Francisco Alonso Liongson | |

|---|---|

A portrait of Francisco Alonso Liongson | |

| Born | Francisco Liongson y Alonso July 1, 1896 |

| Died | May 14, 1965 (aged 68) |

| Education | Licentiate in Civil Law, Bachelor of Arts |

| Known for | playwriting |

| Parent(s) | Francisco Tongio Liongson María Dolores Alonso |

| Relatives | Pedro Tongio Liongson (uncle) |

Francisco Alonso Liongson (July 1, 1896 – May 14, 1965) was a Filipino writer and playwright. He was born into an Ilustrado family from Pampanga, Philippines at the turn of the 20th century and raised with the revolutionary values of an emerging Philippine identity which held freedom, justice, honor, patriotism and piety sacred. He witnessed the rapid changes that transformed the Philippines from a repressed society cloistered in a Spanish convent for over 300 years into modern, hedonistic consumers of American Hollywood glamor for 50 years. This period of transition brought instabilities to core family values as the generation gaps wreaked havoc on the social, political, economic and political foundations of a young nation. It was a period of experimentation where the natives began to grapple a new democratic way of life and self-rule; where sacred paternalistic relationships were giving way to egalitarian modes; where traditional gender and familial roles were questioned, and where a new foreign language and the need for a national alternative were alienating the nation from understanding the aspirations of its elders. Liongson, in his unique, inimitable literary style captured snap shots of these struggles with anachronism in plays and articles written in the language that he mastered and loved best, Spanish. His works have since become precious gems of Philippine literature in Spanish and historic records of the Filipino psyche and social life between 1896 and 1950.

Early years

"Don Paco", as he was better known, was born in Bacolor, Pampanga, Philippines, a month before the Philippine Revolution was unleashed on August 23, 1896.[1] His father, Dr. Francisco Tongio Liongson, was a Spanish-trained medical doctor and a contemporary of José Rizal during his student days in Spain.[2] A great influence on his son, Dr. Liongson was actively involved in the struggle for independence and became Pampanga's governor and first Senator to the Philippine Legislature.[3] Don Paco's mother was Maria Dolores Alonso-Colmenares y Castro, a native of Badajoz, Spain whom his father met and married in Madrid.[4] His mother died soon after his birth. He was raised since by his spinster aunt, Isabel Tongio Liongson.

His early studies were in his hometown school of Don Modesto Joaquin. He next transferred to the Colegio de San Juan de Letran in Manila where he earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1911[5] He pursued his university studies in law at the University of Santo Tomas where he graduated with the Licentiate in Civil Law in 1916.[6] Having passed the bar examination given by the Philippine Supreme Court and was included into the rolls on November 6, 1916,[7] he traveled to neutral Spain to meet his late mother's family for the first time. His trip to the United States was delayed by the latter's entry into the First World War. His extended three-year sojourn in Spain provided the opportunity to absorb the language, culture and literary arts of the Iberian peninsula. The literary works of Spaniard Miguel de Cervantes, particularly the early 17th century novel Don Quixote, would soon prove to be a propitious influence in the young man's future.

He traveled to the United States before returning to the Philippines in 1919[8] not knowing of his father's untimely death. Upon his arrival in Manila, the shocking, unexpected news of his father's demise caused the first epileptic seizure that will continue to debilitate him for the rest of his life. Restrained from pursuing an active professional practice, he engaged in a more leisurely lifestyle administering a sugar fortune that he inherited at a young age. He married his first cousin, Doña Julita Eulalia Ocampo, who would become his indispensable partner in life and particularly in his contributions to Philippine literature in Spanish.

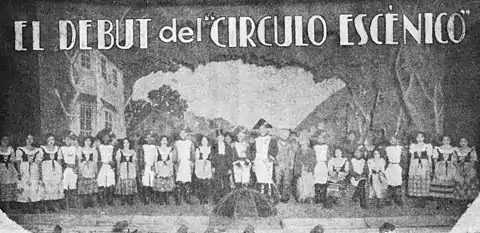

Circulo Escenico

Don Paco was one of the founders and first president of the Circulo Escenico, a Spanish dramatic club of aficionados founded in Bacolor, Pampanga that rose to national prominence and became the longest surviving organization of its kind in the Philippines.

