The Halqa is a Moroccan concept that refers to people's theatre, an audience circle in the middle of which is the Helayqi (the artist who presents the show). This term has always been associated with the Moroccan intangible cultural richness of music, dance, singing, and storytelling.[1]

This form of gathering slipped during history and moved into the Moroccan popular culture, and formed its special character, to become an intangible cultural heritage. For Moroccan society, the Halqa is a practice rooted in Moroccan culture that is linked and cohesive to a geographical location. From this came the anthropological interest in this tradition associated with the place or the "place of memory," as Pierre Nora called it.

Etymology

The term Halqa (plural Helaki) means in arabic a circle and it refers to the distribution formed by spectators or listeners (circular shape) around a person or group of persons who give a speech or present a show. Hence, this word can be used on anything that takes a circular or semi-circular shape. In the Arab world, it is known that the lessons that were held in schools (Medersa) used to take a circular shape in the past, while students sat in a semi-circle around their teacher. This form of gathering was prominent as well in the ancient Greek society in the so-called Agora.[2]

History

_el_Fna-Tschadseeflug_1930-31-LBS_MH02-08-0448.tiff.jpg.webp)

Some historical writings indicate that the art of the Halqa in Morocco originated in the 19th century AD in the city of Marrakech in the Jemaa el-Fna square, before it spread to the rest of the cities. Especially in its weekly markets Souq, which were visited by people from different areas surrounding the city.[3]

The presentation of the Halqa is supervised by specialists in the art of storytelling, mime and acrobatic games, as they present their performances in the markets and squares of major cities such as Bab al-Saqma, Bab al-Futuh, Bab 'Ajisah in Fez, or al-Hedim square, Bab Mansour al-'Alaj in Meknes, and Jemaa el-Fna Square in Marrakech[4] to create a mixture of comedy, drama, poetry, singing, dance and storytelling, sometimes even the audience participates in it, and often personifies amazigh and Arab myths and legends inspired by the diverse Moroccan culture.[5]

As for the Besaat, i.e. jokes or tease, it was at first just a traditional imitations to entertain the sultans and statesmen on the one hand, and to amuse the people on the other hand, such as characterizing the story of the Balarj on the ringtones of the bendir and the melodies of the flute.[6]

The first concerts of the Besaat theater were presented in Morocco in front of Sultan Muhammad bin Abdullah[4] and were used for preaching and guidance in an entertaining way. This art developed from this short show over the years and thanks to the encouragement of the sultans.[6]

These Halayqiya artists came to Rabat on the occasion of Ashura, so they went to the royal palace in an atmosphere of humor and fun amidst the curiosity of adults and children,[6] and when they reach the royal palace, they began to perform their shows.[4]

If each group has its own characteristics that distinguish it, the people of Fez have specialized in imitation. It is said that the themes of the sketches they presented became social and patriotic in addition to their comedic character.[6] These sketches dealt with social issues presented in an amusing form in front of the king who is aware of the hidden dramas of their owners, so he researches these issues and empowers the owners of their rights.[4]

In 2003, UNESCO considered the Jemaa el-Fna square as a cultural space and a form of cultural expression, and a masterpiece of oral tradition. Out of 32 files, 19 were selected, including the Jemaa el-Fna square file, as a place that shines in various types of intangible heritage.[5]

This art has known periods of ups and downs, and has begun to gradually disappear in certain Moroccan cities. In addition to a few spaces, the Jemaa el-Fna square in Marrakech, which has been labeled by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage 2008, is still the vital cradle that embraces the pioneers of Halqa art with wonderful stories of local oral heritage or acrobatic movements performed by young men who never entered a sports institute, but inherited a gestural heritage traditional which is specific to certain tribes.[7]

The traditional storytelling

Definition

The traditional storytelling is defined as a narrative heritage that is part of Moroccan folk oral literature. It is transmitted from generation to generation orally, and is usually presented in the form of a story, a riddle or a fable, the purpose of which is to draw a lesson at the end. It is one of the most important means of transmitting culture and moral values to future generations.[8]

Traditional storytelling in the Marrakesh community

The traditional storytelling is part of the identity of the Marrakchi community. The art of storytelling circulated among people, in a family form, before the Halqa of the storyteller of Jemaa El-Fna square became one of the most important constituent elements of the activities of this square. As a result, storytelling has become an important part of intangible heritage.[9]

Mohammed Bariz

Muhammad Bariz was born in 1959 in Marrakech. He was influenced by his mother's tales and by the most famous storyteller of his time, Moulay Muhammad al-Jabri. He entered the realm of storytelling through its wide doors in 1969, mastering the art of storytelling, and the method of maintaining balance of the Ḥalqa through his storytelling and oral theatrical embodiment. His repertoire has remained filled to this day with the precious things he never ceases to tell. Over three decades, his storytelling legacy has endured, and he and others like him have preserved it in Jemaa El-Fna Square and passed it on to generations who now carry the torch of its enhancement and preservation.[10]

