England traditionally celebrates a number of Christian and secular festivals. Most are observed throughout the country but some, such as Oak Apple Day, Souling, Rushbearing, Bawming the Thorn, and Hocktide, are local to certain regions.

New Year's Day

New Year's Day is observed on 1 January. The festivities begin a day before on 31 December when parties are held to bring in the new year. Public events are also organised where firework displays are arranged.

According to Whistler (2015), during the 18th century, first footing was not known in the South of England. Instead, "glasses were raised at quarter to twelve to "the Old Friend-Farewell!Farewell!Farewell!" and then at midnight to "the New Infant" with three ' Hip, hip horrahs!'". Other customs included dancing in the New Year. In the North of England, first footing has been traditionally observed involving opening the door to a stranger at midnight.[1] The guest is seen as a bringer of good fortune for the coming year.[2][3]

In Allendale, the town's New Year celebrations involve lighted tar barrels that are carried on the heads of revellers called guisers. This tradition dates back to 1858. It appears to have originated from the lighting of a silver band that were carolling at New Year. They were unable to use candles to light their music due to the strong winds, so someone suggested a tar barrel be used. Having to move from place to place, it would have been easier to carry the barrels upon the guisers' heads, rather than rolling them. There have been claims that it is a pagan festival, however, these claims are unfounded.[4]

Plough Monday

Plough Monday is the traditional start of the English agricultural year. While local practices may vary, Plough Monday is generally the first Monday after Twelfth Day (Epiphany), 6 January.[5][6] References to Plough Monday date back to the late 15th century.[6] The day before Plough Monday is sometimes referred to as Plough Sunday.

The day traditionally saw the resumption of work after the Christmas period in some areas, particularly in northern England and East England.[7]

The customs observed on Plough Monday varied by region, but a common feature to a lesser or greater extent was for a plough to be hauled from house to house in a procession, collecting money. They were often accompanied by musicians, an old woman or a boy dressed as an old woman, called the "Bessy," and a man in the role of the "fool." 'Plough Pudding' is a boiled suet pudding, containing meat and onions. It is from Norfolk and is eaten on Plough Monday.[5]

Instead of pulling a decorated plough, during the 19th century, men or boys would dress in a layer of straw and were known as Straw Bears who begged door to door for money. The tradition is maintained annually in January, in Whittlesey, near Peterborough where on the preceding Saturday, "the Straw Bear is paraded through the streets of Whittlesey".[8]

Saint Valentine's Day

Saint Valentine's Day, also known as the Feast of Saint Valentine,[9] is celebrated annually on 14 February. Originating as a Western Christian feast day honouring one or two early saints named Valentinus, Saint Valentine's Day is recognized as a significant cultural, religious, and commercial celebration of romance and romantic love, although it is not a public holiday.

Martyrdom stories associated with various Valentines connected to 14 February are presented in martyrologies,[10] including a written account of Saint Valentine of Rome imprisonment for performing weddings for soldiers, who were forbidden to marry and for ministering to Christians persecuted under the Roman Empire.[11] According to legend, during his imprisonment Saint Valentine restored sight to the blind daughter of his judge,[12] and before his execution, he wrote her a letter signed "Your Valentine" as a farewell.[13]

The day first became associated with romantic love within the circle of Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century, when the tradition of courtly love flourished. In 18th-century England, it evolved into an occasion in which lovers expressed their love for each other by presenting flowers, offering confectionery, and sending greeting cards (known as "valentines"). Valentine's Day symbols that are used today include the heart-shaped outline, doves, and the figure of the winged Cupid. Since the 19th century, handwritten valentines have given way to mass-produced greeting cards.[14] In Europe, Saint Valentine's Keys are given to lovers "as a romantic symbol and an invitation to unlock the giver’s heart", as well as to children, in order to ward off epilepsy (called Saint Valentine's Malady).[15]

Saint Valentine's Day is an official feast day in the Anglican Communion[16] and the Lutheran Church.[17] Many parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church also celebrate Saint Valentine's Day, albeit on 6 July and 30 July, the former date in honor of the Roman presbyter Saint Valentine, and the latter date in honor of Hieromartyr Valentine, the Bishop of Interamna (modern Terni).[18]

Traditions include sending cards, flowers, chocolates and other gifts. Valentine's Day in England still remains connected with various regional customs. In Norfolk, a character called 'Jack' Valentine knocks on the rear door of houses leaving sweets and presents for children. Although he was leaving treats, many children were scared of this mystical person.[19][20]

Mothering Sunday (Mothers Day)

The United Kingdom celebrates Mothering Sunday, which falls on the fourth Sunday of Lent. This holiday has its roots in the church and was originally unrelated to the American holiday.[21][22] Most historians believe that Mothering Sunday evolved from the 16th-century Christian practice of visiting one's mother church annually on Laetare Sunday.[23] As a result of this tradition, most mothers were reunited with their children on this day when young apprentices and young women in service were released by their masters for that weekend. As a result of the influence of the American Mother's Day, Mothering Sunday transformed into the tradition of showing appreciation to one's mother.

