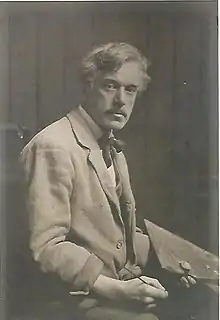

Edward Stott | |

|---|---|

Edward Stott c. 1890 | |

| Born | William Edward Stott 25 April 1855 Rochdale, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 19 March 1918 (aged 62) Amberley, West Sussex, England |

| Education | Manchester Academy of Fine Art, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts |

| Known for | Oil painting, Watercolour |

| Movement | Naturalism, Barbizon School, New English Art Club |

| Awards | Associate Royal Academy |

Edward Stott ARA (24 April 1855 – 19 March 1918) was an English painter of the late Victorian to early twentieth century period. He trained in Paris under Carolus Duran and was strongly influenced by the Rustic Naturalism of Bastien-Lepage and the work of the Impressionists, which he married with the English landscape tradition of John Linnell and Samuel Palmer. In the mid-1880s he settled in rural Sussex where he was the central figure in an artistic colony. His forté was painting scenes of domestic and working rural life and the surrounding landscapes often depicted in fading light. Stott's work achieved critical and commercial success at home and in Europe in his lifetime but his style of painting became unfashionable in the aftermath of the Great War and much of his work is now neglected and unconsidered.[1][note 1][note 2]

Early life

.jpg.webp)

William Edward Stott was born in Wardleworth, now a contiguous part of Rochdale in Lancashire to Samuel and Jane Stott (née Pilling). His father was a prosperous businessman and owner of a cotton mill in Rochdale who served the town as Mayor from 1863 to 1864 and again during 1865–1866 under a Liberal banner. These were painful years for the cotton industry in Lancashire as the effects of overproduction in the late fifties were exacerbated in 1861 by a major interruption in the cotton supply caused by the start of the American Civil War. The result was unemployment and famine in the mill towns of Lancashire and a period of deprivation known as the Lancashire Cotton Famine.[2]

Whilst Stott Snr must have been impacted financially and it is known he diversified into the owning of coal mines, he was nevertheless able to provide a young Edward Stott with a private education, first at Rochdale Grammar School and latterly at King's Ely where he boarded. He appears to have been studious and artistic but also diffident, sensitive and melancholic judging from an early self-portrait.[3] It became apparent that he would be unsuited to taking over the family business, despite the obvious wish of his strong-minded father and after five years working at various jobs in his father's Manchester office whilst simultaneously attending art classes part-time at the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts, Stott opted on a change of career.

In 1880 Stott determined to become a full-time artist and with the support of an unknown benefactor he moved to Paris and to the atelier of Charles August Carolus- Duran.[4] This was a well-trodden path used by some British and Irish art students of the period. It was often seen as a staging post into the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts at which Stott studied under Alexandre Cabanel. Although Cabanel generally painted classical and religious subjects in an academic style, which were dismissed derisively as L'art pompier (literally ‘Fireman art’) by some critics,[5] he was a portrait painter of skill with a deep knowledge of French art of the nineteenth century.[6] Stott was thus exposed to influences such as Realism as typified by Jules Bastien Lepage, the impressionists, and the earlier influences of the Barbizon School and in particular Corot and Millet, from whom Stott incorporates some of the prominent features in the use of colour, softness of form and in tonal qualities.[7] During his period of training in Paris, Stott exhibited four paintings at Paris Salon: The Helping Hand of a Small Friend, (1882) and Solitude (1883) exhibited in 1883 whilst The High Grasses (1883) and The Return to the Poultry House (1884) were shown the following year.[note 3][3] What became evident at an early stage in Stott's development was his preference for rural themes and a penchant for the domestic depiction of rural life and of children. The use of green in differing tonal shades is predominant in The Helping Hand of a Small Friend and reminiscent of the atelier of Carolus Duran whilst The High Grasses possesses a softer, more tonal application. In terms of subject matter there is a strong influence of the naturalism of Bastien-Lepage. A necessary component of an art student in Paris’ experience was to spend time in une colonie artistique (an artists’ colony) away from the city in a setting where ideas were discussed and alliances were made. Edward Stott opted for Auvers-sur-Oise, northeast of Paris, a rural habitué visited in the past by many artists from Corot to Van Gogh who is buried in the Auvers-sur-Oise municipal cemetery.[8]

