39°34′17″N 75°35′01″W / 39.57139°N 75.58361°W

| Harbor Defenses of the Delaware | |

|---|---|

Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island | |

| Active | 1896–1950[1] |

| Country | |

| Branch | United States Army Coast Artillery Corps |

| Type | Coast artillery |

| Role | Harbor Defense Command |

| Part of |

|

| Garrison/HQ |

|

| Mascot(s) | Oozlefinch |

The Harbor Defenses of the Delaware was a United States Army Coast Artillery Corps harbor defense command.[1] It coordinated the coast defenses of the Delaware River estuary from 1897 to 1950, beginning with the Endicott program. These included both coast artillery forts and underwater minefields. The areas protected included the cities of Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington along with the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal. The command originated circa 1896 as an Artillery District and became the Coast Defenses of the Delaware in 1913, with defenses initially at and near Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island near Delaware City. In 1925 the command was renamed as a Harbor Defense Command. During World War II the defenses were relocated to Fort Miles on Cape Henlopen at the mouth of the Delaware Bay.[2][3][4][5]

History

Early forts on the Delaware River

Colonial period

.jpg.webp)

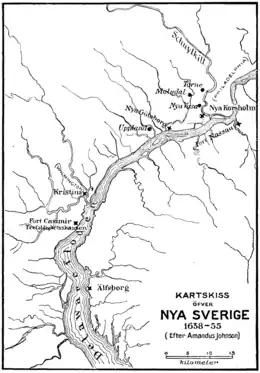

Europeans came to the Delaware Valley in the early 17th century, with the first settlements founded by the Dutch, who in 1623 built Fort Nassau on the Delaware River (which they called the South River, or Zuyd Rivier in Dutch) opposite its confluence with the Schuylkill River in what is now Brooklawn, New Jersey. Fort Nassau was a factorij or fortified trading post. The Dutch considered the entire Delaware River valley to be part of their New Netherland colony, which extended from what is now southern Delaware to Rhode Island. In 1638, Swedish, Finnish, and renegade Dutch settlers led by Peter Minuit established the colony of New Sweden at Fort Christina (present-day Wilmington, Delaware) and quickly spread out in the valley. In 1644, New Sweden supported the Susquehannocks in their military defeat of the English colony of Maryland. In 1648, the Dutch built Fort Beversreede on the west bank of the Delaware, south of the Schuylkill near the present-day Eastwick neighborhood, to reassert their dominion over the area. The Swedes responded by building Fort Nya Korsholm, or New Korsholm, after a town in Finland with a Swedish majority. In 1655, a Dutch military campaign led by New Netherland Director-General Peter Stuyvesant took control of the Swedish colony, ending its claim to independence. The Swedish and Finnish settlers continued to have their own militia, religion, and courts, and to enjoy substantial autonomy under the Dutch. The English conquered the New Netherland colony in 1664, though the situation did not change substantially until 1682 when the area was included in William Penn's charter for Pennsylvania, under which the city of Philadelphia was founded. Penn's colony originally included both Pennsylvania and Delaware; by 1704 the latter split off as the colony of Lower Delaware, though the two shared a common governor.[6]

William Penn and many of the Pennsylvania colonists were Quakers, members of a pacifist Christian sect. They fostered good relations with Lenape (Delaware) tribe, purchasing the colony's land from them, and had the only significant European settlements in the Americas without fortifications. In the 1740s French and Spanish privateers entered the Delaware River, threatening the city. During King George's War (1744–1748), Benjamin Franklin raised a militia called the Association for General Defense, because the legislators of the city decided to take no action to defend Philadelphia "either by erecting fortifications or building Ships of War". He raised money to create earthwork defenses and buy artillery. The largest of these was the "Association Battery" or "Grand Battery" of 50 guns, on the site that became Joshua Humphreys' shipyard in 1794 and is now the Coast Guard Station Philadelphia.[7] At the end of the war, commanders disbanded the militia and left derelict the defenses of the city. With the outbreak of the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years' War) in the 1750s, plans were drawn up for a fort on Mud Island (later called Fort Mifflin) in the Delaware at the southern end of today's city limits, but no fort was built.[8] Eventually, in 1771 British General Thomas Gage assigned Captain John Montresor of the British Corps of Engineers to the task of designing and building a fort on the island. Montresor submitted six designs to Penn and the Board of Commissioners, estimating £40,000 for an adequate fort with 40 guns and a 400-man garrison. His designs were all considered too expensive by the Board, which provided only £15,000 for purchasing the island and building the fort. Construction began in 1771, but in mid-1772 Montresor left the project and returned to New York.[9] Work on the fort ended a year later, with only the east and south walls built.[10]

