Simone Weil | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Born | Simone Adolphine Weil 3 February 1909 Paris, France |

| Died | 24 August 1943 (aged 34) |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | École Normale Supérieure, University of Paris[1] (B.A., M.A.) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Marxism (early) Christian anarchism[2] Christian socialism[3] (late) Christian Mysticism Individualism[4] Modern Platonism[5] |

Main interests | Political philosophy, moral philosophy,[6] philosophy of religion, philosophy of science |

Notable ideas | Decreation (renouncing the gift of free will as a form of acceptance of everything that is independent of one's particular desires;[7] making "something created pass into the uncreated"),[8] uprootedness (déracinement), patriotism of compassion,[9] abolition of political parties, the unjust character of affliction (malheur), compassion must act in the area of metaxy[10] |

Simone Adolphine Weil (/ˈveɪ/ VAY,[11] French: [simɔn adɔlfin vɛj]; 3 February 1909 – 24 August 1943) was a French philosopher, mystic, and political activist. Since 1995, more than 2,500 scholarly works have been published about her, including close analyses and readings of her work.[12]

After her graduation from formal education, Weil became a teacher. She taught intermittently throughout the 1930s, taking several breaks because of poor health and in order to devote herself to political activism. Such work saw her assisting in the trade union movement, taking the side of the anarchists known as the Durruti Column in the Spanish Civil War, and spending more than a year working as a labourer, mostly in car factories, so that she could better understand the working class.

Weil became increasingly religious and inclined towards mysticism as her life progressed.[13] She wrote throughout her life, although most of her writings did not attract much attention until after her death. In the 1950s and 1960s, her work became famous in continental Europe and throughout the English-speaking world. Her thought has continued to be the subject of extensive scholarship across a wide range of fields.[14]

The mathematician André Weil was her brother.[15][16]

Early life

Weil was born in her parents' apartment in Paris on 3 February 1909, the daughter of Bernard Weil (1872–1955), a medical doctor from an agnostic Alsatian Jewish background, who moved to Paris after the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine, and Salomea "Selma" Reinherz (1879–1965), who was born into a Jewish family in Rostov-on-Don and raised in Belgium.[17] According to Osmo Pekonen, "the family name Weil came to be when many Levis in the Napoleonic era changed their names this way, by anagram."[18] Weil was a healthy baby for her first six months but then suffered a severe attack of appendicitis; thereafter, she struggled with poor health throughout her life. She was the younger of her parents' two children. Her brother was mathematician André Weil (1906–1998), with whom she would always enjoy a close relationship.[19] Their parents were fairly affluent and raised their children in an attentive and supportive atmosphere.[20]

Weil was distressed by her father having to leave home for several years after being drafted to serve in the First World War. Eva Fogelman, Robert Coles and several other scholars believe that this experience may have contributed to the exceptionally strong altruism which Weil displayed throughout her life.[21][22][23] From her childhood home, Weil acquired an obsession with cleanliness; in her later life she would sometimes speak of her "disgustingness" and think that others would see her this way, even though in her youth she had been considered highly attractive.[24] Weil was generally highly affectionate, but she almost always avoided any form of physical contact, even with female friends.[25]

According to her friend and biographer, Simone Pétrement, Weil decided early in life that she would need to adopt masculine qualities and sacrifice opportunities for love affairs in order to fully pursue her vocation to improve social conditions for the disadvantaged. From her late teenage years, Weil would generally disguise her "fragile beauty" by adopting a masculine appearance, hardly ever using makeup and often wearing men's clothes.[26][27]

Intellectual life

Weil was a precocious student, proficient in Ancient Greek by age 12. She later learned Sanskrit so that she could read the Bhagavad Gita in the original.[13] Like the Renaissance thinker Pico della Mirandola, her interests in other religions were universal, and she attempted to understand each religious tradition as an expression of transcendent wisdom.

As a teenager, Weil studied at the Lycée Henri IV under the tutelage of her admired teacher Émile Chartier, more commonly known as "Alain".[28] Her first attempt at the entrance examination for the École Normale Supérieure in June 1927 ended in failure, due to her low marks in history. In 1928 she was successful in gaining admission. She finished first in the exam for the certificate of "General Philosophy and Logic"; Simone de Beauvoir finished second.[29] During these years, Weil attracted much attention with her radical opinions. She was called the "Red virgin",[29] and even "The Martian" by her admired mentor.[30]

At the École Normale Supérieure, she studied philosophy, earning her DES (diplôme d'études supérieures, roughly equivalent to an M.A.) in 1931 with a thesis under the title "Science et perception dans Descartes" ("Science and Perception in Descartes").[31] She received her agrégation that same year.[32] Weil taught philosophy at a secondary school for girls in Le Puy and teaching was her primary employment during her short life.

Political activism

She often became involved in political action out of sympathy with the working class. In 1915, when she was only six years old, she refused sugar in solidarity with the troops entrenched along the Western Front. In 1919, at 10 years of age, she declared herself a Bolshevik. In her late teens, she became involved in the workers' movement. She wrote political tracts, marched in demonstrations and advocated workers' rights. At this time, she was a Marxist, pacifist and trade unionist. While teaching in Le Puy, she became involved in local political activity, supporting the unemployed and striking workers despite criticism. Weil never formally joined the French Communist Party, and in her twenties she became increasingly critical of Marxism. According to Pétrement, she was one of the first to identify a new form of oppression not anticipated by Marx, where élite bureaucrats could make life just as miserable for ordinary people as did the most exploitative capitalists.[34]

In 1932, Weil visited Germany to help Marxist activists who were at the time considered to be the strongest and best organised communists in Western Europe, but Weil considered them no match for the then up-and-coming fascists. When she returned to France, her political friends there dismissed her fears, thinking Germany would continue to be controlled by the centrists or by those to the left. After Hitler rose to power in 1933, Weil spent much of her time trying to help German communists fleeing his regime.[34] Weil would sometimes publish articles about social and economic issues, including "Oppression and Liberty," as well as numerous short articles for trade union journals. This work criticised popular Marxist thought and gave a pessimistic account of the limits of both capitalism and socialism. Leon Trotsky himself personally responded to several of her articles, attacking both her ideas and her as a person. However, according to Pétrement, he was influenced by some of Weil's thought.[35]

Weil participated in the French general strike of 1933, called to protest against unemployment and wage cuts. The following year, she took a 12-month leave of absence from her teaching position to work incognito as a labourer in two factories, one owned by Renault, believing that this experience would allow her to connect with the working class. In 1935, she resumed teaching and donated most of her income to political causes and charitable endeavours.

