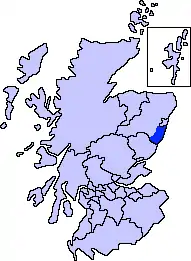

Fowlsheugh is a coastal nature reserve in Kincardineshire, northeast Scotland, known for its 70-metre-high (230 ft) cliff formations and habitat supporting prolific seabird nesting colonies. Designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) by Scottish Natural Heritage, the property is owned by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.[1] Fowlsheugh can be accessed by a public clifftop trail, or by boats which usually emanate from the nearby harbour at the town of Stonehaven. Tens of thousands of pelagic birds return to the site every spring to breed, after wintering at sea or in more southern climates, principal species being puffins, razorbills, kittiwakes, fulmars and guillemots.

Due to global warming, the planktonic species previously present that prefer cold water are not available in the quantity required to support the historically large sandeel population.[2] Added to the problem has been overfishing of the Scottish sandeel, further reducing the numbers of this dietary staple for puffins and other local seabirds.[3]

Geology and topography

The sheer cliffs of Fowlsheugh are actually undercut in some places by erosive force of the North Sea wave action and associated strong marine winds, giving rise to cliff overhangs in numerous stretches of the blufftop trail. (Off shore winds commonly attain mean velocities of 80 kilometres per hour here, especially in winter months.) The underlying rock formation is known as Old Red Sandstone, which occurs from Dunnottar Castle five kilometres north to the town of Catterline seven kilometres south. This sandstone formation may be as thick as 2700 metres.

In places the fissured red-and-green-coloured sandstone is replaced by picturesque conglomerate with roundish stones varying in diameter from two to thirty centimetres (historically known as puddingstone in this region of Kincardineshire).[4] In other places more greenish volcanic extrusions are evident as harder veins within the sandstone bluffs.

Where the rock faces meet the North Sea, there are several sea caves accessible only by small boat. The deepest cave known locally as the “Gallery” intrudes a full hundred metres westward beneath the fertile barley fields high above. In the northern extremity of the Fowlsheugh is an offshore skerry named Craiglethy, and slightly further a skerry called Gull Craig. These lower lying rocky outcrops are an integral part of the Fowlsheugh Preserve, hosting seabird nests as well as a few harbour seals on Craiglethy, who can be seen hauling out or sunbathing on summer afternoons. Craiglethy is composed only of sandstone and volcanic material, any original overlying conglomerate material having been long eroded. There are also some volcanic sea stacks along the shoreline, vestiges of the harder rock formations surviving the erosion of surrounding softer rocks by millennia of wave action and salt spray.

History

Historically there has been human recognition of Fowlsheugh as a unique bird area for at least five centuries, culminating in its present-day designations of Important Bird Area (IBA), Special Protection Area (SPA) and SSSI (as noted above).

This historic interest has also translated into reasonably good bird counts over at least the last century. As a glimpse into Fowlsheugh in early Victorian times, James Anderson wrote:

"a remarkable rock of the conglomerate or plum pudding species called Fowls Heugh, about a mile long and two hundred feet high, quite perpendicular and in some places overhanging, often visited by sportsmen on account of innumerable sea fowl, of the kittiwake species, which resort to it in the breeding season; finding convenient places for depositing their eggs in the recesses formed by the vacant beds of pebbles"[5]

It is documented that in the 19th century not only did hunters journey to Fowlsheugh to shoot seabirds, but rock climbers would rappel down the steep cliffs in search of the prized seabird eggs, much in the manner described of Saint Kilda. The rappelers would likely have anchored their pitons in the rock itself, as the loose soil above is not endowed with much fastening strength; however, these sandy loam soils are ideal for rabbit warrens that are time-shared by the puffins when the latter are in residence at Fowlsheugh.

About the year 1900 the Crown leased fishing rights at the base of Fowlsheugh to private interests, who proceeded to fish the North Sea close to the cliff faces using extensive systems of nets. The resulting entrainment of guillemots led to such great bird mortality, as well as to public outcry, that fishing lets were abandoned the following year. In 1920 fulmars arrived at Fowlsheugh to breed from St. Kilda.

Conservation status

International recognition of Fowlsheugh has been established primarily due to the large and productive seabird colonies present. On August 31, 1992 Special Protection Area (SPA) status was conferred with .EU code designation of UK9002271. The Fowlsheugh extent has been recorded as an area of only 10.15 hectares in size, making the seabird density one of the greatest in Europe.

