A gun is a device designed to propel a projectile using pressure or explosive force.[1][2] The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid (e.g. in water guns/cannons), or gas (e.g. light-gas gun). Solid projectiles may be free-flying (as with bullets and artillery shells) or tethered (as with Tasers, spearguns and harpoon guns). A large-caliber gun is also called a cannon.

The means of projectile propulsion vary according to designs, but are traditionally effected pneumatically by a high gas pressure contained within a barrel tube (gun barrel), produced either through the rapid exothermic combustion of propellants (as with firearms), or by mechanical compression (as with air guns). The high-pressure gas is introduced behind the projectile, pushing and accelerating it down the length of the tube, imparting sufficient launch velocity to sustain its further travel towards the target once the propelling gas ceases acting upon it after it exits the muzzle. Alternatively, new-concept linear motor weapons may employ an electromagnetic field to achieve acceleration, in which case the barrel may be substituted by guide rails (as in railguns) or wrapped with magnetic coils (as in coilguns).

The first devices identified as guns or proto-guns appeared in China from around AD 1000.[3] By the end of the 13th century, they had become "true guns," metal barrel firearms that fired single projectiles which occluded the barrel.[4][5] Gunpowder and gun technology spread throughout Eurasia during the 14th century.[6][7][8]

Etymology and terminology

The origin of the English word gun is considered to derive from the name given to a particular historical weapon. Domina Gunilda was the name given to a remarkably large ballista, a mechanical bolt throwing weapon of enormous size, mounted at Windsor Castle during the 14th century. This name in turn may have derived from the Old Norse woman's proper name Gunnhildr which combines two Norse words referring to battle.[9] "Gunnildr", which means "War-sword", was often shortened to "Gunna".[10]

The earliest recorded use of the term "gonne" was in a Latin document circa 1339. Other names for guns during this era were "schioppi" (Italian translation-"thunderers"), and "donrebusse" (Dutch translation-"thunder gun") which was incorporated into the English language as "blunderbuss".[10] Artillerymen were often referred to as "gonners" and "artillers"[11] "Hand gun" was first used in 1373 in reference to the handle of guns.[12]

Definition

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a gun could mean "a piece of ordnance usually with high muzzle velocity and comparatively flat trajectory," " a portable firearm," or "a device that throws a projectile."[13]

Gunpowder and firearm historian Kenneth Chase defines "firearms" and "guns" in his Firearms: A Global History to 1700 as "gunpowder weapons that use the explosive force of the gunpowder to propel a projectile from a tube: cannons, muskets, and pistols are typical examples."[14]

True gun

According to Tonio Andrade, a historian of gunpowder technology, a "true gun" is defined as a firearm which shoots a bullet that fits the barrel as opposed to one which does not, such as the shrapnel shooting fire lance.[3] As such, the fire lance, which appeared between the 10th and 12th centuries AD, as well as other early metal barrel gunpowder weapons have been described as "proto-guns"[15] Joseph Needham defined a type of firearm known as the "eruptor," which he described as a cross between a fire lance and a gun, as a "proto-gun" for the same reason.[16] He defined a fully developed firearm, a "true gun," as possessing three basic features: a metal barrel, gunpowder with high nitrate content, and a projectile that occluded the barrel.[4] The "true gun" appears to have emerged in late 1200s China, around 300 years after the appearance of the fire lance.[4][5] Although the term "gun" postdates the invention of firearms, historians have applied it to the earliest firearms such as the Heilongjiang hand cannon of 1288[17] or the vase shaped European cannon of 1326.[18]

Classic gun

Historians consider firearms to have reached the form of a "classic gun" in the 1480s, which persisted until the mid-18th century. This "classic" form displayed longer, lighter, more efficient, and more accurate design compared to its predecessors only 30 years prior. However this "classic" design changed very little for almost 300 years and cannons of the 1480s show little difference and surprising similarity with cannons later in the 1750s. This 300-year period during which the classic gun dominated gives it its moniker.[19] The "classic gun" has also been described as the "modern ordnance synthesis."[20]