Easter

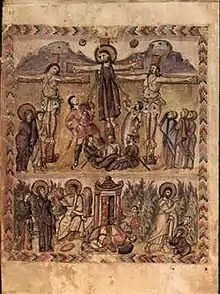

The celebration of Easter Day is not fixed and is a movable observance. Easter Day, also known as Resurrection Sunday, marks the high point of the Christian year. It is a festival and holiday celebrating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in the New Testament as having occurred on the third day of his burial after his crucifixion by the Romans at Calvary c. 30 AD.[24][25] It is the culmination of the Passion of Jesus, preceded by Lent (or Great Lent), a forty-day period of fasting, prayer, and penance.

In the United Kingdom, both Good Friday and Easter Monday are bank holidays.[26] Traditions include going to Church, eating Easter Eggs and hot-cross buns. In the north of England, the traditions of rolling decorated eggs down steep hills and pace egging are still adhered to today.

Hocktide

Hocktide is a very old term used to denote the Monday and Tuesday in the second week after Easter.[27] It was an English mediaeval festival; both the Tuesday and the preceding Monday were the Hock-days. Together with Whitsuntide and the twelve days of Christmastide, the week following Easter marked the only vacations of the husbandman's year, during slack times in the cycle of the year when the villein ceased work on his lord's demesne, and most likely on his own land as well.[28]

At Coventry, there was a play called The Old Coventry Play of Hock Tuesday. This, suppressed at the Reformation owing to the incidental disorder that accompanied it, and revived as part of the festivities on Queen Elizabeth's visit to Kenilworth in July 1575, depicted the struggle between Saxons and Danes, and has given colour to the suggestion that hock-tide was originally a commemoration of the massacre of the Danes on St. Brice's Day, 13 November 1002, or of the rejoicings at the death of Harthacanute on 8 June 1042 and the expulsion of the Danes. But the dates of these anniversaries do not bear this out.[29][27]

In England as of 2017 the tradition survives only in Hungerford in Berkshire, although the festival was somewhat modified to celebrate the patronage of the Duchy of Lancaster. John of Gaunt, the 1st Duke of Lancaster, granted grazing rights and permission to fish in the River Kennet to the commoners of Hungerford. Despite a legal battle during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) when the Duchy attempted to regain the lucrative fishing rights, the case was eventually settled in the townspeople's favour after the Queen herself interceded. Hocktide in Hungerford now combines the ceremonial collecting of the rents with something of the previous tradition of demanding kisses or money.

Although the Hocktide celebrations take place over several days, the main festivities occur on the Tuesday, which is also known as Tutti Day. The Hocktide Council, which is elected on the previous Friday, appoints two Tutti Men whose job it is to visit the properties attracting Commoner's Rights. Formerly they collected rents, and they accompanied the Bellman (or Town crier) to summon commoners to attend the Hocktide Court in the Town Hall, and to fine those who were unable to attend one penny, in lieu of the loss of their rights. The Tutti Men carry Tutti Poles: wooden staffs topped with bunches of flowers and a cloved orange. These are thought to have derived from nosegays which would have mitigated the smell of some of the less salubrious parts of the town in times past. The Tutti Men are accompanied by the Orange Man (or Orange Scrambler) - who wears a hat decorated with feathers and carries a white sack filled with oranges - and Tutti Wenches who give out oranges and sweets to the crowds in return for pennies or kisses.

The proceedings start at 8 am with the sounding of the horn from the Town Hall steps. This summons all the commoners to attend the Court at 9 am, after which the Tutti Men visit each of the 102 houses in turn. They no longer collect rents, but demand a penny or a kiss from the lady of the house when they visit. In return, the Orange Man gives the owner an orange.

After the parade of the Tutti Men through the streets the Hocktide Lunch takes place for the Hocktide Council, commoners and guests, at which the traditional "Plantagenet Punch" is served. After the meal, an initiation ceremony, known as Shoeing the Colts is held, in which all first-time attendees are shod by the blacksmith. Their legs are held and a nail is driven into their shoe. They are not released until they shout "Punch". Oranges and heated coins are then thrown from the Town Hall steps to the children gathered outside.

April Fools' Day

April Fools' Day is an annual celebration commemorated on 1 April by playing practical jokes and spreading hoaxes. The jokes and their victims are called April fools. People playing April Fool jokes often expose their prank by shouting "April fool" at the unfortunate victim(s). Some newspapers, magazines and other published media report fake stories, which are usually explained the next day or below the news section in smaller letters. Although popular since the 19th century, the day is not a public holiday.

St. George's Day

Saint George's Day, also known as the Feast of Saint George, is the feast day of Saint George as celebrated on 23 April, the traditionally accepted date of the saint's death in the Diocletianic Persecution of AD 303.

St George's Day was a major feast and national holiday in England on a par with Christmas from the early 15th century.[30] The tradition of celebration St George's day had waned by the end of the 18th century after the union of England and Scotland.[31] Nevertheless, the link with St. George continues today, for example Salisbury holds an annual St. George's Day pageant, the origins of which are believed to go back to the 13th century.[32] In recent years the popularity of St. George's Day appears to be increasing gradually. BBC Radio 3 had a full programme of St. George's Day events in 2006, and Andrew Rosindell, Conservative MP for Romford, has been putting the argument forward in the House of Commons to make St. George's Day a public holiday. In early 2009, Mayor of London Boris Johnson spearheaded a campaign to encourage the celebration of St. George's Day. Today, St. George's day may be celebrated with anything English including morris dancing and Punch and Judy shows.[33]

A traditional custom on St George's day is to fly or adorn the St George's Cross flag in some way: pubs, in particular, can be seen on 23 April festooned with garlands of St George's crosses. It is customary for the hymn "Jerusalem" to be sung in cathedrals, churches and chapels on St George's Day, or on the Sunday closest to it. Traditional English food and drink may be consumed.

