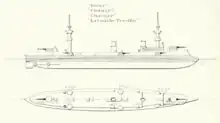

Sister ship Amiral Charner at anchor, c. 1897 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Bruix |

| Namesake | Étienne Eustache Bruix |

| Builder | Arsenal de Rochefort |

| Laid down | September 1890 |

| Launched | 2 August 1894 |

| Commissioned | 1 December 1896 |

| Stricken | 21 June 1920 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 21 June 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Amiral Charner-class armored cruiser |

| Displacement | 4,748 t (4,673 long tons) |

| Length | 110.2 m (361 ft 7 in) |

| Beam | 14.04 m (46 ft 1 in) |

| Draught | 6.06 m (19 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 screws; 2 × triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Range | 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 16 officers and 378 enlisted men |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

Bruix was one of four Amiral Charner-class armored cruisers built for the French Navy (Marine Navale)in the 1890s. She served in the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean, and in the Far East before World War I. In 1902 she aided survivors of the devastating eruption of Mount Pelée on the island of Martinique and spent several years as guardship at Crete, protecting French interests in the region in the early 1910s.

At the beginning of the war in August 1914, Bruix was assigned to protect troop convoys from French North Africa to France before she was transferred to the Atlantic to support Allied operations against the German colony of Kamerun in September. She was briefly assigned to support Allied operations in the Dardanelles in early 1915 before she began patrolling the Aegean Sea and Greek territorial waters.

The ship was decommissioned in Greece at the beginning of 1918 and recommissioned after the end of the war in November for service in the Black Sea against the Bolsheviks. Bruix returned home later in 1919 and was reduced to reserve before she was sold for scrap in 1921.

Design and description

The Amiral Charner-class ships were designed to be smaller and cheaper than the preceding armored cruiser design, the Dupuy de Lôme. Like the older ship, they were intended to fill the commerce-raiding strategy of the Jeune École.[1]

The ship measured 106.12 meters (348 ft 2 in) between perpendiculars, with a beam of 14.04 meters (46 ft 1 in). Bruix had a forward draft of 5.55 meters (18 ft 3 in) and drew 6.06 meters (19 ft 11 in) aft. She displaced 4,748 metric tons (4,673 long tons) at normal load and 4,990 metric tons (4,910 long tons) at deep load.[2]

The Amiral Charner class had two 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, each driving a single propeller shaft. Steam for the engines was provided by 16 Belleville boilers and they were rated at a total of 9,000 metric horsepower (6,600 kW) using forced draught. Bruix had a designed speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph), but only reached a maximum speed of 18.37 knots (34.02 km/h; 21.14 mph) from 9,107 metric horsepower (6,698 kW) during sea trials on 15 September 1896. The ship carried up to 535 metric tons (527 long tons; 590 short tons) of coal and could steam for 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[3]

The ships of the Amiral Charner class had a main armament that consisted of two Canon de 194 mm Modèle 1887 guns that were mounted in single gun turrets, one each fore and aft of the superstructure. Their secondary armament comprised six Canon de 138.6 mm Modèle 1887 guns, each in single gun turrets on each broadside. For anti-torpedo boat defense, they carried four 65 mm (2.6 in) guns, four 47-millimeter (1.9 in) and eight 37-millimeter (1.5 in) five-barreled revolving Hotchkiss guns. They were also armed with four 450-millimeter (17.7 in) pivoting torpedo tubes; two mounted on each broadside above water.[4]

The side of the Amiral Charner class was generally protected by 92 millimeters (3.6 in) of steel armor, from 1.3 meters (4 ft 3 in) below the waterline to 2.5 meters (8 ft 2 in) above it. The bottom 20 centimeters (7.9 in) tapered in thickness and the armor at the ends of the ships thinned to 60 millimeters (2.4 in). The curved protective deck had a thickness of 40 millimeters (1.6 in) along its centerline that increased to 50 millimeters (2.0 in) at its outer edges. Protecting the boiler rooms, engine rooms, and magazines below it was a thin splinter deck. A watertight internal cofferdam, filled with cellulose, ran the length of the ship from the protective deck[5] to a height of 1.2 meters (4 ft) above the waterline.[6] The ship's conning tower and turrets were protected by 92 millimeters of armor.[5]

Construction and career

Bruix, named after Admiral Étienne Eustache Bruix,[7] was laid down at the Arsenal de Rochefort on 9 November 1891. She was launched on 2 August 1894 and commissioned for trials on 15 April 1896. The ship was temporarily assigned to the Northern Squadron (Escadre du Nord) on 24 November for the visit of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his wife to Dunkerque on 5–9 October. The ship's steering broke down on 7 October and she had to return to Rochefort for repairs. Trials lasted until early December and Bruix was officially commissioned on 15 December and assigned to the Northern Squadron.[8]

On 18 August 1897, together with the protected cruiser Surcouf, she escorted the armored cruiser Pothuau that carried President Félix Faure on a state visit to Russia. Shortly after departure, Bruix fractured a piston rod in her port engine which forced her to return to port. Her repairs and armament trials lasted until January 1898, although the last of the trials was not completed until 25 February. Bruix was then assigned to the Far Eastern Squadron where she was based at Saigon, French Indochina until October,[9] although she made a port visit to Manila, the Philippines, on 5 May after the American victory in the Battle of Manila Bay.[10] While returning home in November, she damaged her starboard propeller on the 20th while transiting the Suez Canal. The ship reached Toulon on the 28th and was under repair until January 1899 before rejoining the Northern Squadron on 3 February.[11]