In 1936, despite her professed pacifism, she travelled to the Spanish Civil War to join the Republican faction. She identified as an anarchist,[36] and sought out the anti-fascist commander Julián Gorkin, asking to be sent on a mission as a covert agent to rescue the prisoner Joaquín Maurín. Gorkin refused, saying Weil would be sacrificing herself for nothing since it was highly unlikely that she could pass as a Spaniard. Weil replied that she had "every right"[37] to sacrifice herself if she chose, but after arguing for more than an hour, she was unable to convince Gorkin to give her the assignment. Instead she joined the anarchist Durruti Column of the French-speaking Sébastien Faure Century, which specialised in high-risk "commando"-style engagements.[38] As she was extremely short-sighted, Weil was a very poor shot, and her comrades tried to avoid taking her on missions, though she did sometimes insist. Her only direct participation in combat was to shoot with her rifle at a bomber during an air raid; in a second raid, she tried to operate the group's heavy machine gun, but her comrades prevented her, as they thought it would be best for someone less clumsy and near-sighted to use the weapon. After being with the group for a few weeks, she burnt herself over a cooking fire. She was forced to leave the unit, and was met by her parents who had followed her to Spain. They helped her leave the country, to recuperate in Assisi. About a month after her departure, Weil's unit was nearly wiped out at an engagement in Perdiguera in October 1936, with every woman in the group being killed.[39]

Weil was distressed by the Republican killings in eastern Spain, particularly when a fifteen-year-old Falangist was executed after he had been taken prisoner and Durruti had spent an hour trying to persuade him to change his political position before giving him until the next day to decide.[40]

During her stay in the Aragon front, Weil sent some chronicles to the French publication Le Libertaire, and on returning to Paris, she continued to write essays on labour, on management, war, and peace.[41]

Encounter with mysticism

Weil was born into a secular household and raised in "complete agnosticism".[43][44] As a teenager, she considered the existence of God for herself and decided nothing could be known either way. In her Spiritual Autobiography, however, Weil records that she always had a Christian outlook, taking to heart from her earliest childhood the idea of loving one's neighbour. Weil was attracted to the Christian faith beginning in 1935, when she had the first of three pivotal religious experiences: being moved by the beauty of villagers singing hymns in a procession she stumbled across while on holiday to Portugal (in Póvoa de Varzim).[45][46] Then, while in Assisi during the spring of 1937, Weil experienced a religious ecstasy in the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli—the same church in which Saint Francis of Assisi had prayed. She was led to pray for the first time in her life as Lawrence S. Cunningham relates:

Below the town is the beautiful church and convent of San Damiano where Saint Clare once lived. Near that spot is the place purported to be where Saint Francis composed the larger part of his "Canticle of Brother Sun". Below the town in the valley is the ugliest church in the entire environs: the massive baroque basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels, finished in the seventeenth century and rebuilt in the nineteenth century, which houses a rare treasure: a tiny Romanesque chapel that stood in the days of Saint Francis—the "Little Portion" where he would gather his brethren. It was in that tiny chapel that the great mystic Simone Weil first felt compelled to kneel down and pray.[47]

Weil had a third, more powerful, revelation a year later while reciting George Herbert's poem Love III, after which "Christ himself came down and took possession of me",[48] and, from 1938 on, her writings became more mystical and spiritual, while retaining their focus on social and political issues. She was attracted to Catholicism, but declined to be baptized at that time, preferring to remain outside due to "the love of those things that are outside Christianity".[49][50][51] During World War II, she lived for a time in Marseille, receiving spiritual direction from Joseph-Marie Perrin,[52] a Dominican Friar. Around this time, she met the French Catholic author Gustave Thibon, who later edited some of her work.

Weil did not limit her curiosity to Christianity. She was interested in other religious traditions—especially the Greek and Egyptian mysteries; Hinduism (especially the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita); and Mahayana Buddhism. She believed that all these and other traditions contained elements of genuine revelation,[53] writing:

Greece, Egypt, ancient India, the beauty of the world, the pure and authentic reflection of this beauty in art and science...these things have done as much as the visibly Christian ones to deliver me into Christ's hands as his captive. I think I might even say more.[54]

Nevertheless, Weil was opposed to religious syncretism, claiming that it effaced the particularity of the individual traditions:

Each religion is alone true, that is to say, that at the moment we are thinking of it we must bring as much attention to bear on it as if there were nothing else ... A "synthesis" of religion implies a lower quality of attention.[55]

Later years

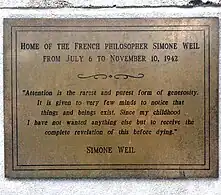

In 1942, Weil travelled to the United States with her family. She had been reluctant to leave France, but agreed to do so as she wanted to see her parents to safety and knew they would not leave without her. She was also encouraged by the fact that it would be relatively easy for her to reach Britain from the United States, where she could join the French Resistance. She had hopes of being sent back to France as a covert agent.[56]

Older biographies suggest Weil made no further progress in achieving her desire to return to France as an agent—she was limited to desk work in London, although this did give her time to write one of her largest and best known works: The Need for Roots.[57] Yet there is now evidence that Weil was recruited by the Special Operations Executive, with a view to sending her back to France as a clandestine wireless operator. In May 1943, preparations were underway to send her to Thame Park in Oxfordshire for training, but the plan was cancelled soon after, as her failing health became known.[58][59]

The rigorous work routine she assumed soon took a heavy toll. In 1943, Weil was diagnosed with tuberculosis and instructed to rest and eat well. However, she refused special treatment because of her long-standing political idealism and her detachment from material things. Instead, she limited her food intake to what she believed residents of German-occupied France ate. She most likely ate even less, as she refused food on most occasions. It is probable that she was baptized during this period.[60] Her condition quickly deteriorated, and she was moved to a sanatorium at Grosvenor Hall in Ashford, Kent.[23]

Death

After a lifetime of battling illness and frailty, Weil died in August 1943 from cardiac failure at the age of 34. The coroner's report said that "the deceased did kill and slay herself by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed".[61]