The club traces its origins to a fund-raising event to build a school organized by the town's parish priest, Fr. Pedro P. Santos. The activity involved a dramatic presentation of an all-male cast, one act literary-musical zarzuela entitled, Morirse a Tiempo, by members of the community. The event was such a great success that the enthusiasm and interest generated within the town and throughout the province demanded another presentation of a grander scale. Indiana, the next presentation of the community involving characters of both genders, was packed to the rafters prompting the group of performers to form an association of aficionados of the theatrical arts soon after. The goals of the proposed club were 'to promote and maintain the conservation of the Spanish language and to develop talents and aptitude for the stage; allocating time for recreation and solace for the spirit as well as art and enthusiasm among a public tired of cinema's vulgarity.' The by-laws were approved with the first board of directors elected in August, 1922.[9]

Circulo Escenico was officially inaugurated on January 6, 1923 in Teatro Sabina Bacolor, Pampanga with a grand gala presentation of a comedy in two acts, Jarabe de Pico and a one act zarzuela, Doloretes, launching its artistic and charitable endeavor, and its pro-Hispanic cultural mission. Basking in the subsequent successes and positive commentaries from the Manila press, the club ventured to premiere Nobel Prize in Literature Winner Jacinto Benavente's comedy in two acts Los Intereses Creados and a one-act zarzuela, La Cancion de Olvido , in the capital in June, 1929. The performances were received with much acclaim and admiration by the appreciative Manila public that the Circulo decided to make the capital its new home.[10] Except for the period of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, the club sustained annual performances for thirty-one years until 1955 when it quietly exited the stage. In 1977, Dr. Mariano M. Alimurung resurrected the Circulo featuring mainly Don Paco's original works until 1980 when he met an untimely death.

The Circulo was headed by able presidents through the years. They included Francisco A. Liongson (1923, 1950) Ignacio P. Santos (1924–28, 1933), Jose Panlilio (1929–31), Antonio Abad (1932), Jose A. del Prado (1934), Primo Arambulo (1935), Francisco Zamora (1936, 1951), Ramon C. Ordoveza (1937, 1947), German Quiles (1938), Adolfo Feliciano (1939), Antonio G. Llamas (1940–44), Manuel Sabater (1945–46), Guillermo Dy Buncio (1948–49, 1952), Francisco Zamora (1951), Eduardo Viaplana (1953–55),[11] and Mariano M. Alimurung (1977–80).[12][13] In 1951, Don Paco was elected Honorary President for life.[14]

Literary works

Don Paco was regarded as the most prolific producer of Spanish theatrical works in the Philippines. They included: El Unico Cliente, Mi Mujer es Candidata, ¿Es Usted Anti o Pro?, 4-3-4-3-4, Viva La Pepa, El Pasado Que Vuelve, Juan de la Cruz, Las Joyas de Simoun, ¿Colaborador?, and Parity. Unfinished works included La Farsa de Hoy Dia, and Envejecer.[15]

El Unico Cliente is a comedy in one act, first staged on August 12, 1932. It dwells on how the household is neglected when the wife insists in practising a career.

Mi Mujer es Candidata is a comedy in one act, first staged on December 30, 1932. It was written when women first ran as candidates for public office in a general election. It discouraged women from getting involved in politics especially if they were married.

¿Es Usted Anti o Pro? is a comedy in one act, first staged on October 26, 1933. The title was inspired by the debates that led to the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act. The people was then divided into two factions: those in favor were called Pros, and those who were against were called Antis.

4-3-4-3-4 is a comedy in one act, first staged on February 12, 1935. It depicts the joy of two sweethearts for having won the sweepstakes first prize with ticket number 43434. The Philippine Charity Sweepstakes became a national indulgence in the quest for instant wealth. The Tagalog translation of the same title was written by Epifanio Matute.[16]

Viva La Pepa is a comedy in three acts, first staged on October 12, 1935. It was based on the campaign supporting economic protectionism for which an association called Proteccionismo Economico, Practico y Activo was organized and simply called PEPA. The play is a parody of the National Economic Protectionism Association (NEPA) which was founded in 1934 to hasten industrial development in preparation for independence contained in the Tydings–McDuffie Act.