May Day

May Day Eve

Historically, on May Day Eve, fires were lit and sacrifices offered to obtain a blessing on the newly-sown fields.[34] According to Hutton (2001), England did not observe May Day Eve or May Day fires on a wide scale. There are however isolated instances of such fires in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire. However, the exceptions are Cumbria, Devon and Cornwall where May Day Eve or May Day fires were lit.[35] May-Day Eve night was also called " Mischief night".[36] According to Roud (2006), people in Lancashire, Yorkshire and surrounding counties played tricks on May Day Eve. Roud also states that there are isolated examples of an English folk belief that May Day Eve was connected to fairies. At the turn of the twentieth century, people in Herefordshire at Kingstone and Thruxton left "trays of moss outside their doors for the fairies to dance upon".[37]

May Day

Start of Summer on the first day of May, the traditional English May Day rites and celebrations include crowning a May Queen and celebrations involving a maypole. Historically, Morris dancing has been linked to May Day celebrations.[38] Much of this tradition derives from the pagan Anglo-Saxon customs held during "Þrimilci-mōnaþ"[39] (the Old English name for the month of May meaning Month of Three Milkings) along with many Celtic traditions.[40][41]

May Day has been a traditional day of festivities throughout the centuries, most associated with towns and villages celebrating springtime fertility (of the soil, livestock, and people) and revelry with village fetes and community gatherings. Seeding has been completed by this date and it was convenient to give farm labourers a day off. Perhaps the most significant of the traditions is the maypole, around which traditional dancers circle with ribbons. The spring bank holiday on the first Monday in May was created in 1978; May 1 itself is not a public holiday in England (unless it falls on a Monday).

Jack in the Green

Jack in the Green, also known as Jack o' the Green, is an English folk custom associated with the celebration of May Day. It involves a pyramidal or conical wicker or wooden framework that is decorated with foliage being worn by a person as part of a procession, often accompanied by musicians. Jack in the Green emerged within the context of English May Day processions, with the folklorist Roy Judge noting that these celebrations were not "a set, immutable pattern, but rather a fluid, moving process, which combined different elements at various times".[42] Judge thought it unlikely that the Jack in the Green itself existed much before 1770, due to an absence of either the name or the structure itself in any of the written accounts of visual depictions of English May Day processions from before that year.[43]

The Jack in the Green developed out of a tradition that was first recorded in the seventeenth century, which involved milkmaids decorating themselves for May Day.[44] In his diary, Samuel Pepys recorded observing a London May Day parade in 1667 in which milk-maids had "garlands upon their pails" and were dancing behind a fiddler.[44] A 1698 account described milk-maids carrying not a decorated milk-pail, but a silver plate on which they had formed a pyramid-shape of objects, decorated with ribbons and flowers, and carried atop their head. The milk-maids were accompanied by musicians playing either fiddle or bag-pipe, and went door to door, dancing for the residents, who gave them payment of some form.[45] In 1719, an account in The Tatler described a milk-maid "dancing before my door with the plate of half her customers on her head", while a 1712 account in The Spectator referred to "the ruddy Milk-Maid exerting herself in a most sprightly style under a Pyramid of Silver Tankards".[46] These and other sources indicate that this tradition was well-established by the eighteenth century.[47]

Revivals of the custom have occurred in various parts of England; Jacks in the Green have been seen in Bristol, Oxford and Knutsford, among other places. Jacks also appear at May Fairs in North America. In Deptford the Fowler's Troop and Blackheath Morris have been parading the tallest and heaviest modern Jack for many decades, either in Greenwich, Bermondsey and the Borough or at Deptford itself, and at the end of May a Jack is an essential part of the Pagan Pride parade in Holborn.

Oak Apple Day

Also known as Restoration Day, Oak Apple Day or Royal Oak Day, was an English public holiday, observed annually on 29 May, to commemorate the restoration of the English monarchy in May 1660.[48] In some parts of the country the day is still celebrated. In 1660, Parliament passed into law "An Act for a Perpetual Anniversary Thanksgiving on the Nine and Twentieth Day of May", declaring 29 May a public holiday "for keeping of a perpetual Anniversary, for a Day of Thanksgiving to God, for the great Blessing and Mercy he hath been graciously pleased to vouchsafe to the People of these Kingdoms, after their manifold and grievous Sufferings, in the Restoration of his Majesty..."[49] The public holiday was formally abolished in the Anniversary Days Observance Act 1859, however, events still take place at Upton-upon-Severn in Worcestershire, Marsh Gibbon in Buckinghamshire, Great Wishford in Wiltshire (when villagers gather wood in Grovely Wood), and Membury in Devon. The day is generally marked by re-enactment activities at Moseley Old Hall, West Midlands, one of the houses where Charles II hid in 1651. Celebrations include marching at Fownhope in Herefordshire holding flower and oak leaf decorated sticks.

