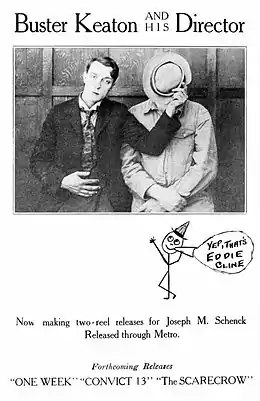

Edward F. Cline | |

|---|---|

Motion Picture News, 1920 | |

| Born | Edward Francis Cline November 4, 1891 Kenosha, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | May 22, 1961 (aged 69) Hollywood, California, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, screenwriter, actor |

Edward Francis Cline (November 4, 1891 – May 22, 1961) was an American screenwriter, actor, writer and director best known for his work with comedians W.C. Fields and Buster Keaton. He was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin and died in Hollywood, California.

Career

Cline began working for Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios in 1914 and supported Charlie Chaplin in some of the shorts he made at the studio. At one time he claimed credit for having come up with the idea for the Sennett Bathing Beauties.[1] When Buster Keaton began making his own shorts, after having worked with Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle for years, he hired Cline as his co-director.[2] In Keaton's short films Cline and Keaton himself were the only two regular gag men.[3] For Keaton's 1921 short Hard Luck, Cline is credited with originating Keaton's personal favorite gag from his films. At the end of the film, Keaton dives into a swimming pool which has been emptied of water. Years later, he emerges from the hole which his fall created, accompanied by a Chinese wife and two small Chinese-American children.[4] Besides working on most of Keaton's early shorts, Cline co-directed Keaton's first feature, Three Ages (1923).[1]

Although he worked mostly in comedy, Cline directed some melodramas and the musical Leathernecking (1930), Irene Dunne's film debut.[1]

Cline began his association with W.C. Fields in the 1932 Paramount film Million Dollar Legs. The film had several veterans of Mack Sennett's Keystone films, including Andy Clyde, Ben Turpin, and Hank Mann. Producer Herman J. Mankiewicz recalled of Cline, "He was very much of the old, old comedy school. He didn't know what was happening in Million Dollar Legs. At all. But he enjoyed doing it, because he had Andy Clyde. And Ben Turpin. And Bill Fields."[5]

During troubles with the shooting of Fields's 1939 film You Can't Cheat an Honest Man, largely resulting from Fields's clashes with director George Marshall, Fields managed to put Cline in the director's chair. Co-star Constance Moore remembered "Before Mr. Fields did the famous Ping-Pong scene he wanted Mr. Cline. He said 'I've worked with Cline. He knows my work.' He first put out his feelers. Then he started asking for Cline. Then he demanded him..."[6] Cline's work on the film lasted 10 days during which he shot the party scene containing the ping pong game.[7]

As director of My Little Chickadee (1940), Cline's desire that the actors follow the script caused some difficulties with Fields until Cline finally submitted to Fields's tendency to ad-lib. Cline objected to the ad-libbing because it caused the crew to laugh, and Cline's own laughter necessitated a quick cut at the end of one of Fields's barroom scenes.[8]

Cline directed Fields's last two starring films, The Bank Dick (1940) and Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941). Recalling their work together, Cline said that Fields chose him to direct his films because he was the only person in Hollywood who knew "less about making movies" than Fields himself.[8] Assistant director Edward Montagne remembered, "Fields and Cline were basically the same type. They both had great comedy sense... With actors, if he thought they were on the right track, he'd let them go."[8]

Universal Pictures, which had hired Cline to direct Fields, released Fields in 1941 but retained Cline, signing him to a new contract. Cline directed many of the studio's musical comedies, starring Gloria Jean, The Ritz Brothers, and Olsen and Johnson. He was dismissed, along with other directors, producers, and actors, when new owners took over the studio in 1945. Cline moved over to Monogram Pictures, directing and/or writing the studio's "Jiggs and Maggie" comedies. The last one, in 1950, was co-directed by veteran William Beaudine.

Television

Cline became a pioneer in television when his old crony, Buster Keaton, became one of the first movie comedians to succeed in the new medium. Keaton and Cline collaborated on two of Keaton's series.

Comic bandleader Spike Jones was famous for using wild visual gags in his band's performances, and his television show required even more material. Jones found an ideal resource in Eddie Cline, whose knack for comedy (and long memory for old sight gags) made him a valuable assistant. Cline remained in Jones's employ well into the 1950s.

