Food in ancient Rome reflects both the variety of food-stuffs available through the expanded trade networks of the Roman Empire and the traditions of conviviality from ancient Rome's earliest times, inherited in part from the Greeks and Etruscans. In contrast to the Greek symposium, which was primarily a drinking party, the equivalent social institution of the Roman convivium (dinner party) was focused on food. Banqueting played a major role in Rome's communal religion. Maintaining the food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, and continued to be one of the main ways the emperor expressed his relationship to the Roman people and established his role as a benefactor. Roman food vendors and farmers' markets sold meats, fish, cheeses, produce, olive oil and spices; and pubs, bars, inns and food stalls sold prepared food.

Bread was an important part of the Roman diet, with more well-to-do people eating wheat bread and poorer people eating that made from barley. Fresh produce such as vegetables and legumes were important to Romans, as farming was a valued activity. A variety of olives and nuts were eaten. While there were prominent Romans who discouraged meat eating, a variety of meat products were prepared, including blood puddings, sausages, cured ham and bacon. The milk of goats or sheep was thought superior to that of cows; milk was used to make many types of cheese, as this was a way of storing and trading milk products. While olive oil was fundamental to Roman cooking, butter was viewed as an undesirable Gallic foodstuff. Sweet foods such as pastries typically used honey and wine-must syrup as a sweetener. A variety of dried fruits (figs, dates and plums) and fresh berries were also eaten.

Salt, which in its pure form was an expensive commodity in Rome, was the fundamental seasoning and the most common salty condiment was a fermented fish sauce known as garum. Locally available seasonings included garden herbs, cumin, coriander, and juniper berries. Imported spices included pepper, saffron, cinnamon, and fennel. While wine was an important beverage, Romans looked down on drinking to excess and drank their wine mixed with water; drinking wine "straight" was viewed as a barbarian custom.

Food

The main Roman ingredients in dishes were wheat, wine, meat and fish, bread, and sauces and spices. The richer Romans had luxurious lives, and sometimes hosted banquets or feasts.

Grains and legumes

Most people would have consumed at least 70 percent of their daily calories in the form of cereals and legumes.[1] Grains included several varieties of wheat—emmer, rivet wheat, einkorn, spelt, and common wheat (Triticum aestivum)[2]—as well as the less desirable barley, millet, and oats.[1]

Legumes included the lentil, chickpea, bitter vetch, broad bean, garden pea, and grass pea; Pliny names varieties such as the Venus pea,[3] and poets praise Egyptian lentils imported from Pelusium.[4] Legumes were planted in rotation with cereals to enrich the soil,[5] and were stockpiled in case of famine. The agricultural writer Columella gives detailed instructions on curing lentils, and Pliny says they had health benefits.[6] Although usually thought of as modest fare, legumes also appear among the dishes at banquets.[7]

Puls (pottage)[8] was considered the aboriginal food of the Romans, and played a role in some archaic religious rituals that continued to be observed during the Empire.[9] The basic grain pottage could be elaborated with chopped vegetables, bits of meat, cheese, or herbs to produce dishes similar to polenta or risotto.[10] "Julian stew" (Pultes Iulianae) was made from spelt to which was added two kinds of ground meat, pepper, lovage, fennel, hard bread, and a wine reduction; according to tradition, it was eaten by the soldiers of Julius Caesar and was a "quintessential Roman dish."[11]

_on_Vicolo_Storto_(Reg_VII%252C_Ins_2%252C_22)_belonging_to_N._Popidius_Priscus%252C_Pompeii_(14856682197).jpg.webp)

Urban populations and the military preferred to consume their grain in the form of bread.[1] The lower classes ate coarse brown bread made from emmer or barley. Fine white loaves were leavened by wild yeasts and sourdough cultures.[12] The beer-drinking Celts of Spain and Gaul were known for the quality of their breads risen with barm or brewers' yeast.[13] The poem Moretum describes a "ploughman's lunch", a flatbread prepared on a griddle and topped with cheese and a pesto-like preparation, somewhat similar to pizza or focaccia.[14]

Maintaining a bread oven is labor-intensive and requires space, so apartment dwellers probably prepared their dough at home, then had it baked in a communal oven.[15] Mills and commercial ovens, usually combined in a bakery complex, were considered so vital to the wellbeing of Rome that several religious festivals honored the deities who furthered these processes—and even the donkeys who toiled in the mills. Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, was seen as complementary to Ceres, the goddess of grain, and donkeys were garlanded and given a rest on the Festival of Vesta. The Fornacalia was the "Festival of Ovens". Lateranus was a deity of brick ovens.