At All Saints' Church, Northampton, a statue of Charles II is garlanded with oak leaves at noon every Oak Apple Day, followed by a celebration of the Holy Communion according to the Book of Common Prayer.[50][51]

Oak Apple Day is also celebrated in the Cornish village of St Neot.[50] The vicar leads a procession through the village, he is followed by the Tower Captain holding the Oak bough. A large number of the villagers follow walking to the Church. A story of the history of the event is told and then the vicar blesses the branch. The Tower Captain throws the old branch down from the top of the tower and a new one is hauled to the top. Everyone is then invited to the vicarage gardens for refreshments and a barbecue. Up to 12 noon villagers wear a sprig of "red" (new) oak and in the afternoon wear a sprig of "Boys Love" (Artemisia abrotanum); tradition dictates that the punishment for not doing this results in being stung by nettles.

Bawming the Thorn

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_60497.jpg.webp)

Each June, Appleton Thorn hosts the ceremony of "Bawming the Thorn". The current form of the ceremony dates from the 19th century, when it was part of the village's "walking day".[52] It involved children from Appleton Thorn Primary School walking through the village and holding sports and games at the school. This now takes place at the village hall. The ceremony stopped in the 1930s, but was revived by the then headmaster, Mr Bob Jones in the early 1970s. "Bawming the Thorn" occurs on the Saturday nearest to Midsummer's Day.

Bawming means "decorating" – during the ceremony the thorn tree is decorated with ribbons and garlands. According to legend, the hawthorn at Appleton Thorn grew from a cutting of the Holy Thorn at Glastonbury, which was itself said to have sprung from the staff of Joseph of Arimathea, the man who arranged for Jesus's burial after the crucifixion.[52]

Rushbearing

Rushbearing is an old English ecclesiastical festival in which rushes are collected and carried to be strewn on the floor of the parish church. The tradition dates back to the time when most buildings had earthen floors and rushes were used as a form of renewable floor covering for cleanliness and insulation. The festival was widespread in Britain from the Middle Ages and well established by the time of Shakespeare,[53] but had fallen into decline by the beginning of the 19th century, as church floors were flagged with stone. The custom was revived later in the 19th century and is kept alive today as an annual event in a number of towns and villages in the north of England. According to Roud (2006), Rushbearing ceremonies continue to take place in Warcop and Grasmere, in Cumbria.[54]

Lammas festival

Lammas, also known as Loaf Mass Day, is a Christian festival in the liturgical calendar to mark the blessing of the First Fruits of harvest, with a loaf of bread being brought to the church for this purpose.[55] Lammas is celebrated on 1 August, annually.[56] The name originates from the word "loaf" in reference to bread and "Mass" in reference to the Christian liturgy in which Holy Communion is celebrated.[57][58] It marks the annual wheat harvest, and is the first harvest festival of the year. On this day it is customary to bring to church a loaf made from the new crop. The loaf is blessed, and in Anglo-Saxon England,[59] lammas bread was broken into four bits, which were to be placed at the four corners of the barn, to protect the garnered grain. Christians also have church processions to bakeries, where those working therein are blessed by Christian clergy.[58]

The term Lammas "is a contraction of the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon expression Hláf mæsse, “from the hallowed bread [hláf—hence “loaf”] which is hallowed on Lammas Day".[60] According to Wilson (2011), "at Lammas, the fruits of the first cereal harvest were baked and used as an offering to make the grain storage barn safe".[61]

A recent revival of the festival has taken place in Eastbourne, in East Sussex.[62]

Harvest festival

Thanks have been given for successful harvests since pagan times. Harvest festival is traditionally held on the Sunday near or of the Harvest Moon. This is the full Moon that occurs closest to the autumn equinox (22 or 23 September). The celebrations on this day usually include singing hymns, praying, and decorating churches with baskets of fruit and food in the festival known as Harvest Festival. A community form of celebration known as Harvest Home has been observed in England since medieval times. The festival historically involved the local farmer giving dinner to those who helped to bring in the crops.[63]

Allhallowtide

The festival begins on 31 October. The term Halloween is derived from the phrase All Hallows Even which refers to the eve of the Christian festival of All Saint's held on 1 November. It begins the season of Allhallowtide,[64] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[65][66] Modern customs observed on Halloween have been influenced by American traditions and include trick or treating, wearing costumes and playing games.

Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween. Children go in masks and costumes[67] from house to house, asking for treats such as sweets or sometimes money, with the question, "Trick or treat?" The word "trick" implies a "threat" to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given.[67] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling.[68] John Pymm writes that "many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church."[69] These feast days included All Hallows' Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday.[70][71]

Souling

The practice of Souling originates in the medieval era of Christian Europe, in which soul cakes are given out to soulers (mainly consisting of children and the poor) who go from door to door during the days of Allhallowtide singing and saying prayers "for the souls of the givers and their friends".[72][73] The customs associated with Souling during Allhallowtide include or included consuming and/or distributing soul cakes, singing, carrying lanterns, dressing in disguise, bonfires, playing divination games, carrying a horse's head and performing plays. Souling is still practised in Cheshire and Sheffield.

In England, historically Halloween was associated with Souling which is a Christian practice carried out during Allhallowtide and Christmastide. The custom was popular in England and is still practised to a minor extent in Sheffield and Cheshire during Allhallowtide. According to Morton (2013), Souling was once performed throughout the British Isles and the earliest activity was reported in 1511.[74] However, by the end of the 19th century, the extent of the practice during Allhallowtide was limited to parts of England and Wales.

