_(W3).svg.png.webp)

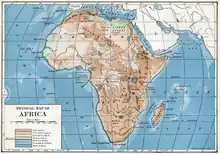

Africa is a continent comprising 63 political territories, representing the largest of the great southward projections from the main mass of Earth's surface.[1] Within its regular outline, it comprises an area of 30,368,609 km2 (11,725,385 sq mi), excluding adjacent islands. Its highest mountain is Kilimanjaro; its largest lake is Lake Victoria.

Separated from Europe by the Mediterranean Sea and from much of Asia by the Red Sea, Africa is joined to Asia at its northeast extremity by the Isthmus of Suez (which is transected by the Suez Canal), 130 km (81 mi) wide. For geopolitical purposes, the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt – east of the Suez Canal – is often considered part of Africa. From the most northerly point, Ras ben Sakka in Tunisia, at 37°21′ N, to the most southerly point, Cape Agulhas in South Africa, 34°51′15″ S, is a distance approximately of 8,000 km (5,000 mi); from Cap-Vert, 17°31′13″W, the westernmost point, to Ras Hafun in the Somali Puntland region, in the Horn of Africa, 51°27′52″ E, the most easterly projection, is a distance (also approximately) of 7,400 km (4,600 mi).[1]

The main structural lines of the continent show both the east-to-west direction characteristic, at least in the eastern hemisphere, of the more northern parts of the world, and the north-to-south direction seen in the southern peninsulas. Africa is thus mainly composed of two segments at right angles, the northern running from east to west, and the southern from north to south.[1]

Main features

.jpg.webp)

The average elevation of the continent approximates closely to 600 m (2,000 ft) above sea level, roughly near to the mean elevation of both North and South America, but considerably less than that of Asia, 950 m (3,120 ft). In contrast with other continents, it is marked by the comparatively small area of either very high or very low ground, lands under 180 m (590 ft) occupying an unusually small part of the surface; while not only are the highest elevations inferior to those of Asia or South America, but the area of land over 3,000 m (9,800 ft) is also quite insignificant, being represented almost entirely by individual peaks and mountain ranges. Moderately elevated tablelands are thus the characteristic feature of the continent, though the surface of these is broken by higher peaks and ridges. (So prevalent are these isolated peaks and ridges that a specialised term—Inselberg-Landschaft, island mountain landscape—has been adopted in Germany to describe this kind of country, thought to be in great part the result of wind action.)[1]

As a general rule, the higher tablelands lie to the east and south, while a progressive diminution in altitude towards the west and north is observable. Apart from the lowlands and the Atlas mountain range, the continent may be divided into two regions of higher and lower plateaus, the dividing line (somewhat concave to the northwest) running from the middle of the Red Sea to about 6 degrees south on the west coast.[1]

Africa can be divided into a number of geographic zones:

- The coastal plains—often fringed seawards by mangrove swamps—never stretching far from the coast, apart from the lower courses of streams. Recent alluvial flats are found chiefly in the delta of the more important rivers. Elsewhere, the coastal lowlands merely form the lowest steps of the system of terraces that constitutes the ascent to the inner plateaus.

- The Atlas range—orthographically distinct from the rest of the continent, being unconnected with and separated from the south by a depressed and desert area (the Sahara).[1]

Plateau region

There are many plateaus in Africa.

The high southern and eastern plateaus, rarely falling below 600 m (2,000 ft), have a mean elevation of about 1,000 m (3,300 ft). The South African plateau, as far as about 12° S, is bounded east, west and south by bands of high ground which fall steeply to the coasts. On this account South Africa has a general resemblance to an inverted saucer. Due south, the plateau rim is formed by three parallel steps with level ground between them. The largest of these level areas, the Great Karoo, is a dry, barren region, and a large tract of the plateau proper is of a still more arid character and is known as the Kalahari Desert.[1]