Other produce

Because of the importance of landowning in the formation of the Roman cultural elite, Romans idealized farming and took a great deal of pride in serving produce. Leafy greens and herbs were eaten as salads with vinegar dressings.[16] Cooked vegetables such as beets, leeks, and gourds were prepared with sauces as first courses or served with bread as a simple meal.[16] The Romans had over 20 kind of vegetables and greens. Cured olives were available in wide variety even to those on a limited budget.[16] Truffles and wild mushrooms, while not everyday fare, were perhaps more commonly foraged than today.[17]

Provinces exported regional dried fruits such as Carian figs and Theban dates,[16] and fruit trees from the East were propagated throughout the Western empire: the cherry from Pontus (present-day Turkey); peach (persica) from Persia (Iran), along with the lemon and other citrus; the apricot from Armenia; the "Damascan" or damson plum from Syria; and what the Romans called the "Punic apple", the pomegranate from North Africa.[18] The Romans ate cherries, blackberries, currants, elderberries, dates, pomegranates, peaches, apricots, quinces, melons, plums, figs, grapes, apples and pears.[19]

Berries were cultivated or gathered wild. Familiar nuts included almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, pistachios, pine nuts, and chestnuts.[20] Fruit and nut trees could be grafted with multiple varieties.[21]

Meat and dairy

While there were prominent Romans who discouraged meat eating– the Emperors Didius Julianus and Septimius Severus disdained meat[22]–Roman butchers sold a variety of fresh meats, including pork, beef, and mutton or lamb.[23] Due to the lack of refrigeration, techniques of preservation for meat, fish, and dairy were developed. No portion of the animal was allowed to go to waste, resulting in blood puddings, meatballs (isicia), sausages, and stews.[23] Rural people cured ham and bacon, and regional specialties such as the fine salted hams of Gaul were items of trade.[23] The sausages of Lucania were made from a mixture of ground meats, herbs, and nuts, with eggs as a binding ingredient, and then aged in a smoker.[24]

Fresh milk was used in medicinal and cosmetic preparations, or for cooking.[25] The milk of goats or sheep was thought superior to that of cows.[26] Cheese was easier to store and transport to market; literary sources describe cheesemaking in detail, including fresh and hard cheeses, regional specialties, and smoked cheeses.[27]

Oils and fat

Olive oil was fundamental not only to cooking, but to the Roman way of life, as it was used also in lamps and preparations for bathing and grooming.[28] The Romans invented the trapetum for extracting olive oil.[29] The olive orchards of Roman Africa attracted major investment and were highly productive, with trees larger than those of Mediterranean Europe; massive lever presses were developed for efficient extraction.[30] Spain was also a major exporter of olive oil, but the Romans regarded oil from central Italy as the finest.[31] Specialty blends were created from Spanish olive oil; Liburnian Oil (Oleum Liburnicum) was flavored with elecampane, cyperus root, bay laurel and salt.[24]

Butter was mostly disdained by the Romans, but was a distinguishing feature of the Gallic diet.[32] Lard was used for baking pastries and seasoning some dishes.[23]

Seasonings and sweeteners

Salt was the fundamental seasoning: Pliny the Elder remarked that "Civilized life cannot proceed without salt: it is so necessary an ingredient that it has become a metaphor for intense mental pleasure."[33] In Latin literature, salt (sal) was a synonym for "wit".[34] It was an important item of trade, but pure salt was relatively expensive. The most common salty condiment was garum, the fermented fish sauce that added the flavor dimension now called "umami". Major exporters of garum were located in the provinces of Spain.