According to Gregory (2010), Souling involved a group of people visiting local farms and cottages. The merrymakers would sing a "traditional request for apples, ale, and soul cakes."[75] The songs were traditionally known as Souler's songs and were sung in a lamentable tone during the 1800s.[76] Sometimes adult soulers would use a musical instrument, such as a Concertina.[74]

Rogers (2003) believes Souling was traditionally practised in the counties of Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, peak district of Derbyshire, Somerset and Herefordshire.[77] However, Souling also was associated with other areas. Hutton (2001) believes Souling took place in Hertfordshire.[78] Palmer (1976) states that Souling took place on All Saints day in Warwickshire.[79] However, the custom of Souling ceased to be followed relatively early in the county of Warwickshire but the dole instituted by John Collet in Solihull (now within West Midlands) in 1565 was still being distributed in 1826 on All Souls day. The announcement for collection was made by ringing church bells.[80] Further, soul-cakes were still made in Warwickshire (and other parts of Yorkshire) even though no one visited for them.[78]

According to Brown (1992) Souling was performed in Birmingham and parts of the West Midlands;[81] and according to Raven (1965) the tradition was also kept in parts of the Black Country.[82] The prevalence of Souling was so localised in some parts of Staffordshire that it was observed in Penn but not in Bilston, both localities now in modern Wolverhampton.[83][84] In Staffordshire, the "custom of Souling was kept on All Saints' Eve" (Halloween).[85]

Similarly in Shropshire, during the late 19th century, "there was set upon the board at All Hallows Eve a high heap of Soul-cakes" for visitors to take.[86] The songs sung by people in Oswestry (Shropshire) contained some Welsh.[87]

St Clement's Day

St Clement's Day is celebrated on 23 November. Modern observances include a gathering of blacksmiths at the National Trust's Finch Foundry in Sticklepath "where they practise their art and celebrate their patron saint, St Clement".[88] Historically, the festival was celebrated in many parts of England and involved the playing of divination games with apples. The festival was known as Bite-Apple night in places such as Wednesbury (Sandwell) and Bilston (Wolverhampton)[89] when people went "Clementing" in a similar manner to Souling. The Clementing custom was also observed in Aston, Sutton Coldfield, Curdworth, Minworth and Kingsbury.[90] During the 19th century, St. Clement was a popular saint in West Bromwich and during the 1850s, children and others in neighbouring Oldbury also begged for apples on St. Clement's day and money on St. Thomas's day,[91] which takes place on 21 December. In Walsall, apples and nuts were provided by the local council on St. Clement's day.[92]

Bonfire Night

Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Day, Bonfire Night and Firework Night, is an annual commemoration observed on 5 November, primarily in the United Kingdom. Its history begins with the events of 5 November 1605, when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. Celebrating the fact that King James I had survived the attempt on his life, people lit bonfires around London; and months later, the introduction of the Observance of 5th November Act enforced an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot's failure. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events, centre on a bonfire and extravagant firework displays.

Lewes Bonfire describes a set of celebrations held in the town of Lewes, Sussex that constitute the United Kingdom's largest and most famous Bonfire Night festivities,[93] with Lewes being called the bonfire capital of the world.[94]

Always held on 5 November (unless the 5th falls on a Sunday,[95] in which case it's held on Saturday 4th), the event not only marks Guy Fawkes Night - the date of the uncovering of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 - but also commemorates the memory of the seventeen Protestant martyrs from the town burned at the stake for their faith[96] during the Marian Persecutions.

Christmas

.jpg.webp)

Christmas is an annual commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ,[97][98] observed on 25 December. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year, it is preceded by the season of Advent or the Nativity Fast and initiates the season of Christmastide, which historically in England lasts twelve days and culminates on Twelfth Night.[99]

Christmas decorations are put up in shops and town centres from early November. Many towns and cities have a public event involving a local or regional celebrity to mark the switching on of Christmas lights. Decorations in people's homes are commonly put up from early December, traditionally including a Christmas tree, cards, and lights both inside and outside the home. Every year, Norway donates a giant Christmas tree for the British to raise in Trafalgar Square as a thank you for helping during the Second World War. Christmas carolers at Trafalgar Square in London sing around the tree on various evenings up until Christmas Eve and Christmas decorations are traditionally left up until the evening of January 5 (the night before Epiphany); it is considered bad luck to have Christmas decorations up after this date. In practice, many Christmas traditions, such as the playing of Christmas music, largely stop after Christmas Day.[100]

Mince pies are traditionally sold during the festive season and are a popular food for Christmas.[101] Other traditions include hanging Advent calendars, holding the Nativity plays, giving presents and eating the traditional Christmas dinner. Boxing Day is a bank holiday, and if it happens to fall on a weekend then a special Bank Holiday Monday will occur. Other traditions include carol singing, sending Christmas cards, going to Church and watching the Christmas pantomime for children.

