Gallium compounds are compounds containing the element gallium. These compounds are found primarily in the +3 oxidation state. The +1 oxidation state is also found in some compounds, although it is less common than it is for gallium's heavier congeners indium and thallium. For example, the very stable GaCl2 contains both gallium(I) and gallium(III) and can be formulated as GaIGaIIICl4; in contrast, the monochloride is unstable above 0 °C, disproportionating into elemental gallium and gallium(III) chloride. Compounds containing Ga–Ga bonds are true gallium(II) compounds, such as GaS (which can be formulated as Ga24+(S2−)2) and the dioxan complex Ga2Cl4(C4H8O2)2.[1] There are also compounds of gallium with negative oxidation states, ranging from -5 to -1, most of these compounds being magnesium gallides (MgxGay).

Aqueous chemistry

Strong acids dissolve gallium, forming gallium(III) salts such as Ga(NO

3)

3 (gallium nitrate). Aqueous solutions of gallium(III) salts contain the hydrated gallium ion, [Ga(H

2O)

6]3+

.[2]: 1033 Gallium(III) hydroxide, Ga(OH)

3, may be precipitated from gallium(III) solutions by adding ammonia. Dehydrating Ga(OH)

3 at 100 °C produces gallium oxide hydroxide, GaO(OH).[3]: 140–141

Alkaline hydroxide solutions dissolve gallium, forming gallate salts (not to be confused with identically named gallic acid salts) containing the Ga(OH)−

4 anion.[4][2]: 1033 [5] Gallium hydroxide, which is amphoteric, also dissolves in alkali to form gallate salts.[3]: 141 Although earlier work suggested Ga(OH)3−

6 as another possible gallate anion,[6] it was not found in later work.[5]

Oxides and chalcogenides

_oxide_crystal.jpg.webp)

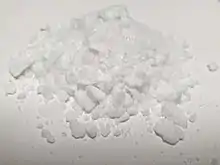

Gallium reacts with the chalcogens only at relatively high temperatures. At room temperature, gallium metal is not reactive with air and water because it forms a passive, protective oxide layer. At higher temperatures, however, it reacts with atmospheric oxygen to form gallium(III) oxide, Ga

2O

3.[4] Reducing Ga

2O

3 with elemental gallium in vacuum at 500 °C to 700 °C yields the dark brown gallium(I) oxide, Ga

2O.[3]: 285 Ga

2O is a very strong reducing agent, capable of reducing H

2SO

4 to H

2S.[3]: 207 It disproportionates at 800 °C back to gallium and Ga

2O

3.[7]

Gallium(III) sulfide, Ga

2S

3, has 3 possible crystal modifications.[7]: 104 It can be made by the reaction of gallium with hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) at 950 °C.[3]: 162 Alternatively, Ga(OH)

3 can be used at 747 °C:[8]

- 2 Ga(OH)

3 + 3 H

2S → Ga

2S

3 + 6 H

2O

Reacting a mixture of alkali metal carbonates and Ga

2O

3 with H

2S leads to the formation of thiogallates containing the [Ga

2S

4]2−

anion. Strong acids decompose these salts, releasing H

2S in the process.[7]: 104–105 The mercury salt, HgGa

2S

4, can be used as a phosphor.[9]

Gallium also forms sulfides in lower oxidation states, such as gallium(II) sulfide and the green gallium(I) sulfide, the latter of which is produced from the former by heating to 1000 °C under a stream of nitrogen.[7]: 94

The other binary chalcogenides, Ga

2Se

3 and Ga

2Te

3, have the zincblende structure. They are all semiconductors but are easily hydrolysed and have limited utility.[7]: 104

Nitrides and pnictides

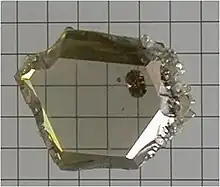

_2%22_wafer.jpg.webp)

Gallium reacts with ammonia at 1050 °C to form gallium nitride, GaN. Gallium also forms binary compounds with phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony: gallium phosphide (GaP), gallium arsenide (GaAs), and gallium antimonide (GaSb). These compounds have the same structure as ZnS, and have important semiconducting properties.[2]: 1034 GaP, GaAs, and GaSb can be synthesized by the direct reaction of gallium with elemental phosphorus, arsenic, or antimony.[7]: 99 They exhibit higher electrical conductivity than GaN.[7]: 101 GaP can also be synthesized by reacting Ga

2O with phosphorus at low temperatures.[10]

Gallium forms ternary nitrides; for example:[7]: 99

- Li

3Ga + N

2 → Li

3GaN

2

Similar compounds with phosphorus and arsenic are possible: Li

3GaP

2 and Li

3GaAs

2. These compounds are easily hydrolyzed by dilute acids and water.[7]: 101

Halides

Gallium(III) oxide reacts with fluorinating agents such as HF or F

2 to form gallium(III) fluoride, GaF

3. It is an ionic compound strongly insoluble in water. However, it dissolves in hydrofluoric acid, in which it forms an adduct with water, GaF

3·3H

2O. Attempting to dehydrate this adduct forms GaF

2OH·nH

2O. The adduct reacts with ammonia to form GaF

3·3NH

3, which can then be heated to form anhydrous GaF

3.[3]: 128–129

Gallium trichloride is formed by the reaction of gallium metal with chlorine gas.[4] Unlike the trifluoride, gallium(III) chloride exists as dimeric molecules, Ga

2Cl

6, with a melting point of 78 °C. Eqivalent compounds are formed with bromine and iodine, Ga

2Br

6 and Ga

2I

6.[3]: 133

Like the other group 13 trihalides, gallium(III) halides are Lewis acids, reacting as halide acceptors with alkali metal halides to form salts containing GaX−