History

Proto-gun

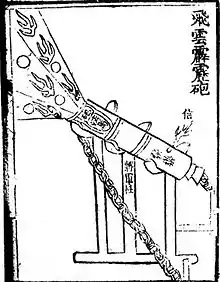

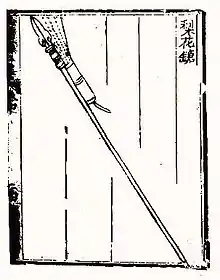

Gunpowder was invented in China during the 9th century.[21][22][23] The first firearm was the fire lance, which appeared in China between the 10–12th centuries.[24][25][26] It was depicted in a silk painting dated to the mid-10th century, but textual evidence of its use does not appear until 1132, describing the siege of De'an.[24] It consisted of a bamboo tube of gunpowder tied to a spear or other polearm. By the late 1100s, ingredients such as pieces of shrapnel like porcelain shards or small iron pellets were added to the tube so that they would be blown out with the gunpowder.[27] It was relatively short ranged and had a range of roughly 3 meters by the early 13th century.[28] This fire lance is considered by some historians to be a "proto-gun" because its projectiles did not occlude the barrel.[15] There was also another "proto-gun" called the eruptor, according to Joseph Needham, which did not have a lance but still did not shoot projectiles which occluded the barrel.[16]

Transition to true guns

In due course, the proportion of saltpeter in the propellant was increased to maximise its explosive power.[29] To better withstand that explosive power, the paper and bamboo of which fire-lance barrels were originally made came to be replaced by metal.[23] And to take full advantage of that power, the shrapnel came to be replaced by projectiles whose size and shape filled the barrel more closely.[29] Fire lance barrels made of metal appeared by 1276.[30] Earlier in 1259 a pellet wad that filled the barrel was recorded to have been used as a fire lance projectile, making it the first recorded bullet in history.[27] With this, the three basic features of a gun were put in place: a barrel made of metal, high-nitrate gunpowder, and a projectile which totally occludes the muzzle so that the powder charge exerts its full potential in propellant effect.[31] The metal barrel fire lances began to be used without the lance and became guns by the late 13th century.[27]

Guns such as the hand cannon were being used in the Yuan dynasty by the 1280s.[32] Surviving cannons such as the Heilongjiang hand cannon and the Xanadu Gun have been found dating to the late 13th century and possibly earlier in the early 13th century.[33]

In 1287, the Yuan dynasty deployed Jurchen troops with hand cannons to put down a rebellion by the Mongol prince Nayan.[32] The History of Yuan records that the cannons of Li Ting's soldiers "caused great damage" and created "such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other."[34] The hand cannons were used again in the beginning of 1288. Li Ting's "gun-soldiers" or chongzu (銃卒) carried the hand cannons "on their backs". The passage on the 1288 battle is also the first to use the name chong (銃) with the metal radical jin (金) for metal-barrel firearms. Chong was used instead of the earlier and more ambiguous term huo tong (fire tube; 火筒), which may refer to the tubes of fire lances, proto-cannons, or signal flares.[35] Hand cannons may have been used in the Mongol invasions of Japan. Japanese descriptions of the invasions mention iron and bamboo pao causing "light and fire" and emitting 2–3,000 iron bullets.[36] The Nihon Kokujokushi, written around 1300, mentions huo tong (fire tubes) at the Battle of Tsushima in 1274 and the second coastal assault led by Holdon in 1281. The Hachiman Gudoukun of 1360 mentions iron pao "which caused a flash of light and a loud noise when fired."[37] The Taiheki of 1370 mentions "iron pao shaped like a bell."[37]

Spread

The exact nature of the spread of firearms and its route is uncertain. One theory is that gunpowder and cannons arrived in Europe via the Silk Road through the Middle East.[38][39] Hasan al-Rammah had already written about fire lances in the 13th century, so proto-guns were known in the Middle East at that point.[40] Another theory is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century.[38][39]

The earliest depiction of a cannon in Europe dates to 1326 and evidence of firearm production can be found in the following year.[8] The first recorded use of gunpowder weapons in Europe was in 1331 when two mounted German knights attacked Cividale del Friuli with gunpowder weapons of some sort.[41][42] By 1338 hand cannons were in widespread use in France.[43] English Privy Wardrobe accounts list "ribaldis", a type of cannon, in the 1340s, and siege guns were used by the English at Calais in 1346.[44] Early guns and the men who used them were often associated with the devil and the gunner's craft was considered a black art, a point reinforced by the smell of sulfur on battlefields created from the firing of guns along with the muzzle blast and accompanying flash.[45]