Birdlife

In excess of 170,000 birds inhabit Fowlsheugh at the peak breeding season between April and late July. This value places Fowlsheugh as the second largest seabird colony in Britain and surpasses the criterion of 20,000 birds to qualify as a protected area of international seabird importance under European Union Directive 79/409. Bird species present are primarily auks and gulls, which feed in nearby offshore waters as well as more distant North Sea reaches. Most of the nests are constructed on precarious perches nestled in the virtually vertical cliffs of the basalt and conglomerate. During breeding season the bluffs are dense in birds arriving, departing and feeding in the waters below. Sound levels from birds have been measured as high as 69 dBA for a one-hour interval.

As of 2005 about 18,000 breeding pairs of kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) return to Fowlsheugh each year, making their nests on some of the most vertical parts of the landscape from muck, seaweed and local grasses. This population level significantly decreased from the 1992 kittiwake count of 34,870 breeding pairs of this seabird. The 1992 value represented 1.1 percent of all North Atlantic breeding pairs of kittiwakes. This population level caused the site to qualify under Article 4.2 of the European Union Directive 79/409 by supporting populations of European importance of this migratory species. From the cliff overhangs above, it is easy to view the parent feeding of these chicks by regurgitation.

Under the 1992 bird count there were 40,140 breeding pairs of guillemot (Uria aalge), representing at least 1.8 percent of this breeding East Atlantic seabird population. Smaller numbers of other seabirds nest at Fowlsheugh, including Atlantic puffin (Fratercula Arctica), razorbill (Alca torda), herring gull (Larus argentatus), and fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). Occasionally a peregrine falcon disturbs nesting kittiwakes as it swoops by the cliff edges. Lesser numbers of lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus), great black-backed gull (Larus marinus) and common shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) are also to be found.

Marine life

In the North Sea waters at the base of the cliffs can be found certain marine mammals, including the common seal (Phoca vitulina) and the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus). Seals can be observed in summer months hauling out on the rugged rock formation of Craiglethy Skerry. Further offshore are frequently sighted dolphins. Bony fishes found in the offshore waters include Atlantic shad (Aosa sapidissima), Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), and brown trout (Salmo trutta). Marine algae occurring immediately offshore at the Fowlsheugh Nature Reserve include Dudresnaya verticillata, Sauvageaugloia griffithsiana, and Streblonema infestans.

Terrestrial flora and fauna

On the clifftops are found a variety of flowering plants and grasses that offer additional biota infrastructure for the extensive butterfly populations resident at Fowlsheugh. Most of the blooming species flower in the period April through August. Representative flowering plants that occur at Fowlsheugh are: Achillea millefolium, Achillea ptarmica, Carex spicata, Carlina vulgaris, Festuca arundinacea, Salix viminalis, Sambucus nigra, Helianthemum nummularium (common rock-rose) and viola. Common rock-rose is the only host plant for the northern brown argus butterfly. Some of these species cling to the rough cliff verticals where patches of soil are found, while most of these species grow on the fertile blufftop soil tangent to the agricultural soils immediately west, which grow barley and other grains as well as afford pasture for sheep and cattle.

Numerous species of butterfly are found[6] at Fowlsheugh, including:

- Aglais urticae, small tortoiseshell

- Argynnis aglaja, dark green fritillary

- Aricia artaxerxes, northern brown argus, designated as a Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Species in the UK

- Coenonympha pamphilus, small heath

- Erebia aethiops, Scotch argus

- Hipparchia semele, grayling, designated as a Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Species in the UK (marked decline)

- Lycaena phlaeas, small copper

- Maniola jurtina, meadow brown

- Pieris brassicae, large white

Practical information

The Fowlsheugh Nature Reserve is most readily accessed on foot from the hamlet of Crawton, which is situated and signposted about one kilometre east of the A92 coast highway. There is a small carpark near the trailhead, with limited turnaround capability for larger vehicles. There is no limitation as to time of access of the trail as of 2006 and there is no admission cost for using the trail. By boat, out of Stonehaven Harbour, there are regular small craft trips available for a moderate charge during the months of May to July, which reach the cliff bases of Fowlsheugh and even traverse some of the marine waterway caves.

References

- ↑ "Fowlsheugh Nature Reserve, Aberdeenshire, Scotland".

- ↑ Rob Hume, Fowlsheugh, Royal Society for Protection of Birds, summer 2006, vol 21, no. 2

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, Aberdeenshire Coastline, Lumina Press, Aberdeen, March, 2006

- ↑ Archibald Watt, Highways and Byways Round Kincardineshire, Gourdas House Publishers, Aberdeen, (1985)

- ↑ James Anderson, The Black Book of Kincardineshire (1843)

- ↑ UK National Diversity Network (2006)