Bruix made port visits in Spain and Portugal in June before another piston rod was damaged on the 7th. She began a refit on 20 September that lasted until 4 November that modified her for service as a flagship. On 20 November the ship became the flagship of a cruiser division. In 1901 she participated in the annual fleet maneuvers with the rest of the Northern Squadron. During this training the British steamer SS Paddington collided with the ship, lightly damaging the plating of her armored ram on 27 June. Bilge keels were fitted to Bruix in November–December and she remained at the dockyard until 10 January 1902 to evaluate the operation of her turrets. The ship was assigned to the Atlantic Division in April and visited several Spanish ports during the month and into May.[11]

After the devastating eruption of Mount Pelée on 5 May, Bruix, now the flagship of Rear Admiral (contre-amiral) Palma Gourdon,[12] was ordered to Fort-de-France to render assistance to the survivors where she remained until 19 August.[11] On 30 November Rear Admiral Joseph Bugard hoisted his flag aboard Bruix.[13] The ship spent most of the next several years either commissioned with a reduced complement or assigned to the reserve. The ship was reactivated in late 1906 for service with the Far Eastern Squadron and departed Toulon on 15 November, accompanied by her sister ship Chanzy. They arrived at Saigon on 10 January 1907 and Bruix was in Nagasaki, Japan when Chanzy ran aground off the Chinese coast on 20 May. The ship then participated in the unsuccessful effort to rescue her sister. Bruix spent most of her tour in the Far East showing the flag in Russia, China and Japan and departed for home on 26 April 1909. While passing through the Suez Canal, she accidentally collided with the Italian steamer SS Nilo before arriving at Toulon on 2 August. She began an overhaul several weeks later that was repeatedly delayed by labor shortages at the dockyard. She was finally towed to the dockyard at Bizerte, in French North Africa, in June 1911 and her overhaul was completed in January 1912.[14]

Briefly assigned to the reserve, Bruix was recommissioned on 13 May for service with the Levant Division as the guardship for Crete. She relieved her sister Amiral Charner at Souda Bay on 9 July and spent the next two years in the Levant.[14] During the Italo-Turkish War, her captain protested the bombardment of fleeing Turkish troops near the port of Kalkan on 3 October by the protected cruiser Coatit as a breach of international law.[15] On 8 November the ship assisted in the refloating of the Russian protected cruiser Oleg. Although formally assigned to the Tunisian Squadron on 13 January 1913, Bruix remained in the Levant. Later in the year, she assisted in the salvage of the steamer SS Sénégal that had struck a mine at Smyrna, Turkey, that had been laid by the Italians during the war.[14] In March 1914 Bruix escorted William, Prince of Albania during his voyage from Trieste to Durazzo, Albania to take up his throne.[16] The ship returned to Bizerta on 25 April 1914 and began a refit that lasted until July.[14]

When World War I began in August, she was assigned to escort convoys between Morocco and France and general patrols together with her sisters Latouche-Tréville and Amiral Charner. Bruix was sent to support the Allied campaign against Kamerun in September and bombarded several small towns as part of her contribution before returning home later in the year.[17] After several short refits, Bruix was assigned to the Dardanelles squadron in February 1915 although the ship spent most of her time patrolling the Aegean. On 31 January 1918, she was placed in reserve at Salonika. Bruix was recommissioned on 29 November and transferred to Constantinople where she was assigned to the armored cruiser division of the 2nd Squadron on 2 December. Between March and May 1919 she patrolled the Black Sea as part of the Allied intervention against the Bolsheviks and took part in the evacuation of German and Allied troops from Nikolaev, Ukraine in March and from Odessa in April. Her crew did not participate in the mutiny that occurred aboard some French ships in Sevastopol, Crimea in April. Bruix departed the Black Sea for Constantinople on 5 May and then sailed for Toulon on 22 May where she was assigned to the reserve upon arrival. Proposals that she be converted into an accommodation ship or a merchant ship were judged impractical and she was stricken from the Navy List on 21 June 1920. Bruix was sold for scrap a year later, to the day, together with two other obsolete warships, for the price of 436,000 francs.[14]

Notes

- ↑ Feron, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Feron, p. 15

- ↑ Feron, pp. 15, 17, 25

- ↑ Feron, pp. 11, 15

- 1 2 Feron, pp. 12, 15

- ↑ Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 304

- ↑ Silverstone, p. ?

- ↑ Feron, p. 25

- ↑ Feron, pp. 25, 27

- ↑ Cooling, p. 95

- 1 2 3 Feron, p. 27

- ↑ Naval Notes June 1902, p. 822

- ↑ Naval Notes December 1902, p. 1603

- 1 2 3 4 5 Feron, p. 28

- ↑ Beehler, pp. 94–95

- ↑ Heaton-Armstrong, Belfield, & Destani, p. 17

- ↑ Corbett, pp. 264–65, 273–74, 368, 370, 397

Bibliography

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin (2000). USS Olympia: Herald of Empire. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-148-3.

- Corbett, Julian. Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd, reprint of the 1938 ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-256-X.

- Heaton-Armstrong, Duncan; Belfield, Gervase & Destani, Bejtullah D. (2005). The Six Month Kingdom: Albania 1914. London: I.B. Tauris, in association with the Centre for Albanian Studies. ISBN 1-85043-761-0.

- Feron, Luc (2014). "The Armoured Cruisers of the Amiral Charner Class". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2014. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-236-8.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. Royal United Services Institute. 46 (292). June 1902.

- "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. Royal United Services Institute. 46 (298). December 1902.

- Roksund, Arne (2007). The Jeune École: The Strategy of the Weak. History of Warfare. Vol. 43. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15723-1.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.