Around the late 14th century in Europe, smaller and portable hand-held cannons were developed, creating in effect the first smooth-bore personal firearm. In the late 15th century the Ottoman empire used firearms as part of its regular infantry. In the Middle East, the Arabs seem to have used the hand cannon to some degree during the 14th century.[14] Cannons are attested to in India starting from 1366.[46]

The Joseon kingdom in Korea learned how to produce gunpowder from China by 1372[6] and started producing cannons by 1377.[47] In Southeast Asia, Đại Việt soldiers used hand cannons at the very latest by 1390 when they employed them in killing Champa king Che Bong Nga.[48] Chinese observer recorded the Javanese use of hand cannon for marriage ceremony in 1413 during Zheng He's voyage.[49][50] Hand guns were utilized effectively during the Hussite Wars.[51] Japan knew of gunpowder due to the Mongol invasions during the 13th century, but did not acquire a cannon until a monk took one back to Japan from China in 1510,[52] and guns were not produced until 1543, when the Portuguese introduced matchlocks which were known as tanegashima to the Japanese.[53]

Gunpowder technology entered Java in the Mongol invasion of Java (1293 A.D.).[54]: 1–2 [55][56]: 220 Majapahit under Mahapatih (prime minister) Gajah Mada utilized gunpowder technology obtained from the Yuan dynasty for use in the naval fleet.[57]: 57 During the following years, the Majapahit army have begun producing cannons known as cetbang. Early cetbang (also called Eastern-style cetbang) resembled Chinese cannons and hand cannons. Eastern-style cetbangs were mostly made of bronze and were front-loaded cannons. It fires arrow-like projectiles, but round bullets and co-viative projectiles[58] can also be used. These arrows can be solid-tipped without explosives, or with explosives and incendiary materials placed behind the tip. Near the rear, there is a combustion chamber or room, which refers to the bulging part near the rear of the gun, where the gunpowder is placed. The cetbang is mounted on a fixed mount, or as a hand cannon mounted on the end of a pole. There is a tube-like section on the back of the cannon. In the hand cannon-type cetbang, this tube is used as a socket for a pole.[59]: 94

Arquebus and musket

The arquebus was a firearm that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the early 15th century.[60] Its name is derived from the German word Hackenbüchse. It originally described a hand cannon with a lug or hook on the underside for stabilizing the weapon, usually on defensive fortifications.[61] In the early 1500s, heavier variants known as "muskets" that were fired from resting Y-shaped supports appeared. The musket was able to penetrate heavy armor, and as a result armor declined, which also made the heavy musket obsolete. Although there is relatively little to no difference in design between arquebus and musket except in size and strength, it was the term musket which remained in use up into the 1800s.[62] It may not be completely inaccurate to suggest that the musket was in its fabrication simply a larger arquebus. At least on one occasion the musket and arquebus have been used interchangeably to refer to the same weapon,[63] and even referred to as an "arquebus musket."[64] A Habsburg commander in the mid-1560s once referred to muskets as "double arquebuses."[65]

A shoulder stock[66] was added to the arquebus around 1470 and the matchlock mechanism sometime before 1475. The matchlock arquebus was the first firearm equipped with a trigger mechanism[12][67] and the first portable shoulder-arms firearm.[68] Before the matchlock, handheld firearms were fired from the chest, tucked under one arm, while the other arm maneuvered a hot pricker to the touch hole to ignite the gunpowder.[69]

The Ottomans may have used arquebuses as early as the first half of the 15th century during the Ottoman–Hungarian wars of 1443–1444.[70] The arquebus was used in substantial numbers during the reign of king Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (r. 1458–1490).[71] Arquebuses were used by 1472 by the Spanish and Portuguese at Zamora. Likewise, the Castilians used arquebuses as well in 1476.[72] Later, a larger arquebus known as a musket was used for breaching heavy armor, but this declined along with heavy armor. Matchlock firearms continued to be called musket.[73] They were used throughout Asia by the mid-1500s.[74][75][76][77]

Transition to classic guns

Guns reached their "classic" form in the 1480s. The "classic gun" is so called because of the long duration of its design, which was longer, lighter, more efficient, and more accurate compared to its predecessors 30 years prior. The design persisted for nearly 300 years and cannons of the 1480s show little variation from as well as surprising similarity with cannons three centuries later in the 1750s. This 300-year period during which the classic gun dominated gives it its moniker.[19]

The classic gun differed from older generations of firearms through an assortment of improvements. Their longer length-to-bore ratio imparted more energy into the shot, enabling the projectile to shoot further. They were also lighter since the barrel walls were thinner, allowing faster dissipation of heat. They no longer needed the help of a wooden plug to load since they offered a tighter fit between projectile and barrel, further increasing the accuracy of firearms[79] – and were deadlier due to developments such as gunpowder corning and iron shot.[80]

Modern guns

Several developments in the 19th century led to the development of modern guns.