The South African plateau is connected towards East African plateau, with probably a slightly greater average elevation, and marked by some distinct features. It is formed by a widening out of the eastern axis of high ground, which becomes subdivided into a number of zones running north and south and consisting in turn of ranges, tablelands and depressions. The most striking feature is the existence of two great lines of depression, due largely to the subsidence of whole segments of the Earth's crust, the lowest parts of which are occupied by vast lakes. Towards the south the two lines converge and give place to one great valley (occupied by Lake Nyasa), the southern part of which is less distinctly due to rifting and subsidence than the rest of the system.[1]

Farther north the western hollow, known as the Albertine Rift, is occupied for more than half its length by water, forming the Great Lakes of Tanganyika, Kivu, Lake Edward and Lake Albert, the first-named over 400 miles (640 km) long and the longest freshwater lake in the world. Associated with these great valleys are a number of volcanic peaks, the greatest of which occur on a meridional line east of the eastern trough. The eastern branch of the East African Rift, contains much smaller lakes, many of them brackish and without outlet, the only one comparable to those of the western trough being Lake Turkana or Basso Norok.[1]

A short distance east of this rift valley is Mount Kilimanjaro – with its two peaks Kibo and Mawenzi, the latter being 5,889 m (19,321 ft), and the culminating point of the whole continent – and Mount Kenya, which is 5,184 m (17,008 ft). Hardly less important is the Ruwenzori Range, over 5,060 m (16,600 ft), which lies east of the western trough. Other volcanic peaks rise from the floor of the valleys, some of the Kirunga (Mfumbiro) group, north of Lake Kivu, being still partially active.[1] This could cause most of the cities and states to be flooded with lava and ash.

The third division of the higher region of Africa is formed by the Ethiopian Highlands, a rugged mass of mountains forming the largest continuous area of its altitude in the whole continent, little of its surface falling below 1,500 m (4,900 ft), while the summits reach heights of 4400 m to 4550 m. This block of country lies just west of the line of the great East African Trough, the northern continuation of which passes along its eastern escarpment as it runs up to join the Red Sea. There is, however, in the centre a circular basin occupied by Lake Tsana.[1]

Both in the east and west of the continent the bordering highlands are continued as strips of plateau parallel to the coast, the Ethiopian mountains being continued northwards along the Red Sea coast by a series of ridges reaching in places a height of 2,000 m (6,600 ft). In the west the zone of high land is broader but somewhat lower. The most mountainous districts lie inland from the head of the Gulf of Guinea (Adamawa, etc.), where heights of 1,800 to 2,400 m (5,900 to 7,900 ft) are reached. Exactly at the head of the gulf the great peak of the Cameroon, on a line of volcanic action continued by the islands to the south-west, has a height of 4,075 m (13,369 ft), while Clarence Peak, in Fernando Po, the first of the line of islands, rises to over 2,700 m (8,900 ft). Towards the extreme west the Futa Jallon highlands form an important diverging point of rivers, but beyond this, as far as the Atlas chain, the elevated rim of the continent is almost wanting.[1]

Plains

Much of Africa is made up of plains of the pediplain and etchplain type often occurring as steps.[2][3] The etchplains are commonly associated with laterite soil and inselbergs.[2] Inselberg-dotted plains are common in Africa including Tanzania,[4] the Anti-Atlas of Morocco,[2] Namibia,[5] and the interior of Angola.[6] One of the most wideaspread plain is the African Surface, a composite etchplain occurring across much of the continent.[7][2][8]

The area between the east and west coast highlands, which north of 17° N is mainly desert, is divided into separate basins by other bands of high ground, one of which runs nearly centrally through North Africa in a line corresponding roughly with the curved axis of the continent as a whole. The best marked of the basins so formed (the Congo Basin) occupies a circular area bisected by the equator, once probably the site of an inland sea.[1]

Running along the south of desert is the plains region known as the Sahel.