The exact cause of her death remains a subject of debate. Some claim that her refusal to eat came from her desire to express some form of solidarity toward the victims of the war. Others think that Weil's self-starvation occurred after her study of Arthur Schopenhauer.[62] In his chapters on Christian saintly asceticism and salvation, Schopenhauer had described self-starvation as a preferred method of self-denial. However, Simone Pétrement,[63] one of Weil's first and most significant biographers, regards the coroner's report as simply mistaken. Basing her opinion on letters written by the personnel of the sanatorium at which Simone Weil was treated, Pétrement affirms that Weil asked for food on different occasions while she was hospitalized and even ate a little bit a few days before her death; according to her, it was, in fact, Weil's poor health condition that eventually made her unable to eat.[64]

Weil's first English biographer, Richard Rees, offers several possible explanations for her death, citing her compassion for the suffering of her countrymen in occupied France and her love for and close imitation of Christ. Rees sums up by saying: "As for her death, whatever explanation one may give of it will amount in the end to saying that she died of love."[65]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Absence

Absence is the key image for her metaphysics, cosmology, cosmogony, and theodicy. She believed that God created by an act of self-delimitation—in other words, she argued that because God is conceived as utter fullness, a perfect being, no creature can exist except where God is not. Thus, creation occurred only when God withdrew in part. This idea mirrors tzimtzum, a central notion in the Jewish Kabbalah creation narrative.

This is, for Weil, an original kenosis ("emptiness") preceding the corrective kenosis of Christ's incarnation. Thus, according to her, humans are born in a damned position, not because of original sin, but because to be created at all they must be what God is not; in other words, they must be inherently "unholy" in some sense. This idea fits more broadly into apophatic theology.

This notion of creation is a cornerstone of her theodicy, for if creation is conceived this way—as necessarily entailing evil—then there is no problem of the entrance of evil into a perfect world. Nor does the presence of evil constitute a limitation of God's omnipotence under Weil's notion; according to her, evil is present not because God could not create a perfect world, but because the act of "creation" in its very essence implies the impossibility of perfection.

However, this explanation of the essentiality of evil does not imply that humans are simply, originally, and continually doomed; on the contrary, Weil claims that "evil is the form which God's mercy takes in this world".[66] Weil believed that evil, and its consequent affliction, serve the role of driving humans towards God, writing, "The extreme affliction which overtakes human beings does not create human misery, it merely reveals it."[67]

Affliction

Weil's concept of "affliction" (French: malheur) goes beyond simple suffering, though it certainly includes it. According to her, only some souls are capable of experiencing the full depth of affliction—the same souls that are also most able to experience spiritual joy. Weil's notion of affliction is a sort of suffering "plus" which transcends both body and mind, a physical and mental anguish that scourges the very soul.[68]

War and oppression were the most intense cases of affliction within her reach; to experience it, she turned to the life of a factory worker, while to understand it she turned to Homer's Iliad. (Her essay "The Iliad or the Poem of Force", first translated by Mary McCarthy, is a piece of Homeric literary criticism.) Affliction was associated both with necessity and with chance—it was fraught with necessity because it was hard-wired into existence itself, and thus imposed itself upon the sufferer with the full force of the inescapable, but it was also subject to chance inasmuch as chance, too, is an inescapable part of the nature of existence. The element of chance was essential to the unjust character of affliction; in other words, one's affliction should not usually—let alone always—follow from one's sin, as per traditional Christian theodicy, but should be visited upon one for no special reason.

The better we are able to conceive of the fullness of joy, the purer and more intense will be our suffering in affliction and our compassion for others. ...

Suffering and enjoyment as sources of knowledge. The serpent offered knowledge to Adam and Eve. The sirens offered knowledge to Ulysses. These stories teach that the soul is lost through seeking knowledge in pleasure. Why? Pleasure is perhaps innocent on condition that we do not seek knowledge in it. It is permissible to seek that only in suffering.

— Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace (chpt 16 'Affliction')

Metaxu: "Every separation is a link"

Metaxu, a concept Weil borrowed from Plato, is that which both separates and connects (e.g., as a wall separates two prisoners but can be used to tap messages). This idea of connecting distance was of the first importance for Weil's understanding of the created realm. The world as a whole, along with any of its components, including the physical body, is to be regarded as serving the same function for people in relation to God that a blind man's stick serves for him in relation to the world about him. They do not afford direct insight, but can be used experimentally to bring the mind into practical contact with reality. This metaphor allows any absence to be interpreted as a presence, and is a further component in Weil's theodicy.

Beauty

For Weil, "The beautiful is the experiential proof that the incarnation is possible". The beauty that is inherent in the form of the world (this inherency is proven, for her, in geometry, and expressed in all good art) is the proof that the world points to something beyond itself; it establishes the essentially telic character of all that exists. In Weil's concept, beauty extends throughout the universe:

"[W]e must have faith that the universe is beautiful on all levels...and that it has a fullness of beauty in relation to the bodily and psychic structure of each of the thinking beings that actually do exist and of all those that are possible. It is this very agreement of an infinity of perfect beauties that gives a transcendent character to the beauty of the world...He (Christ) is really present in the universal beauty. The love of this beauty proceeds from God dwelling in our souls and goes out to God present in the universe".[69]

She also wrote that "The beauty of this world is Christ's tender smile coming to us through matter".[69]

Beauty also served a soteriological function for Weil: "Beauty captivates the flesh in order to obtain permission to pass right to the soul." It constitutes, then, another way in which the divine reality behind the world invades people's lives: where affliction conquers with brute force, beauty sneaks in and topples the empire of the self from within.

Philosophy in Waiting for God

Attention

As Weil explains in her book Waiting for God, attention consists of suspending or emptying one's thought, such that one is ready to receive—to be penetrated by—the object to which one turns one's gaze, be that object one's neighbour, or ultimately, God.[70] As Weil explains, one can love God by praying to God, and attention is the very "substance of prayer": when one prays, one empties oneself, fixes one's whole gaze towards God, and becomes ready to receive God.[71] Similarly, for Weil, people can love their neighbours by emptying themselves, becoming ready to receive one's neighbour in all their naked truth, asking one's neighbour: "What are you going through?"[72]