In 1815, Joshua Shaw invented percussion caps, which replaced the flintlock trigger system. The new percussion caps allowed guns to shoot reliably in any weather condition.[81]

In 1835, Casimir Lefaucheux invented the first practical breech loading firearm with a cartridge. The new cartridge contained a conical bullet, a cardboard powder tube, and a copper base that incorporated a primer pellet.[82]

Rifles

While rifled guns did exist prior to the 19th century in the form of grooves cut into the interior of a barrel, these were considered specialist weapons and limited in number.[73]

The rate of fire of handheld guns began to increase drastically. In 1836, Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse invented the Dreyse needle gun, a breech-loading rifle which increased the rate of fire to six times that of muzzle loading weapons.[82] In 1854, Volcanic Repeating Arms produced a rifle with a self-contained cartridge.[83]

In 1849, Claude-Étienne Minié invented the Minié ball, the first projectile that could easily slide down a rifled barrel, which made rifles a viable military firearm, ending the smoothbore musket era.[84] Rifles were deployed during the Crimean War with resounding success and proved vastly superior to smoothbore muskets.[84]

In 1860, Benjamin Tyler Henry created the Henry rifle, the first reliable repeating rifle.[85] An improved version of the Henry rifle was developed by Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1873, known as the Model 1873 Winchester rifle.[85]

Smokeless powder was invented in 1880 and began replacing gunpowder, which came to be known as black powder.[86] By the start of the 20th century, smokeless powder was adopted throughout the world and black powder, what was previously known as gunpowder, was relegated to hobbyist usage.[87]

Machine guns

In 1861, Richard Jordan Gatling invented the Gatling gun, the first successful machine gun, capable of firing 200 gunpowder cartridges in a minute. It was fielded by the Union forces during the American Civil War in the 1860s.[88] In 1884, Hiram Maxim invented the Maxim gun, the first single-barreled machine gun.[88]

The world's first submachine gun (a fully automatic firearm which fires pistol cartridges) able to be maneuvered by a single soldier is the MP 18.1, invented by Theodor Bergmann. It was introduced into service in 1918 by the German Army during World War I as the primary weapon of the Stosstruppen (assault groups specialized in trench combat).

In civilian use, the captive bolt pistol is used in agriculture to humanely stun farm animals for slaughter.[89]

The first assault rifle was introduced during World War II by the Germans, known as the StG44. It was the first firearm to bridge the gap between long range rifles, machine guns, and short range submachine guns. Since the mid-20th century, guns that fire beams of energy rather than solid projectiles have been developed, and also guns that can be fired by means other than the use of gunpowder.

Operating principle

Most guns use compressed gas confined by the barrel to propel the bullet up to high speed, though devices operating in other ways are sometimes called guns. In firearms the high-pressure gas is generated by combustion, usually of gunpowder. This principle is similar to that of internal combustion engines, except that the bullet leaves the barrel, while the piston transfers its motion to other parts and returns down the cylinder. As in an internal combustion engine, the combustion propagates by deflagration rather than by detonation, and the optimal gunpowder, like the optimal motor fuel, is resistant to detonation. This is because much of the energy generated in detonation is in the form of a shock wave, which can propagate from the gas to the solid structure and heat or damage the structure, rather than staying as heat to propel the piston or bullet. The shock wave at such high temperature and pressure is much faster than that of any bullet, and would leave the gun as sound either through the barrel or the bullet itself rather than contributing to the bullet's velocity.[90][91]

Components

Barrel

Barrel types include rifled—a series of spiraled grooves or angles within the barrel—when the projectile requires an induced spin to stabilize it, and smoothbore when the projectile is stabilized by other means or rifling is undesired or unnecessary. Typically, interior barrel diameter and the associated projectile size is a means to identify gun variations. Bore diameter is reported in several ways. The more conventional measure is reporting the interior diameter (bore) of the barrel in decimal fractions of the inch or in millimetres. Some guns—such as shotguns—report the weapon's gauge (which is the number of shot pellets having the same diameter as the bore produced from one English pound (454g) of lead) or—as in some British ordnance—the weight of the weapon's usual projectile.

