Frederic W. Tilton | |

|---|---|

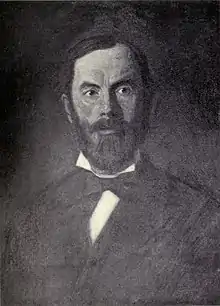

Portrait of Tilton presented to Phillips Academy in 1878 by Charles Moore. Painted from life by Stone.[1] | |

| 7th Principal of Phillips Academy | |

| In office 1871–1873 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Harvey Taylor |

| Succeeded by | Cecil Bancroft |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frederic W. Tilton May 14, 1839 Cambridge, Massachusetts, US |

| Died | December 16, 1918 (aged 79) Cambridge, Massachusetts, US |

| Resting place | Mount Auburn Cemetery |

| Spouse |

Ellen Trowbridge

(m. 1864–1910) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Harvard College (1862) University of Göttingen (1864)[2] |

Frederic William Tilton (May 14, 1839 – December 16, 1918) was an American educator and briefly the 7th Principal[lower-alpha 1] of Phillips Academy Andover from 1871 to 1873. At Andover, he was a transitional figure along with his successor Cecil Bancroft, adapting the school to a more modern curriculum.[4]

Early life

Tilton was born May 14, 1839, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Benjamin Tilton[lower-alpha 2] and Lucinda Newell as the youngest of three children. His elder siblings were Henry Newell and Benjamin Radcliffe Tilton.[2] He attended Cambridge public schools and graduated from the English Department of Cambridge High School in 1854. He spent the next two years with his elder siblings in their counting room in Boston but returned to high school for another two years to prepare for college.[5] He graduated from Harvard College with an A.B. in 1862.[6] He subsequently studied in Germany at the University of Göttingen for several months after traveling across Europe in England, Scotland, and Ireland.[5] He returned to Harvard and earned his A.M. in 1871.[7] His training prepared him for teaching, the career he would pursue for the next 27 years. In 1864 he married Ellen Trowbridge in Cambridge.[8]

Career

Soon after returning from Germany, Tilton became an instructor in Latin and Mathematics at the Highland Military Academy in Worcester, Massachusetts.[5] In 1867, he moved to Newport, Rhode Island, to take on the role of Superintendent of Public Schools.[8]

In 1871 Tilton, given his experience in teaching, received an eager offer from the Trustees of Phillips Academy for Principalship. He initially refused but eventually came to an agreement: $2,500 salary, an apartment in Double Brick House for him and his family, and the "approval of his views in regard to the administration of the Academy".[9][8] He was in a lot of ways different from his predecessor Samuel Harvey Taylor. Tilton believed that students ought to choose where they want to continue their studies. Historically, most graduates attended Yale College, and could do so simply with a letter of recommendation from Taylor. Students who wanted to attend Harvard were unprepared and needed outside tutoring. He changed the school's curriculum so that it met the requirements of any college, including Harvard. He revamped subjects such as mathematics, classics, and modern language. At an extra cost, students could take courses in languages such as German and French with Professor Oscar Faulhaber. On Sundays, students were required to attend two church services held by the Andover Theological Seminary. Intended for older students of the seminary, Tilton's pupils found them uninteresting and difficult to understand. He adjusted the Sunday schedule so Phillips Academy students no longer had to attend a second church service. Instead, they had a vesper service where notable figures would give short speeches. They were not necessarily religious and proved to be popular among all. At the end of Tilton's first year, seventeen students matriculated at Harvard, and everyone else to "the college of their choice".[4][10]

In addition to academics, Tilton brought about reform to how Phillips Academy dealt with disciplinary issues. Prior to Tilton, faculty had little sway in the curriculum and in the management of the student body. It was formerly solely the responsibility of the Principal. Under his administration, he held weekly faculty meetings to discuss individual students and make curriculum and disciplinary decisions as a group. He also created the position of Secretary of the Faculty. These changes improved faculty morale and drew qualified instructors to the school, including Edward G. Coy, who would remain in Andover until 1892.[4] Despite improvements, Tilton's responsibilities overwhelmed him. While Taylor was known to be strict, Tilton was not. An alumnus wrote of Tilton, he "did not have the force of character to succeed in disciplining the school along the line that Doctor Taylor followed."[11] He gives an anecdote:

"I remember Mr. Tilton one day stating in the school that a certain number of boys would be expelled if another bonfire were started in the yard. I happened to be among those he named. Well a bonfire was started and yet we were not expelled. Such statements, of course, hurt his power over the boys. Doctor Taylor would not, probably, have made such a statement but if he had he would have carried it out and every boy knew that he would."[11]

It was likely for this reason Tilton resigned from the principalship at Andover, March 17, 1873. In a statement to the Trustees, he cites his resignation "on the account of his health being insufficient to a longer continuance of so onerous a trust."[12] According to two histories of the school, Tilton moved "in the right direction" and "bridged...the gulf" between an antiquated and modern secondary school.[12][13]

In June 1873 Tilton left Andover and returned to Newport, where he would become the headmaster of the newly constructed Rogers High School, part of the public school system he was superintendent of two years prior. Rogers High School was named after the late William Sanford Rogers. He accepted the position on December 19, 1872, suggesting he was for some time dissatisfied with his previous office. He could also have been enticed by a raise, $3,500 a year in Newport as opposed to $2,500 in Andover.[14] The new building was dedicated January 21, 1874.[15] He would remain in Newport, with the exception of 1885 to 1886 with his family on a leave of absence in Europe, until 1890 when he retired to Cambridge, the city of his birth.[13][5]

Personal life

Tilton married Ellen Trowbridge, daughter of Harvard professor of German and writer John Howe Trowbridge and Adaline Richardson, on July 21, 1864.[5][2] They had four children together:

- William Frederic (born February 24, 1867) was born in Cambridge and attended Rogers High School in Newport before Harvard, where he attended from 1887 to 1890 but did not graduate. He earned his Doctorate of Philosophy at a university in Freiburg, Germany, in 1894. On January 10, 1910, he married Elizabeth Hewes. He spent his career in Cambridge as a social worker, supporting groups such as the "anti-alcohol movement".[16]

- Benjamin Trowbridge (born July 17, 1868) was a surgeon and professor. Born in Newport, Rhode Island, he followed a very similar educational path as his elder brother William. He attended Rogers High School, graduated from Harvard with an A.B. in 1890, and earned his M.D. in Freiburg in 1893. Afterward, he moved to New York City, where he would practice surgery and teach at Fordham University as a Professor of Clinical Surgery. He was recruited by the Medical Corps of the United States Army on December 20, 1917, for World War I and was sent to various hospitals in France, including Dr. Blake's Hospital in Paris (see image). He was discharged on February 15, 1919, and returned to his work in New York. He married Anna Billings Griggs of Tacoma, Washington, on September 14, 1905, and had two children: Susan Dimock (b. 1907) and Maud Trowbridge (b. 1909).[17]

- Ellen Maud (born February 29, 1872) married Frederic William Atherton of Boston on April 8, 1911.[18][19]

- Newell Whiting (born October 26, 1878) was a textile manufacturer. He was born in Newport and graduated from Harvard College in 1900. He lived primarily in New York and co-led the firm Harding, Tilton, & Company, which had locations in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. He married Mildred Bigelow of New York and had two daughters, Ellen and Daphne.[18] They divorced in 1918. His second wife was Elizabeth Alexandra Morton Breese; they married in 1921, and later divorced.[20]

Ellen Trowbridge died on January 5, 1910.[5]

Later life and other affiliations

Tilton returned to Cambridge in 1890 after retiring from his post as headmaster in Newport, only to travel in Europe again with his family for the next four years, where his two sons William Frederic and Benjamin Trowbridge would be educated. In 1894, he settled once again in Cambridge. During his career and retirement, he held a number of board positions. In Newport, he was a trustee and president of the Newport Hospital, a trustee of the Redwood Library, a member of the Rhode Island State Board of Education, director of the People's Library, and a member of the Newport Reading Room. In Cambridge, he was vice president, trustee, and member of the Investment Committee of the Cambridgeport Savings Bank, director of the Harvard Trust Company, a member of the Harvard Union and Oakley Clubs, a member of the Cambridge Club, and a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society.[6][5]

He visited Newport to deliver an address at the dedication of a second high school building to replace the first on January 31, 1906.[15] In 1910, he was listed as living at 86 Sparks Street, Cambridge.[7] Tilton died a widower on December 16, 1918.

