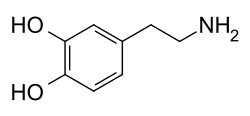

Dopaminergic means "related to dopamine" (literally, "working on dopamine"), dopamine being a common neurotransmitter.[1] Dopaminergic substances or actions increase dopamine-related activity in the brain. Dopaminergic brain pathways facilitate dopamine-related activity. For example, certain proteins such as the dopamine transporter (DAT), vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), and dopamine receptors can be classified as dopaminergic, and neurons that synthesize or contain dopamine and synapses with dopamine receptors in them may also be labeled as dopaminergic. Enzymes that regulate the biosynthesis or metabolism of dopamine such as aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase or DOPA decarboxylase, monoamine oxidase (MAO), and catechol O-methyl transferase (COMT) may be referred to as dopaminergic as well. Also, any endogenous or exogenous chemical substance that acts to affect dopamine receptors or dopamine release through indirect actions (for example, on neurons that synapse onto neurons that release dopamine or express dopamine receptors) can also be said to have dopaminergic effects, two prominent examples being opioids, which enhance dopamine release indirectly in the reward pathways, and some substituted amphetamines, which enhance dopamine release directly by binding to and inhibiting VMAT2.

Supplements and drugs

The following are examples of dopaminergic substances:

Precursors

- Dopamine precursors including L-phenylalanine and L-tyrosine are used as dietary supplements. L-DOPA (Levodopa), another precursor, is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

Receptor agonists

- Dopamine receptor agonists such as apomorphine, bromocriptine, cabergoline, dihydrexidine (LS-186,899), dopamine, fenoldopam, piribedil, lisuride, pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine, are used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and to treat depression and anxiety.

Receptor antagonists/receptor blockers

- Dopamine receptor antagonists including typical antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine (Thorazine), fluphenazine, haloperidol (Haldol), loxapine, molindone, perphenazine, pimozide, thioridazine, thiothixene, and trifluoperazine, the atypical antipsychotics such as amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), sulpiride, and ziprasidone, and antiemetics like domperidone, metoclopramide, and prochlorperazine, among others, which are used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as antipsychotics, and nausea and vomiting.

Reuptake inhibitors/transporter blockers

- Dopamine reuptake inhibitors (DRIs) or dopamine transporter (DAT) inhibitors such as methylphenidate (Ritalin), amineptine, and nomifensine, cocaine, methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV; "Sonic"), ketamine, and phencyclidine (PCP), among others, which are used in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy as psychostimulants, obesity as anorectics, depression and anxiety as antidepressants and anxiolytics, respectively, drug addiction as anticraving agents, and sexual dysfunction, as well as illicit street drugs.

- Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors such as reserpine, tetrabenazine, and deserpidine, which are used as sympatholytics or antihypertensives, and in the past as antipsychotics.

Releasing agents

- Dopamine releasing agents (DRAs) such as phenethylamine, amphetamine, lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse), methamphetamine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), phenmetrazine, pemoline, 4-methylaminorex (4-MAR), and benzylpiperazine, among many others, which, like DRIs, are used in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy as psychostimulants, obesity as anorectics, depression and anxiety as antidepressants and anxiolytics respectively, drug addiction as anticraving agents, and sexual dysfunction as aphrodisiacs. Many of these compounds are also illicit street drugs.

"Activity enhancers"

- Dopamine "activity enhancers" such as BPAP and PPAP, which are currently only research chemicals, but are being investigated for clinical development in the treatment of a number of medical disorders. To date, only phenylethylamine and tryptamine have been identified as endogenous "activity enhancers".[2]

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors (MAOIs) including nonselective agents such as phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and isocarboxazid, MAOA selective agents like moclobemide, and MAOB selective agents such as selegiline, rasagiline, and pargyline, as well as the harmala alkaloids like harmine, harmaline, tetrahydroharmine, harmalol, harman, and norharman, which are found to varying degrees in Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco), Banisteriopsis caapi (ayahuasca, yage), Peganum harmala (Harmal, Syrian Rue), Passiflora incarnata (Passion Flower), and Tribulus terrestris, among others, which are used in the treatment of depression and anxiety as antidepressants and anxiolytics, respectively, in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and dementia, and for the recreational purpose of boosting the effects of certain drugs like phenethylamine (PEA) and psychedelics like dimethyltryptamine (DMT) via inhibiting their metabolism.

Dopamine synthesis enhancers

Other enzyme inhibitors

- Catechol O-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitors such as entacapone and tolcapone, which are used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

- Dopamine β-hydroxylase inhibitors like disulfiram (Antabuse), which can be used in the treatment of addiction to cocaine and similar dopaminergic drugs as a deterrent drug. The excess dopamine resulting from inhibition of the dopamine β-hydroxylase enzyme increases unpleasant symptoms such as anxiety, higher blood pressure, and restlessness. Disulfiram is not an anticraving agent, because it does not decrease craving for drugs. Instead, positive punishment from its unpleasant effects deters drug consumption.[6]

- Phenylalanine hydroxylase inhibitors like 3,4-dihydroxystyrene), which is currently only a research chemical with no suitable therapeutic indications, likely because such drugs would induce the potentially highly dangerous hyperphenylalaninemia or phenylketonuria.

- Tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitors like metirosine, which is used in the treatment of pheochromocytoma as a sympatholytic or antihypertensive agent.

- Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase or DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors including benserazide, carbidopa, and methyldopa, which are used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease in augmentation of L-DOPA to block the peripheral conversion of dopamine, thereby inhibiting undesirable side-effects, and as sympatholytic or antihypertensive agents.

- Others such as hyperforin and adhyperforin (both found in Hypericum perforatum St. John's Wort), L-theanine (found in Camellia sinensis, the tea plant), and S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe)

See also

References

- ↑ Melinosky C (27 November 2022). "Parkinson's Disease: Glossary of Terms". WebMD.

- ↑ Shimazu S, Miklya I (May 2004). "Pharmacological studies with endogenous enhancer substances: beta-phenylethylamine, tryptamine, and their synthetic derivatives". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 28 (3): 421–427. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.016. PMID 15093948. S2CID 37564231.

- ↑ Rangasamy SB, Dasarathi S, Pahan P, Jana M, Pahan K (June 2019). "Low-Dose Aspirin Upregulates Tyrosine Hydroxylase and Increases Dopamine Production in Dopaminergic Neurons: Implications for Parkinson's Disease". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 14 (2): 173–187. doi:10.1007/s11481-018-9808-3. PMC 6401361. PMID 30187283.

- ↑ Mikhaylova M, Vakhitova JV, Yamidanov RS, Salimgareeva MK, Seredenin SB, Behnisch T (October 2007). "The effects of ladasten on dopaminergic neurotransmission and hippocampal synaptic plasticity in rats". Neuropharmacology. 53 (5): 601–608. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.001. PMID 17854844. S2CID 43661752.

- ↑ Voznesenskaia TG, Fokina NM, Iakhno NN (2010). "[Treatment of asthenic disorders in patients with psychoautonomic syndrome: results of a multicenter study on efficacy and safety of ladasten]". Zhurnal Nevrologii I Psikhiatrii Imeni S.S. Korsakova. 110 (5 Pt 1): 17–26. PMID 21322821.

- ↑ Krampe H, Stawicki S, Wagner T, Bartels C, Aust C, Rüther E, Poser W, Ehrenreich H (January 2006). "Follow-up of 180 alcoholic patients for up to 7 years after outpatient treatment: impact of alcohol deterrents on outcome". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 30 (1): 86–95. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00013.x. PMID 16433735.