The arid region, the Sahara — the largest hot desert in the world, covering 9,000,000 km2 (3,500,000 sq mi) — extends from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. Though generally of slight elevation, it contains mountain ranges with peaks rising to 2,400 m (7,900 ft) Bordered N.W. by the Atlas range, to the northeast a rocky plateau separates it from the Mediterranean; this plateau gives place at the extreme east to the delta of the Nile. That river (see below) pierces the desert without modifying its character. The Atlas range, the north-westerly part of the continent, between its seaward and landward heights encloses elevated steppes in places 160 km (99 mi) broad. From the inner slopes of the plateau numerous wadis take a direction towards the Sahara. The greater part of that now desert region is, indeed, furrowed by old water-channels.[1]

Mountains

The mountains are an exception to Africa's general landscape. Geographers came up with the idea of "high Africa" and "low Africa" to help distinguish the difference in Geography; "high Africa" extending from Ethiopia down south to South Africa and the Cape of Good Hope while "low Africa" representing the plains of the rest of the continent.[9] The following table gives the details of the chief mountains and ranges of the continent:[1]

|

Rivers

From the outer margin of the African plateaus, a large number of streams run to the sea with comparatively short courses, while the larger rivers flow for long distances on the interior highlands, before breaking through the outer ranges. The main drainage of the continent is to the north and west, or towards the basin of the Atlantic Ocean.[1]

To the main African rivers belong: Nile (the longest river of Africa), Congo (river with the highest water discharge on the continent) and the Niger, which flows half of its length through the arid areas. The largest lakes are the following: Lake Victoria (Lake Ukerewe), Lake Chad, in the centre of the continent, Lake Tanganyika, lying between the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Tanzania and Zambia. There is also the considerably large Lake Malawi stretching along the eastern border of Malawi. There are also numerous water dams throughout the continent: Kariba on the river of Zambezi, Asuan in Egypt on the river of Nile, and Akosombo, the continent's biggest dam on the Volta River in Ghana (Fobil 2003). The high lake plateau of the African Great Lakes region contains the headwaters of both the Nile and the Congo.

The break-up of Gondwana in Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic times led to a major reorganization of the river courses of various large African rivers including the Congo, Niger, Nile, Orange, Limpopo and Zambezi rivers.[10]

Flowing to the Mediterranean Sea

The upper Nile receives its chief supplies from the mountainous region adjoining the Central African trough in the neighborhood of the equator. From there, streams pour eastward into Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa (covering over 26,000 square m.), and to the west and north into Lake Edward and Lake Albert. To the latter of these, the effluents of the other two lakes add their waters. Issuing from there, the Nile flows northward, and between the latitudes of 7 and 10 degrees north it traverses a vast marshy level, where its course is liable to being blocked by floating vegetation. After receiving the Bahr-el-Ghazal from the west and the Sobat, Blue Nile and Atbara from the Ethiopian Highlands (the chief gathering ground of the flood-water), it separates the great desert with its fertile watershed, and enters the Mediterranean at a vast delta.[1]

Flowing to the Atlantic Ocean

The most remote head-stream of the Congo is the Chambezi, which flows southwest into the marshy Lake Bangweulu. From this lake issues the Congo, known in its upper course by various names. Flowing first south, it afterwards turns north through Lake Mweru and descends to the forest-clad basin of west equatorial Africa. Traversing this in a majestic northward curve, and receiving vast supplies of water from many great tributaries, it finally turns southwest and cuts a way to the Atlantic Ocean through the western highlands. The area of the Congo basin is greater than that of any other river except the Amazon, while the African inland drainage area is greater than that of any continent but Asia, where the corresponding area is 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi).[1]

West of Lake Chad is the basin of the Niger, the third major river of Africa. With its principal source in the far west, it reverses the direction of flow exhibited by the Nile and Congo,[1] and ultimately flows into the Atlantic — a fact that eluded European geographers for many centuries. An important branch, however — the Benue — flows from the southeast.