Three Forms of the Implicit Love of God

In Waiting for God, Weil explains that the three forms of implicit love of God are (1) love of neighbour (2) love of the beauty of the world and (3) love of religious ceremonies.[73] As Weil writes, by loving these three objects (neighbour, world's beauty and religious ceremonies), one indirectly loves God before "God comes in person to take the hand of his future bride," since prior to God's arrival, one's soul cannot yet directly love God as the object.[74] Love of neighbour occurs (i) when the strong treat the weak as equals,[75] (ii) when people give personal attention to those that otherwise seem invisible, anonymous, or non-existent,[76] and (iii) when people look at and listen to the afflicted as they are, without explicitly thinking about God—i.e., Weil writes, when "God in us" loves the afflicted, rather than people loving them in God.[77] Second, Weil explains, love of the world's beauty occurs when humans imitate God's love for the cosmos: just as God creatively renounced his command over the world—letting it be ruled by human autonomy and matter's "blind necessity"—humans give up their imaginary command over the world, seeing the world no longer as if they were the world's center.[78] Finally, Weil explains, love of religious ceremonies occurs as an implicit love of God, when religious practices are pure.[79] Weil writes that purity in religion is seen when "faith and love do not fail," and most absolutely, in the Eucharist.[80]

Works

According to Lissa McCullough, Weil would likely have been "intensely displeased" by the attention paid to her life rather than her works. She believed it was her writings that embodied the best of her, not her actions and definitely not her personality. Weil had similar views about others, saying that if one looks at the lives of great figures in separation from their works, it "necessarily ends up revealing their pettiness above all", as it's in their works that they have put the best of themselves.[81]

Weil's most famous works were published posthumously.

In the decades since her death, her writings have been assembled, annotated, criticized, discussed, disputed, and praised. Along with some twenty volumes of her works, publishers have issued more than thirty biographies, including Simone Weil: A Modern Pilgrimage by Robert Coles, Harvard's Pulitzer-winning professor, who calls Weil 'a giant of reflection.'[82]

The Iliad, or The Poem of Force

Weil wrote The Iliad, or The Poem of Force (French: L'Iliade ou le poème de la force), a 24-page essay, in 1939.[83][84] First published in 1940 in Les Cahiers du Sud, the only significant literary magazine available in the French free zone.[84] As of 2007, it was still commonly used in university courses on the Classics.[85]

The essay focuses on the theme that Weil calls 'Force' in the Iliad, which she defines as "that x which turns anyone subjected to it into a thing."[86] In the opening sentences of the essay, she sets out her view of the role of Force in the poem:

The true hero, the true subject, the centre of the Iliad, is force. Force employed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man's flesh shrinks away. In this work, at all times, the human spirit is shown as modified by its relations with force, as swept away, blinded, by the very force it imagined it could handle, as deformed by the weight of the force it submits to.[86]: 5

The New York Review of Books has described the essay as one of Weil's most celebrated works,[84] while it has also been described as among "the twentieth century's most beloved, tortured, and profound responses to the world's greatest and most disturbing poem."[87]

Simone Petrement, a friend of Weil's, wrote that the essay portrayed the Iliad as an accurate and compassionate depiction of how both victors and victims are harmed by the use of force.[88]

The essay contains several extracts from the epic which Weil translated herself from the original Greek; Petrement records how Weil took over half an hour per line.[88]

The Need for Roots

Weil's book The Need for Roots was written in early 1943, immediately before her death later that year. She was in London working for the French Resistance and trying to convince its leader, Charles de Gaulle, to form a contingent of nurses who would serve at the front lines.

The Need for Roots has an ambitious plan. It sets out to address the past and to propose a road map for the future of France after World War II. She painstakingly analyzes the spiritual and ethical milieu that led to France's defeat by the German army, and then addresses these issues with the prospect of eventual French victory.

Gravity and Grace

While Gravity and Grace (French: La Pesanteur et la Grâce) is one of the books most associated with Simone Weil, the work was not intended to be a book at all. Rather, the work consists of various passages selected from Weil's notebooks and arranged topically by her friend Gustave Thibon. Weil had given Thibon some of her notebooks written before May 1942, but not with any intent to publish them. Hence, the resulting selections, organization and editing of Gravity and Grace were much influenced by Thibon, a devout Catholic (see Thibon's introduction to Gravity and Grace (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952) for more details).

Legacy

During her lifetime, Weil was known only in relatively narrow circles and even in France her essays were mostly read only by those interested in radical politics. During the first decade after her death, Weil rapidly became famous, attracting attention throughout the West. This was due to the publication of her work:

Around 1935, and especially after her first mystical experience in 1937, her writings took what many believed to be a new, religious direction. These writings, essays, notebooks, and letters she entrusted to the lay Catholic theologian Gustave Thibon in 1942, when, with her parents, she fled France. With the editorial help of Weil’s spiritual consultant (and sparring partner) Fr. Perrin, selections of these writings first made Weil widely known in the Anglo-American world."[89]

For the third quarter of the 20th century, she was widely regarded as the most influential person in the world on new work concerning religious and spiritual matters.[90] Her philosophical,[91] social and political thought also became popular, although not to the same degree as her religious work.[92]

Aside from influencing various fields of study, Weil deeply affected the personal lives of numerous individuals. Pope Paul VI said that Weil was one of his three greatest influences.[93]

Weil's popularity began to decline in the late 1960s and 1970s.[94] However, as more of her work was gradually published, many thousands of new secondary works by Weil scholars emerged. Some of these focused on achieving a deeper understanding of her religious, philosophical and political work. Others broadened the scope of Weil scholarship to investigate her applicability to fields like classical studies, cultural studies, education, and even technical fields like ergonomics.[46]

Praise

Many commentators have given highly positive assessments of Weil as a person, including T. S. Eliot, Dwight Macdonald, Leslie Fiedler, and Robert Coles. Some describe her as a saint, or even the greatest saint of the twentieth century.[95]

After they met at age 18, Simone de Beauvoir wroteː "I envied her for having a heart that could beat right across the world."[96]

Weil biographer Gabriella Fiori writes that Weil was "a moral genius in the orbit of ethics, a genius of immense revolutionary range."[97]

Maurice Schumann said that since her death there was "hardly a day when the thought of her life did not positively influence his own and serve as a moral guide."[96] In 1951, Albert Camus wrote that she was "the only great spirit of our times."[26] Foolish though she may have appeared at times—dropping a suitcase full of French resistance papers all over the sidewalk and scrambling to gather them up—her deep engagement with both the theory and practice of caritas, in all its myriad forms, functions as the unifying force of her life and thought.