Locally available seasonings included garden herbs, cumin, coriander, and juniper berries.[23] Pepper was so vital to the cuisine that ornamental pots (piperatoria) were created to hold it. Piper longum was imported from India, as was spikenard, used to season game birds and sea urchins.[35]

Other imported spices were saffron, cinnamon, and the silphium of Cyrene, a type of pungent fennel that was over-harvested into extinction during the reign of Nero, after which time it was replaced with laserpicium, asafoetida exported from present-day Afghanistan.[36] Pliny estimated that Romans spent 100 million sesterces a year on spices and perfumes from India, China, and the Arabian peninsula.[37]

Sweeteners were limited mostly to honey and wine-must syrup (defrutum).[23] Cane sugar was an exotic ingredient used as a garnish or flavoring agent, or in medicines.[23]

Agriculture and markets

The central government took an active interest in supporting agriculture.[39] Producing food was the top priority of land use.[40] Larger farms (latifundia) achieved an economy of scale that sustained urban life and its more specialized division of labor.[39] The Empire's transportation network of roads and shipping lines benefitted small farmers by opening up access to local and regional markets in towns and trade centers. Agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and selective breeding were disseminated throughout the Empire, and new crops were introduced from one province to another, such as peas and cabbage to Britain.[41]

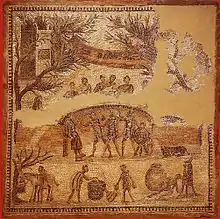

Food vendors are depicted in art throughout the Empire. In the city of Rome, the Forum Holitorium was an ancient farmers' market, and the Vicus Tuscus was famous for its fresh produce.[42] Throughout the city, meats, fish, cheeses, produce, olive oil, spices, and the ubiquitous condiment garum (fish sauce) were sold at macella, Roman indoor markets, and at marketplaces throughout the provinces.[43]

Annona

Maintaining an affordable food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, when the state began to provide a grain dole (annona) to citizens who registered for it.[39] About 200,000–250,000 adult males in Rome received the dole, amounting to about 33 kg per month, for a per annum total of about 100,000 tonnes of wheat primarily from Sicily, Northern Africa, and Egypt.[44]

The dole cost at least 34 percent of state revenues,[39] but improved living conditions and family life among the lower classes,[45] and subsidized the rich by allowing workers to spend more of their earnings on the wine and olive oil produced on the estates of the landowning class.[39]

The grain dole also had symbolic value: it affirmed both the emperor's position as universal benefactor, and the right of all citizens to share in "the fruits of conquest".[39] The annona, public facilities, and spectacular entertainments mitigated the otherwise dreary living conditions of lower-class Romans, and kept social unrest in check. The satirist Juvenal, however, saw "bread and circuses" (panem et circenses) as emblematic of the loss of republican political liberty:[46]

The public has long since cast off its cares: the people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions and all else, now meddles no more and longs eagerly for just two things: bread and circuses.[47]

Romans who received the dole took it to a mill to have it ground into flour.[48] By the reign of Aurelian, the state had begun to distribute the annona as a daily ration of bread baked in state factories, and added olive oil, wine, and pork to the dole.[49]

Commercial food preparation

.jpg.webp)

Most people in the city of Rome lived in apartment buildings (insulae) that lacked kitchens, though shared cooking facilities might be available in ground-level commons areas. A charcoal brazier could be used for rudimentary cookery such as grilling and stewing in a pot (olla), but ventilation was poor and braziers were fire hazards.[51]

Prepared food was sold at pubs and bars, inns, and food stalls (tabernae, cauponae, popinae).[52] Some establishments had countertops fitted with openings for pots that may have kept food warm over a heat source (thermopolium) or simply served as storage vessels (dolia).[53]

Carryout and restaurant dining were for the lower classes. Frequenting taverns, where prostitutes sometimes worked, was among the moral failings that louche emperors and other public figures might be accused of.[54]

Mills and commercial ovens were usually combined in a bakery complex.[15]

Dietary theories

The importance of a good diet to health was recognized by medical writers such as Galen (2nd century AD), whose treatises included one On Barley Soup. Views on nutrition were influenced by schools of thought such as humoral theory.[55] Digestion of food within the body was thought to be a process analogous to cooking.[56]

Menus and recipes

The Latin expression for a full-course dinner was ab ovo usque ad mala, "from the egg to the apples," equivalent to the English "from soup to nuts."[57] A multicourse dinner began with the gustatio ("tasting" or "appetizer"), often a salad or other minimally cooked composed dish, with ingredients to promote good digestion. The cena proper centered on meat, a practice that evokes the tradition of communal banquets following animal sacrifice. A meal concluded with fruits and nuts, or with deliberately superfluous desserts (secundae mensae).[58]