Projectile

A gun projectile may be a simple, single-piece item like a bullet, a casing containing a payload like a shotshell or explosive shell, or complex projectile like a sub-caliber projectile and sabot. The propellant may be air, an explosive solid, or an explosive liquid. Some variations like the Gyrojet and certain other types combine the projectile and propellant into a single item.

Types

Military

Handguns

Hunting

Machine guns

Autocannon

Artillery

Tank

Rescue equipment

Training and entertainment

Directed-energy weapons

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Chambers Dictionary, Allied Chambers – 199, page 717

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary - gun

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Needham 1986, p. 10.

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, p. 104.

- 1 2 Needham 1986, p. 307.

- ↑ Nicolle 1983, p. 18.

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, p. 75.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster, Inc. (1990). The Merriam-Webster's New Book of Word Histories. Basic Books. pg.207

- 1 2 Kelly 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 30.

- 1 2 Phillips 2016.

- ↑ "Definition of GUN". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 13 August 2023.

- 1 2 Chase 2003, p. 1.

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, p. 37.

- 1 2 Needham 1986, p. 9.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ McLachlan 2010, p. 8.

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 106.

- ↑ Buchanan 2006, p. 2 "With its ninth century AD origins in China, the knowledge of gunpowder emerged from the search by alchemists for the secrets of life, to filter through the channels of Middle Eastern culture, and take root in Europe with consequences that form the context of the studies in this volume."

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 7 "Without doubt it was in the previous century, around +850, that the early alchemical experiments on the constituents of gunpowder, with its self-contained oxygen, reached their climax in the appearance of the mixture itself."

- 1 2 Chase 2003, pp. 31–32

- 1 2 Needham 1986, p. 222.

- ↑ Chase 2003, p. 31.

- ↑ Lorge 2008, p. 33-34.

- 1 2 3 Andrade 2016, p. 52.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 46.

- 1 2 Crosby 2002, p. 99.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 228.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 10

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, p. 53.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 294.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 304.

- ↑ Purton 2010, p. 109.

- 1 2 Needham 1986, p. 295.

- 1 2 Norris 2003:11

- 1 2 Chase 2003:58

- ↑ Chase 2003, p. 84.

- ↑ DeVries, Kelly (1998). "Gunpowder Weaponry and the Rise of the Early Modern State". War in History. 5 (2): 130. doi:10.1177/096834459800500201. JSTOR 26004330. S2CID 56194773.

- ↑ von Kármán, Theodore (1942). "The Role of Fluid Mechanics in Modern Warfare". Proceedings of the Second Hydraulics Conference: 15–29.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 77.

- ↑ David Nicolle, Crécy 1346: Triumph of the longbow, Osprey Publishing; June 25, 2000; ISBN 978-1-85532-966-9.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 32.

- ↑ Khan 2004, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Chase 2003, p. .

- ↑ Tran 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ Mayers (1876). "Chinese explorations of the Indian Ocean during the fifteenth century". The China Review. IV: p. 178.

- ↑ Manguin 1976, p. 245.

- ↑ "First use of hand guns in war". Guinness World Records. 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 430.

- ↑ Lidin 2002, pp. 1–14.

- ↑ Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". T'oung Pao. 3: 1–11.

- ↑ Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) Vol. 2. Paris: Editions de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. Page 178.

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Pramono, Djoko (2005). Budaya Bahari. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9789792213768.

- ↑ A type of scatter bullet — when shot it spews fire, splinters and bullets, and can also be arrows. The characteristic of this projectile is that the bullet does not cover the entire bore of the barrel. Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9 and 220.

- ↑ Averoes, Muhammad (2020). Antara Cerita dan Sejarah: Meriam Cetbang Majapahit. Jurnal Sejarah, 3(2), 89 - 100.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 443.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 426.

- ↑ Chase 2003, p. 61.

- ↑ Adle 2003, p. 475.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 165.

- ↑ Chase 2003, p. 92.

