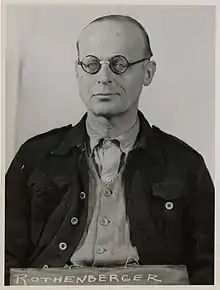

Curt Ferdinand Rothenberger (30 June 1896 in Cuxhaven – 1 September 1959 in Hamburg) was a German jurist and leading figure in the Nazi Party.

Hamburg

In the immediate aftermath of the Nazi seizure of power Rothenberger was part of an unofficial group within the Nazi Party, led by Hans Frank and Roland Freisler, the aim of which was to transform the legal profession by installing loyal party men in leading positions within the judiciary.[1] Rothenberger was appointed Senator of Justice in Hamburg and set about putting these ideas into practice, insisting that all judges had to be "100% national socialist" and had to be trusted by party officials. Where this was not the case the judges faced summary dismissal.[2] Jewish judges were removed from office as early as March 1933 under Rothenberger's orders.[3]

Nonetheless as senior judge in the Hanseatic Higher Regional Court Rothenberger clashed with the Gestapo in 1938 over their practice of rearresting people who had been released from prison. When Rothenberger took the case of two Jehovah's Witnesses who had been arrested immediately following their release after spending eight months in prison for their religious activities it was agreed that the Gestapo would end this practice except in cases where those released were continuing to offend.[4]

Justice Ministry

Rothenberger sent his ideas about judicial reform to prominent legal expert Hans Lammers in early 1941; Lammers was not impressed and rejected the plan. Rothenberger then sent the same ideas to Rudolf Hess, who proved keener but made his ill-fated flight to Scotland before he could act on them. Finally in 1942 Rothenberger condensed his ideas into a short memorandum and, through Martin Bormann, had this version shown directly to Adolf Hitler. Responding favorably, Hitler made a speech to the Reichstag on 26 April 1942 in which he sought to undertake a complete reform of the judiciary based on Rothenberger's proposed principles. The Reichstag, needless to say, immediately approved the requested resolution.[5]

Rothenberger's reform plans sought to give the Nazi Party a closer role in the training of judges.[6] Alongside this he sought to extend the use of lay judges and people's courts at the expense of the professional judiciary at the local level.[7] Nonetheless he argued that the dispensing of justice at the highest levels should remain in the hands of a proper, trained judiciary, an idea that was interpreted by Bormann as not going far enough.[8] Others however saw Rothenberger's ideas as constituting unwarranted attacks on the judiciary. Hans Frank, the President of the Academy for German Law, a body which he had established in 1933, made a series of speeches in June 1942 at several universities defending the status quo as a protest against the Rothernberger proposals. As a result of this controversy, Frank was forced to resign from the presidency on 20 August 1942.[9]

In order to undertake the proposed changes, Justice Minister Franz Schlegelberger was also dismissed in August 1942 and replaced by Otto Thierack, the President of the People's Court since 1936. Rothenberger was appointed his State Secretary in charge of judicial reform. Bormann's ally Herbert Klemm was added as another state secretary in order to limit the power of Rothenberger.[10] In November 1942, Rothenberger was also made Vice-President of the Academy for German Law, which now also was headed by Thierack, who had succeeded Frank.[11]

One of Rothenberger's first acts as state secretary was to make a deal with SS-Gruppenführer Bruno Streckenbach, whereby prisoners deemed as "antisocial" were to be removed from jails and given to the SS, to be worked to death in the Nazi concentration camps.[12] It was arranged with Heinrich Himmler that Jews and Gypsies would join recidivists and those with sentences of eighty years or over in this "antisocial" category.[13]

During an air raid in 1943, four death row inmates managed to escape from Plötzensee Prison. In response, Rothenberger ordered the immediate execution of all current death sentences to "make room". From the nights of 7 September to 12 September 1943, over 250 prisoners were hanged.[14]

Realising that the proposed reforms were causing too much friction at a time when the Second World War was beginning to turn against the Nazis and thus stability was of the essence, Bormann sought to sabotage Rothenberger until finally succeeding in having Thierack dismiss him from his positions in December 1943 on the unusual charge of plagiarism.[15]

Post-war

Rothenberger was one of the defendants at the Judges' Trial, where he was sentenced to seven years in prison.[16] All three state secretaries, Rothenberger, Klemm and Franz Schlegelberger, were charged at the trial.[17] When in 1959 his role during the war was again publicized, Rothenberger committed suicide.[18]

References

- ↑ Dietrich Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2 1933-1945, David & Charles, 1973, p. 46

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 226

- ↑ Frank Bajohr, "Aryanisation" in Hamburg: the economic exclusion of Jews and the confiscation of their property in Nazi Germany, Berghahn Books, 2002, p. 66

- ↑ Detlef Garbe, Between resistance and martyrdom: Jehovah's Witnesses in the Third Reich, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2008, pp. 293-295

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 369

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 372

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 372-373

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 432

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 373

- ↑ CIA, Who's Who in Nazi Germany, p. 84

- ↑ Klee, Ernst (2007). Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt-am-Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. p. 511. ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8.

- ↑ Götz Aly, Peter Chroust, Christian Pross, Cleansing the fatherland: Nazi medicine and racial hygiene, JHU Press, 1994, p. 70

- ↑ Richard Wetzell, Inventing the criminal: a history of German criminology, 1880-1945, UNC Press Books, 2000, p. 288

- ↑ Brigitte Oleschinski: "Gedenkstätte Plötzensee" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2023-02-20. Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand Berlin, S. 57.

- ↑ Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Volume 2, p. 373-374

- ↑ Description of the trial from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ↑ Giles MacDonogh, After the Reich, John Murray, 2007, p. 455

- ↑ Susanne Schott, Curt Rothenberger –eine politische Biographie. Online published doctoral dissertation, Halle, Martin-Luther-Universität , 2001, p. 180 (German).