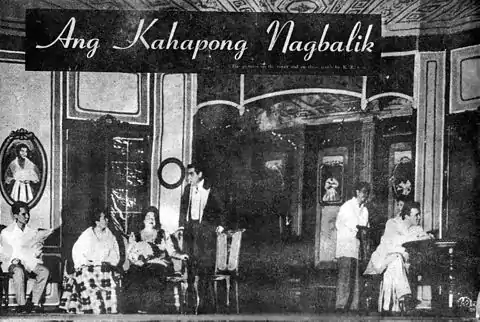

El Pasado Que Vuelve is a drama in one prologue, three acts and one epilogue, first staged on June 19, 1937. The play portrays the last years of the Spanish regime during the Philippine Revolution. It highlighted the good customs and virtues the country possessed in politics, society, morality, religion and love then, compared to the degeneration and corruption of contemporary values. Considered as Don Paquito's best work, the masterpiece was inspired by José Rizal's Noli Me Tángere and El filibusterismo. This play was the most repeatedly staged and had been translated into Tagalog and English. The Tagalog translation, Ang Kahapong Nagbalik, was written by Senator Francisco (Soc) Rodrigo during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.[17] The English translation, Shadows of the Past, was written and directed by Enrique J. Valdes in 1957.[18]

Juan de la Cruz is a drama in three acts, first staged on March 12, 1938 to celebrate the anniversary of the Philippine Commonwealth. The play deals with the tragedies that befall men when greed, power and lust disrupts the harmony in the home and the community at large. It features social unrest in the home and the barrio instigated by power brokers for political advantage and selfish interests. In Philippine imagery, Juan dela Cruz symbolizes the good, noble and honest Juan who has to carry the cross of adversity and suffering in life as a human being.

Las Joyas de Simoun is a drama in three acts, first staged on June 19, 1940. Act 2710 of 1917 allowed divorce in the Philippines for the first time in its history. Since then, a popular clamor to repeal it persisted. In touch with the sentiments of the times, the play portrayed a wise and fearless attack against divorce. The title is an allusion to José Rizal's character in El filibusterismo, Simoun, who uses his jewels and wealth to corrupt and destabilize society. The Tagalog translation, Ang Mga Hiyas ni Simoun, was written by Primo Arambulo in 1940.[19]

¿Colaborador? is a tragic-comedy farce in one prologue and three acts, first staged on March 7, 1948 on the Silver Anniversary celebration of Circulo Escenico. It was inspired by the pains and worries of every Filipino of being accused a Japanese collaborator during the Second Philippine Republic.

Parity is a comedy in one act, first staged on March 6, 1949. The play did not concern the 1947 Parity Rights plebiscite in the Philippines, a major controversy in everyone's mind at the time. It involved the parity and equality of rights between men and women which was an equally burning issue.

Don Paco was honored with the distinction of membership in the La Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española (Philippine Academy of the Spanish Language) on November 7, 1947 in recognition for his literary works.[20] He served as one of the judges in the Premio Zobel since then.[21]

Hispanic Twilight

The most prolific period of Spanish literature was during the American period in the History of the Philippines (1898–1946). Don Paco was among the well-known playwrights of the period, which included Claro M. Recto, Antonio Abad, Jesús Balmori, Pascual H. Poblete, Nicasio Osmeña and Benigno del Rio.[22] However, the legitimate stage couldn’t compete with movies for patronage and English was becoming a more dominant language. The introduction of English in the public school system in 1900 marked the death knell of Spanish in the Philippines.[23] Within thirty years, the ominous signs were beginning to show.

