| Maximinus Thrax | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

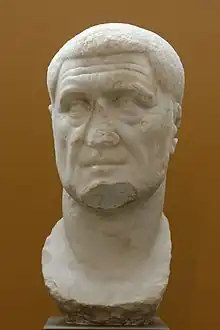

Bust, Capitoline Museums, Rome | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | c. March 235 – June 238[1] | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Severus Alexander | ||||||||

| Successors | Pupienus and Balbinus | ||||||||

| Rivals | Gordian I and II | ||||||||

| Born | c. 173 (?) Thracia | ||||||||

| Died | 238 (aged ~65) Aquileia, Italy | ||||||||

| Spouse | Caecilia Paulina | ||||||||

| Issue | Gaius Julius Verus Maximus | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Unknown, possibly Micca[3] | ||||||||

| Mother | Unknown, possibly Ababa[3] | ||||||||

Maximinus Thrax (Latin: Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus "Thrax"; c. 173 – 238) was a Roman emperor from 235 to 238. Born of Thracian origin – giving the nickname "Thrax" ("the Thracian"), he rose up through the military ranks, ultimately holding high command in the army of the Rhine under Emperor Severus Alexander. After Severus was murdered in 235, he was proclaimed emperor by the army, beginning the Crisis of the Third Century.

His father was an accountant in the governor's office and sprang from ancestors who were Carpi (a Dacian tribe), a people whom Diocletian would eventually drive from their ancient abode (in Dacia) and transfer to Pannonia.[4] Maximinus was the commander of the Legio IV Italica when Severus Alexander was assassinated by his own troops in 235. The Pannonian army then elected Maximinus emperor.[5]

In 238 (which came to be known as the Year of the Six Emperors), a senatorial revolt broke out, leading to the successive proclamation of Gordian I, Gordian II, Pupienus, Balbinus, and Gordian III as emperors in opposition to Maximinus. Maximinus advanced on Rome to put down the revolt, but was halted at Aquileia, where he was assassinated by disaffected elements of the Legio II Parthica.

Maximinus is described by several ancient sources, though none are contemporary except Herodian's Roman History. He was a so-called barracks emperor of the 3rd century;[6] his rule is often considered to mark the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century. Maximinus was the first emperor who hailed neither from the senatorial class nor from the equestrian class.

Background

The names "Gaius Julius" suggest that his family acquired Roman citizenship during the reign of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, as freedmen and newly integrated Romans always adopted the names of their former masters.[7] His exact birth date is unknown, but the Chronicon Paschale and the epitome of Joannes Zonaras, both written centuries later, record that he died at the age of 65, implying a birth in 173.[8][9]

Herodian writes that Maximinus was of Thraco-Roman origin.[10] According to the notoriously unreliable Historia Augusta, he was born in Thrace or Moesia to a Gothic father and an Alanic mother;[11] however, the supposed parentage is a highly unlikely anachronism, as the Goths are known to have moved to Thrace from a different place of origin much later in history and their residence in the Danubian area is not otherwise attested until after Maximinus' death. British historian Ronald Syme, writing that "the word 'Gothia' should have sufficed for condemnation" of the passage in the Historia Augusta, felt that the burden of evidence from Herodian, Syncellus and elsewhere pointed to Maximinus having been born in Moesia.[12]

The references to his "Gothic" ancestry might refer to a Thracian Getic origin (the two populations were often confused by later writers, most notably by Jordanes in his Getica), as suggested by the paragraphs describing how "he was singularly beloved by the Getae, moreover, as if he were one of themselves" and how he spoke "almost pure Thracian".[13] On the contrary, Bernard Bachrach suggests that the Historia Augusta use of a term not used in Maximinus time – "Gothia" – is hardly sufficient cause to dismiss its account. After all, the names it gives for Maximinius' parents are legitimate Alan and Gothic appellations. Hence, Bachrach argues, the most straightforward explanation is that the author of the Historia Augusta relied on a legitimate third century source, but substituted its terminology for that concurrent in his own day.[14] Accordingly, Maximinus' ancestry remains an open question.

His background was, in any case, that of a provincial of low birth, and he was seen by the Senate as a barbarian, not even a true Roman, despite Caracalla’s edict granting citizenship to all freeborn inhabitants of the Empire.[15] According to the Augustan History, he was a shepherd and bandit leader before joining the Imperial Roman army, causing historian Brent Shaw to comment that a man who would have been "in other circumstances a Godfather, [...] became emperor of Rome."[16] In many ways, Maximinus was similar to the later Thraco-Roman emperors of the 3rd–5th century (Licinius, Galerius, Aureolus, Leo I, etc.), elevating themselves, via a military career, from the condition of a common soldier in one of the Roman legions to the foremost positions of political power. He joined the army during the reign of Septimius Severus.[17]