Revolutionary War

.tif.jpg.webp)

In April 1775 the American Revolution broke out full-scale at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. These battles were followed shortly by the convening of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia on May 11, 1775. The Philadelphia Committee of Safety, headed by Benjamin Franklin, decided to protect the city by obstructing British access to the Delaware River. Three forts were built to protect two lines of chevaux de frise obstacles in the river, designed by Robert Smith. One line was at Fort Billingsport, New Jersey, and another was between Fort Mifflin (called "Fort on Mud Island" or the "Fort Island Battery" at the time) and Fort Mercer.[11] A third line of obstacles was downstream at Marcus Hook with no forts nearby.[12] Forts Mercer and Billingsport in New Jersey were designed by Tadeusz Kościuszko and built as earthworks; work also resumed on Fort Mifflin and all three forts were garrisoned during 1777.[13] Meanwhile, the Continental Congress relocated to Baltimore in early 1776 due to a threat of British attack, later returning to Philadelphia and issuing the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, attracting further British attention to the city.

In early 1777 the British planned to cut New England off from the rest of the colonies by sending a force under John Burgoyne southward from Montreal through the Lake Champlain area and the Hudson Valley to Albany. This was intended to be supported by a force under General William Howe advancing northward from New York City. However, George Germain, a British civilian official managing the war in London, also gave approval for Howe to capture Philadelphia.[14] Howe proceeded with the Philadelphia plan and largely failed to support Burgoyne's campaign. The Philadelphia campaign was time-consuming but successful; the British took a lengthy water route through Chesapeake Bay, then marched overland to defeat Washington at the Battle of Brandywine southwest of Philadelphia on September 11, and entered the city unopposed on September 26. The Continental Congress left the city ahead of the British occupation, moving first to Lancaster and then to York, Pennsylvania.[15]

Howe had the luxury of bypassing most of Philadelphia's defenses, occupying the city following his victory at Brandywine. However, his primary supply route was the Delaware River, with the forts and lines of chevaux de frise blocking it. They cut through the line near Marcus Hook without opposition, and easily took Fort Billingsport and its line of obstacles on October 2. They then laid siege to Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer, unsuccessfully attacking the latter by land and river in the Battle of Red Bank on October 22. The 1,200 Hessians of the assault force suffered over 350 casualties, the British also losing HMS Augusta (64 guns) and HMS Merlin (18 guns) to grounding.[16][17] The latter was possibly an indirect result of engagement by the Continental and Pennsylvania navies, which also provided enfilading fire against the Hessians.[18] The siege was commanded by John Montresor, designer of Fort Mifflin. On November 10 bombardment of the fort began in earnest. The fort was evacuated and burned (to impede its use by the British) five days later, with the Patriot forces of over 400 men suffering about 250 casualties.[19] Fort Mifflin was "entirely beat down; every piece of cannon entirely dismounted", as reported by George Washington.[20] On November 18, Fort Mercer was evacuated in the face of a British force of 2,000, their artillery having breached the fort's walls.[11]

Burgoyne's campaign came to a defeat in the Battles of Saratoga, leading to his eventual surrender on October 17.[21] This victory persuaded France to enter the war on the Patriot side. Word of it reached Commissioner Benjamin Franklin in Paris on December 4, and negotiations resulted in France declaring war on Britain in March 1778.[22]

Washington and his army encamped at Valley Forge in December 1777, about 20 miles (32 km) from Philadelphia, where they stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. However, the army eventually emerged from Valley Forge in good order.[23]

Meanwhile, there was a shakeup in the British command. General Howe resigned his position, and was replaced by Lieutenant General Henry Clinton as commander-in-chief. France's entry into the war forced a change in British war strategy, and Clinton was ordered by the government to abandon Philadelphia and defend New York City, now vulnerable to French naval power. Clinton shipped many Loyalists and most of his heavy equipment by sea to New York, and evacuated Philadelphia on June 18, 1778. Washington's army shadowed Clinton's, and Washington successfully forced a battle at Monmouth Courthouse on June 28, the last major battle in the North. Washington's second-in-command, General Charles Lee, who led the advance force of the army, ordered a controversial retreat early in the battle, allowing Clinton's army to regroup. By July, Clinton was in New York City, and Washington was again at White Plains, New York. Both armies were back where they had been two years earlier.