Roman literature focuses on the dining habits of the upper classes,[59] and the most famous description of a Roman meal is probably Trimalchio's dinner party in the Satyricon, a fictional extravaganza that bears little resemblance to reality even among the most wealthy.[60] The poet Martial describes serving a more plausible dinner, beginning with the gustatio, which was a composed salad of mallow leaves, lettuce, chopped leeks, mint, arugula, mackerel garnished with rue, sliced eggs, and marinated sow udder. The main course was succulent cuts of kid, beans, greens, a chicken, and leftover ham, followed by a dessert of fresh fruit and vintage wine.[61]

A Roman recipe:

Parthian ChickenSpatchcock a chicken. Crush pepper, lovage, and a dash of caraway; blend in fish sauce to create a slurry, then thin with wine. Pour over chicken in a casserole with a lid. Dissolve asafoetida in warm water and baste chicken as it cooks. Season with pepper to serve.

Apicius, De Re Coquinaria 6.9.2[62]

Roman books on agriculture include a few recipes.[63] A book-length collection of Roman recipes is attributed to Apicius, a name for several figures in antiquity that became synonymous with "gourmet":[64] "the recipes are written haphazardly, as if someone familiar with the workings of a kitchen was jotting down notes for a colleague."[65] Although often imprecise, particularly with measurements, Apicius uses eight different verbs for techniques for incorporating eggs into a dish, including one that might produce a soufflé.[66]

Recipes include regional specialties such as Ofellas Ostiensis, an hors d'oeuvre made from "choice squares of marinated pork cooked in a spicy sauce of typically Roman flavors: lovage, fennel, cumin, and anise."[67] The signature dish Patina Apiciana required a complex forcemeat layered with egg and crepes, to be presented on a silver platter.[68]

Roman "foodies" indulged in wild game, fowl such as peacock and flamingo, large fish (mullet was especially prized), and shellfish. Oysters were farmed at Baiae, a resort town on the Campanian coast[23] known for a regional shellfish stew made from oysters, mussels, sea urchins, celery and coriander.[67]

The most spectacular dish of the emperor Vitellius was supposed to be the "Shield of Minerva", composed of pike liver, brains of pheasant and peacock, flamingo tongue, and lamprey milt. The description given by Suetonius emphasizes that these luxury ingredients were brought by the fleet from the far reaches of empire, from the Parthian frontier to the Straits of Gibraltar.[69] The Augustan historian Livy explicitly links the development of gourmet cuisine to Roman territorial expansion, dating the introduction of the first chefs to 187 BC, following the Galatian War.[70]

Wine and fermented beverages

Although food shortages were a constant concern, Italian viticulture produced an abundance of cheap wine that was shipped to Rome.[71] Most provinces were capable of producing wine, but regional varietals were desirable, and wine was a central item of trade. Shortages of vin ordinaire were rare.[72] Regional varieties such as Alban, Caecuban, and Falernian were prized.[37] Opimian was the most prestigious vintage.[73]

The major suppliers for the city of Rome were the west coast of Italy, southern Gaul, the Tarraconensis region of Spain, and Crete. Alexandria, the second-largest city in the Empire, imported wine from Laodicea in Syria and the Aegean.[74] At the retail level, taverns or specialty wine shops (vinaria) sold wine by the jug for carryout and by the drink on premises, with price ranges reflecting quality.[75]

In addition to regular consumption with meals, wine was a part of everyday religious observances. Before a meal, a libation was offered to the household gods. When Romans made their regular visits to burial sites to care for the dead, they poured a libation, facilitated at some tombs with a feeding tube into the grave.

Romans drank their wine mixed with water, or in "mixed drinks" with flavorings. Mulsum was a mulled sweet wine, and apsinthium was a wormwood-flavored forerunner of absinthe.[37] Although wine was enjoyed regularly, and the Augustan poet Horace coined the expression "truth in wine" (in vino veritas), drunkenness was disparaged. It was a Roman stereotype that Gauls had an excessive love of wine, and drinking wine "straight" (purum or merum, unmixed) was a mark of the "barbarian". The Gauls also brewed various forms of beer.