Return to England

On Stott's return to England he became something of a peripatetic traveller as he searched for an appropriate rural environment from where he could sketch and paint. Stott was enthralled by a notion that many late Victorians felt, that the true values of Merrie England were to be found in bucolic rural idylls. The reality was that the rural economy was in a parlous state in the latter part of the nineteenth century and was irrevocably changing with many thousands of poorly paid agricultural workers leaving the land for the towns and cities. As their exodus gathered pace many rural trades and skills were also disappearing for good. The viewer of Stott's paintings gets little notion of the reality of life in the English countryside that for many rural Britons remained hard and toilsome.[9]

Initially Stott visited a Paris contemporary, Philip Wilson Steer in Walberswick, Suffolk. Steer and Stott were advocates of En plein air painting, essentially a method of painting outdoors, generally credited to Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750–1819),[10] that he expounded in a treatise entitled Reflections and Advice to a Student on Painting, Particularly on Landscape (1800) developing the concept of ‘landscape portraiture’ by which the artist paints directly onto canvas in situ within the landscape, a method that enabled a skilled artist to capture the changing details and light.[10] It was an influential theory whose baton was taken up by later generations of French artists including the Barbizon School where its application by artists that included: Charles-François Daubigny, Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet allowed for a more accurate depiction of outdoor settings in various light and weather conditions.[11] Stott was always drawn to painting the countryside at differing times of the day where he could respond to the changing light and the tonal changes of colour.

Whilst at Walberswick, Stott made a lasting relationship with an Irish painter Walter Osborne (1859–1903)[12] with whom he shared his passion for the rural landscape. Stott's work at this time included a number of pastel sketches including Sheep in a Suffolk Landscape (1884) an early example of a subject matter that Stott would often revisit. Stott also sent three pictures to the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, a newly founded association. In 1884 he sent Amateurs(1884) (whereabouts is unknown), Complete Angler (1885) and The Harvest Moon (1886) (whereabouts also unknown). Amateurs for which sketches survive wrought the ire of one critic who described it as 'French', a work as 'failing to put in any values, and entirely refusing to recognise the existence of any interest save the interest of paint'.[3] It was a harsh criticism that upset the sensitive Stott but it confirms that the impressionistic representation of art remained controversial and radical to many art critics of the period.[13] In general there was a lack of a positive response to the young French-trained artists, judging by a selection of critical notices that they garnered amongst the art establishment of the time. The same antagonism that had been pointed at Bastien-Lepage, Clausen and, La Thangue in the early 1880s was still prevalent for their acolytes.[14]

New English Art Club

.jpg.webp)

The response to the criticism was the formation of New English Art Club (NEAC) in 1885 by an impressive array of around fifty young British artists that included Edward Stott. Its founding premise was to allow the founding artists to exhibit their own works and to exclude those that were deemed not to their taste. The association held an Annual Exhibition in 1886, a riposte to the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy of Arts that was passively rejecting works by younger artists. Amongst the founding members who exhibited were future stalwarts of the establishment including: Stanhope Forbes, Elisabeth Forbes, Henry Tuke, George Clausen, Steer and Osborne and in 1888 they were joined by Walter Sickert. Stott exhibited two rural scenes at the 1887 New English Art Club exhibition including The Ferry Boat (1887) a painting set in Winchelsea, East Sussex and described by Stott's biographer Valerie Webb as ‘an early consummate work’.[15] Stott showed at least twenty works at the New English Art Club between 1888 and 1895, the majority of which are missing. A major work by Stott, On a Summer’s Evening (1892), represents his continuing fascination with the tonal differences of light and shade. The NEAC still exists but within a few years of its founding its Avant-garde mission had given way to more conservative tendencies akin to that of the Royal Academy.[14] [16]

In 1886 Stott placed a picture at the Grosvenor Gallery Summer Exhibition. The Grosvenor, which had been founded in 1877, was a gallery and not an academy and thus prepared to offer young artists wall space including Edward Stott's portrait of a young child entitled Mollie which received commendations from The Illustrated London News in 1886.[17][14] He also exhibited: Feeding the Ducks (1885) and Winter’s Night, Sussex Village (1887) the former illustrative of Stott's debt to the work of Bastien-Lapage. In 1888 the New Gallery opened in Regent Street, London. It followed a disagreement amongst the directors of the Grosvenor Gallery and the gallery's owner Sir Coutts Lindsay, which resulted in two directors, the drama and art critic J. Comyns Carr and the painter and gallery administrator C.E. Hallé leaving to open a new gallery and taking with them established artists that included Alma-Tadema, George Frederic Watts and the Royal Academy President Frederic Leighton. It proved a fatal intervention for the Grosvenor which closed in 1890 but a boon for younger artists such as Edward Stott, now aged thirty-three as the founding mission included an offer of exhibition space to experimental and progressive artists. The New Gallery held its inaugural summer exhibition in 1886 followed in October by the first exhibition of industrial and applied arts by the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society under the direction of its founding president, Walter Crane.[18]