Maximinus was in command of Legio IV Italica, composed of recruits from Pannonia,[18] who were angered by Alexander's payments to the Alemanni and his avoidance of war.[19] The troops, who included the Legio XXII Primigenia, elected Maximinus, killing Alexander and his mother at Moguntiacum (modern Mainz).[20] The Praetorian Guard acclaimed him emperor, and their choice was grudgingly confirmed by the Senate,[15] who were displeased to have a peasant as emperor. His son Maximus became caesar.[15]

Rule

Consolidation of power

| |

| O: laureate draped and cuirassed bust of Maximinus

MAXIMINVS PIVS AVG GERM |

R: Maximinus holding sceptre; standard on either side |

| Silver denarius struck in Rome from February to December 236 AD; ref.: RIC 4 | |

Maximinus began his rule by eliminating the close advisors of Alexander.[21] His suspicions may have been justified; two plots against Maximinus were foiled.[22] The first was during a campaign across the Rhine, when a group of officers, supported by influential senators, plotted to destroy a bridge across the river, in order to strand Maximinus in hostile territory.[23] They planned to elect senator Magnus emperor afterwards, but the conspiracy was discovered and the conspirators executed. The second plot involved Mesopotamian archers who were loyal to Alexander. They planned to elevate Quartinus, but their leader Macedo changed sides and murdered Quartinus instead, although this was not enough to save his own life.[24]

Defense of frontiers

The accession of Maximinus is commonly seen as the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century (also known as the "Military Anarchy" or the "Imperial Crisis"), the commonly applied name for the crumbling and near collapse of the Roman Empire between 235 and 284 caused by various simultaneous crises.

Maximinus' first campaign was against the Alemanni, whom he defeated despite heavy Roman casualties in a swamp in the Agri Decumates.[25] After the victory, Maximinus took the title Germanicus Maximus,[15] raised his son Maximus to the rank of caesar and princeps iuventutis, and deified his late wife Paulina.[21] Maximinus may have launched a second campaign deep into Germania, defeating a Germanic tribe beyond the Weser in the Battle at the Harzhorn.[26][27] Securing the German frontier, at least for a while, Maximinus then set up a winter encampment at Sirmium in Pannonia,[15] and from that supply base fought the Dacians and the Sarmatians during the winter of 235–236.[21]

Infrastructure work

In 2019 Israeli researchers translated a milestone found in the Moshav Ramot village in the Golan Heights. They were able to identify the name of Maximinus on the milestone. The roads themselves were much older, suggesting that a massive renovation project was undertaken during his rule on those roads.[28]

Gordian I and Gordian II

| Part of a series on Roman imperial dynasties |

| Year of the Six Emperors |

|---|

| AD 238 |

|

Early in 238, in the province of Africa, a treasury official's extortions through false judgments in corrupt courts against some local landowners ignited a full-scale revolt in the province. The landowners armed their clients and their agricultural workers and entered Thysdrus (modern El Djem), where they murdered the offending official and his bodyguards[29] and proclaimed the aged governor of the province, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus (Gordian I), and his son, Gordian II, as co-emperors.[30] The Senate in Rome switched allegiance, gave both Gordian and Gordian II the title of Augustus, and set about rousing the provinces in support of the pair.[31] Maximinus, wintering at Sirmium, immediately assembled his army and advanced on Rome, the Pannonian legions leading the way.[21]

Meanwhile, in Africa, the revolt had not gone as planned. The province of Africa was bordered on the west by the province of Numidia, whose governor, Capelianus, nursed a long-standing grudge against the Gordians and controlled the only legionary unit (III Augusta) in the area.[32] Gordian II was killed in the fighting and, on hearing this, Gordian I hanged himself with his belt.[33]

Pupienus, Balbinus, and Gordian III

When the African revolt collapsed, the Senate found itself in great jeopardy.[34] Having shown clear support for the Gordians, they could expect no clemency from Maximinus when he reached Rome. In this predicament, they remained determined to defy Maximinus and elected two of their number, Pupienus and Balbinus, as co-emperors.[21] When the Roman mob heard that the Senate had selected two men from the patrician class, men whom the ordinary people held in no great regard, they protested, showering the imperial cortège with sticks and stones.[35] A faction in Rome preferred Gordian's grandson (Gordian III), and there was severe street fighting. The co-emperors had no option but to compromise, and, sending for the grandson of the elder Gordian they appointed him caesar.[36]

Defeat and death

Maximinus marched on Rome,[37] but Aquileia closed its gates against him. His troops became disaffected during the unexpected siege of the city, at which time they suffered from starvation.[38] In May or June 238, soldiers of the II Parthica in his camp assassinated him, his son, and his chief ministers.[34] Their heads were cut off, placed on poles, and carried to Rome by cavalrymen.[21][lower-alpha 1]