Circulo Escenico faced increasing difficulty in sourcing young actors and actresses. The regular performers were getting older and newer elements were not easy to come by. By the time the Third Philippine Republic was inaugurated in 1946, the patronage of the Spanish theater dramatically dwindled except for a few familiar old faces, who faithfully watched the Circulo's productions every year.[24] Measures were introduced to stem the tide of the Spanish demise as early as 1947 when Republic Act 343 or the Sotto Law was enacted. Unfortunately, the law made the teaching of Spanish only optional.[25] Circulo Escenico was in the forefront in the campaigns to make Spanish obligatory. The First Congreso de Hispanistas de Filipinas was held in 1950 to rally support for the language. Representing Circulo Escenico, Don Paco delivered his impassioned speech tracing Spain's legacy in the Philippines and underscoring the role of the Congress to awaken the country from its lethargy and to reaffirm its historic heritage and place in the Hispanic community of nations.[26] By May 1952, the Magalona Law or Republic Act 709 made Spanish compulsory in all universities and private schools for two consecutive years.[27]

In March 1953, the Spanish Minister for Foreign Relations Martin Artajo and his entourage arrived in the Philippines to grace the Second Congreso de Hispanistas.[28] In honor of the visiting dignitaries, the Executive Committee of the Congress scheduled a theatrical performance authored by a Filipino. At the recommendation of Academician Benigno del Rio, Circulo Escenico was commissioned to present El Pasado Que Vuelve for the occasion. Minister Artajo and his entourage failed to attend the performance. Not even the director of the local Instituto de Cultura Hispanica showed up. To onlookers, the apparent snub focused on the absurdity of Filipinos hankering for Spanish culture when even Spanish officials cared so little about it. Del Rio lamented the fact that the Spanish dignitaries missed what could have been the last presentation of a Spanish theatrical play in the land.[29] He proved prophetic when the growing disinterest for Spanish continued unabated, and Circulo Escenico quietly left the stage two years later.

In the last days of the Circulo, Don Paco was relentless in the struggle to keep Spanish alive. In what could have been his valedictory, he said ...

Those immortal words of the great Benavente in his play, 'Intereses Creados', aptly applies to the members of this Circulo: ‘That it is not all farce in the farce; because there is something divine in our lives that is real and eternal, and it does not end when the farce is over.’

Circulo Escenico may you age, neither by your years nor by your labor because they make you old and staunch your energies, but by the lack of Hispanic elements that time is claiming at its passage, whose breath and spirit are your life. Continue with your sublime and beautiful mission and always raise the curtains when you can, even if in the final act only two hands are left to applaud you and one heart that beats with yours, and like you, weeps at the somber sunset of a culture and the lingering agony of certain death of a rich and sonorous language which you continue to use with fervor under these skies whether on or off stage. Continue pushing the old and broken Thespian cart with your arms, even in its passing you see only fields of solitude and withering wastelands of a worn and near dead Hispanism. You belong to the Quixotic race, and like Quixote you will die fighting til the end.

Lady or Gentleman Circulista, may you continue riding the exhausted Rocinante of your ideals through the Philippine fields of Montiel; continue on your quest even if you need to fight like a Hidalgo, not with windmills, but with mills of steel that will leave you bloodied if not dead; because with your courage, tenacity and death, you would have demonstrated: that not by bread alone does man live; but by ideals; even if those ideals are found hidden behind the farcical cart, which sometimes laughs and sometimes cries for the solace and amusement of your public.[30]

Tributes

The Hispano-Filipino theater lives and Liongson is one of its most solid pillars. Liongson is part of a planetary system in which stars shine brilliantly in no despicable magnitude. Some have already departed; others live if at all in slumber. But of those who live, the genuine militant goldsmith and forger who is pounding constantly on the anvil in proper timing is without doubt, Francisco Liongson. The theatrical production of Liongson, which covers the most varied themes as much as its quality and its dimensions, inspires respect and faith in the most non-believer with regard to the depth of the Spanish theater in the Philippines.[31]

- Manuel C. Briones

Liongson, whose interests in theater began during his stay in Spain, is an edifying and active example to others because of his long and meritorious work for the theater. There are few who are his equal.[32]