Stott was joined at the New Gallery by familiar faces: La Thangue, Osborne, Steer, and Alfred East were amongst those artists who had exhibited at the New English Club. Stott chose a familiar rural scene for the Summer Exhibition with a painting entitled Trees Old and Young, Sprouting a Shady Boon for Simple Sheep (1888). The uncomely title harked back to the romantic poet John Keats and his poem of shepherd-hunter Endymion published in 1818 and represented a brief period in Stott's career where poetry and art were intertwined. Idyllic rural settings were by now established themes and Stott chose In an Orchard – An Early Summer Morning (1892) and Changing Pastures (1893). The latter is an intimate painting of a young cowgirl leading her herd from one field to the next in the gloaming light at the end of the day. The setting sun was a leitmotif of Stott and many of his paintings are executed in the twilight, leading to one critic to describe him as ‘the poet-painter of the twilight’[19] Three paintings exhibited at the New Gallery: The Horse Pond (1891), Noonday (1895) and The Golden Moon (1896) are more experimental in their use of colour lacking non-essential detail. The figure of the boy astride the horse in the former is impressionistic, his features deliberately simplified. There is a timeless, unchanging quality to these paintings where atmosphere and nostalgia predominate at the expense of realism.[3]

Stott at Amberley, Sussex

In 1885 Stott visited the village of Amberley in West Sussex for the first time and by 1887 he was living there permanently. He was to stay in Amberley until his death in 1918 recording the lives of its inhabitants at work and at play. He immersed himself in the landscape of chalk downs, undulating meadows and the wild brooks of the River Arun that flooded in the winter. It was a vision of a perfect English village unencumbered by the advance of industrialisation and urbanisation. Some Victorians had convinced themselves of the moral turpitude of the urbanised working class. Their response was to look back to an Avalon of the mind. Stott's paintings provided balm and succour that the countryside remained an unchanging idyll.[20] The truth was that Amberley, was a living village populated by real people in need of alternative employment. The production of lime from the Amberley chalk quarry became a source of employment to some local people previously employed as agricultural workers.[21] A railway station was opened in 1863 by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway providing ready access to London and to coastal conurbations of Portsmouth and Brighton. It passed a few hundred metres from the ancient Amberley Castle walls and bought day-trippers to fish the trout waters of the Arun whilst boaters navigated the river to nearby Houghton Bridge. There were duck shooters on the Amberley Brooks in the winter months and artists drawn to the lovely landscape and ever changing light.[3]

Stott became something of a reluctant celebrity to this changing group of aspiring artists that included: the early aviator and landscape artist Jose Weiss (1859–1919) and Arthur Winter Shaw (1869–1948), the latter demonstrably inspired by Stott, Gerald Burn (1862–1945), an etcher and engraver, and watercolorist Felicia Lievan Bauwens. The garrulous and extrovert Fred Stratton, father of the sculptor Hilary Stratton, lived at Amberley from where he entertained well-disposed friends such as Eric Gill and the composer John Ireland, who composed Amberley Wild Brooks in 1921, following a visit to Stratton. The American writer Gladys Huntington was also a resident. Edyth Starkie, portrait painter and sculptor and her husband Arthur Rackham the illustrator lived in Amberley for ten years in the 1920s.[22][23]

Stott’s paintings of Amberley

Stott's first Amberley-themed paintings are Amberley, Sussex (1885) and Primrose Time (1885); the whereabouts of both are presently unknown but by the end of the 1880s, Stott was producing paintings that featured the domestic and working lives of its inhabitants and of the countryside in which they lived. They demonstrated an artist who was moving away from rustic naturalism, in particular in his representation of figures. The toil of working the fields all day is missing whilst the individual tasks of harvesting and ploughing seemingly imply the merest of efforts. These depictions are typical of the period in which they were painted[24] In Harvesters (undated), the figures of the women blend, almost meld into the landscape.