These four river basins occupy the greater part of the lower plateaus of North and West Africa — the remainder consists of arid regions watered only by intermittent streams that do not reach the sea.[1]

Of the remaining rivers of the Atlantic basin, the Orange, in the extreme south, brings the drainage from the Drakensberg on the opposite side of the continent, while the Kunene, Kwanza, Ogowe and Sanaga drain the west coastal highlands of the southern limb; the Volta, Komoe, Bandama, Gambia and Senegal the highlands of the western limb. North of the Senegal, for over 1,500 km (930 mi) of coast, the arid region reaches to the Atlantic. Farther north are the streams, with comparatively short courses, reaching the Atlantic and Mediterranean from the Atlas mountains.[1]

Flowing to the Indian Ocean

Of the rivers flowing to the Indian Ocean, the only one draining any large part of the interior plateaus is the Zambezi, whose western branches rise in the western coastal highlands. The main stream has its rise in 11°21′3″ S 24°22′ E, at an elevation of 1,500 m (4,900 ft). It flows to the west and south for a considerable distance before turning eastward. All the largest tributaries, including the Shire, the outflow of Lake Nyasa, flow down the southern slopes of the band of high ground stretching across the continent from 10° to 12° S. In the southwest, the Zambezi system interlaces with that of the Taukhe (or Tioghe), from which it at times receives surplus water. The rest of the water of the Taukhe, known in its middle course as the Okavango, is lost in a system of swamps and saltpans that was formerly centred in Lake Ngami, now dried up.[1]

Farther south, the Limpopo drains a portion of the interior plateau, but breaks through the bounding highlands on the side of the continent nearest its source. The Rovuma, Rufiji and Tana principally drain the outer slopes of the African Great Lakes highlands.[1]

In the Horn region to the north, the Jubba and the Shebelle rivers begin in the Ethiopian Highlands. These rivers mainly flow southwards, with the Jubba emptying in the Indian Ocean. The Shebelle River reaches a point to the southwest. After that, it consists of swamps and dry reaches before finally disappearing in the desert terrain near the Jubba River. Another large stream, the Hawash, rising in the Ethiopian mountains, is lost in a saline depression near the Gulf of Aden.[1]

Inland basins

Between the basins of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, there is an area of inland drainage along the centre of the Ethiopian plateau, directed chiefly into the lakes in the Great Rift Valley. The largest river is the Omo, which, fed by the rains of the Ethiopian highlands, carries down a large body of water into Lake Turkana. The rivers of Africa are generally obstructed either by bars at their mouths, or by cataracts at no great distance upstream. But when these obstacles have been overcome, the rivers and lakes afford a vast network of navigable waters.[1]

North of the Congo basin, and separated from it by a broad undulation of the surface, is the basin of Lake Chad — a flat-shored, shallow lake filled principally by the Chari coming from the southeast.[1]

Lakes

The principal lakes of Africa are situated in the African Great Lakes plateau. The lakes found within the Great Rift Valley have steep sides and are very deep. This is the case with the two largest of the type, Tanganyika and Nyasa, the latter with depths of 800 m (2,600 ft).

Others, however, are shallow, and hardly reach the steep sides of the valleys in the dry season. Such are Lake Rukwa, in a subsidiary depression north of Nyasa, and Eiassi and Manyara in the system of the Great Rift Valley. Lakes of the broad type are of moderate depth, the deepest sounding in Lake Victoria being under 90 m (300 ft).[1]

Besides the African Great Lakes, the principal lakes on the continent are: Lake Chad, in the northern inland watershed; Bangweulu and Mweru, traversed by the head-stream of the Congo; and Lake Mai-Ndombe and Ntomba (Mantumba), within the great bend of that river. All, except possibly Mweru, are more or less shallow, and Lake Chad appears to be drying up.[1]

Divergent opinions have been held as to the mode of origin of the African Great Lakes, especially Tanganyika, which some geologists have considered to represent an old arm of the sea, dating from a time when the whole central Congo basin was under water; others holding that the lake water has accumulated in a depression caused by subsidence. The former view is based on the existence in the lake of organisms of a decidedly marine type. They include jellyfish, molluscs, prawns, crabs, etc.[1]

| Lake | Country | Area | Depth | Surface elevation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | ft | ||||

| Chad | Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria | 259 | 850 | ||

| Mai-Ndombe | Dem. Rep. Congo | 335 | 1,099 | ||

| Turkana | Kenya | 381 | 1,250 | ||

| Malawi | Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania | 501 | 1,644 | ||