The military focus of the war shifted to the southern colonies. Eventually, the American victory in the Yorktown campaign on October 19, 1781 proved to be the key to independence; the British received word of it on November 25. This precipitated a collapse of Lord North's Tory government in March 1782. The new Whig government suspended offensive operations in the Thirteen Colonies and commenced lengthy peace negotiations, culminating in the Treaty of Paris that ended the war on September 3, 1783.[24]

1783–War of 1812

The ruins of Fort Mifflin lay derelict until 1793, when rebuilding began under what was later called the first system of US coastal fortifications. Pierre L'Enfant, also responsible for planning Washington, D.C., supervised the reconstruction and designed the rebuild in 1794.[10] Reconstruction work began on the fort in 1795 under the auspices of engineer officer Louis de Tousard, who from 1795 to 1800 worked on coastal defenses between Massachusetts and the Carolinas.[25] The initial goal was to rebuild the fort to accommodate 48 guns.[26] The army officially named the fort after Thomas Mifflin, a Continental Army officer and the first post-independence Governor of Pennsylvania, in 1795.[27] Rebuilding the fort consumed $94,000 of a total fort budget of $278,000 in 1798 and 1799 alone (in 1799 money).[28] Also, the U.S. Congress met in Philadelphia until 1800 and Fort Mifflin was well garrisoned until then, usually with two companies.[29]

During the War of 1812 efforts were made to fortify Pea Patch Island, later the site of Fort Delaware. This was the first of three times new defenses were built further seaward along the Delaware as gun ranges increased; the river estuary widens rapidly downstream of the island and at the time rendered smoothbore cannon defenses ineffective. This plan of defense was largely coordinated by Capt. Samuel Babcock, who was working nearby on similar defenses in Philadelphia. During this time a seawall and dykes were built around the island. There is no known evidence that any progress was made on the actual fortification by war's end. The original plan was to build a Martello tower on the island.[30] Other sources state that an earthwork fort was built on the island during the war and demolished in 1821; also, a wooden fort existed from 1814 to 1824.[31][32] Battery Park in Delaware City is on the site of the Delaware City Battery, an earthwork erected in 1814.[33]

1815–1860

In 1815 the first Fort Delaware was designed by Joseph G. Totten and construction soon began on Pea Patch Island. This fort was in the shape of a five-pointed star, with large bastions and short curtain walls. The five-pointed star design is viewed as "transitional" between the second and third systems of US fortifications.[34] Capt. Samuel Babcock supervised the work from about August 1819 until August 20, 1824.[35] Completion of the project was delayed years past the proposed date due to uneven settling, improper pile placement and the island's marshy nature. In one occurrence an entire section of 43,000 bricks had to be taken down, cleaned, and reworked due to massive cracking. In 1822, Colonel Totten and General Simon Bernard were on the island to inspect the faulty works. Captain Babcock was severely criticized for altering Totten's plans without orders. Babcock subsequently appeared before a court-martial for his actions in late 1824. It was determined he was not guilty of neglect but rather error in judgement and he was acquitted.[35]

On February 7, 1821, the Board of Engineers reported: "In the Delaware, the fort on the Pea Patch island, and one on the Delaware shore opposite, defend the water passage as far below Philadelphia as localities will permit: They force an enemy to land forty miles below the city to attack it by land, and thus afford time for the arrival of succors [...] The two projected forts will also have the advantages of covering the canal destined to connect the Chesapeake with the Delaware[.]"[36] The fort on the Delaware shore may refer to the Delaware City Battery; a permanent battery was not built there until the Civil War.

The star fort was garrisoned prior to 1825. In 1831 it was wrecked by a fire. Captain Richard Delafield was tasked with designing and building a replacement; the first fort was demolished in 1833. The new fort was intended, in Capt. Delafield's words, "as a huge bastioned polygonal form to be built in masonry."[30] Delafield desired his fort to be "a marvel of military architecture on Pea Patch", and the design was much larger than the star fort.[34] Construction began on the foundations in 1836, but was interrupted by a legal challenge over whether the island historically lay in Delaware or New Jersey, thus disputing Delaware's right to convey the island to the federal government. The case dragged on for over ten years. In 1848 an arbitrator ruled in Delaware's favor.[37] It appears no further work was done on this fort.[34]