_-_Red_Roses_-_1214773_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

A series of four paintings of young cowherds were executed between 1888 and 1907. The Young Cowherd (1888) was exhibited at the New Gallery and is closer stylistic to the techniques that Stott learnt in Paris. The harmony of colour and tone is reminiscent of Corot and places Stott within a wider European context[3] The final picture in the sequence, Folding Time (1904), bears a noticeable affinity to the work of Eugène Chigot, a contemporary of Stott under Cabanel at the École des Beaux-Arts. In a series of paintings themed around young women in an orchard he explored the boundary between the public and private world. Many Sussex houses had small orchards and cider-making was an established practice across Sussex and Kent.[note 4]In Birdcage (1905), the rustic innocence of the girl is achieved through the use of muted greens, pinks and greys. The subject has on a red dress, a favourite colour for his female subjects. It is an idealised image of femininity. Stott remained single all his life and apparently regarded marriage as not conducive to the vocation of an artist.[3] Stott recorded families and workers returning home at eventide. It was a theme to which he returned often throughout his years. His fascination with the gloaming light at dusk was often revisited in Stott's paintings. They include Home by the Ferry (1891) and The Harvester’s Return (1899) at opposite ends of the decade. The latter was enthusiastically received as conveying the feeling of a long and tiring traipse after the workers had finished their work.[25]

Many Victorians possessed a somewhat sentimentalised view of childhood and genre paintings of children such as those produced by William Henry Gore and Blanche Jenkins amongst numerous others were immensely popular.[26] Stott had commercial and international critical success with a number of his paintings depicting children at play. They possess a tenderness that suggests an affinity with children. The Old Gate (1895) was chosen for a major art exhibition in Munich. It shows a boy and a team of plough horses returning home on a late summer's evening where they are welcomed by two young girls bathed in the shadows of a late evening sun. Stott presents a painting in tune with the sensibilities of his audience that rural life was stable and permanent and built on rituals of hard work. The painting which is now owned by the Manchester Art Gallery was subsequently shown at the Brussels Exposition in 1897 and at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900, possibly at the request of Stott's friend and patron Isidore Spielmann.[3]

Stott must have been a familiar figure in the village by 1900 with access to the interiors of many of Amberley's inhabitants. Stott remained unmarried but found domestic contentment with the Dinnage family with whom he formed a close bond. Anne Dinnage became his companion and helper. [3] He began to paint reassuring domestic scenes of mothers and children including Washing Day (1899) and a separate painting Washing Day (1906). Stott's rustic interiors that include A Cottage Madonna (1907) were about an England of morality and domestic harmony where the sexes were content with their respective roles. There are no troublesome women protesting for Women's Suffrage, a major issue in Edwardian society especially after the Liberal Party landslide of 1906.[27] Nor is there any sign of the influence of the new radical art movements that included the Fauvists and the Cubists that began to gain critical traction in France and the United Kingdom.[28] Stott's work is far removed from the radical creations of the already departed Beardsley (1872–1898) for example. It is no coincidence that the majority of Stott's paintings of this period were exhibited at that bastion of conservative values namely the Royal Academy to which he was duly elected an Associate in 1906.[3]

Final years in Sussex

_81.6_x_106_cm%252C_Ferrens_Art_Gallery%252C_Hull.jpg.webp)

Stott had moved into a new studio by 1910. A period of re-evaluation and reflection is evident in his work in the final years of his life. He chose to return to the art of his days as a student in Paris, when to aid his drawing and sketching, he had studied the Old Masters. He created a series of religious and biblical images that he placed within the Sussex landscape. There were three paintings with the theme of the Mother of God and Christ in the period 1907 to 1917 including Two Mothers (1909) where he depicts a mother with two children. She is holding a lamb, a motif for the Lamb of God. A ewe is painted suckling another lamb. The art critic Paul George Konody was fulsome in his praise calling the image 'a modernist Madonna of the Meadows'.[29] In 1910 after completing many preparatory sketches, Stott sent one of his most popular paintings The Good Samaritan to the Royal Academy. The Times art critic described it as ‘tender and charming, with something of the sentiment of Rembrandt’[30] whilst the Art Journal wrote of the 'mystery and 'truth' of the painting. It was, however, atypical of most of the pictures hung in 1910 with portraiture predominating at the Exhibition.[31][32]

A number of other modernist allegorical paintings of biblical subjects were also executed in the final decade of his life including the atmospheric, dark-toned Flight into Egypt (1909). It has a portentous feeling and was well received by The Guardian critic when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy.[33] Stott produced three pictures for the 1916 Royal Academy Summer exhibition that reflected his preferred subject matters. The Prodical’s Return (1916) continued his series of biblical studies; The Piping Shepherd Boy (1916) was a throwback to the rustic subject matter of the late 1890s and A Summer Moon (1916) an experimental study of atmospheric effects. One of Stott's final exhibited biblical works The Holy Family (1917) which he struggled to finish because of poor health is presented as a tondo.[34] A final unfinished tondo picture depicting a youthful Orpheus was exhibited posthumously at the Summer Exhibition in 1918.[35]