Gustave Thibon, the French philosopher and Weil's close friend, recounts their last meeting, not long before her death: "I will only say that I had the impression of being in the presence of an absolutely transparent soul who was ready to be reabsorbed into original light."[98]

Criticism

Weil has been criticised, however, even by those who otherwise admired her deeply, such as T. S. Eliot, for being excessively prone to divide the world into good and evil, and for her sometimes intemperate judgments.

Weil was a harsh critic of the influence of Judaism on Western civilisation.[53] However, her niece Sylvie Weil and biographer Thomas R. Nevin argue that Weil did not reject Judaism and was heavily influenced by its precepts.[99]

Weil was an even harsher critic of the Roman Empire, in which she refused to see any value.[100]

On the other hand, according to Eliot, she held up the Cathars as exemplars of goodness, despite there being, in his view, little concrete evidence on which to base such an assessment.[53]

According to Pétrement she idolised Lawrence of Arabia, considering him to be a saint.[101]

A few critics have taken an overall negative view. Several Jewish writers, including Susan Sontag, have accused her of antisemitism, although this perspective is far from universal.[102]

A small minority of commentators have judged her to be psychologically unbalanced or sexually obsessed.[26] General Charles de Gaulle, her ultimate boss while she worked for the French Resistance, considered her "insane",[103] although even he was influenced by her and repeated some of her sayings for years after her death.[26][46]

Extensive Scholarly Coverage

A meta study from the University of Calgary found that between 1995 and 2012 over 2,500 new scholarly works had been published about her.[12]

Portrayal in film and onstage

"Approaching Simone" is a play created by Megan Terry. Dramatizing the life, philosophy and death of Simone Weil, Terry's play won the 1969/1970 Obie Award for Best Off-Broadway Play.

Weil was the subject of a 2010 documentary by Julia Haslett, An encounter with Simone Weil. Haslett noted that Weil had become "a little-known figure, practically forgotten in her native France, and rarely taught in universities or secondary schools".[104]

Weil was also the subject of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho's La Passion de Simone (2008), written with librettist Amin Maalouf. Of the piece, music critic Olivia Giovetti wrote:

"Framing her soprano soloist as Simone's imaginary sister (Literal? Metaphorical? Does it matter?), the narrative arc becomes a struggle to understand the dichotomy of Simone. Wrapped in this dramatic mystery, Saariaho's musical textures, haunting and moribund, create a meditative state. To go back to Bach's St. Matthew Passion, if that work, written for his time, serves to reinforce the (then-revolutionary) system of the Protestant church, then "La Passion de Simone," written for our time, questions the mystery of faith to reinforce the inexplicable experience of being human."[105]

Bibliography

Primary sources

Works in French

- Simone Weil, Œuvres complètes. (Paris : Gallimard, 1989–2006, 6 vols.)

- Réflexions sur la guerre (La Critique sociale, no. 10, November 1933)

- Chronicles from the Spanish Civil War, in: 'Le Libertaire', a French anarchist magazine, 1936

- La Pesanteur et la grâce (Paris : Plon, 1947)

- L'enracinement : Prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l'être humain (Gallimard [Espoir], 1949)

- Attente de Dieu (1950)

- La connaissance surnaturelle (Gallimard [Espoir], 1950)

- La Condition ouvrière (Gallimard [Espoir], 1951)

- Lettre à un religieux (Gallimard [Espoir], 1951)

- Les Intuitions pré-chrétiennes (Paris: Les Éditions de la Colombe, 1951)

- La Source grecque (Gallimard [Espoir], 1953)

- Oppression et Liberté (Gallimard [Espoir], 1955)

- Venise sauvée : Tragédie en trois actes (Gallimard, 1955)

- Écrits de Londres et dernières lettres (Gallimard [Espoir], 1957)

- Écrits historiques et politiques (Gallimard [Espoir], 1960)

- Pensées sans ordre concernant l'amour de Dieu (Gallimard [Espoir], 1962)

- Sur la science (Gallimard [Espoir], 1966)

- Poèmes, suivi de Venise sauvée (Gallimard [Espoir], 1968)

- Note sur la suppression générale des partis politiques (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1957 - Climats, 2006)

Works in English translation

- Awaiting God: A New Translation of Attente de Dieu and Lettre a un Religieux. Introduction by Sylvie Weil. Translation by Bradley Jersak. Fresh Wind Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1-927512-03-6.

- First and Last Notebooks: Supernatural Knowledge. Translated by Richard Rees. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2015.

- Formative Writings: 1929–1941. (1987). Dorothy Tuck McFarland & Wilhelmina Van Ness, eds. University of Massachusetts Press.

- The Iliad or the Poem of Force. Pendle Hill Pamphlet. Mary McCarthy trans.

- Intimations of Christianity among the Ancient Greeks. Translated by Elisabeth Chase Geissbuhler. New York: Routledge, 1998.

- Lectures on Philosophy. Translated by Hugh Price. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Letter to a Priest. Translated by Arthur Willis. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. Translated by Arthur Willis. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Gravity and Grace. Edited by Gustave Thibon. Translated by Arthur Willis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

- The Notebooks of Simone Weil. Routledge paperback, 1984. ISBN 0-7100-8522-2 [Routledge 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-32771-8]

- On Science, Necessity, & The Love of God. London: Oxford University Press, 1968. Richard Rees trans.

- On the Abolition of All Political Parties. Translated by Simon Leys. New York: The New York Review of Books, 2013.

- Oppression and Liberty. Edited by Albert Camus. Translated by Arthur Willis and John Petrie. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1973.

- Selected Essays, 1934–1943: Historical, Political and Moral Writings. Edited and translated by Richard Rees. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2015.

- Seventy Letters: Personal and Intellectual Windows on a Thinker. Translated by Richard Rees. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2015.

- Simone Weil's The Iliad or Poem of Force: A Critical Edition. James P. Holoka, ed. & trans. Peter Lang, 2005.

- Simone Weil: An Anthology. Sian Miles, editor. Virago Press, 1986.

- The Simone Weil Reader: A Legendary Spiritual Odyssey of Our Time. George A. Panichas, editor. David McKay Co., 1981.

- Two Moral Essays by Simone Weil—Draft for a Statement of Human Obligations & Human Personality. Ronald Hathaway, ed. Pendle Hill Pamphlet. Richard Rhees trans.

- Venice Saved. Translated by Silvia Panizza and Philip Wilson. New York: Bloomsbury, 2019.

- Waiting on God. Routledge Kegan Paul, 1951. Emma Craufurd trans.

- Waiting for God. Translated by Emma Craufurd. New York: HarperPerennial, 2009.

