| Peradectes Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Full skeleton of Peradectes from the Naturmuseum Senckenberg. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Family: | †Peradectidae |

| Genus: | †Peradectes Matthew and Granger, 1921 |

Peradectes is an extinct genus of small metatherian mammals known from the latest Cretaceous[1] to Eocene of North and South America and Europe.[2] The first discovered fossil of P. elegans, was one of 15 Peradectes specimens described in 1921 from the Mason pocket fossil beds in Colorado.[3] The monophyly of the genus has been questioned.[4]

Etymology

The genus name is derived from the Greek for “pouch” (pera-) and “biter” (-dectes), indicating a marsupial thought to engage primarily in carnivory.[3]

Taxonomy and relationships

The exact placement of Peradectes and its relationships have been uncertain. Some definitions of the group may be polyphyletic, and the extinct genus Thylacodon was thought by some to be synonymous with Peradectes; however, the two are now considered separate genera.[4]

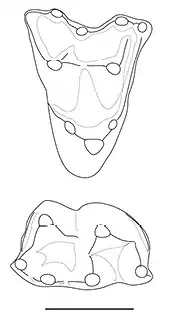

It is known to be a metatherian and further a member of the crown clade Marsupialia along with other extinct and extant groups due to distinct marsupial dentition and jaw anatomy.[5] Once thought to be a member of Didelphidae along with modern opossums,[3][6] it is now classified within a separate family, Peradectidae, due in part to the predilambdodont, rather than true dilambdodont, upper molars.[4][7][8] Some classifications recognize a subfamily within Peradectidae, Peradectinae, which includes at least Peradectes, Thylacodon, and Nanodelphys.[1][9]

Though no longer believed to be didelphids, the opossum-like Peradectes and its relatives in Peradectidae may represent a primitive step in the evolution of opossums. A “peradectid or peradectid-like ancestor” may have given rise to didelphids in the Cretaceous.[10]

Description

As with other mammals, due to the hardness of the enamel, teeth and jaws make up much of the fossil record of Peradectes. The jaw of the type specimen P. elegans is slender with a medially inflected angle as in other marsupials like opossums, and it possesses simple premolars and comparatively large canine teeth.[3] Peradectes upper molars are distinctive, noted to have a larger metacone than protocone, a buccally oriented stylar shelf with cusp B as the largest cusp, and a short postmetaconule crista.[11] Some specimens are also described as having a robust skull with a short snout and vertical directed lower incisors.[12]

Peradectes fossils tend to be small, with individual teeth for example measuring no larger than 1.5 mm.[9] One particular specimen assigned to Peradectes has postcranial anatomy common to modern arboreal marsupials, including reduced transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae, a posterior anticlinal vertebra, somewhat short metatarsals, and a comparatively long tail (1.5-2 times the length of the head and body) thought to have been prehensile.[12]

Distribution

Fossils of the group Peradectidae, of which Peradectes is a part, have been found primarily in the Northern Hemisphere.[8] It may be the only marsupial genus known from the Tiffanian North American land mammal age in the Paleocene, retaining its wide-ranging distribution from the preceding Torrejonian age.[1]

Specimens have been found at the Messel site of Germany[12] and other parts of that country and southern England.[2] Though peradectids were most common in the northern continents, specimens assigned to Peradectes are also known from South America.[1][10] The existence of Peradectes in South America is significant in terms of broader marsupial evolution, as there is evidence that ancestors of modern Australian marsupials diverged from the lineage leading to modern New World marsupials on that continent.[13]

Palaeoecology

The skeletal anatomy of Peradectes is consistent with at least a partially arboreal lifestyle.[12] Analyses have also suggested a partially scansorial life mode (climbing but not necessarily living in trees) for at least some Peradectes species, along with frugivorous or insectivorous feeding.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Korth, W. W. (2008). Marsupialia. In C. M. Janis, G. F. Gunnell, & M. D. Uhen (Eds.), Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America: Volume 2, Small Mammals, Xenarthrans, and Marine Mammals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 Czaplewski, J. J. (Ed.). (n.d.). Paleobiology Database Navigator. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Matthew, W., & Granger, W. (1921). New genera of Paleocene mammals (American Museum novitates ; no. 13). New York City: By order of the Trustees of The American Museum of Natural History.

- 1 2 3 Williamson, T.E., Brusatte, S.L., Carr, T.D., Weil, A. & Standhardt, B.R. (2012) The phylogeny and evolution of Cretaceous–Palaeogene metatherians: cladistic analysis and description of new early Palaeocene specimens from the Nacimiento Formation, New Mexico, Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 10:4, 625-651.

- ↑ Wilson, G. P., Ekdale, E. G., Hoganson, J. W., Calede, J. J., & Vander Linden, A. (2016). A large carnivorous mammal from the Late Cretaceous and the North American origin of marsupials. Nature communications, 7, 13734.

- ↑ McKenna, M.C. & Bell, S.K. (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level 1-640. Information accessed from Paleobiology Database. (n.d.). Peradectes. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ↑ Johanson, Z. (1996). New Marsupial from the Fort Union Formation, Swain Quarry, Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology, 70(6), 1023-1031.

- 1 2 Horovitz, I., Bloch, Martin, J., Ladevèze, S., Kurz, C. and Sánchez-Villagra M.R. (2009). Cranial anatomy of the earliest marsupials and the origin of opossums. PLoS One 4(12):e8278.

- 1 2 Korth, W. (1994). Middle Tertiary Marsupials (Mammalia) from North America. Journal of Paleontology, 68(2), 376-397.

- 1 2 Marshall, L.G. & de Muizon, C. (1988). The dawn of the Age of Mammals in South America. National Geographic Research, 4(1):23-55.

- ↑ Williamson, T.E. & Lofgren, D.L. (2014). "Late Paleocene (Tiffanian) Metatherians from the Goler Formation, California," Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 34(2), 477-482. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2013.804413.

- 1 2 3 4 Rose, K.D (2012). The importance of Messel for interpreting Eocene Holarctic mammalian faunas. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 92, 631–647.

- ↑ Nilsson, M. A., Churakov, G., Sommer, M., Tran, N. V., Zemann, A., Brosius, J., & Schmitz, J. (2010). Tracking marsupial evolution using archaic genomic retroposon insertions. PLoS biology, 8(7), e1000436.

- ↑ Kurz, C. (2005). Ecomorphology of opossum-like marsupials from the Tertiary of Europe and a comparison with selected taxa. Kaupia, 14, 21-26.