Douglas Young | |

|---|---|

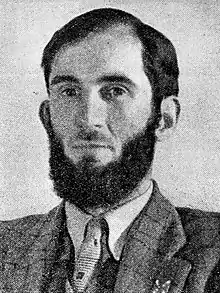

Young, c. 1945 | |

| Leader of the Scottish National Party | |

| In office 30 May 1942 – 9 June 1945 | |

| Preceded by | William Power |

| Succeeded by | Bruce Watson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 June 1913 Tayport, Fife, Scotland |

| Died | 23 October 1973 (aged 60) Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States |

| Political party | Scottish National Party |

| Other political affiliations | Labour Party |

| Spouse | Helena Auchterlonie (m. 1943–1973) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | University of St Andrews University of Oxford |

| Profession | Lecturer, Professor (Classics) |

Douglas Cuthbert Colquhoun Young (5 June 1913 – 23 October 1973) was a Scottish poet, scholar, translator and politician. He was the leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP) 1942-1945, and was a classics professor at McMaster University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Early life and education

Young was born in Tayport, Fife, the son of Stephen Young; a mercantile clerk employed in India by a Dundee jute firm. Young senior had insisted that his pregnant wife return home to give birth to their son in Scotland. However, shortly after his birth in Fife, Douglas was taken to India with his mother, where he spent the early part of his childhood in Bengal, speaking Urdu as a second language there.[1]

From the age of eight, Young attended Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh, where he developed a deep interest in History and the Classics. He studied at the University of St Andrews, graduating with a first-class MA in Classics in 1934, and then at New College, Oxford, 1935-1938.[1] Standing at 6 feet and 7 inches (200 cm) tall, he also possessed a large range of talents over a wide array of subjects and was recognised as a polymath.[2][3]

Classicist

Young began his professional academic career at the University of Aberdeen, where he served as assistant lecturer in Greek from 1938 to 1941.

Following the war, Young was lecturer in Latin at University College, Dundee (which was then a part of the University of St Andrews), from 1947 to 1953, then lecturer in Greek at the University of St Andrews from 1953 to 1968.[1]

He translated the comedy The Birds by Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. The Burdies was first performed in 1959 in Edinburgh.[2][3] In 1966 it was performed by the Royal Lyceum Company.[3][4][5]

In 1952, Young travelled with Naomi Mitchison as part of an Authors' World Peace Appeal delegation to the Soviet Union. Here Young met several Russian authors, including Mikhail Zoshchenko and Samuil Marshak.[6] During the visit, the Soviet authorities "refused to transmit a radio script" where Young stated the Western European view of the Korean War.[6] Young served as president of Scottish PEN from 1958 to 1962.

In 1968, he moved to Canada to a post as professor of classics at McMaster University, where he taught until 1970. He was then the first Paddison Professor of Greek at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1970 until his death.[1][2][7]

Political career

SNP during World War II

Already a member of the Labour Party, Young joined the Scottish National Party (SNP) in 1938, serving as Chair of the SNP in Aberdeen during the 1940s. The SNP was pledged to oppose conscription, except by a Scottish government, and Young refused to register either for military service or as a conscientious objector during World War II. He served two terms in prison, reading Greek as much as possible in his cell. At trial, Young contested the authority of the British government, specifically whether the Act of Union could be used to compel Scots to serve in the British military outside the British Isles.[8] He was convicted under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 at the Glasgow Sheriff Court in April 1942.[9] He appealed at the High Court in July 1942 but this was dismissed.[9] Young's activities were popularly vilified as undermining the British war effort against the Nazis. His daughter later claimed that he had volunteered in 1939, and was unfit due to a heart problem.[10]

Of his first prison term, served in Saughton, Young wrote:

On weekdays I used to work about the grounds in what was called 'the garden party' and on Sundays I played a wheezy old harmonium for the Presbyterian services in the chapel.

Dr. Robert McIntyre, secretary of the SNP, organised a procession complete with bagpipes to serenade Young on Sundays at the prison-gates.