Moroccan woman and the traditionnal storytelling

Women have always been a source of inspiration for storytellers, their presence adding to the intrigue and suspense of storytelling. Not only she was one of its heroines of the tale, but she was the narrator of its events. As a result, women have had two fundamental roles in the transmission of oral tales throughout history: sometimes as a character helping to influence the course of events, and sometimes as the narrator of the tale herself.[11]

Women's leadership in conveying the traditional tales within Moroccan society

In a former era, women used to hold gatherings for storytelling in a closed, warm family atmosphere, as part of traditional rituals that are now on the verge of extinction, in which they celebrate the art of the storytelling with the company of the whole family.[11]

The storytelling gathering usually consisted of women and children, and every woman pours into it the stories she has in her chest. The woman narrator was that bridge through which the child crosses in his imagination the events of the story, to settle into slumber, and then sleep in stillness. Just like the lullabies that are sought for the infant before he surrenders to sleep.[11]

She was, and still, playing the role of the socialization of the child, starting from the lullabies of the cradle, to the riddles and stories of childhood, which inculcate in them the values of goodness and the principles of identity. The narrator transports them to the depth of imagination, so that she and her listeners have a collective imagination that is an outlet and a refuge to escape from the realistic void.[11]

Oral narration is a function that grandmothers and mothers took care of in the past. However, the common collective arena is not devoid of the presence of female storytellers and women narrators who practiced the art of storytelling by entering the Halqa, whether in the Jemaa El Fna square, or in the hospitality of the largest Riads of Marrakech , so they were artists, carrying the torch of this heritage, especially here as an example: the honorable storyteller called Lalla Ruqia, was about 111 years from now, she lived in the suite reserved for women at the Zaouia of Sidi Bel Abbes, where all the unmarried, poor, honorable women were gathered.[11]

Jmi'a and Zahra too learned the art of storytelling as children from an old slave-lady in the Makhzen House, who was the storyteller of Sultan Mawla al-Hasan at the time. Sultan Hassan I, back then (18th century AD), was also instructed to hold special evenings for tales in the Agdal Palace in Marrakesh, under the supervision of the best storytellers of the city of Marrakech.[8]

The honorable Lalla Ruqia, Lalla Jmi’a, and Lalla Zahra, and if they are preserved in the Moroccan collective memory, they are no exception. It is certain that there are female storytellers other than them, who were inadvertently or perhaps deliberately omitted from the Moroccan Marrakeshi documentation record, and we did not receive anything from their news.[8]

Popular theater

_(15722800436).jpg.webp)

The popular theater played an important role in the Halqa performances, it is built on the capabilities of the artist by resurrecting the oral heritage from its old forms by his ability to imitate and improvise that was one of the most important qualities that captivated minds. The Halqa is related to the symbol, and as it is an expression of the past, it is able to touch the nostalgia for the heritage of the ancestors.[12][13] There are so many types of popular theater: Rma, Rehhala, Mejdoub, Baqsheesh, Lamsiyeh, owners of pigeons, snakes, monkeys and donkeys, “knowers” of the secrets of the horoscope, astrologers, magicians and singers ... Each of these has its own way of playing the theatre, but they are all based on employing elements of popular memory.[14]

In this art, the theatrical game takes place in front of everyone, everyone watches from his angle, and everyone is shown in front of everyone.[14]

Within the circle of Ḥalqa is a special time, a time cut out from the real time. It is a time of enjoyment and collective retrieval of memory, of origin, of the village, the desert, and the distant ravine.[14]

Halqa of comedy

It consists of an individual or a group of two to three people performing a short scene (sketches) that satirizes certain aspects of daily, political or cultural life. Some of them use magic tricks to attract and entertain the spectators, and the great comedians in the second half of the twentieth century were distinguished by a high reputation, such as: Baqsheesh, Flifla, moul lahmar, Saroukh, and the quotes of Lamsiyyeh in the twenty-first century. Each generation has its own way, and each has its own comic and expressive style in conveying the jokes and short scenes that it has inherited, inspired by the customs and traditions of Moroccan society.[5]

Halqa of acrobatics show

These shows are presented by young people from Sous and their tutor Sidi Hamad or Musa. They wear red and green suits. From an early age, acrobats are forced to live by very strict rules of life. They learn from the elderly to flex the muscles of their bodies and subject them to difficult exercises as their embodiment of a pyramid made up of all the members of the group. The secret of the success of the type of Halqa is the teamwork that allows such physical performance.[5]

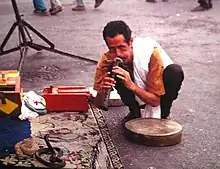

Halqa of animal tamers

The Halqa of animal tamers, of the monkey trainers for example, delight audiences because of the animals' innate abilities to mimic people's facial expressions. Also these of the snake tamers, who have a very special aura around them, always arousing in the spectators respect mixed with fear. They have been immunized since birth against snake venom, and they also have the ability to absorb the deadly poison directly, which enables them, at the same time, to save human lives. This is a grant and a gift, which they owe to their sheikh, Sidi Ahmed Ben Aissa, whose zawiya is located in the city of Meknes.[5]