Father Christmas

Father Christmas is the traditional English name for the personification of Christmas. Although now known as a Christmas gift-bringer, and normally considered to be synonymous with American culture's Santa Claus which is now known worldwide, he was originally part of an unrelated and much older English folkloric tradition. The recognisably modern figure of the English Father Christmas developed in the late Victorian period, but Christmas had been personified for centuries before then.[103]

English personifications of Christmas were first recorded in the 15th century, with Father Christmas himself first appearing in the mid-17th century in the aftermath of the English Civil War. The Puritan-controlled English government had legislated to abolish Christmas, considering it papist, and had outlawed its traditional customs. Royalist political pamphleteers, linking the old traditions with their cause, adopted Old Father Christmas as the symbol of 'the good old days' of feasting and good cheer. Following the Restoration in 1660, Father Christmas's profile declined. His character was maintained during the late 18th and into the 19th century by the Christmas folk plays later known as mummers plays.

Until Victorian times, Father Christmas was concerned with adult feasting and merry-making. He had no particular connection with children, nor with the giving of presents, nocturnal visits, stockings or chimneys. But as later Victorian Christmases developed into child-centric family festivals, Father Christmas became a bringer of gifts. The popular American myth of Santa Claus arrived in England in the 1850s and Father Christmas started to take on Santa's attributes. By the 1880s the new customs had become established, with the nocturnal visitor sometimes being known as Santa Claus and sometimes as Father Christmas. He was often illustrated wearing a long red hooded gown trimmed with white fur.

Any residual distinctions between Father Christmas and Santa Claus largely faded away in the early years of the 20th century, and modern dictionaries consider the terms Father Christmas and Santa Claus to be synonymous.

See also

References

- ↑ Whistler, Laurence (5 October 2015). The English Festivals. Dean Street Press. ISBN 9781910570494 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Simpson, Jacqueline; Steve Roud (2000). "New Year". A dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-210019-X.

- ↑ Page, Michael; Robert Ingpen (1987). Encyclopedia of Things that Never Were. New York: Viking Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-670-81607-8.

- ↑ Newell, The Allendale Fire Festival

- 1 2 Hone, William (1826). The Every-Day Book. London: Hunt and Clarke. p. 71.

- 1 2 "Plough Monday". Oxford English Dictionary (online edition, subscription required). Archived from the original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ↑ Millington, Peter (1979). "Plough Monday Customs in England". Folk Play Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland. Master Mummers. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ "Photos of Plough Monday in England - Traditions and Customs". projectbritain.com.

- ↑ Chambers 21st Century Dictionary, Revised ed., Allied Publishers, 2005 ISBN 9780550142108

- ↑ Ansgar, 1986, Chaucer and the Cult of Saint valentine, pp. 46–58

- ↑ Cooper, J.C. (23 October 2013). Dictionary of Christianity. Routledge. p. 278. ISBN 9781134265466.

Valentine, St (d. c. 270, f.d. 14 February). A priest of Rome who was imprisoned for succouring persecuted Christians, he became a convert and, although he is supposed to have restored the sight of the jailer's blind daughter, he was clubbed to death in 269. His day is 14 February, as is that of St Valentine, bishop of Terni, who was martyred a few years later in 273.

- ↑ Ball, Ann (1 January 1992). A Litany of Saints. OSV. ISBN 9780879734602.

While in prison, he restored sight to the little blind daughter of his judge, Asterius, who thereupon was converted with all his family and suffered martyrdom with the saint.

- ↑ Guiley, Rosemary (2001). The Encyclopedia of Saints. Infobase Publishing. p. 341. ISBN 9781438130262.

On the morning of his execution, he supposedly sent a farewell message to the jailer's daughter, signed "from your Valentine." His body was buried on the Flaminian Way in Rome, and his relics were taken to the church of St. Praxedes.

- ↑ Leigh Eric Schmidt, "The Fashioning of a Modern Holiday: St. Valentine's Day, 1840–1870" Winterthur Portfolio 28.4 (Winter 1993), pp. 209–245.

- ↑ "St Valentine Key, Italy". Pitt Rivers Museum. University of Oxford. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

While Saint Valentine's keys are traditionally gifted as a romantic symbol and an invitation to unlock the giver's heart, Saint Valentine is also a patron saint of epilepsy. The belief that he could perform miraculous cures and heal the condition – also known as 'Saint Valentine's illness' or 'Saint Valentine's affliction' – was once common in southern Germany, eastern Switzerland, Austria, and northern Italy. To this day, a special ceremony where children are given small golden keys to ward off epilepsy is held at the Oratorio di San Giorgio, a small chapel in Monselice, Padua, on 14 February each year.

- ↑ "Holy Days". Church of England (Anglican Communion). 2012. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

February 14 Valentine, Martyr at Rome, c.269

- ↑ Pfatteicher, Philip H. (1 August 2008). New Book of Festivals and Commemorations: A Proposed Common Calendar of Saints. Fortress Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780800621285. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

IO February 14 The Lutheran Service Book, with its penchant for the old Roman calendar, commemorates Valentine on this date.

- ↑ Kyrou, Alexandros K. (14 February 2015). "The Historical and Orthodox Saint Valentine". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

The actual Orthodox liturgical Feast Days of Valentinos (Greek)/Valentinus (Latin) commemorate two Early Christian saints, Saint Valentine the Presbyter of Rome (July 6) and Hieromartyr Valentine the Bishop of Intermna (Terni), Italy (July 30).