Pupienus and Balbinus then became undisputed co-emperors. However, they mistrusted each other, and ultimately both were murdered by the Praetorian Guard, making Gordian III sole surviving emperor. Unable to reach Rome, Thrax never visited the capital city during his reign.[39]

Politics

Maximinus doubled the pay of soldiers;[17] this act, along with virtually continuous warfare, required higher taxes. Tax collectors began to resort to violent methods and illegal confiscations, further alienating the governing class from everyone else.[21]

According to early church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, the Imperial household of Maximinus' predecessor, Alexander, had contained many Christians. Eusebius states that, hating his predecessor's household, Maximinus ordered that the leaders of the churches should be put to death.[40][41] According to Eusebius, this persecution of 235 sent Hippolytus of Rome and Pope Pontian into exile, but other evidence suggests that the persecutions of 235 were local to the provinces where they occurred rather than happening under the direction of the Emperor.[42]

According to Historia Augusta, which modern scholars however treat with extreme caution:

The Romans could bear his barbarities no longer – the way in which he called up informers and incited accusers, invented false offences, killed innocent men, condemned all whoever came to trial, reduced the richest men to utter poverty and never sought money anywhere save in some other's ruin, put many generals and many men of consular rank to death for no offence, carried others about in waggons without food and drink, and kept others in confinement, in short neglected nothing which he thought might prove effectual for cruelty – and, unable to suffer these things longer, they rose against him in revolt.[43]

Appearance

Ancient sources, ranging from the unreliable Historia Augusta to accounts of Herodian, speak of Maximinus as a man of significantly greater size than his contemporaries.[46][47] He is, moreover, depicted in ancient imagery as a man with a prominent brow, nose, and jaw (symptoms of acromegaly).[48] His thumb was said to be so large that he wore his wife's bracelet as a ring for it.

According to Historia Augusta, "he was of such size, so Cordus reports, that men said he was eight-feet, one finger (c. 2.4 metres) in height".[49] It is very likely however that this is one of the many exaggerations in the Historia Augusta, and is immediately suspect due to its citation of "Cordus", one of several fictitious authorities the work cites.[50]

Although not going into the supposedly detailed portions of Historia Augusta, the historian Herodian, a contemporary of Maximinus, mentions him as a man of greater size, noting that: "He was in any case a man of such frightening appearance and colossal size that there is no obvious comparison to be drawn with any of the best-trained Greek athletes or warrior elite of the barbarians."[51]

Some historians interpret the stories on Maximinus's unusual height (as well as other information on his appearance, like excessive sweating and superhuman strength) as popular stereotyped attributes which do no more than intentionally turn him into a stylized embodiment of the barbarian bandit[52] or emphasize the admiration and aversion that the image of the soldier evoked in the civilian population.[53]

See also

- Aspasius of Ravenna (his secretary as emperor)

Notes

- ↑ His death is sometimes dated to 24 June. This is based on the "3 years 4 months 2 days" reign-length given by the (mostly inaccurate) Chronograph of 354. Papyri show that Pupienus and Balbinus were recognized in Thebes by 21 July 238, meaning that their proclamation probably took place the month before. Some historians interpreted the Chronograph's figure as "3 years 3 months and 2 days". This gives 24 June reckoning from 22 March 235, the date of Alaxander's death (although some time did pass between Maximinus' proclamation and Alexander's death).[1]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Rea, J. R. (1972). "O. Leid. 144 and the Chronology of A. D. 238". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 9: 1–19. JSTOR 20180380.

- ↑ Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- 1 2 Historia Augusta, Maximinus, 1:6

- ↑ Roman Antiquities, book XXVIII, Ammianus Marcellinus.

- ↑ Pat Southern (16 December 2003). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-134-55381-5.

- ↑ Kerrigan, Michael (2016). The Untold History of the Roman Emperors. Cavendish Square. p. 248. ISBN 9781502619112. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ↑ Salway, Benet (1994). "What's in a Name? A Survey of Roman Onomastic Practice from c. 700 B.C. to A.D. 700" (PDF). Journal of Roman Studies. 84: 124–145. doi:10.2307/300873. JSTOR 300873. S2CID 162435434.

- ↑ Chronicon Paschale (7th century), Olympiad 253–4. His reign is given to the wrong years, however.

- ↑ Zonaras (c. 1120) Epitome xvii.16. He also records a reign of six years, a copyist error.

- ↑ Herodian, 7:1:1–2

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Maximinus, 1:5

- ↑ Syme 1971, pp. 182, 185–186.

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Maximinus, 2:5

- ↑ Bachrach, Bernard S. A History of the Alans in the West: From Their First Appearance in the Sources of Classical Antiquity through the Early Middle Ages. 14: n.28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2003, p. 64.

- ↑ Shaw 1984, p. 36.

- 1 2 Potter 2004, p. 168.