Shortly after his release from prison, Young stood as the SNP candidate at the Kirkcaldy Burghs by-election in February 1944. His election agent was Arthur Donaldson and the campaign owed much to the input of Dr. Robert McIntyre. In a three-way contest, Young polled 6,621 votes, 42% of the poll, securing a strong second place to the successful Coalition Labour candidate Thomas Hubbard.[11]

In June 1944, he appeared at Paisley Sheriff Court charged with not complying with Defence Regulations and was sentenced to a second term in prison.[12] In October, his appeal was heard at the Court of Criminal Appeal but dismissed by Lord Cooper.[13]

Post-war

Young resigned from the SNP in 1948, in protest against the party's new constitution, which prohibited being a member of the SNP while also being a member of another political party. He had been a member of both the Labour Party and the SNP until he was elected leader in 1942, and had argued against efforts to ban dual-party membership when this was proposed over the next few years leading up to the passing of the new constitution.[14] The event which brought the situation to a head was the party's expulsion of Robert Wilkie, who had run as an "Independent Nationalist" under the SNP ticket at the 1948 Glasgow Camlachie by-election.[15] Young rejoined the Labour Party in June 1951, partly because of the perilous situation the party found itself in with its small parliamentary majority following the 1950 general election. He also felt that the response to the Scottish Covenant was certain to bring about the establishment of a Scottish Parliament, which he had supported as a Labour Party member.[16]

In 1967, he was a founder member of the 1320 Club, which sought to provide a nationalist alternative to the SNP.[1]

Later life and death

Young died unexpectedly at his desk in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, on 23 October 1973, aged 60.[7] He was married in 1943 to the Scottish ceramic artist Helena (Hella) Auchterlonie (1910–1999); the couple had two daughters.[17]

In 2003, a plaque to commemorate him was unveiled at the Writers' Museum in Edinburgh.[18]

Publications

- Quislings in Scotland: Review of the Fifth Column, 1942

- Auntran Blads, 1943

- A Braird o Thristles, 1947

- Chasing an Ancient Greek, 1950

- Scottish Verse, 1851–1951, 1952

- The Puddocks, 1957

- The Burdies, 1959

- Theognis, 1961

- Edinburgh in the age of Sir Walter Scott, 1965

- Hippolytus, 1968

- St. Andrews: Town and Gown, Royal and Ancient, 1969

- Scotland, 1971

- Oresteia, 1974

- Naething Dauntit. The Collected Poems of Douglas Young, Edited by Emma Dymock, with a Foreword by Clara Young. humming earth, Edinburgh, 2016.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Derick S. Thomson, Young, Douglas Cuthbert Colquhoun (1913–1973), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 "Douglas Young, poet and nationalist". The Glasgow Herald. 27 October 1973. p. 7. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Findlay, Bill (2005). "Towards a reassessment of Douglas Young. Motivation and his Aristophanic translations". Études Écossaises (10): 175–186. doi:10.4000/etudesecossaises.161.

- ↑ "Scotland and the Arts". The Glasgow Herald. 22 August 1966. p. 8. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ ""Burdies" Strictly for Scots?". The Glasgow Herald. 24 August 1966. p. 10. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Soviet Bans Scots Poet's Peace Talk", Evening Times, 30 October 1952, p. 2.

- 1 2 "About Us: Departmental History: Douglas C.C. Young". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ Baker, Gregory (25 July 2016). 15 "Attic Salt into an Undiluted Scots": Aristophanes and the Modernism of Douglas Young. Brill. pp. 307–330. doi:10.1163/9789004324657_016. ISBN 9789004324657. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Scots Nationalist Chairman. Appeal "Incompetent and Irrelevant"". The Herald. 10 July 1942. p. 5. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ Young, Clara. "SNP's Young 'no conscientious objector'". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ "The By-Elections. Light Poll at Kirkcaldy". The Glasgow Herald. 18 February 1944. p. 2. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ "Lochwinnoch Man Sent to Prison". The Glasgow Herald. 13 June 1944. p. 4. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Douglas Young's Appeal Fails. 1942 Case Recalled". The Glasgow Herald. 7 October 1944. p. 5. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish Nationalist Leaves Party". The Glasgow Herald. 17 November 1948. p. 6. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. Acc. 10090, Papers of Dr Robert Douglas McIntyre, MB ChB, DPH, Duniv, JP. File 15: Correspondence and papers of or concerning Douglas Young. 11 December 1947 letter from Young to McIntyre; 16 April 1948 letter from Young to Jock Mackie. Accessed 16 July 2015.

- ↑ 'Mr Douglas Young Rejoins Labour', The Glasgow Herald, 26 June 1951, p. 5.

- ↑ Dillon, Lorna (12 October 1999). "Obituary, Hella Young". The Herald. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish Writers' Museum pays tribute to three 20th century poets". The Scotsman. 27 September 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2018.