Plough Monday is the traditional start of the English agricultural year. While local practices may vary, Plough Monday is generally the first Monday after Epiphany, 6 January.[1][2] References to Plough Monday date back to the late 15th century.[2] The day before Plough Monday is referred to as Plough Sunday, in which a ploughshare is brought into the local Christian church (such as the Catholic, Lutheran, and Anglican traditions) with prayers for the blessing of human labour, tools, as well as the land.[3][4]

History

The day traditionally saw the resumption of work after the Christmas period in some areas, particularly in northern England and East England.[6] The customs observed on Plough Monday varied by region, but a common feature to a lesser or greater extent was for a plough to be hauled from house to house in a procession, collecting money. They were often accompanied by musicians, an old woman or a boy dressed as an old woman, called the "Bessy," and a man in the role of the "fool." 'Plough Pudding' is a boiled suet pudding, containing meat and onions. It is from Norfolk and is eaten on Plough Monday.[1]

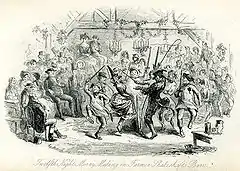

William Hone made use of Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain: Including the Whole of Mr. Bourne's Antiquitates Vulgares (1777) by the antiquary John Brand. Brand's work (with additions by Henry Ellis) mentions a northern English Plough Monday custom also observed in the beginning of Lent. Evidently the Plough dance depicted by Phiz in his illustrations for Harrison Ainsworth's 1858 novel Mervyn Clitheroe, and Ainsworth's description, is based on this or a similar account:[7]

The FOOL PLOUGH goes about: a pageant consisting of a number of sword dancers dragging a plough, with music; one, sometimes two, in very strange attire; the Bessy, in the grotesque habit of an old woman, and the Fool, almost covered with skins, a hairy cap on, and the tail of some animal hanging from his back. The office of one of these characters, in which he is very assiduous, is to go about rattling a box amongst the spectators of the dance, in which he receives their little donations.[8]

In the Isles of Scilly, locals would cross-dress and then visit their neighbours to joke about local occurrences. There would be guise dancing (folk-etymologically rendered as "goose dancing" by either the authors or those whom they observed) and considerable drinking and revelry.[9]

Modern observances

Plough Monday customs declined in the 19th century but were revived in some towns in the 20th.[10] They are now mainly associated with Molly dancing and a good example can be seen each year at Maldon in Essex. Livery Companies in the City of London, notably the Worshipful Company of Feltmakers hold a traditional banquet with a medieval sung grace, with the response from those gathered of 'God speed the plough'.

Whittlesey Straw Bear festival

Instead of pulling a decorated plough, during the 19th century, men or boys would dress in a layer of straw and were known as Straw Bears who begged door to door for money. The tradition is maintained annually in January in Whittlesey, near Peterborough, where on the preceding Saturday, "the Straw Bear is paraded through the streets of Whittlesey".[11]

Goathland Plough Stots

Based in Goathland, North Yorkshire, on every Plough Monday, the troop perform a Long Sword dance.[12]

In other countries

In certain regions of Belgium, the Monday after the Epiphany is called Verloren Maandag (literally lost Monday, indicating a day with no work and hence no pay) with typical food associated.[13]

See also

- Royal Ploughing Ceremony in Southeast Asia

- Pluguşorul

References

- 1 2 Hone, William (1826). The Every-Day Book. London: Hunt and Clarke. p. 71.

- 1 2 "Plough Monday". Oxford English Dictionary (online edition, subscription required). Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- ↑ "After Epiphany, the Twelfth Night of Christmas". St. Andrew Lutheran Church. 9 January 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

Sunday celebrations usually involved bringing a ploughshare into a church with prayers for the blessing of the land.

- ↑ Nicholls, Janet (2006). "Plough Sunday" (PDF). Diocese of Chelmsford. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ↑ Jo Draper (January 2010). "Plough Monday in Dorchester". Dorset Life Magazine. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ Millington, Peter (1979). "Plough Monday Customs in England". Folk Play Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland. Master Mummers. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ "Hone's Every-Day Book". The material is omitted from the Plough Monday entry in the Revised edition of Brand of 1905.

- ↑ John Brand, Observations on Popular Antiquities (1777). Loc. in new edition with the additions of Sir Henry Ellis (Chatto and Windus, London 1900), p. 273-274.

- ↑ "Plough Monday", The Every-day Book and Table Book; or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Sports, Pastimes, Ceremonies, Manners, Customs, and Events, Each of the Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Days, in Past and Present Times; Forming a Complete History of the Year, Months, and Seasons, and a Perpetual Key to the Almanac, Including Accounts of the Weather, Rules for Health and Conduct, Remarkable and Important Anecdotes, Facts, and Notices, in Chronology, Antiquities, Topography, Biography, Natural History, Art, Science, and General Literature; Derived from the Most Authentic Sources, and Valuable Original Communication, with Poetical Elucidations, for Daily Use and Diversion. Vol III., ed. William Hone, (London: 1838) p 81. Retrieved on 6 June 2008

- ↑ "The English Tradition of Plough Monday". churchmousec.wordpress.com. 8 January 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ↑ Project Britain

- ↑ Lloyd, Chris (6 January 2009). "Are the bells tolling for a great English tradition?". The Northern Echo. p. 3. ISSN 2043-0442.

- ↑ nl:Verloren maandag