| Didelphodon Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of Didelphodon skeleton in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Family: | †Stagodontidae |

| Genus: | †Didelphodon Marsh, 1889 |

| Type species | |

| †Didelphodon vorax Marsh, 1889 | |

| Species | |

|

Didelphodon vorax Marsh, 1889 (type) | |

Didelphodon (from Didelph[is] "opossum" plus ὀδών odōn "tooth") is a genus of stagodont metatherians from the Late Cretaceous of North America.[1]

Description

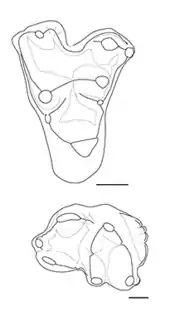

Although perhaps little larger than a Virginia opossum, with a skull length of 12.2 centimetres (4.8 in) and a weight of 5.2 kilograms (11 lb),[2] Didelphodon was the largest Cretaceous mammal.[3] The teeth have specialized bladelike cusps and carnassial notches, indicating that the animal was a predator; the jaws are short and massive and bear enormous, bulbous premolar teeth which appear to have been used for crushing.[4] Analyses of a near-complete skull referred to Didelphodon show that it had an unusually high bite force quotient (i.e. bite force relative to body size) among Mesozoic mammals, suggesting a durophagous diet. However, its skull lacks the vaulted forehead of hyenas and other specialized bone-eating durophagous mammals, indicating that its diet was perhaps a mixture of hard foodstuffs (e.g. snails, bones) alongside small vertebrates and carrion;[2] although omnivorous habits were suggested in the past, it appears that it was incapable of processing plant matter, rendering it more likely to be hypercarnivorous or durophagous.[5] Some convergence with the carnassials of other predatory mammal groups has also been noted.[6]

Discovery

Three species of Didelphodon are known: D. vorax, D. padanicus, and D. coyi. The genus is known from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and the Lance Formation of Wyoming, the Frenchman Formation of Saskatchewan, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, and the Scollard Formation of Alberta, where it is one of the most abundant mammals. It is found solely in late Maastrichtian deposits.[4][1]

Classification

Didelphodon is a stagodontid marsupial related to Eodelphis and Pariadens. The genus appears to descend from the Campanian Eodelphis, and in particular appears to be related to Eodelphis cutleri. Pariadens appears to be more primitive than either Eodelphis or Didelphodon, and is probably sister to their group. Didelphimorphia is an order that was named in 1872 by Gill. Previously, in 1821, Gray named the superfamily Didelphoidea to house the families Alphadontidae, Pediomyidae, Peradectidae, and Stagodontidae, which unites Didelphodon with many other genera.[4]

In 2006, a study found that the stagodontids only contained two taxa, Didelphodon and Eodelphis. The previously-included Pariadens was excluded from the group because its type species, P. kirklandi, lacks any of the clade's characteristics; it was reassigned to Marsupialia incertae sedis. Another species, "P." mckennai lacks marsupial features, and is probably a therian. Another historical stagodontid, Boreodon, is a nomen dubium. Finally, the purported stagodontid Delphodon is probably a synonym of Pediomys or Alphadon.[1]

A 2016 phylogenetic analysis found that Didelphodon and other stagodontids were marsupialiforms. Their relationships within the Marsupialiformes are shown below.[2]

| Marsupialiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Although it has been argued on the basis of the shape of referred tarsal bones that Didelphodon and other stagodontids were semiaquatic due to having flexible feet, these traits may in fact be evidence of increased rigidity in the foot.[1][4] Nevertheless, a recently-found and as-of-yet undescribed specimen, located just 40 m (130 ft) away from a Triceratops in a riverbed, suggests that Didelphodon may have possessed an otter-like body with a tasmanian devil-like skull. A study that is being prepared by Kraig Derstler, Greg Wilson, Robert Bakker, Ray Vodden and Mike Triebold will describe this new specimen, housed in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center.[7] A study on Mesozoic mammal locomotion demonstrates that Didelphodon groups with semi-aquatic species.[8]

The evolution of Didelphodon and other large stagodontids (as well as large deltatheroideans like Nanocuris) occurs after the local extinction of eutriconodont mammals, suggesting passive or direct ecological replacement.[9] Given that all insectivorous and carnivorous mammal groups suffered heavy losses during the mid-Cretaceous, it seems likely these metatherians simply occupied niches left after the extinction of eutriconodonts.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fox, R.C.; Naylor, B.G. (2006). "Stagodontid marsupials from the Late Cretaceous of Canada and their systematic and functional implications" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (6): 13–36.

- 1 2 3 Wilson, G.P.; Ekdale, E.G.; Hoganson, J.W.; Calede, J.J.; Linden, A.V. (2016). "A large carnivorous mammal from the Late Cretaceous and the North American origin of marsupials". Nature Communications. 7: 13734. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713734W. doi:10.1038/ncomms13734. PMC 5155139. PMID 27929063.

- ↑ Rose 2006, p. 78

- 1 2 3 4 Kielan-Jaworowska, Z.; Cifelli, R.L.; Cifelli, R; Luo, Z.X. (2004). Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution and Structure. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 441–462. ISBN 9780231509275.

- ↑ Leonardo M. Carneiro; Édison Vicente de Oliveira (2017). "Systematic affinities of the extinct metatherian Eobrasilia coutoi Simpson, 1947, a South American Early Eocene Stagodontidae: implications for "Eobrasiliinae"". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 20 (3): 355–372. doi:10.4072/rbp.2017.3.07.

- ↑ de Muizon, C.; Lange-Badre, B. (1997). "Carnivorous dental adaptations in tribosphenic mammals and phylogenetic reconstruction". Lethaia. 30 (4): 353–366. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1997.tb00481.x.

- ↑ "Didelphodon vorax". Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center. 2010-12-07. Archived from the original on 2013-12-12. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ↑ Meng Chen, Gregory Philip Wilson, A multivariate approach to infer locomotor modes in Mesozoic mammals, Article in Paleobiology 41(02) · February 2015 doi:10.1017/pab.2014.14

- ↑ G. W. Rougier, B. M. Davis, and M. J. Novacek. 2015. A deltatheroidan mammal from the Upper Cretaceous Baynshiree Formation, eastern Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 52:167-177

- ↑ David M. Grossnickle, P. David Polly, Mammal disparity decreases during the Cretaceous angiosperm radiation, Published 2 October 2013.doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2110

Further reading

- Rose, Kenneth David (2006). The beginning of the age of mammals. Baltimore: JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801884726.

- Clemens, W. A., Jr. (1979). Marsupialia. Mesozoic mammals: the first two-thirds of mammalian history. J. A. Lilligraven, Kielan-Jaworowska and W. A. Clemens, Jr. Berkeley, University of California Press: 192–220.

- Fox, R. C., & Naylor, B. G. (1986). A new species of Didelphodon Marsh (Marsupialia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada: paleobiology and phylogeny. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 172, 357–380.

- BBC Online: Science & Nature: Prehistoric Life