- ↑ Herodian, 8:6:1

- ↑ Southern 2003, p. 63.

- ↑ Potter 2004, p. 167.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Meckler 2022.

- ↑ Potter 2004, p. 169.

- ↑ Herodian, 7:1:5–6

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Maximinus, 11

- ↑ Herodian, 7:2:7

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Two Maximini. 12:1–4

- ↑ Herodian, 7:2:3

- ↑ Amanda Borschel-Dan. "Cryptic Golan milestone found to be monument to low-born Roman emperor's reign". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ↑ Herodian, 7:4:6

- ↑ Southern 2003, p. 66.

- ↑ Zonaras, 12:16

- ↑ Potter 2004, p. 170.

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Maximinus, 19:2

- 1 2 Southern 2003, p. 67.

- ↑ Herodian, 7:10:5

- ↑ Drinkwater, John (2007). "Maximinus to Diocletian and the 'Crisis'". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. XII (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 32.

- ↑ Zosimus, 1:12

- ↑ Herodian, 8:5:4

- ↑ Hekster, Olivier (2008). Rome and its Empire, AD 193–284. Edinburgh University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780748629923. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ↑ Eusebius. "Church History". Book 6, Chapter 28. New Advent. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ Papandrea, James L. (23 January 2012). Reading the Early Church Fathers: From the Didache to Nicaea. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809147519.

- ↑ Graeme Clark, "Third-Century Christianity", in the Cambridge Ancient History 2nd ed., volume 12: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337, ed. Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Averil Cameron (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 623.

- ↑ "Historia Augusta • The Two Maximini". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Frederik Poulsen, Catalogue of Ancient Sculpture in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, 1951, no.744

- ↑ Poulsen, Frederik (1951). Catalogue of Ancient Sculpture in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. pp. 517-518 (no. 744, I.N. 818).

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Maximinus, 2:2

- ↑ Herodian, 7:1:2

- ↑ Klawans, Harold L. The Medicine of History from Paracelsus to Freud, Raven Press, 1982, New York, 3–15

- ↑ Historia Augusta, "Life of Maximinus", 6:8

- ↑ Syme 1971, pp. 1–16.

- ↑ Herodian, 7:1:12

- ↑ Thomas Grünewald, transl. by John Drinkwater. Bandits in the Roman Empire:, Myth and Reality, Routledge, 2004, p. 84. ISBN 0-415-32744-X

- ↑ Jean-Michel Carrié in Andrea Giardina (ed.), transl. by Lydia G. Cochrane. The Romans, University of Chicago Press, 1993, pp. 116–117. ISBN 0-226-29050-6

Sources

- Ancient sources

- Herodian (c. 230), Roman History, Book 7

- Historia Augusta (c. 240), Life of Maximinus

- Aurelius Victor (c. 400), Epitome de Caesaribus

- Zosimus (c. 500), Historia Nova

- Joannes Zonaras (c. 1120), Compendium of History extract: Alexander Severus to Diocletian: 222–284

- Modern sources

- Shaw, Brent D. (November 1984). "Bandits in the Roman Empire". Past & Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 105 (105): 3–52. doi:10.1093/past/105.1.3. JSTOR 650544.

- Southern, Pat (2003). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-134-55380-8.

- Syme, Ronald (1971). Emperors and biography: studies in the 'Historia Augusta'. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814357-4.

- Potter, David Stone (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: Ad 180–395. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10057-1.

- Meckler, Michael L. (2022), "Maximinus Thrax (235-238 A.D.)", De Imperatoribus Romanis

Further reading

- A. Bellezza: Massimino il Trace, Geneva 1964.

- Henning Börm: Die Herrschaft des Kaisers Maximinus Thrax und das Sechskaiserjahr 238. Der Beginn der Reichskrise?, in: Gymnasium 115, 2008.

- Jan Burian: Maximinus Thrax. Sein Bild bei Herodian und in der Historia Augusta, in: Philologus 132, 1988.

- Lukas de Blois: The onset of crisis in the first half of the third century A.D., in: K.-P. Johne et al. (eds.), Deleto paene imperio Romano, Stuttgart 2006.

- Karlheinz Dietz: Senatus contra principem. Untersuchungen zur senatorischen Opposition gegen Kaiser Maximinus Thrax, Munich 1980.

- Frank Kolb: Der Aufstand der Provinz Africa Proconsularis im Jahr 238 n. Chr.: die wirtschaftlichen und sozialen Hintergründe, in: Historia 26, 1977.

- Adolf Lippold: Kommentar zur Vita Maximini Dua der Historia Augusta, Bonn 1991.

- Loriot, Xavier (1975). Les premières années de la grand crise du IIIe siècle: De l'avènement de Maximin de Thrace (235) à la mort de Gordien III (244). Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. Vol. II.2. B.: De Gruyter. pp. 657–787.

External links

- Maximinus coinage

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.