| Albert | Dem. Rep. Congo, Uganda | 618 | 2,028 | ||

| Tanganyika | Tanzania, Dem. Rep Congo, Burundi, Zambia | 800 | 2,600 | ||

| Ngami | Botswana | 899 | 2,949 | ||

| Mweru | Dem. Rep. Congo, Zambia | 914 | 2,999 | ||

| Edward | Dem. Rep. Congo, Uganda | 916 | 3,005 | ||

| Bangweulu | Zambia | 1,128 | 3,701 | ||

| Victoria | Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya | 1,134 | 3,720 | ||

| Abaya | Ethiopia | 1,280 | 4,200 | ||

| Kivu | Dem. Rep. Congo, Rwanada | 1,472 | 4,829 | ||

| Tana | Ethiopia | 1,734 | 5,689 | ||

| Naivasha | Kenya | 1,870 | 6,140 | ||

Islands

With the exception of Madagascar, the African islands are small. Madagascar, with an area of 587,041 km2 (226,658 sq mi), is, after Greenland, New Guinea and Borneo, the fourth largest island on the Earth. It lies in the Indian Ocean, off the southeast coast of the continent, from which it is separated by the deep Mozambique Channel, 400 km (250 mi) wide at its narrowest point. Madagascar in its general structure, as in flora and fauna, forms a connecting link between Africa and southern Asia. East of Madagascar are the small islands of Mauritius and Réunion.[1] There are also islands in the Gulf of Guinea on which lies the Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe (islands of São Tomé and Príncipe). Part of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea is lying on the island of Bioko (with the capital Malabo and the town of Lubu) and the island of Annobón. Socotra lies E.N.E. of Cape Guardafui. Off the north-west coast are the Canary and Cape Verde archipelagoes. which, like some small islands in the Gulf of Guinea, are of volcanic origin.[1] The South Atlantic Islands of Saint Helena and Ascension are classed as Africa but are situated on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge half way to South America.

Climatic conditions

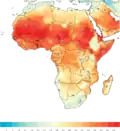

Lying almost entirely within the tropics, and equally to north and south of the equator, Africa does not show excessive variations of temperature.[1][11]

Great heat is experienced in the lower plains and desert regions of North Africa, removed by the great width of the continent from the influence of the ocean, and here, too, the contrast between day and night, and between summer and winter, is greatest. (The rarity of the air and the great radiation during the night cause the temperature in the Sahara to fall occasionally to freezing point.) Farther south, the heat is to some extent modified by the moisture brought from the ocean, and by the greater elevation of a large part of the surface, especially in East Africa, where the range of temperature is wider than in the Congo basin or on the Guinea coast. In the extreme north and south the climate is a warm temperate one, the northern countries being on the whole hotter and drier than those in the southern zone; the south of the continent being narrower than the north, the influence of the surrounding ocean is more felt.[1]

The most important climatic differences are due to variations in the amount of rainfall. The wide heated plains of the Sahara, and in a lesser degree the corresponding zone of the Kalahari in the south, have an exceedingly scanty rainfall, the winds which blow over them from the ocean losing part of their moisture as they pass over the outer highlands, and becoming constantly drier owing to the heating effects of the burning soil of the interior; while the scarcity of mountain ranges in the more central parts likewise tends to prevent condensation. In the inter-tropical zone of summer precipitation, the rainfall is greatest when the sun is vertical or soon after. It is therefore greatest of all near the equator, where the sun is twice vertical, and less in the direction of both tropics.[1]

The rainfall zones are, however, somewhat deflected from a due west-to-east direction, the drier northern conditions extending southwards along the east coast, and those of the south northwards along the west. Within the equatorial zone certain areas, especially on the shores of the Gulf of Guinea and in the upper Nile basin, have an intensified rainfall, but this rarely approaches that of the rainiest regions of the world. The rainiest district in all Africa is a strip of coastland west of Mount Cameroon, where there is a mean annual rainfall of about 10,000 mm (394 in) as compared with a mean of 11,600 mm (457 in) at Cherrapunji, in Meghalaya, India.[1]

The two distinct rainy seasons of the equatorial zone, where the sun is vertical at half-yearly intervals, become gradually merged into one in the direction of the tropics, where the sun is overhead but once. Snow falls on all the higher mountain ranges, and on the highest the climate is thoroughly Alpine.[1]