Dining at home

Since restaurants catered to the lower classes, fine dining could be sought only at private dinner parties in well-to-do houses, or at banquets hosted by social clubs (collegia).[76] The private home (domus) of an elite family would have had a kitchen, a kitchen garden, and a trained staff with a chef (archimagirus), a sous chef (vicarius supra cocos), and kitchen assistants (coci, singular cocus or coquus, from which the English "cook" derives).[77]

In upperclass households, the evening meal (cena) had important social functions.[78] Guests were entertained in a finely decorated dining room (triclinium), often with a view of the peristyle garden. Diners lounged on couches, leaning on the left elbow. The ideal number of guests for a dinner party (convivium, "life-sharing" or "a living together") was nine.[78]

By the late Republic, if not earlier, women dined, reclined, and drank wine along with men.[79] On at least some occasions, children attended, so they could acquire social skills.[80] Multicourse meals were served by the household slaves, who appear prominently in the art of late antiquity as images of hospitality and luxury.[81]

Feeding the military

One of the chief logistical concerns of the Roman military was feeding the men, cavalry horses, and pack animals, usually mules. Wheat and barley were the primary food sources. Meat, olive oil, wine, and vinegar were also provided. An army of 40,000, including soldiers and other personnel such as slaves, would have about 4,000 horses and 3,500 pack animals. An army of this size would consume about 60 tonnes of grain and 240 amphorae of wine and olive oil each day.

Each man received a ration of about 830 grams (1.8 lb) of wheat per day in the form of unmilled grain, which is less perishable than flour. Handmills were used to grind it. The supply of all these foodstuffs depended on availability, and was hard to guarantee during times of war or other adverse conditions. The military attracted sutlers who sold various items, including foodstuffs with which the soldier might supplement his diet.[82]

During the expansionism of the Republic, the army usually had combined living off the land and organized supply lines (the frumentatio) to ensure its food supply.[83] Under the Empire, provinces might pay in-kind taxes in the form of grain to provision the permanent garrisons.[83]

Cultural values

Refined cuisine could be moralized as a sign of either civilized progress or decadent decline.[84] The early Imperial historian Tacitus contrasted the indulgent luxuries of the Roman table in his day with the simplicity of the Germanic diet of fresh wild meat, foraged fruit, and cheese, unadulterated by imported seasonings and elaborate sauces.[85]

Because of the importance of landowning in Roman culture, produce—cereals, legumes, vegetables, and fruit—was most often considered a more civilized form of food than meat. The Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus, a vegetarian, regarded meat-eaters as not only less civilized but "slower in intellect."[86]

"Barbarians" might be stereotyped as ravenous carnivores.[87] The Historia Augusta describes the emperors Didius Julianus and Septimius Severus as disdaining meat in favor of vegetables, while the first emperor born of two barbarian parents, Maximinus Thrax, is said to have devoured mounds of meat.[22]

For Pliny, the making of pastries was a sign of civilized countries at peace.[88] The Mediterranean staples of bread, wine, and oil were sacralized by Roman Christianity, while Germanic meat consumption became a mark of paganism,[22] as it might be the product of animal sacrifice.

Some philosophers and Christians resisted the demands of the body and the pleasures of food, and adopted fasting as an ideal.[89] Food became simpler in general as urban life in the West diminished, trade routes were disrupted,[90] and the rich retreated to the more limited self-sufficiency of their country estates.[29] As an urban lifestyle came to be associated with decadence, the Church formally discouraged gluttony,[29] and hunting and pastoralism were seen as simple but virtuous ways of life.[91]

Further reading

- Emily Gowers The Loaded Table: Representations of Food in Roman Literature (Oxford University Press, 1993)

References

- 1 2 3 Peter Garnsey, "The Land," in Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire A.D. 70–192 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), vol. 11, p. 681.

- ↑ "Foodstuffs," in Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World (Harvard University Press, 1999), pp. 453–454.

- ↑ Flint-Hamilton, "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome," p. 373; Edwards, "Philology and Cuisine in De Re Coquinaria," p. 257.

- ↑ Vergil, Georgics 1.228; Martial 13.9.1; Ausonius 12.9.9; H.H. Huxley, Virgil: Georgics I and IV (Fletcher and Sons, 1963, 1967), p. 96.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 18.134, 137; Flint-Hamilton, "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome," p. 373.

- ↑ Columella, De Re Rustica 2.10.5–16; Pliny, Natural History 22.142; Flint-Hamilton, "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome," pp. 374–376.

- ↑ Flint-Hamilton, "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome," p. 382; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 198.

- ↑ Greg Woolf (2007). Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art. Barnes & Noble. p. 388. ISBN 978-1-4351-0121-0.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 19.83–84; Emily Gowers, The Loaded Table: Representation of Food in Roman Literature (Oxford University Press, 1993, 2003), p. 17; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 198.