During the Haḍra ceremonies, which are organized each year on the day of the Prophet's birthday, the Issawi show the diversity of their dignities. But instead Jemaa el-Fna, they content themselves with submitting the snakes to their laws, uniting with them in enchantment to the sound of ghaita music. However, behind the desire to entertain passers-by on the ring, Issawi always remains deeply respectful of his snakes.[5]

.jpg.webp)

Halqa of traditional music

Traditional music is one of the components of the Halqa that energizes the Jemaa El-Fna square theater. Al-Malhoun, Gnaoua, Al-Ruwais, Al-Ghaita, Awlad Hmar, Hadawa, Al-Aita Al-Houzia (Al-Hawzi), Hamadcha, Awlad Sidi Rahal, all of them are independent musical variations that represent the diverse musical heritage of Morocco.[15]

Traditional music consists of poems called Zajal, inspired by popular literature, sung in the Moroccan dialectal Arabic, in the form of musical and lyrical sequences, accompanied by playing an instrument: the Cambri, the flute, the violin, Taarija or Tara (tambourine), to distinguish the rhythm. In this way, a lyrical and musical show is formed, inspired by the lifestyle of passers-by, or derived from the traditions and stories of one of the various regions of Morocco.[15] It may also be an improvisation from the inspiration of the moment that gives the Halqa a character of pleasure and familiarity.[9]

Valorization of the art of Halqa as Moroccan popular oral heritage in our time

The presence of Helayqi is nothing but fairness to his ancestors of the Helayqi, an appreciation and continuity in the preservation of this oral heritage. Indeed, Halqa art in general and Helayqi artists in particular have always formed the core of a form of spontaneous theatrical expression of social issues such as heritages, customs, traditions and the politics of model and laws of life in society. Since then, they have been seen as the faithful guardians, recruits and defenders of an oral culture that is hundreds of years old.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Ahmed Skounti - Ouidad tebbaa (2006). La Place Jemaa El Fna patrimoine immateriel de Marrakech du Maroc et de lhumanite 2006 (in French). Bureau de l’UNESCO pour le Maghreb.

- ↑ Ladenburger, Thomas (2015). AL HALQA, Les derniers conteurs. Germany: Thomas Ladenburger Filmproduktion.

- ↑ Net, Aljazeera. "فن الحلقة بالمغرب.. تراث شفوي مهدد بالأفول". Aljazeera Net (in Arabic).

- 1 2 3 4 Manīʻī, Ḥasan; منيعي، حسن. (2000). Abḥāth fī al-masraḥ al-Maghribī (al-Ṭabʻah 2., muṣaḥḥaḥah wa-munaqqaḥah ed.). al-Dār al-Bayḍāʼ: Manshūrāt al-Zaman. ISBN 9981-1733-5-5. OCLC 62117637.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ahmed Skounti - Ouidad tebbaa (2006). La Place Jemaa El Fna patrimoine immateriel de Marrakech du Maroc et de lhumanite 2006 (in French). Bureau de l’UNESCO pour le Maghreb.

- 1 2 3 4 شقرون, عبد الله (1974). "لمحات من تاريخ المسرح المغربي". مجلة الفنون.

- ↑ Aljazeera. "فن الحلقة بالمغرب تراث يفقد جمهوره". Aljazeera Net.

- 1 2 3 Légey, Doctoresse (2010). Contes & legendes populaires du Maroc. Editions du Sirocco. ISBN 978-9954-8851-0-9. OCLC 1026162717.

- 1 2 3 Ladenburger, Thomas (2015). AL HALQA, Les derniers conteurs. Germany: Thomas Ladenburger Filmproduktion.

- ↑ الشرق, الأوسط. "محمد باريز.. أشهر الحكواتيين المغاربة". الشرق الأوسط.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rachele, Borghi (2017). Le rôle de la femme marocaine sur la Place Jama' al Fna. Hal Open Science.

- ↑ Malḥūnī, ʻAbd al-Raḥmān; ملحوني، عبد الرحمن. (2015). Dhākirat Marrākush : ṣuwar min tārīkh wa-adabīyāt al-ḥalqah bi-sāḥat Jāmiʻ al-Fanāʼ : muqārabah lil-thaqāfah al-shaʻbīyah (al-Ṭabʻah al-thānīyah ed.). Marrākush. ISBN 978-9954-35-965-5. OCLC 970659535.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Rahali, Mohammed. "المسرح الشعبي المغربي الإرهاصات والتأسيس: الحلقة والأشكال ما قبل المسرحية". الحوار المتمدن.

- 1 2 3 Hespress. "فن الحلقة: المسرح والذاكرة الشعبية". Hespress.

- 1 2 Aydoun, Ahmed (2014). Musique du Maroc, seconde édition revue et augmentée (in French) (Seconde édition revue et augmentée ed.). Maroc: Editions La Croisée des Chemins. p. 224. ISBN 9789954104927.