Notes

- ↑ The contemporary name for the position is Head of School.[3]

- ↑ Benjamin Tilton (August 25, 1805 – November 23, 1882) was a banker and investor. He was born in Edgecomb, Maine, then part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and moved to Boston via boat in 1821. In Boston he became a clerk at a dry goods store. After marrying Lucinda Newell, daughter of Ebenezer Newell and Anna Whiting and granddaughter of Colonel Daniel Whiting, an officer in the French and Indian War and American Revolutionary War, in 1828, they lived in Boston and Brookline before settling in Cambridge in 1837. His banking career began later in his life. He founded the Harvard Bank in 1860 and was its president from March 1864 to his death. He was also president of the Cambridgeport Savings Bank from 1854 to 1882. He had other business interests in Boston and was apparently very successful. He died on November 23, 1882.[2]

References

- ↑ Fuess 1917, p. 330.

- 1 2 3 4 Eliot 1913, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ Trustees of Phillips Academy.

- 1 2 3 Allis 1979, p. 223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Harvard Class of 1862 1912, pp. 74–76.

- 1 2 Leonard 1908, p. 2057.

- 1 2 Harvard Alumni Association 1910, p. 675.

- 1 2 3 Fuess 1917, p. 324.

- ↑ Allis 1979, p. 221.

- ↑ Fuess 1917, pp. 325–327.

- 1 2 Allis 1979, p. 224.

- 1 2 Allis 1979, p. 225.

- 1 2 Fuess 1917, p. 329.

- ↑ Rhode Island Board of Education 1874, p. 147.

- 1 2 School Committee of the City of Newport, Rhode Island 1901, p. 31.

- ↑ Faulkner, Cabot & Darling 1921, p. 154.

- ↑ Faulkner, Cabot & Darling 1921, p. 153.

- 1 2 Harvard Class of 1862 1912, p. 74-76.

- ↑ Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association 1911, p. 728.

- ↑ "NEWELL W. TILTON, 84, INVESTMENT BANKER". The New York Times. 1963-06-28. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

Bibliography

- Allis, Frederick Scouller Jr. (1979). Youth From Every Quarter: A Bicentennial History of Phillips Academy, Andover. Andover: Phillips Academy. ISBN 978-0-87451-157-4. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- Eliot, Samuel Atkins (1913). A History of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Cambridge, MA: The Cambridge Tribune. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Faulkner, Robert E.; Cabot, Frederick P.; Darling, Eugene A. (1921). Seventh Report of the Class of 1890 of Harvard College 1920: Thirtieth Anniversary. Concord, NH: The Rumford Press. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Fuess, Claude Moore (1917). An Old New England School: A History of Phillips Academy Andover. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Harvard Alumni Association (1910). Harvard University Directory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Harvard Class of 1862 (1912). Class Report, Class of 'Sixty Two, Harvard University, Fiftieth Anniversary. Cambridge: Harvard University. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association (1911). The Harvard Graduates Magazine, Volume XIX, 1910-1911. Vol. 19. Boston: Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Leonard, John W., ed. (1908). Men of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporaries. New York: L. R. Hamersly & Company. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- New England Historic Genealogical Society (1914). Vital Records of Cambridge, Massachusetts to the Year 1850. Vol. 1. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Rhode Island Board of Education (1874). Forth Annual Report of the Board of Education, Together with the Twenty-ninth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Public Schools of Rhode Island, January 1874. Providence, RI: Rhode Island Board of Education. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- School Committee of the City of Newport, Rhode Island (1901). Annual Report of the School Committee of the City of Newport, R. I., Together with the Report of the Head-Master of the Rogers High School and the Thirty-sixth annual report of the Superintendent of Public Schools, 1900-1901. Newport, RI: School Committee of the City of Newport, Rhode Island. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Trustees of Phillips Academy. "John Palfrey P'21". Andover. Trustees of Phillips Academy. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.