The soul and the life of the meritorious artistic labor that is being realized by the Circulo Escenico is Sr. Liongson, who not satisfied with indefatigably involving himself with the exhausting work of preparing and directing the plays that the society performs on stage, also comes enriching the bitterness of the letters and of the Hispano-Filipino theater with the comedies he authored. And for the future survival of the Spanish language, Sr. Liongson has come to swell the ranks, each time more evident, of those who here cultivate it.[33]

- Segundo Telar

Don Paco Liongson can claim with well deserved pride that he has not limited himself to directing works entrusted to him but with the ability of a craftsman he was able to transform neophyte actresses and actors who are wanting in the Spanish language into creditable performers.[34]

- Andres Segur

FRANCISCO LIONGSON

In dreams of glory, in fields of hope

wondrous castles on stage he brings.

N’er his flesh torn or his lance broke

by the windmill's revolving wings.

His sword fails not thrusting words fair.

His spirit denies peregrines bar.

Like El Cid using his art's flair,

Spain he spreads through Philippines far.

I say in Liongson's honor my most sincere eulogy.

Let my words be filled with color,

and be filled with light, and be filled with music.

For he is a gentleman whom I admire and love

with the fervor that inspires great writers

and the love that great compatriots deserve. [35]

- Jesus Balmori

References

- ↑ Villa de Bacolor Cultural, Literary and Civic Foundation, Inc. Program Notes. Presentation of Posthumous Plaques of Merit to the outstanding sons of Bacolor and Crissot's immortal zarzuela, Alang Dios. Theater for the Performing Arts, Cultural Center of the Philippines. Manila, Philippines. 31 May 1975.

- ↑ Guerrero, Fernando Ma., Villanueva, Rafael. Directorio Oficial del Senado y de la Camara de Representantes, Cuarta Legislatura, Filipina Primer Periodo de Sesiones. Bureau of Printing. Manila 1917

- ↑ Guerrero et al.

- ↑ Fernandez Garcia, Matias. Parroquias Madrileñas de San Martín y San Pedro el Real: Algunos Personajes de su Archivo. Caparos Editores. p.252

- ↑ Letran Alumni Association, Inc. Colegio de San Juan de Letran Alumni Directory Vol. I. Manila. 1993, p. 96

- ↑ Old Legs Club. An Affair in Bacolor April 14, 1963. Bacolor, Philippines. 1963.

- ↑ Philippine Lawyer's Named Francisco Liongson - PhilippineLaw.info, retrieved on 10 October 2011

- ↑ Francisco Liongson Alonso Search Results-FamilySearch.org, retrieved on 10 October 2011

- ↑ Liongson, Francisco A. Historia Compendiada del Circulo Escenico Program Notes, Circulo Escenico presenta ¿Colaborador? San Beda College Auditorium. Manila. March 7, 1948. pp. 6-9.

- ↑ Liongson.

- ↑ Circulo Escenico. Programa. Que Solo Me Dejas! Conservatorio de Musica, Universidad de Santo Tomas. Manila. August 15–16, 1953

- ↑ Circulo Escenico. Programa. Noche de Gala en el Teatro del Circulo Escenico: 4-3-4-3-4 y Parity Philamlife Auditorium. Manila. September 28, 1977

- ↑ United Way-Albay and Circulo Escenico. Program. Two Plays: The Only One Client and Parity Bicol College Gym. Legaspi City. October 4, 1980

- ↑ Circulo Escenico. Programa. Gran Funcion de Gala en Conmemoracion del Dia de Hispanidad. Conservatorio de Musica, Universidad de Santo Tomas. Manila. October 21, 1951

- ↑ Santos, Ignacio P. Liongson and Contemporary Theaters. Symposium Series of 1965. Department of European Languages, University of the Philippines. Quezon City. 1965

- ↑ Dramatic Philippines. Nag-iisa sa Karimlan ni Claro M Recto (Dulang May Isang Yugto) kasama ang 4 3 4 3 4 ni Francisco Liongson (Dulang May Isang Yugto). Far Eastern University Auditorium. Manila: August 28–29, 1954.

- ↑ Esteves, A. Francisco Liongson. Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Vol. VII. Manila: CCP 1994, pp. 338-339.