Online journal

- Attention a bi-monthly online journal (free) dedicated to exploring the life and legacy of Simone Weil.

Secondary sources

- Allen, Diogenes. (2006) Three Outsiders: Pascal, Kierkegaard, Simone Weil. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- Bell, Richard H. (1998) Simone Weil. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ———, editor. (1993) Simone Weil's Philosophy of Culture: Readings Toward a Divine Humanity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43263-4

- Bourgault, Sophie, & Daigle, Julie. (Eds.). (2020). Simone Weil, Beyond Ideology? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Castelli, Alberto, "The Peace Discourse in Europe 1900–1945, Routledge, 2019.

- Cha, Yoon Sook. (2017). Decreation and the Ethical Bind: Simone Weil and the Claim of the Other. Fordham University Press.

- Chenavier, Robert. (2012) Simone Weil: Attention to the Real, trans. Bernard E. Doering. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

- Davies, Grahame. (2007) Everything Must Change. Seren. ISBN 9781854114518

- Dietz, Mary. (1988). Between the Human and the Divine: The Political Thought of Simone Weil. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Doering, E. Jane. (2010) Simone Weil and the Specter of Self-Perpetuating Force. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Doering, E. Jane, and Eric O. Springsted, eds. (2004) The Christian Platonism of Simone Weil. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Esposito, Roberto. (2017). The Origin of the Political: Hannah Arendt or Simone Weil? (V. Binetti & G. Williams, Trans.). Fordham University Press.

- Finch, Henry Leroy. (1999) Simone Weil and the Intellect of Grace, ed. Martin Andic. Continuum International.

- Gabellieri, Emmanuel. (2003) Etre et don: L'unite et l'enjeu de la pensée de Simone Weil. Paris: Peeters.

- Goldschläger, Alain. (1982) Simone Weil et Spinoza: Essai d'interprétation. Québec: Naaman.

- Guilherme, Alexandre and Morgan, W. John, 2018, 'Simone Weil (1909-1943)-dialogue as an instrument of power', Chapter 7 in Philosophy, Dialogue, and Education: Nine modern European philosophers, Routledge, London and New York, pp. 109–126. ISBN 978-1-138-83149-0.

- Irwin, Alexander. (2002) Saints of the Impossible: Bataille, Weil, and the Politics of the Sacred. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McCullough, Lissa. (2014) The Religious Philosophy of Simone Weil. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1780767963

- Morgan, Vance G. (2005) Weaving the World: Simone Weil on Science, Mathematics, and Love. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-03486-9

- Morgan, W. John, 2019, Simone Weil's Lectures on Philosophy: A comment, RUDN Journal of Philosophy, 23 (4) 420–429. DOI: 10.22363/2313-2302-2019-23-4-420-429.

- Morgan, W. John, 2020, 'Simone Weil's 'Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God': A Comment', RUDN Journal of Philosophy, 24 (3), 398–409.DOI: 10.22363/2313-2302-2020-24-3-398-409.

- Moulakis, Athanasios (1998) Simone Weil and the Politics of Self-Denial, trans. Ruth Hein. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1162-0

- Panizza, Silvia Caprioglio. (2022). The Ethics of Attention: Engaging the Real with Iris Murdoch and Simone Weil. Routledge.

- Plant, Stephen. (2007) Simone Weil: A Brief Introduction, Orbis, ISBN 978-1-57075-753-2

- ———. (2007) The SPCK Introduction to Simone Weil, SPCK, ISBN 978-0-281-05938-6

- Radzins, Inese Astra (2006) Thinking Nothing: Simone Weil's Cosmology. ProQuest/UMI.

- Rhees, Rush. (2000) Discussions of Simone Weil. State University of New York Press.

- Rozelle-Stone, A. Rebecca. (Ed.). (2019). Simone Weil and Continental Philosophy. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Rozelle-Stone, A. Rebecca and Lucian Stone. (2013) Simone Weil and Theology. New York: Bloomsbury T & T Clark.

- ———, eds. (2009) Relevance of the Radical: Simone Weil 100 Years Later. New York: T & T Clark.

- Springsted, Eric O. (2010). Simone Weil and the Suffering of Love. Wipf & Stock.

- ———. (2021). Simone Weil for the Twenty-First Century. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Veto, Miklos. (1994) The Religious Metaphysics of Simone Weil, trans. Joan Dargan. State University of New York Press.

- von der Ruhr, Mario. (2006) Simone Weil: An Apprenticeship in Attention. London: Continuum.

- Winch, Peter. (1989) Simone Weil: "The Just Balance." Cambridge University Press.

- Winchell, James. (2000) 'Semantics of the Unspeakable: Six Sentences by Simone Weil,' in: "Trajectories of Mysticism in Theory and Literature", Philip Leonard, ed. London: Macmillan, 72–93. ISBN 0-333-72290-6

- Zaretsky, Robert. (2021). The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas. University of Chicago Press.

- ———. (2020) "The Logic of the Rebel: On Simone Weil and Albert Camus," Los Angeles Review of Books.

- ———. (2018) "What We Owe to Others: Simone Weil's Radical Reminder," New York Times.

Biographies

- Anderson, David. (1971). Simone Weil. SCM Press.

- Cabaud, Jacques. (1964). Simone Weil. Channel Press.

- Coles, Robert (1989) Simone Weil: A Modern Pilgrimage. Addison-Wesley. 2001 ed., Skylight Paths Publishing.

- Fiori, Gabriella (1989) Simone Weil: An Intellectual Biography. translated by Joseph R. Berrigan. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1102-2

- ———, (1991) Simone Weil. Una donna assoluta, La Tartaruga; Saggistica. ISBN 88-7738-075-6

- ———, (1993) Simone Weil. Une Femme Absolue Diffuseur-SODIS. ISBN 2-86645-148-1

- Gray, Francine Du Plessix (2001) Simone Weil. Viking Press.

- McLellan, David (1990) Utopian Pessimist: The Life and Thought of Simone Weil. New York: Poseidon Press.

- Nevin, Thomas R. (1991). Simone Weil: Portrait of a Self-Exiled Jew. Chapel Hill.

- Perrin, J.B. & Thibon, G. (1953). Simone Weil as We Knew Her. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Pétrement, Simone (1976) Simone Weil: A Life. New York: Schocken Books. 1988 edition.

- Plessix Gray, Francine du. (2001). Simone Weil. Penguin.