Edward Stott died at his home in Amberley on 19 March 1918. His memorial stone stands against the east wall of St Michael's churchyard and is an impressive two metres in height. The head carving is by the sculptor Francis Derwent Wood, a neighbour of Stott. The bas-relief on the Portland Stone monument is of a wreathed Orpheus with his lyre.[36] In the church there is a memorial stained-glass window by Robert Anning Bell with a central section recreating Stott's The Entombment (1917)[37]

Notes

- ↑ Stott used his middle name for commercial purposes to avoid confusion with an Oldham artist called William Stott (1857–1900). As both were from mill-owning families and contemporaries who studied in Paris the confusion was perhaps inevitable. It may explain why each Stott chose different French artistic colonies within which to work.

- ↑ There is yet another William Stott working in this period. William Robertson Smith Stott (1870–1939) was a painter and illustrator of portraits, figures and landscape in oil who lived in Aberdeen and later moved to Chelsea. He exhibited twenty-two works at the Royal Academy between 1905–1934.

- ↑ The paintings were exhibited with French titles: On a servent besoin d’un plus petit du soin (The Helping Hand of a Small Friend); Les Hautes Herbes (The High Grasses); Retour du Poulailler (The Return to the Poultry House).

- ↑ The practice of part paying agricultural workers for their labours with cider (and other foods and drink) was commonplace for most of the nineteenth century and was only abolished with the Truck Act 1887.

Biography

- Valerie Webb (2018), Edward Stott (1855–1918): A Master of Colour and Atmosphere, Samsom & Company, Bristol, England. ISBN 9781911408222

Bibliography (selected)

- Jeremy Maas,(1988) Victorian Painters, Random House Value Pub; Reissue edition ISBN 051767131X

- Denney, Colleen (2000). At the Temple of Art: the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877–1890. Issue 1165. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0838638503

- Margaretta Frederick Watson, (1997) Collecting The Pre-Raphaelites: The Anglo-American Enchantment, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Aldershot, Hants,

- Joshua C. Taylor (1989). Nineteenth-Century Theories of Art. University of California Press. ISBN 0520048881.

- Malcolm Warner (1996), The Victorians: British Painting 1837–1901, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. ISBN 0810963426

- Brian Stewart & Mervyn Cutten, (1997), The Dictionary of Portrait Painters in Britain up to 1920, Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 185149173 2

Gallery (selected)

Self Portrait

Self Portrait The labourer's cottage – suppertime

The labourer's cottage – suppertime pastel titled Sheep at Eventide

pastel titled Sheep at Eventide Trees, a shady boon for simple sheep

Trees, a shady boon for simple sheep_-_Changing_Pastures_-_N03670_-_National_Gallery.jpg.webp) Changing Pastures

Changing Pastures_-_The_Watering_Place_-_1214772_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp) The Watering Place

The Watering Place.jpg.webp) The Old Gate (1896)

The Old Gate (1896)%252C_oil_painting_74.8_x_60.1_cm_Laing_Art_Gallery%252C_Newcastle-upon-Tyne.%252C_%252C.jpg.webp) The Widow's Acre (1900)

The Widow's Acre (1900).jpg.webp) Untitled pastel by Stott

Untitled pastel by Stott pastel titled Flight into Egypt

pastel titled Flight into Egypt Peaceful rest (1902)

Peaceful rest (1902) Riding the Farm horse

Riding the Farm horse Home by the Ferry

Home by the Ferry.jpg.webp) The Bird Cage (1905)

The Bird Cage (1905) Echo

Echo.jpg.webp) Feeding the Ducks

Feeding the Ducks.jpg.webp) Sunday Morning (1901)

Sunday Morning (1901).jpg.webp) Chalk Pit near Amberley (1903)

Chalk Pit near Amberley (1903) Edward Stott Memorial

Edward Stott Memorial Memorial headstone of Stott, Amberley, West Sussex

Memorial headstone of Stott, Amberley, West Sussex Stott Memorial window by Anning Bell (1919)

Stott Memorial window by Anning Bell (1919)

References

- ↑ Szabolcsi, (1970) The Decline of Romanticism: End of the Century, Turn of the Century-Introductory Sketch of an Essay, Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.

