The Grosvenor Gallery was an art gallery in London founded in 1877 by Sir Coutts Lindsay and his wife Blanche. Its first directors were J. Comyns Carr and Charles Hallé. The gallery proved crucial to the Aesthetic Movement because it provided a home for those artists whose approaches the more classical and conservative Royal Academy did not welcome, such as Edward Burne-Jones and Walter Crane.[1]

History

The gallery was founded in Bond Street, London, in 1877 by Sir Coutts Lindsay and his wife Blanche. They engaged J. Comyns Carr and Charles Hallé as co-directors. Lindsay and his wife were well-born and well-connected, and both were amateur artists. Blanche was born a Rothschild, and it was her money which made the whole enterprise possible.[1]

The Grosvenor displayed work by artists from outside the British mainstream, including Edward Burne-Jones, Walter Crane and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. But it also featured work by others that were widely shown elsewhere, including the Royal Academy, such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Edward John Poynter and James Tissot. In 1877 John Ruskin visited the gallery to see work by Burne-Jones. An exhibition of paintings by James McNeill Whistler was also on display. Ruskin's savage review of Whistler's work led to a famous libel case, brought by the artist against the critic. Whistler won a farthing in damages. The case made the gallery famous as the home of the Aesthetic movement, which was satirised in Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience, which includes the line, "greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery".[2] The enterprising art critic Henry Blackburn issued illustrated guides to the annual exhibitions under the title Grosvenor Notes (1877–82).

In 1888, after a disagreement with Lindsay, Comyns Carr and Hallé resigned from the gallery to found the rival New Gallery, capturing Burne-Jones and many of the Grosvenor Gallery's other artists. The break-up of his marriage, financial constraints and personal conflicts forced Lindsay out of the gallery, which was taken over by his estranged wife.[1]

Revivals

After its closure in 1890 the Grosvenor Gallery name was revived twice by unrelated ventures:

- in October 1912, P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. and Knoedler opened a new Grosvenor Gallery at 51a New Bond Street, appointing the American-born artist and critic Francis Howard, who worked for Knoedler, as the managing director.[3][4][5] The Gallery was planned to be one of the largest and finest in London and had six rooms.[6] There was an appeal to raise funds to purchase the lease from the Colnaghis,[7] but in January 1920 the Daily Mirror announced that the gallery was due to be shut due to problems with funding.[8] The gallery was reopened in February 1921, under the sole proprietorship of the Colnaghis, with an exhibition of living artists.[9] However, it finally closed in 1924, with the Colnaghis stating that the problem was not so much finance, even though the gallery did not pay its way, but the difficulty of finding 1,000 new works of an adequate quality every year.[10]

- in October 1960, the American art collector, dealer, and author Eric Estorick opened a new Grosvenor Gallery at 15 Davies Street with a display of modern sculpture.[11] The gallery was still operating in 2020.[12]

Generating station

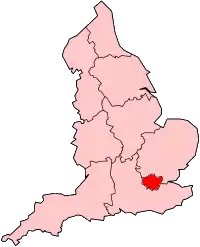

Upon returning from the Paris Exhibition of 1882, the Earl of Crawford recommended that Lindsay install electric lighting in the gallery. In 1883, two Marshall engines, each belted to a Siemens alternator, were installed in a yard behind the gallery. The installation was a success, and neighbours began requesting a supply. Lindsay, Crawford and Lord Wantage then set up the Sir Coutts Lindsay Co. Ltd., and in 1885 constructed the Grosvenor Power Station. This was constructed under the gallery and had a capacity of 1,000 kilowatts. The station supplied an area reaching as far north as Regent's Park, the River Thames to the south, Knightsbridge to the west and the High Court of Justice to the east. However the system caused a lot of trouble, so much so that Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti gave advice as to how to resolve it in 1885; by January 1886 Farranti was Chief Engineer and within a few months reworked the system to include a Hick, Hargreaves Corliss engine and two alternators to his own design as replacements for the Siemens equipment. The station was made a substation with the opening of Deptford Power Station.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sheppard, F. H. W. (general editor) (1980). 'Bourdon Street and Grosvenor Hill Area', Survey of London; vol. 40: The Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings). Institute of Historical Research. pp. 57–63. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - 1 2 Teukolsky, Rachel (2009). The Literate Eye: Victorian Art Writing and Modernist Aesthetics (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 9780195381375. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ "The Grosvenor Galleries". The Times (Tuesday 25 January 1921): 6. 25 January 1921. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "Grosvenor Gallery". Artist Biographies. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ↑ "The New Grosvenor Gallery". Westminster Gazette (Tuesday 08 October 1912): 3. 8 October 1912. Retrieved 13 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Portraits of Fair Children". The Times (Tuesday 12 March 1912): 4. 12 March 1912. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "The Grosvenor Gallery". The Times (Thursday 06 November 1919): 8. 6 November 1919. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "Grosvenor Galleries". Daily Mirror (Monday 19 January 1920): 11. 19 January 1920. Retrieved 13 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London Letter: Mr James M'Bey's Portraits". Aberdeen Press and Journal (Friday 11 February 1921): 4. 11 February 1921. Retrieved 13 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "The Grosvenor Galleries". The Times (Thursday 13 March 1924): 11. 13 March 1924. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "A New Grosvenor Gallery". The Times (Monday 17 October 1960): 8. 17 October 1960. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "About". Grosvenor Gallery. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

Sources and further reading

- Denney, Colleen (2000). At the Temple of Art: the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877–1890. Vol. Issue 1165. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-3850-3.

- Hannah, Leslie (1979). Electricity Before Nationalisation, A Study in the Development of the Electricity Supply Industry in Britain to 1948. London & Basingstoke: Macmillan Publishers for the Electricity Council. ISBN 0-8018-2145-2.

- Lambourne, Lionel (1996). The Aesthetic Movement. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3000-3.

- Snodin, Michael; Styles, John (2001). Design & The Decorative Arts, Britain 1500–1900. London: V&A Publications. ISBN 1-85177-338-X.