- Rexroth, Kenneth (1957) Simone Weil http://www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/essays/simone-weil.htm

- Guia Risari (2014) Il taccuino di Simone Weil, RueBallu 2014, Palermo, ISBN 978-88-95689-15-9

- Sogos Wiquel, Giorgia (2022) "Simone Weil. Private Überlegungen". Bonn, Free Pen Verlag. ISBN 978-3-945177-95-2.

- Terry, Megan (1973). Approaching Simone: A Play. The Feminist Press.

- White, George A., ed. (1981). Simone Weil: Interpretations of a Life. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Yourgrau, Palle. (2011) Simone Weil. Critical Lives series. London: Reaktion.

- Weil, Sylvie. (2010) At home with André and Simone Weil. Evanston: Northwestern.

- "Simone Weil: A Saint for Our Time?" magazine article by Jillian Becker; The New Criterion, Vol. 20, March 2002.

Audio recordings

- David Cayley, Enlightened by Love: The Thought of Simone Weil. CBC Audio (2002)

- "In Our Time" documentary on Weil, BBC Radio 4 (2015)[106]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ At the time, the ENS was part of the University of Paris according to the decree of 10 November 1903.

- ↑ « Avec Simone Weil et George Orwell », Le Comptoir

- ↑ George Andrew Panichas. (1999) Growing wings to overcome gravity. Mercer University Press. p. 63.

- ↑ Thomas R. Nevin. (1991) Simone Weil: Portrait of a Self-exiled Jew. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 198.

- ↑ Doering, E. Jane, and Eric O. Springsted, eds. (2004) The Christian Platonism of Simone Weil. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 29.

- ↑ "Course Catalogue - The Philosophy of Simone Weil (PHIL10161)". Drps.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ↑ Primary source: Simone Weil, First and Last Notebooks, Oxford University Press, 1970, pp. 211, 213 and 217. Commentary on the primary source: Richard H. Bell, Simone Weil's Philosophy of Culture: Readings Toward a Divine Humanity, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 27.

- ↑ Simone Weil, 2004, Gravity and Grace, London: Routledge. p. 32

- ↑ Dietz, Mary. (1988). Between the Human and the Divine: The Political Thought of Simone Weil. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 188.

- ↑ Athanasios Moulakis, Simone Weil and the Politics of Self-denial, University of Missouri Press, 1998, p. 141.

- ↑ "Dictionary.com | Meanings & Definitions of English Words". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- 1 2 Saundra Lipton and Debra Jensen (3 March 2012). "Simone Weil: Bibliography". University of Calgary. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- 1 2 Sheldrake, Philip (2007). A Brief History of Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 180–182. ISBN 978-1-4051-1770-8.

- ↑ Especially philosophy and theology—also political and social science, feminism, science, education, and classical studies.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Simone Weil", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Weil family", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ↑ Nevin, Thomas R. (1991). Simone Weil: Portrait of a Self-exiled Jew. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807819999.

- ↑ Pekonen, O. Chez les Weil. André and Simone by Sylvie Weil and At home with André and Simone Weil, translated from the French by Benjamin Ivry. Math Intelligencer *34, *76–78 (2012)

- ↑ "The Weil Conjectures by Karen Olsson review – maths and mysticism". The Guardian. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); pp. 4-7.

- ↑ According to Fogelman, Cole and others, various studies have found that a common formative experience for marked altruists is to suffer a hurtful loss and then to receive strong support from loving carers.

- ↑ Eva Fogelman (23 March 2012). "Friday Film: Simone Weil's Mission of Empathy". The Jewish Daily Forward. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- 1 2 Robert Coles (2001). Simone Weil: A Modern Pilgrimage (Skylight Lives). SkyLight Paths. ISBN 978-1893361348.

- ↑ According to Pétrement (1988), p. 14, family friends would refer to Simone and André as "the genius and the beauty".

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); pp. 4–7, 194

- 1 2 3 4 John Hellman (1983). Simone Weil: An Introduction to Her Thought. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-0-88920-121-7.

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); pp. 27–29

- ↑ Hellman, John (1982). Simone Weil: An Introduction to her Thought. Wilrid Laurier University Press.

- 1 2 Liukkonen, Petri. "Simone Weil". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 24 April 2007.

- ↑ Alain, "Journal" (unpublished). Cited in Petrement, Weil, 1:6.

- ↑ Simone Weil: Complete Works I "Premieres Écrits Philosophiques". Gallimard. 1988. p. 161.

- ↑ André Chervel. "Les agrégés de l'enseignement secondaire. Répertoire 1809-1950". Laboratoire de recherche historique Rhône-Alpes. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); pp. 189–191

- 1 2 Simone Pétrement (1988); p. 176

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); p. 178

- ↑ McLellan, David (1990). Utopian Pessimist: The Life and Thought of Simone Weil. Poseidon Press. ISBN 9780671685218. p121

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); p. 271

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); p. 272

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); p. 278

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); pp. 280–330

- ↑ S. Weil, Spiritual Autobiography

- ↑ S. Weil, What is a Jew, cited by Panichas.

- ↑ George A Panichas (1977). Simone Weil Reader. Moyer Bell. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-918825-01-8.

- ↑ George A Panichas (1977). Simone Weil Reader. Moyer Bell. pp. xxxviii. ISBN 978-0-918825-01-8.

- 1 2 3 Simone Weil (2005). Sian Miles (ed.). An Anthology. Penguin Book. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-14-118819-5.

- ↑ Cunningham, Lawrence S. (2004). Francis of Assisi: performing the Gospel life. Illustrated edition. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-2762-4, ISBN 978-0-8028-2762-3. Source: (accessed: September 15, 2010), p. 118

- ↑ cited by Panichas and other Weil scholars,

- ↑ S. Weil, Spiritual Autobiography, cited by Panichas and Plant.

- ↑ George A Panichas (1977). Simone Weil Reader. Moyer Bell. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-918825-01-8.

- ↑ Stephen Plant (1997). Great Christian Thinkers: Simone Weil. Liguori Publications. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-0764801167.

- ↑ Weil Simone (1966). Attente de Dieu. Fayard.

- 1 2 3 Simone Weil (2002). The Need for Roots. Routledge. p. xi, preface by T. S. Eliot. ISBN 978-0-415-27102-8.

- ↑ Letter to Father Perrin, 26 May 1942

- ↑ Notebooks of Simone Weil, volume 1

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); chpt. 15 'Marseilles II', see esp. pp. 462-463.