- ↑ D. A. Little (1979), The English Cotton Industry and the World Market 1815–1896, Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198224788

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Valerie Webb (2018), Edward Stott (1855 – 1918): A Master of Colour and Atmosphere, Sansom & Company, Bristol, England. ISBN 9781911408222

- ↑ Collectif, (2003), Carolus Duran 1837-1917, RMN Arts Du 19E Expositions, (in French) ISBN 9782711845538

- ↑ James Harding, 1979. Artistes pompiers: French academic art in the 19th century, New York: Rizzoli, ISBN 9780856704512

- ↑ Andreas Bluhm, (2011) Alexandre Cabanel: The Tradition of Beauty, Hirmer Verlag, Munich, Germany.

- ↑ Hugh Honour and J.A. Fleming,(2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 9781856695848

- ↑ Sweetman, David (1990). Van Gogh: His Life and His Art. Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-671-74338-3.

- ↑ Alun Howkins (1991). Reshaping Rural England. A Social History 1850-1925. Harper Collins Academic

- 1 2 Joshua Taylor (1989), Nineteenth Century Theories of Art, pages 246-7, University of California Press, USA. ISBN 0520048881

- ↑ Auricchio, Laura (2004). "The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ↑ http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/irish-artists/walter-osborne.htm Walter Frederick Osborne visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 20 May 2017

- ↑ Véronique Bouruet Aubertot (2017), Impressionism: The Movement that Transformed Western Art, AVA Publishing SA, ISBN 9782080203205

- 1 2 3 Coleen Denney (2000). At the Temple of Art: the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877–1890. Page 188. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0838638503

- ↑ Valerie Webb (2018), Edward Stott (1855 – 1918): A Master of Colour and Atmosphere, page 47, Sansom & Company, Bristol, England. ISBN 9781911408222

- ↑ https://www.artbiogs.co.uk/2/societies/new-english-art-club New English Art Club.

- ↑ Illustrated London News 89, May 8, 1886

- ↑ "New Gallery (Regent Street, London) | Organisations | RA Collection | Royal Academy of Arts".

- ↑ https://www.townereastbourne.org.uk/exhibition/edward-stott-master-colour-atmosphere/ Edward Stott: A Master of Colour and Atmosphere, Towner Gallery, Eastbourne Exhibition (2018).

- ↑ Malcolm Warner (1996), The Victorians: British Painting 1837–1901, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.ISBN 0810963426

- ↑ Records of Frank Montague Pepper of Amberley, and Dr. Frank R. Pepper of Pulborough. National Archive: West Sussex Records Office Add. Mss. 37, 527 - 37,537 1899-1978

- ↑ http://www.amberleysociety.org.uk/artists.html Amberley Society (2013)

- ↑ Victorian Painters: Dictionary of British Art, (1995)

- ↑ Nina Lubbren, (2001) Rural artists’ colonies in Europe, 1870 - 1910, Manchester University Press)

- ↑ The Daily News, 7 April 1900

- ↑ Brian Stewart & Mervyn Cutten, (1997), The Dictionary of Portrait Painters in Britain up to 1920, Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 185149173 2

- ↑ Craig, F. W. S. (1974), British Parliamentary Election Results, 1885–1918, Macmillan

- ↑ Josef Helfenstein’ Eva Reifert, The Cubist Cosmos: From Picasso to Léger, Hirmer publishing. ISBN 3777432628

- ↑ P.G. Konody, ‘A Critical Survey’ Observer 2 May 1909

- ↑ The Royal Academy”, The Times, Saturday 30 April 1910

- ↑ A.C.R. Carter, “The Royal Academy: A General Survey”, The Art-Journal, June 1910, 163/164

- ↑ https://chronicle250.com/1910#footnote_chapter__text-4-link Morna O'Neill, Associate Professor at Wake Forest University, 1910 The Politics of Portraiture

- ↑ Laurence Housman, The Guardian, 11 May 1906

- ↑ http://www.artnet.com/artists/edward-stott/the-holy-family-Cq3sOYUoQaF9wdel2JB2Mw2>

- ↑ Mallett, mark; Turner, Sarah Victoria (2018). The Great Spectacle: 250 Years of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. London: Royal Academy of Arts. p. 208. ISBN 9781910350706.

- ↑ "Object Details | Public Sculptures of Sussex".

- ↑ Farrow, Rob. "St Michael - Window in top of door arch". Geograph. Retrieved 22 November 2022.