4 anions, where X is a halogen. They also react with alkyl halides to form carbocations and GaX−

4.[3]: 136–137

When heated to a high temperature, gallium(III) halides react with elemental gallium to form the respective gallium(I) halides. For example, GaCl

3 reacts with Ga to form GaCl:

- 2 Ga + GaCl

3 ⇌ 3 GaCl (g)

At lower temperatures, the equilibrium shifts toward the left and GaCl disproportionates back to elemental gallium and GaCl

3. GaCl can also be produced by reacting Ga with HCl at 950 °C; the product can be condensed as a red solid.[2]: 1036

Gallium(I) compounds can be stabilized by forming adducts with Lewis acids. For example:

- GaCl + AlCl

3 → Ga+

[AlCl

4]−

The so-called "gallium(II) halides", GaX

2, are actually adducts of gallium(I) halides with the respective gallium(III) halides, having the structure Ga+

[GaX

4]−

. For example:[4][2]: 1036 [11]

- GaCl + GaCl

3 → Ga+

[GaCl

4]−

Hydrides

Like aluminium, gallium also forms a hydride, GaH

3, known as gallane, which may be produced by reacting lithium gallanate (LiGaH

4) with gallium(III) chloride at −30 °C:[2]: 1031

- 3 LiGaH

4 + GaCl

3 → 3 LiCl + 4 GaH

3

In the presence of dimethyl ether as solvent, GaH

3 polymerizes to (GaH

3)

n. If no solvent is used, the dimer Ga

2H

6 (digallane) is formed as a gas. Its structure is similar to diborane, having two hydrogen atoms bridging the two gallium centers,[2]: 1031 unlike α-AlH

3 in which aluminium has a coordination number of 6.[2]: 1008

Gallane is unstable above −10 °C, decomposing to elemental gallium and hydrogen.[12]

Organogallium compounds

Organogallium compounds are of similar reactivity to organoindium compounds, less reactive than organoaluminium compounds, but more reactive than organothallium compounds.[13] Alkylgalliums are monomeric. Lewis acidity decreases in the order Al > Ga > In and as a result organogallium compounds do not form bridged dimers as organoaluminium compounds do. Organogallium compounds are also less reactive than organoaluminium compounds. They do form stable peroxides.[14] These alkylgalliums are liquids at room temperature, having low melting points, and are quite mobile and flammable. Triphenylgallium is monomeric in solution, but its crystals form chain structures due to weak intermolecluar Ga···C interactions.[13]

Gallium trichloride is a common starting reagent for the formation of organogallium compounds, such as in carbogallation reactions.[15] Gallium trichloride reacts with lithium cyclopentadienide in diethyl ether to form the trigonal planar gallium cyclopentadienyl complex GaCp3. Gallium(I) forms complexes with arene ligands such as hexamethylbenzene. Because this ligand is quite bulky, the structure of the [Ga(η6-C6Me6)]+ is that of a half-sandwich. Less bulky ligands such as mesitylene allow two ligands to be attached to the central gallium atom in a bent sandwich structure. Benzene is even less bulky and allows the formation of dimers: an example is [Ga(η6-C6H6)2] [GaCl4]·3C6H6.[13]

See also

- Organogallium chemistry

- Category:Gallium compounds

- Aluminium compounds

- Indium compounds

- Germanium compounds

References

- ↑ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 240

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils; Holleman, Arnold Frederick (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Downs, Anthony John (1993). Chemistry of aluminium, gallium, indium, and thallium. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7514-0103-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Eagleson, Mary, ed. (1994). Concise encyclopedia chemistry. Walter de Gruyter. p. 438. ISBN 978-3-11-011451-5.

- 1 2 Sipos, P. L.; Megyes, T. N.; Berkesi, O. (2008). "The Structure of Gallium in Strongly Alkaline, Highly Concentrated Gallate Solutions—a Raman and 71

Ga

-NMR Spectroscopic Study". J Solution Chem. 37 (10): 1411–1418. doi:10.1007/s10953-008-9314-y. S2CID 95723025. - ↑ Hampson, N. A. (1971). Harold Reginald Thirsk (ed.). Electrochemistry—Volume 3: Specialist periodical report. Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-85186-027-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Greenwood, N. N. (1962). Harry Julius Emeléus; Alan G. Sharpe (eds.). Advances in inorganic chemistry and radiochemistry. Vol. 5. Academic Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-12-023605-3.

- ↑ Madelung, Otfried (2004). Semiconductors: data handbook (3rd ed.). Birkhäuser. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-3-540-40488-0.

- ↑ Krausbauer, L.; Nitsche, R.; Wild, P. (1965). "Mercury gallium sulfide, HgGa

2S

4, a new phosphor". Physica. 31 (1): 113–121. Bibcode:1965Phy....31..113K. doi:10.1016/0031-8914(65)90110-2. - ↑ Michelle Davidson (2006). Inorganic Chemistry. Lotus Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-81-89093-39-6.

- ↑ Arora, Amit (2005). Text Book Of Inorganic Chemistry. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 389–399. ISBN 978-81-8356-013-9.

- ↑ Downs, Anthony J.; Pulham, Colin R. (1994). Sykes, A. G. (ed.). Advances in Inorganic Chemistry. Vol. 41. Academic Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-12-023641-1.

- 1 2 3 Greenwoood and Earnshaw, pp. 262–5

- ↑ Uhl, W. and Halvagar, M. R.; et al. (2009). "Reducing Ga-H and Ga-C Bonds in Close Proximity to Oxidizing Peroxo Groups: Conflicting Properties in Single Molecules". Chemistry: A European Journal. 15 (42): 11298–11306. doi:10.1002/chem.200900746. PMID 19780106.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Amemiya, Ryo (2005). "GaCl3 in Organic Synthesis". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2005 (24): 5145–5150. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200500512.