- ↑ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1991). "The Nature of Handguns in Mughal India: 16th and 17th Centuries". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 52: 378–389. JSTOR 44142632.

- ↑ Petzal 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ Partington 1999, p. xxvii.

- ↑ Arnold 2001, p. 75.

- ↑ Ágoston, Gábor (2014). "Firearms and Military Adaptation: The Ottomans and the European Military Revolution, 1450–1800". Journal of World History. 25 (1): 85–124. doi:10.1353/jwh.2014.0005. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 143042353.

- ↑ Bak 1982, pp. 125–40.

- ↑ Partington 1999, p. 123.

- 1 2 Arnold 2001, p. 75-78.

- ↑ Khan 2004, p. 131.

- ↑ Tran 2006, p. 107.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 169.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 171.

- ↑ "Pair of Miquelet Pistols". Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, pp. 104–106.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 107.

- ↑ Willbanks 2004, p. 11.

- 1 2 Willbanks 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Willbanks 2004, p. 14.

- 1 2 Willbanks 2004, p. 12.

- 1 2 Willbanks 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 294.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 232.

- 1 2 Chase 2003, p. 202.

- ↑ "Captive Bolt Stunning Equipment and the Law – How it applies to you". Archived from the original on 2014-04-05.

- ↑ Dunlap, Roy F. (June 1963). Gunsmithing. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0770-1.

- ↑ "How Guns Work". Pew Pew Tactical. 2 April 2021.

References

- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60391-1

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas F. (2001), History of Warfare: The Renaissance at War, London: Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-0-304-35270-8

- Bak, J. M. (1982), Hunyadi to Rákóczi: War and Society in Late Medieval and Early Modern Hungary

- Benton, Captain James G. (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2nd ed.). West Point, New York: Thomas Publications. ISBN 978-1-57747-079-3.

- Breverton, Terry (2012), Breverton's Encyclopedia of Inventions

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-1878-7.

- Buchanan, Brenda J. (2006), "Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History", Technology and Culture, Aldershot: Ashgate, 49 (3): 785–86, doi:10.1353/tech.0.0051, ISBN 978-0-7546-5259-5, S2CID 111173101

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-718-5

- Cook, Haruko Taya (2000), Japan at War: An Oral History, Phoenix Press

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel.

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79158-8.

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen.

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 978-0-904040-13-5.

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43519-2

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing.

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on 25 March 2004.

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650–1830, UCL Press Limited

- Smee, Harry (2020), Gunpowder and Glory

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013), Cathayan Arrows and Meteors: The Origins of Chinese Rocketry

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 23 July 2007.

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-03718-6.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–45.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd..

- Lee, R. Geoffrey (1981). Introduction to Battlefield Weapons Systems and Technology. Oxford: Brassey's Defence Publishers. ISBN 0080270433.

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 978-981-05-5380-7

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 978-8791114120

- Lorge, Peter (2005), Warfare in China to 1600, Routledge

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29 (3): 594–605, doi:10.2307/3105275, JSTOR 3105275, S2CID 112733319

- Lu, Yongxiang (2015), A History of Chinese Science and Technology 2

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- May, Timothy (2012), The Mongol Conquests in World History, Reaktion Books

- McLachlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press.

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China, Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1976), Science and Civilization in China, Volume 5 Part 3, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Part 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08573-1

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Part 7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nicolle, David (1983), Armies of the Ottoman Turks 1300-1774

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, vol. 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Padmanabhan, Thanu (2019), The Dawn of Science: Glimpses from History for the Curious Mind, Bibcode:2019dsgh.book.....P

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press.

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen.

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2011), The Seal of the Unity of the Three

- Purton, Peter (2009), A History of the Early Medieval Siege c. 450–1200, The Boydell Press

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-449-6

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Romane, Julian (2020), The First & Second Italian Wars 1494-1504

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000–1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea AD 612–1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-478-8

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial (2006), ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1

- Wilkinson, Philip (9 September 1997), Castles, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7894-2047-3

- Wilkinson-Latham, Robert (1975), Napoleon's Artillery, France: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85045-247-1

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- Williams, Anthony G. (2000), Rapid Fire, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., ISBN 978-1-84037-435-3

- Kouichiro, Hamada (2012), 日本人はこうして戦争をしてきた

- Tatsusaburo, Hayashiya (2005), 日本の歴史12 - 天下一統