- ↑ This was originally a lengthy report on options for regenerating France after an allied victory, though it was later published as a book.

- ↑ "Simone Weil" by Nigel Perrin. Archived 2012-12-10 at archive.today

- ↑ Simone Weil Personal File, ref. HS 9/1570/1, National Archives, Kew

- ↑ Eric O. Springsted, "The Baptism of Simone Weil" in Spirit, Nature and Community: Issues in the Thought of Simone Weil (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994) - https://sunypress.edu/Books/S/Spirit-Nature-and-Community.

- ↑ McLellan, David (1990). Utopian Pessimist: The Life and Thought of Simone Weil. Poseidon Press. ISBN 9780671685218., Inquest verdict quoted on p. 266.

- ↑ McLellan, David (1990). Utopian Pessimist: The Life and Thought of Simone Weil. Poseidon Press., p. 30

- ↑ Pétrement, Simone (1988). Simone Weil: A life. Schocken, 592 pp.

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988); chpt. 17 'London', see esp. pp. 530-539.

- ↑ Richard Rees (1966). Simone Weil: A Sketch for a Portrait. Oxford University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-19-211163-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gravity and Grace, Metaxu, page 132

- ↑ Weil, Simone. Gravity and Grace. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952.

- ↑ This notion of Weil's bears a strong resemblance to the Asian notion of han, which has received attention in recent Korean theology, for instance in the work of Andrew Park. Like "affliction", han is more destructive to the whole person than ordinary suffering.

- 1 2 Weil, Simone. Waiting For God. Harper Torchbooks, 1973, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 111–112. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 105. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 137–199. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 137. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 149. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 150–151. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 158–160. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 181. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Weil, Simone (1973). Waiting for God (1st Harper colophon ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 187. ISBN 0-06-090295-7. OCLC 620927.

- ↑ Lissa McCullough (2014). The Religious Philosophy of Simone Weil: An Introduction. I.B. Tauris. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1780767963.

- ↑ Alonzo L. McDonald, from the forward Wrestling with God, An Introduction to Simone Weil by The Trinity Forum c. 2008

- ↑ "War and the Iliad". The New York Review of books. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 Weil, Simone (2005). An Anthology. Penguin Books. pp. 182, 215. ISBN 0-14-118819-7.

- ↑ Meaney, Marie (2007). Simone Weil's Apologetic Use of Literature: Her Christological Interpretation of Ancient Greek Texts. Clarendon Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-921245-3.

- 1 2 Weil, Simone (1965). Translated by Mary McCarthy. "The Iliad, or The Poem of Force" (PDF). Chicago Review. 18 (2): 5–30. doi:10.2307/25294008. JSTOR 25294008. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ↑ "Books in Brief". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- 1 2 Petrement, Simone (1988) [1976]. Simone Weil: A Life. Translated by Rosenthal, Raymond (English ed.). Random House. pp. 361–363. ISBN 0805208623.

- ↑ Tony Lynch. "Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". p. Section 2. Writings. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Even some of her critics conceded this, see Hellman (1982), p. 4-5

- ↑ Note, however, that while Weil's philosophical work received much popular attention, including by intellectuals, she was relatively little studied by professional philosophers, especially in the English-speaking world, despite philosophy being the subject in which she was professionally trained. See, for example, the Introduction of Simone Weil: "The Just Balance" by Peter Winch, which is an excellent source for a philosophical discussion of her ideas, especially for those interested in the overlap between her work and that of Wittgenstein.

- ↑ Various scholars have listed her among the top five French political writers of the first half of the twentieth century, see Hellman (1982), p. 4-5.

- ↑ The other two being Pascal and Georges Bernanos; see Hellman (1982), p. 1

- ↑ Not only do we need a citation, we also need an explanation.

- ↑ See Hellman (1982) for a list the biographers who have portrayed her as a saint.

- 1 2 Weil H. Bell (1998). The Way of Justice as Compassion. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxii. ISBN 0-8476-9080-6.

- ↑ "The Lonely Pilgrimage of Simone Weil - The Washington Post | HighBeam Research". 16 May 2011. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ↑ Erica DaCosta (June 2004). "The Four Simone Weils" (PDF). Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Ivry, Benjamin (30 March 2009). "Simone Weil's Rediscovered Jewish Inspiration". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- ↑ She even disliked Romans who are normally admired by progressives, such as Virgil, Marcus Aurelius, and Tacitus, reserving moderate praise only for the Gracchi.

- ↑ Simone Pétrement (1988), p. 329, 334

- ↑ Several of her most ardent admirers have also been Jewish, Wladimir Rabi, a contemporary French intellectual for example, called her the greatest French spiritual writer of the first half the twentieth century. See Hellman (1982), p. 2

- ↑ "Elle est folle". See Malcolm Muggeridge, "The Infernal Grove", Fontana: Glasgow (pbk), 1975, p. 210.

- ↑ Doris Toumarkine (23 March 2012). "Film Review: An Encounter with Simone Weil". Film Journal International. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ "Deep Listen: Kaija Saariaho • VAN Magazine". VAN Magazine. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ "BBC Radio 4 - In Our Time, Simone Weil". BBC. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

Further reading

- Brădăţan, Costică (January 2023). "Christ at the assembly line : how a year of factory work transformed Simone Weil". Commonweal. 150 (1): 32–39.[lower-alpha 1]

- Weil, Simone (1952). "Part II: Uprootedness". The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties towards Mankind. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 40–180. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

———————

- Notes

- ↑ Excerpted from the author's In praise of failure.

External links

- Lynch, Tony. "Simone Weil". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- A. Rebecca Rozelle-Stone; Benjamin P. Davis (2018). "Simone Weil". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Weil family", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- American Weil Society and 2009 Colloquy—Website for 2009 Colloquy at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

- Simone Weil on Labor — hosted at the Center for Global Justice

- simoneweil.net — biographical notes, photos & bilingual quotes that illustrate key concepts, including force, necessity, attention and "le malheur"

- Works by Simone Weil — public domain in Canada

- An Encounter with Simone Weil — Documentary on Weil by Julia Haslett, premiered in Amsterdam in November 2010

- Radio broadcast on Weil as part of BBC's In our Time series (2012)

- Simone Weil's texts (Catalan translation)

- Philosophical Investigations, Special Issue on Simone Weil (1909–1943), January–April 2020.