- ↑ Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City, p. 144.

- ↑ John Edwards, "Philology and Cuisine in De Re Coquinaria," American Journal of Philology 122.2 (2001), pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Kimberly B. Flint-Hamilton, "Legumes in Ancient Greece and Rome: Food, Medicine, or Poison?" Hesperia 68.3 (1999), p. 371; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 18.68; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 198.

- ↑ Carol Field, The Italian Baker: The Classic Tastes of the Italian Countryside (Random House, 1985, 2011), p. 250.

- 1 2 Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, pp. 134–135.

- 1 2 3 4 Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 198.

- ↑ Faas, Patrick (2005). Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome, pp. 236-239. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Patrick Bowe, Gardens of the Roman World p. 49; Phyllis Pray Bober, Art, Culture, and Cuisine: Ancient and Medieval Gastronomy (University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 337; C. Srinivasan, Isabel M.G. Padilla, and Ralph Scorza, "Prunus spp. Almond, Apricot, Cherry, Nectarine, Peach and Plum," in Biotechnology of Fruit and Nut Crops (CABI Publishing, 2005), p. 512; Robert E.A. Palmer, Rome and Carthage at Peace (Franz Steiner, 1997), pp. 40, 45–46 (on the pomegranate).

- ↑ Around the Roman Table, p. 239.

- ↑ Faas (2005), p. 239.

- ↑ According to Pliny, Natural History; Bowe, Gardens of the Roman World, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 Montanari, "Romans, Barbarians, Christians," p. 166.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 199.

- 1 2 Edwards, "Philology and Cuisine in De Re Coquinaria," p. 259.

- ↑ Joan P. Alcock, "Milk and Its Products in Ancient Rome," in Milk: Beyond the Dairy. Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1999 (Prospect Books, 2000) pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Alcock, "Milk and Its Products in Ancient Rome," pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Alcock, "Milk and Its Products in Ancient Rome," pp. 35–37; Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, p. 150.

- ↑ Andrew Dalby, entry on olive oil, Food in the Ancient World A to Z (Routledge, 2003), p. 239.

- 1 2 3 "Foodstuff," in Late Antiquity, p. 455.

- ↑ David J. Mattingly, "Regional Variation in Roman Oleoculture: Some Problems of Comparability," in Landuse in the Roman Empire («L'Erma» di Bretschneider, 1994), pp. 91–93, 104.

- ↑ Dalby, Food in the Ancient World A to Z p. 239.

- ↑ Alcock, "Milk and Its Products in Ancient Rome," p. 33.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 31.88, as cited by Gower, The Loaded Table, p. 232.

- ↑ Gower, The Loaded Table, p. 232, citing especially Horace, Epistle 2.2.60.

- ↑ Edwards, "Philology and Cuisine in De Re Coquinaria," pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 19.39; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 199–200.

- 1 2 3 Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 200.

- ↑ J. Carson Webster, The Labors of the Months in Antique and Mediaeval Art to the End of the Twelfth Century, Studies in the Humanities 4 (Northwestern University Press, 1938), p. 128. In the collections of the Hermitage Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hopkins, "The Political Economy of the Roman Empire," p. 191.

- ↑ Peter Garnsey, "The Land," in The Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire A.D. 70–192 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), vol. 11, p. 679.

- ↑ Hopkins, "The Political Economy of the Roman Empire," pp. 195–196.

- ↑ J. Mira Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 198; Robert E.A. Palmer, Rome and Carthage at Peace (Steiner, 1997), p. 115, citing Varro, De Lingua Latina 5.146–147, on the Forum Holitorium as a macellum.

- ↑ Claire Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate (Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 207–208 et passim; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," p. 198, and "Cooks and Cookbooks," p. 299, in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 299.

- ↑ Hopkins, "The Political Economy of the Roman Empire," p. 191, reckoning that the surplus of wheat from the province of Egypt alone could meet and exceed the needs of the city of Rome and the provincial armies.

- ↑ Wiseman, T. P. (1969). "The Census in the First Century B.C". Journal of Roman Studies. 59 (1/2): 59–75. doi:10.2307/299848. JSTOR 299848. S2CID 163672978., p. 73.

- ↑ Catherine Keane, Figuring Genre in Roman Satire (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 36; Eckhart Köhne, "Bread and Circuses: The Politics of Entertainment," in Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome (University of California Press, 2000), p. 8.