- ↑ "British Folk Customs, Jack Valentine, Norfolk". information-britain.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Valentines Day Past and Present". Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ "The origin of pancake racing". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ Robert J. Myers, Hallmark Cards (1972), Celebrations; the complete book of American holidays, Doubleday, pp. 144–146

- ↑ "Interfaith holy days by faith". Religion & Ethics. BBC. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ↑ Bernard Trawicky, Ruth Wilhelme Gregory (2000). Anniversaries and Holidays. American Library Association. ISBN 9780838906958.

Easter is the central celebration of the Christian liturgical year. It is the oldest and most important Christian feast, celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. The date of Easter determines the dates of all movable feasts except those of Advent.

- ↑ Aveni, Anthony (2004). "The Easter/Passover Season: Connecting Time's Broken Circle", The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays. Oxford University Press. pp. 64–78. ISBN 0-19-517154-3.

- ↑ "UK bank holidays". gov.uk.

- 1 2 "The Origins of Popular Supersitions and Customs: Days and Seasons: (15) Hocktide--or Hoke Day". www.sacred-texts.com.

- ↑ Noted by George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991:365.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 556.

- ↑ "British Council | China". www.britishcouncil.cn. Archived from the original on 31 December 2007.

- ↑ McSmith, Andy (23 April 2009). "Who is St George?". The Independent. London. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ "How to celebrate St Georges Day – celebration event". Stgeorgesholiday.com. 6 November 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "School History of England". A.S. Barnes and Burr. 2 November 1862 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald (2001) Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820570-8

- ↑ Wright, Arthur Robinson (1940) British Calendar Customs: England, Vol. 3. (Folk-lore Society, Publications; vol. 106.) London: W. Glaisher, Limited

- ↑ Roud, Steve (2006) The English Year. Penguin Books

- ↑ Rodney P. Carlisle (2009) Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society, Volume 1. SAGE

- ↑ Caput XV: De mensibus Anglorum from De mensibus Anglorum. Available online: Archived 7 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Blumberg, Antonia (30 April 2015). "Beltane 2015: Facts, History And Traditions Of The May Day Festival". HuffPost. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ "Beltane". BBC. 7 June 2006. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ↑ Judge 2000, p. 21.

- ↑ Judge 2000, p. 24.

- 1 2 Judge 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ Judge 2000, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Judge 2000, p. 5.

- ↑ Judge 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Chambers 1879, pp. 693–694.

- ↑ Browning 1995, p. 54; House of Commons Journal 1802, pp. 49–50.

- 1 2 Vickery 2010, p. 166.

- ↑ "Restoration of the Monarchy". All Saints' Church Northampton. 29 May 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- 1 2 InfoBritain

- ↑ Hüsken 1996, p. 19

- ↑ Roud, Steve (31 January 2008). The English Year. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141919270 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Irvine, Theodora Ursula (1919). How to Pronounce the Names in Shakespeare: The Pronunciation of the Names in the Dramatis Personae of Each of Shakespeare's Plays, Also the Pronunciation and Explanation of Place Names and the Names of All Persons, Mythological Characters, Etc., Found in the Text, with Forewords by E.H. Sothern and Thomas W. Churchill and with a List of the Dramas Arranged Alphabetically Indicating the Pronunciation of the Names of the Characters in the Plays. Hinds, Hayden & Eldredge. p. 177.

Lammas or Lammas Day (August 1st) means the loaf-mass day. The day of first fruit offerings, when a loaf was given to the priests in lieu of the first-fruits.

- ↑ Melton, J. Gordon (2011 Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC Clio

- ↑ Gandolphy, Peter (1815). An Exposition of Liturgy. p. 51.

Thus Christ-Mass implies that season when the incarnation and birth of Christ, are commemorated in the Mass. In the same manner are formed Candle-Mass, Michaelmas, Lammas, &c. Lammas-day for instance, which falls on the 1st of August, is derived from the Saxon word Laf, a Loaf and Mæse, or Mass: It having been customary on that day to make an offering to the Church, of a loaf made of new corn.

- 1 2 Gellatly, Justin; Gellatly, Louise; Jones, Matthew (2017). Baking School. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-97878-8.

- ↑ T.C. Cokayne, ed. Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcarft (Rolls Series) vol. III:291, noted by George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991:371.

- ↑ Roy, Christian (2005) Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC CLIO

- ↑ Wilson, Marie-Claire (2011) Seasonal Awareness and Wellbeing: Looking and Feeling Better the Easy Way. John Hunt Publishing

- ↑ "Eastbourne Lammas Festival". www.lammasfest.org.

- ↑ "The Living Church". Morehouse-Gorham Company. 2 July 2001 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Tudor Hallowtide". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

Hallowtide covers the three days – 31 October (All-Hallows Eve or Hallowe'en), 1 November (All Saints) and 2 November (All Souls).

- ↑ Hughes, Rebekkah (29 October 2014). "Happy Hallowe'en Surrey!" (PDF). The Stag. University of Surrey. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Halloween or Hallowe'en, is the yearly celebration on October 31st that signifies the first day of Allhallowtide, being the time to remember the dead, including martyrs, saints and all faithful departed Christians.

