pp. 665–. ISBN 978-1-925021-18-9.

- ↑ Cord Eberspächer: Die deutsche Yangtse-Patrouille – Deutsche Kanonenbootpolitik in China im Zeitalter des Imperialismus 1900 – 1914, Verlag Dr. Dieter Winkler, Bochum 2004, p.58