- ↑ Juvenal, Satire 10.77–81.

- ↑ Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, p. 134.

- ↑ Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City, p. 146; Hopkins, "The Political Economy of the Roman Empire," p. 191; Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, p. 134.

- ↑ Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ John E. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), pp. 144, 178; Kathryn Hinds, Everyday Life in the Roman Empire (Marshall Cavendish, 2010), p. 90.

- ↑ Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, p. 140ff.

- ↑ Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, p. 136ff.

- ↑ Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Mark Grant, Galen on Food and Diet (Routledge, 2000), pp. 7, 11 et passim.

- ↑ Grant, Galen on Food and Diet, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ John Donahue, The Roman Community at Table during the Principate (University of Michigan Press, 2004, 2007), p. 9.

- ↑ Gowers, The Loaded Table, p. 17.

- ↑ Veronika E. Grimm, "On Food and the Body," in A Companion to the Roman Empire, p. 354.

- ↑ Grimm, "On Food and the Body," p. 359.

- ↑ Joan P. Alcock, Food in the Ancient World (Greenwood Press, 2006), p. 184.

- ↑ Pullum parthicum: pullum aperies a navi et in quadrato ornas. Teres pipe, ligusticum, carei modicum; suffunde liquamen; vino temperas. Componis in cumana pullum et condituram super pullum facis. Laser et vivum in tepida dissolvis, et in pullum mittis simul, et coques. Pipere aspersum inferes. A modernized version of this recipe appears in Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger, The Classical Cookbook (J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996), p. 108.

- ↑ Seo, "Cooks and Cookbooks," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 298.

- ↑ Cathy K. Kaufman, "Remembrance of Meals Past: Cooking by Apicius' Book," in Food and the Memory: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooker p. 125ff.

- ↑ Kaufman, "Remembrance of Meals Past," p. 125.

- ↑ Kaufman, "Remembrance of Meals Past," p. 125ff.

- 1 2 Edwards, "Philology and Cuisine in De Re Coquinaria," p. 258.

- ↑ De Re Coquinaria 4.141.; Seo, "Cooks and Cookbooks," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 299.

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Vitellius 13.2; Gowers, The Loaded Table, p. 20.

- ↑ Livy 39.6; Seo, "Cooks and Cookbooks," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 298; Gowers, The Loaded Table,, p. 16.

- ↑ Peter Garnsey, "The Land," in Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire A.D. 70–192 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), vol. 11, p. 695.

- ↑ Mireille Corbier, "Coinage, Society, and Economy," in Cambridge Ancient History: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337 (Cambridge University Press, 2005), vol. 12, p. 404; Harris, "Trade," in CAH 11, p. 719.

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 14.55; Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 200.

- ↑ Harris, "Trade," in CAH 11, p. 720.

- ↑ Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Faas (2005), p. 29.

- ↑ Seo, "Cooks and Cookbooks," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 299.

- 1 2 Grimm, "On Food and the Body," p. 356.

- ↑ Matthew B. Roller, Dining Posture in Ancient Rome (Princeton University Press, 2006), p. 96ff.

- ↑ Quintilian, Institution Oratoria 1.2.7–8, scolds parents for behaving improperly at dinner parties when their children are in attendance; Roller, Dining Posture in Ancient Rome, p. 160.

- ↑ Katherine M.D. Dunbabin, "The Waiting Servant in Later Roman Art," in Roman Dining (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), p. 115ff.

- ↑ Paul Erdkamp, "War and State Formation," in A Companion to the Roman Army (Blackwell, 2011), p. 102.

- 1 2 Erdkamp, "War and State Formation," pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Seo, "Food and Drink, Roman," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 201.

- ↑ Tacitus, Germania 23; Gowers, The Loaded Table, p. 18.

- ↑ Musonius 18; Grimm, "On Food and the Body," p. 363.

- ↑ Massimo Montanari, "Romans, Barbarians, Christians: The Dawn of European Food Culture," in Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present (Columbia University Press, 1999, originally published in French 1996), p. 166.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 18.105; Gowers, The Loaded Table, p. 17.

- ↑ Grimm, "On Food and the Body," pp. 365–366.

- ↑ "Foodstuff," in Late Antiquity, p. 455; Montanari, "Romans, Barbarians, Christians," p. 165–167.

- ↑ Montanari, "Romans, Barbarians, Christians," p. 165–167.