- ↑ Don't Know Much About Mythology: Everything You Need to Know About the Greatest Stories in Human History but Never Learned (Davis), HarperCollins, p. 231

- 1 2 "Halloween". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ↑ Faces Around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia of the Human Face (Margo DeMello), ABC-CLIO, p. 225

- ↑ A Student's Guide to A2 Performance Studies for the OCR Specification (John Pymm), Rhinegold Publishing Ltd, p. 28

- ↑ Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art, Volume 1 (Thomas Green), ABC-CLIO p. 566

- ↑ Interacting communities: studies on some aspects of migration and urban ethnology (Zsuzsa Szarvas), Hungarian Ethnographic Society, p. 314

- ↑ Mary Mapes Dodge, ed. (1883). St. Nicholas Magazine. Scribner & Company. p. 93.

Soul-cakes," which the rich gave to the poor at the Halloween season, in return for which the recipients prayed for the souls of the givers and their friends. And this custom became so favored in popular esteem that, for a long time, it was a regular observance in the country towns of England for small companies to go from parish to parish, begging soul-cakes by singing under the windows some such verse as this: "Soul, souls, for a soul-cake; Pray you good mistress, a soul-cake!

- ↑ Carmichael, Sherman (2012). Legends and Lore of South Carolina. The History Press. p. 70. ISBN 9781609497484.

The practice of dressing up and going door to door for treats dates back to the middle ages and the practice of souling.

- 1 2 Morton, Lisa (2013) Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books

- ↑ Gregory, David (2010) The Late Victorian Folksong Revival: The Persistence of English Melody, 1878-1903 Scarecrow Press

- ↑ Fleische (1826) An Appendix to His Dramatic Works. Contents: the Life of the Author by Aus. Skottowe, His Miscellaneous Poems; a Critical Glossary, Comp. After Mares, Drake, Ayscough, Hazlitt, Douce and Others

- ↑ Rogers, Nicholas (2003) Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Hutton, Ronald (2001) Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. OUP Oxford

- ↑ Palmer, Roy (1976) The folklore of Warwickshire, Volume 1976, Part 2 Batsford

- ↑ Society, Dugdale (2 November 2007). Dugdale Society Occasional Papers. Dugdale Society. ISBN 9780852200896 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Brown, Richard (1992)The Folklore, Superstitions and Legends of Birmingham and the West Midlands. Westwood Press Publications

- ↑ Raven, Michael (1965)Folklore and Songs of the Black Country, Volume 1. Wolverhampton Folk Song Club

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph; Nutt, Alfred Trübner; Wright, Arthur Robinson; Crooke, William (2 November 1914). "Folklore". Folklore Society – via Google Books.

- ↑ Publications, Volume 106. W. Glaisher, Limited, 1940. The tradition was noted in 1892 to be held in Penn which is now in Wolverhampton, West Midlands.

- ↑ Britain), Folklore Society (Great (2 November 1940). "Publications". W. Glaisher, Limited – via Google Books.

- ↑ Walsh, William Shepard (1898) Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities. Gale Research Company

- ↑ The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, Volume 62 (1886) J. W. Parker and Son

- ↑ Sarah Pitt (30.11.2018) Oakhampton Today. Blacksmiths gather for St Clement's Day at Finch Foundry in Sticklepath

- ↑ Hackwood, Frederick William (1974) Staffordshire customs, superstitions & folklore. EP Publishing

- ↑ Society, Dugdale (2 November 2007). Dugdale Society Occasional Papers. Dugdale Society. ISBN 9780852200896 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Hackwood, Frederick William (1974) Staffordshire customs, superstitions & folklore. EP Publishing

- ↑ Britain), Folklore Society (Great (2 November 1896). "Publications" – via Google Books.

- ↑ Times Writers (5 November 2009). "Tonight's the night: bonfires and fireworks". Times. London.

- ↑ Jones, Lucy (2 November 2010). "Unusual places to go and watch fireworks". London: The Daily Telegraph.

They don't call Lewes the Bonfire capital of the world for nothing.

- ↑ "The Lewes Societies". Lewes Bonfire Council. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ↑ Lewes Bonfire 2018: the details you need to know. (3.11.18) Sussex Express.

- ↑ Christmas, Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

Archived 2009-10-31. - ↑ Martindale, Cyril Charles."Christmas". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.

- ↑ Forbes, Bruce David (1 October 2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-520-25802-0.

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide.

On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on 5 January, the eve of Epiphany. If 26 December, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on 6 January, the evening of Epiphany itself.

After Christmas and Epiphany were in place, on 25 December and 6 January, with the twelve days of Christmas in between, Christians slowly adopted a period called Advent, as a time of spiritual preparation leading up to Christmas. - ↑ "British Christmas: introduction, food, customs". Woodlands-Junior.Kent.sch.uk. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014.

- ↑ "Christmas dinner". Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Roud, Steve (2006). The English Year. London: Penguin Books. pp. 385–387. ISBN 978-0-140-51554-1.

Works cited

- Browning, Andrew (1995). English Historical Documents. Volume 6: 1660–1714 (2nd ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14371-4.

- Chambers, Robert (1879). The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers.

- House of Commons Journal. Volume 8: 30 May 1660. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1802. Retrieved 3 November 2017 – via British History Online.

- Hüsken, Wim N. M (1996). "Rushbearing:a forgotten British custom". English parish drama. Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-0060-0.

- Judge, Roy (2000). The Jack-in-the-Green: A May Day Custom (second ed.). London: The Folklore Society Books. ISBN 0-903515-20-2.

- Vickery, Roy (2010). Garlands, Conkers and Mother-Die: British and Irish Plant-Lore. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-0195-2.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hock-tide". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 556.