- ↑ The Molave Players. The Molave Players Present Shadows of the Past, English version of F. Liongson's 'El Pasado Que Vuelve. Program. Girls Scout of the Philippines Auditorium. Manila: March 2, 1957

- ↑ Arambulo, Primo. Ang Mga Hiyas ni Simoun. Manila: 1940.

- ↑ Castrillo Brillantes, Lourdes. 81 Years of Premio Zobel: A Legacy of Philippine Literature in Spanish. Georgina Padilla y Zobel. Filipinas Heritage Library. Makati, Philippines. 2006, p. 31

- ↑ Castrillo Brillantes. p. 146, 159.

- ↑ Manuud, Antonio. Brown Heritage: Essays on Philippine Cultural Tradition and Literature. Quezon City : Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1967. p. 512

- ↑ Abad, Antonio. "Circulo Escenico, Baluarte del Español en Filipinas". Voz de Manila. 28 Junio 1950. pp. 2-5

- ↑ Abad.

- ↑ Rodao, Florentino. Spanish Language in the Philippines: 1900-1940. p. 105 www.florentinorodao.com/scholarly/sch97a.pdf Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

- ↑ Congreso de Hispanistas de Filipinas.Diario de sessiones del primer Congreso de Hispanistas de Filipinas. - Manila : Cacho Hermanos, 1950

- ↑ Rodao.

- ↑ Del Rio, Benigno. Alfilarazos. Voz de Manila. 11 March 1953. p.7

- ↑ Del Rio.

- ↑ Liongson, Francisco. Continua tu camino. Voz de Manila 31 March 1955 p. 4

- ↑ Briones, Manuel C. CIRCULO ESCENICO - Labor Magnifica y Meritoria por la Supervivencia del Idioma Castellano. Nueva Era 16 February 1948. p. 3, 8

- ↑ Veyra, Jaime C. de. La Hispanidad en Filipinas. 1953 p. 85

- ↑ Telar, Segundo. Las Joyas de Simoun. Excelsior Revista Mensual Ilustrada. Junio 1940.

- ↑ Segur, Andres. El Director Liongson y sus Pausas. Program Notes. Circulo Escenico presenta El Pasado Que Vuelve. Ateneo Auditorium. Manila. June 19, 1937. pp. 18-19

- ↑ Balmori, Jesus. Francisco Liongson. Spanish poem written in honor of Francisco Alonso Liongson. English translation by Francisco Liongson IV

External links

- Pride of Bacolor. Official Website of Bacolor, Pampanga, Philippines., retrieved on 10 October 2011.

- Farolan, Edmundo. El Teatro Hispano Filipino. Revista Filipina, retrieved on: 10 October 2011.

- Farolan, Edmundo. Literatura HispanoFilipina: Pasado, Presente Y Futuro. Revista Filipina, retrieved on: 10 October 2011.

- Direcciones hispanofilipinas/ Filipino-Spanish links: Philippine Spanish, Geocities.com, retrieved on: 10 October 2011

- Gómez Rivera, Guillermo. Spanish in the Philippines (Language: Spanish), El idioma español en las Filipinas, Las Islas Cuentan Hoy Con Medio Millon de Hispanohablantes, La Academia Filipina, ElCastellano.org, retrieved on: 10 October 2011

- Farolan, Edmundo (Director). Philippine Spanish, Philippine Poetry, La revista, Tomo 1 Número 7, Julio 1997 and AOL.com, retrieved on: 10 October 2011

- Fernández, Tony P. Philippine Spanish, La Literatura Española en Filipinas, La Guirnalda Polar - Neoclassic E-Press and VCN.BC.ca, May 4, 1997, retrieved on: 10 October 2011

- Real Academia Española, Diccionario de la lengua espanola (Spanish Dictionary), vigesima segunda edicion, RAE.es retrieved on: 10 October 2011

- Spanish in the Philippines, The Situation of Spanish in the Philippines Today and Other Hispano-Filipino Articles, FilipinoKastila.Tripod.com, retrieved on: 10 October 2011

- Pagina Web de Florentino Rodao sober España y Asia-Pacifico, retrieved on: 7 January 2012