The countries bordering the Sahara are much exposed to a very dry wind, full of fine particles of sand, blowing from the desert towards the sea. Known in Egypt as the khamsin, on the Mediterranean as the sirocco, it is called on the Guinea coast the harmattan. This wind is not invariably hot; its great dryness causes so much evaporation that cold is not infrequently the result. Similar dry winds blow from the Kalahari Desert in the south. On the eastern coast the monsoons of the Indian Ocean are regularly felt, and on the southeast hurricanes are occasionally experienced.[1]

Health

The climate of Africa lends itself to certain environmental diseases, the most serious of which are: malaria, sleeping sickness and yellow fever. Malaria is the most deadly environmental disease in Africa. It is transmitted by a genus of mosquito (anopheles mosquito) native to Africa, and can be contracted over and over again. There is not yet a vaccine for malaria, which makes it difficult to prevent the disease from spreading in Africa. Recently, the dissemination of mosquito netting has helped lower the rate of malaria.

Yellow fever is a disease also transmitted by mosquitoes native to Africa. Unlike malaria, it cannot be contracted more than once. Like chicken pox, it is a disease that tends to be severe the later in life a person contracts the disease.[11]

Sleeping sickness, or African trypanosomiasis, is a disease that usually affects animals, but has been known to be fatal to some humans as well. It is transmitted by the tsetse fly and is found almost exclusively in Sub-Saharan Africa.[12] This disease has had a significant impact on African development not because of its deadly nature, like Malaria, but because it has prevented Africans from pursuing agriculture (as the sleeping sickness would kill their livestock).[11]

Extreme points

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Heawood, Edward; Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). "Africa". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–322.

- 1 2 3 4 Guillocheau, François; Simon, Brendan; Baby, Guillaume; Bessin, Paul; Robin, Cécile; Dauteuil, Olivier (2017). "Planation surfaces as a record of mantle dynamics: The case example of Africa" (PDF). Gondwana Research. 53: 82. Bibcode:2018GondR..53...82G. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2017.05.015.

- ↑ Coltorti, M.; Dramis, F.; Ollier, C.D (2007). "Planation surfaces in Northern Ethiopia". Geomorphology. 89 (3–4): 287–296. Bibcode:2007Geomo..89..287C. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.12.007.

- ↑ Sundborg, Å., & Rapp, A. (1986). Erosion and sedimentation by water: problems and prospects. Ambio, 215-225.

- ↑ "PRODUCTION OF AN AGRO.ECOLOGICAL ZONES MAP OF NAMIBIA (first approximation)" (PDF). nbri.org.na. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ↑ "DEVELOPMENT OF A SOIL AND TERRAIN MAP/DATABASE FOR ANGOLA" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- ↑ Burke, Kevin; Gunnell, Yanni (2008). The African Erosion Surface: A Continental-Scale Synthesis of Geomorphology, Tectonics, and Environmental Change over the Past 180 Million Years. The Geological Society of America. ISBN 978-0-8137-1201-7.

- ↑ Beauvais, A.; Ruffet, G.; Henócque, O.; Colin, F. (2008). "Chemical and physical erosion rhythms of the West African Cenozoic morphogenesis: The 39Ar-40Ar dating of supergene K-Mn oxides" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 113 (113): F04007. Bibcode:2008JGRF..113.4007B. doi:10.1029/2008JF000996. S2CID 14145710.

- ↑ Delehanty, James (2014). Africa, Fourth Edition. Indiana University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-253-01302-6.

- ↑ Goudie, A.S. (2005). "The drainage of Africa since the Cretaceous". Geomorphology. 67 (3–4): 437–456. Bibcode:2005Geomo..67..437G. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.11.008.

- 1 2 3 "Key Elements of Africa's Geographic Landscape and Climate Patterns" (PDF). The Saylor Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)". World Health Organization. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

Further reading

External links

Media related to Geography of Africa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Geography of Africa at Wikimedia Commons- "Africa". Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- "Regions of the African Union". UNEP/GRID-Arendal. Retrieved 1 January 2023.