Personal life

In 1913, Cline became engaged to Minnie Elizabeth Matheis, aged 18, who previously had been engaged three times in three months.[9] They married on March 6, 1916.[10] In 1918, they had a daughter, named Elizabeth Normand; Minnie contracted an infection in childbirth and died four days later.[11]

In 1919, Cline married Beatrice Altman. They had no children.[11] She died in 1949.[12]

Cline died of cirrhosis in 1961.[12]

Partial filmography

Cline is credited as director unless noted. He directed nearly 60 Mack Sennett comedies between 1914 and 1933.[13]

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 | The Rounders | Short film; actor only[14] |

| 1916 | His Bread and Butter | Short film[14] |

| 1920 | One Week | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1920 | Convict 13 | Short film; also screenwriter, actor[14] |

| 1920 | Neighbors | Short film; also screenwriter and actor[14] |

| 1920 | The Scarecrow | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1921 | The Haunted House | Short film; also screenwriter and actor[14] |

| 1921 | Hard Luck | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1921 | The High Sign | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1921 | The Goat | Short film; actor only[14] |

| 1921 | The Playhouse | Short film; also screenwriter[14] and actor |

| 1921 | The Boat | Short film; also screenwriter and actor[14] |

| 1922 | The Paleface | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1922 | Cops | Short film; also screenwriter and actor[14] |

| 1922 | My Wife's Relations | Short film; also screenwriter and actor[14] |

| 1922 | The Frozen North | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1922 | The Electric House | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1922 | Daydreams | Short film; also screenwriter and actor[14] |

| 1923 | The Balloonatic | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1923 | The Love Nest | Short film; also screenwriter[14] |

| 1923 | Circus Days | [15] |

| 1923 | Three Ages | Co-director (with Buster Keaton)[15] |

| 1923 | The Meanest Man in the World | [15] |

| 1924 | Along Came Ruth | [15] |

| 1924 | Little Robinson Crusoe | [15] |

| 1924 | Captain January | [15] |

| 1925 | The Rag Man | [15] |

| 1925 | Old Clothes | [15] |

| 1926 | Flirty Four-Flushers | |

| 1927 | Let It Rain | [15] |

| 1927 | Soft Cushions | [15] |

| 1929 | The Forward Pass | [15] |

| 1930 | Hook, Line and Sinker | [15] |

| 1930 | Leathernecking | [15] |

| 1931 | Cracked Nuts | [15] |

| 1932 | Million Dollar Legs | [15] |

| 1934 | The Dude Ranger | [15] |

| 1934 | Peck's Bad Boy | [15] |

| 1935 | When a Man's a Man | [15] |

| 1935 | It's A Great Life | |

| 1937 | Forty Naughty Girls | |

| 1939 | You Can't Cheat an Honest Man | [15] |

| 1940 | My Little Chickadee | [15] |

| 1940 | The Bank Dick | [15] |

| 1941 | Never Give a Sucker an Even Break | [15] |

| 1942 | Give Out, Sisters | [15] |

| 1942 | What's Cookin'? | [15] |

| 1942 | Behind the Eight Ball | [15] |

| 1943 | Crazy House | [15] |

| 1944 | Hat Check Honey | [15] |

| 1944 | Ghost Catchers | [15] |

| 1945 | Penthouse Rhythm | [15] |

| 1946 | Bringing up Father | [15] |

| 1947 | Jiggs and Maggie in Society | Also screenwriter[15] |

| 1947 | Jiggs and Maggie in Court | Also screenwriter[15] |

| 1949 | Jiggs and Maggie in Jackpot Jitters | Screenwriter only[15] |

| 1950 | Jiggs and Maggie Out West | Co-director (with William Beaudine) and screenwriter[15] |

References

- 1 2 3 Curtis, James (2003). W.C. Fields: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 405. ISBN 0-06-017337-8.

- ↑ Meade, Marion (1995). Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase. New York: Harper Collins. p. 93. ISBN 0-06-017337-8.

- ↑ Meade, p. 134.

- ↑ Meade, p. 104.

- ↑ Curtis, p. 241.

- ↑ Curtis, pp. 384-385.

- ↑ Curtis, pp. 386-387.

- 1 2 3 Curtis, p. 407.

- ↑ "Wed Early Next Month". Los Angeles Times. February 13, 1916. p. 40.

- ↑ "Love Marathon Keeps Sorority on Tiptoe". Los Angeles Times. June 2, 1913. p. 11.

- 1 2 Foote, Lisle (2014). Buster Keaton's Crew. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 64.

- 1 2 Foote, Lisle (2014). Buster Keaton's Crew. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 72.

- ↑ Walker, Brent E. (2010). Mack Sennett's Fun Factory. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-7864-7711-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Eddie Cline". BFI Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 "Edward F. Cline". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

Further reading

- Jordan R. Young (2005). Spike Jones Off the Record: The Man Who Murdered Music (3rd edition). Albany: BearManor Media. ISBN 1-59393-012-7.

- Scott MacGillivray and Jan MacGillivray (2005). Gloria Jean: A Little Bit of Heaven. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0595674541.

- Lisle Foote (2014). Buster Keaton's Crew: The Team Behind His Silent Films Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.. ISBN 9-780786-496839.

External links

Media related to Edward F. Cline at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Edward F. Cline at Wikimedia Commons Works by or about Edward Francis Cline at Wikisource

Works by or about Edward Francis Cline at Wikisource- Works by or about Edward F. Cline at Internet Archive

- Edward F. Cline at IMDb