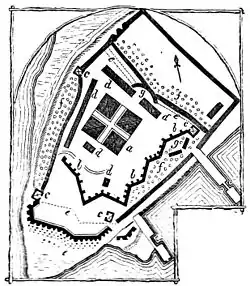

The present Fort Delaware was erected mainly between 1848 and 1860 as one of the larger forts of the third system of US fortifications. Although major construction was wrapped up before the Civil War broke out in 1861, the post engineer did not declare the fort finished until 1868.[38] The fort was designed by Army chief engineer Joseph G. Totten, and construction was supervised by Major John Sanders. The fort was about the size and location of the previous star fort. It was in the shape of an irregular pentagon, with five small bastions at the corners, called "tower bastions" by Totten. Four of the sides were seacoast fronts, with three tiers of cannon on each, two casemated tiers in the fort and one barbette tier on the roof. The irregular shape provided for more cannon on the east-facing fronts, where the deeper channel was. A total of 123 heavy cannon could be mounted on the seacoast fronts, with 15 more in the bastions. The long rear front was called a "gorge wall", with two tiers totaling 68 loopholes for muskets and a tier of 11 cannon on the roof. In the center of this wall was the sally port, the only entrance to or exit from the fort. Twenty short-range flank howitzers could be mounted in the bastions to defeat attacks on the curtain walls. Thus, the fort had positions for 169 cannon. The fort also had a moat, with a tide gate on a canal from the river to control the moat's level.[34]

1861–1885

Fort Delaware was used as a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederates for most of the Civil War. Convicted Union Army soldiers and local political prisoners were also held there. By August 1863 over 11,000 prisoners were on the island, and during the war a total of 33,000 were housed there at some time. About 2,500 prisoners died on Pea Patch Island during the war.[39] Half the total deaths were in a smallpox epidemic in 1863.[40] Many of the Confederate prisoners and Union guards who died at the fort are buried in the nearby Finn's Point National Cemetery in Pennsville, New Jersey.[41]

The Ten Gun Battery, briefly called Camp Reynolds or Fort Reynolds, was built from 1863 to 1864 on the property of 1st Lt. Clement Reeves of the 5th Delaware Volunteer Infantry, on the Delaware shore near Fort Delaware, now on the Fort DuPont property. Sgt. Bishop Crumrine of Young's Battery wrote, "This fortification is not properly a Fort but rather a water battery. Situated just across the river from Fort Delaware on the Delaware City side, it has five sides. The two longest sides being next to the river is a heavy breast work on which six 10-inch and four 15-inch Rodman guns are mounted."[42] The Civil War had shown that masonry forts were vulnerable to modern rifled cannon, particularly in the siege of Fort Pulaski near Savannah, Georgia in 1862.

New earthwork forts were built in the 1870s, including reconstruction of the Ten Gun Battery as the Twenty Gun Battery and the new Battery at Finn's Point, later the site of Fort Mott. Both were to house heavy guns and coast defense mortars, but were not completed or fully armed, as construction funding for forts was cut off in 1878.[43][44] In 1876 a mine casemate was built near the Twenty Gun Battery to control an underwater minefield, one of the first defenses of this type in the US.[45] A similar casemate was built around the same time at Fort Mifflin, but was not used.[46]

Endicott period

.jpg.webp)

The Board of Fortifications was convened in 1885 under Secretary of War William Crowninshield Endicott to develop recommendations for a full replacement of existing coast defenses. Most of its recommendations were adopted, and construction began in 1896 on new batteries and controlled minefields to defend the Delaware.[47][1]

Fort Delaware was modernized with a large new gun battery inside the stone fort and small-caliber batteries on and outside the fort. The other forts were on the shores flanking Pea Patch Island. Fort Mott was built as both a seacoast fort and to defend against a land attack, reusing some of the 1870s Finn's Point Battery. Fort DuPont received all-new gun batteries, including a battery for 16 mortars. The three forts became known as the Coast Defenses of the Delaware. This appears to have initially been an Artillery District, was renamed as a Coast Defense Command in 1913, and again renamed as a Harbor Defense Command in 1925.[3][5]

Fort Delaware had a battery of three 12-inch (305 mm) guns on disappearing carriages inside the fort; three batteries of two 3-inch (76 mm) guns each (two batteries on the roof of the fort) served as mine defense guns, protecting controlled minefields from minesweepers.[32] Disappearing carriages folded down to hide the gun behind a parapet for reloading. In 1892 a mine control casemate was built on the north end of Pea Patch Island for a minefield between Fort Delaware and Fort Mott. Fort DuPont controlled another minefield in the other channel.[45] In 1898 a battery of two 4.72-inch (120 mm) guns was added outside the fort due to the Spanish–American War; most of the Endicott batteries in the area were years from completion and it was feared the Spanish fleet would bombard the U.S. east coast.[48]

Fort DuPont had a battery of sixteen 12-inch (305 mm) mortars in an "Abbot Quad" arrangement for concentrated fire. Two 12-inch (305 mm) guns on barbette carriages and two 8-inch (203 mm) guns on disappearing carriages were in an unusual arrangement: the 12-inch guns were on either side of the pair of 8-inch guns. Two two-gun batteries, one with 5-inch (127 mm) guns and one with 3-inch guns, completed the armament.[43]

Fort Mott had two three-gun batteries of disappearing guns, one with 12-inch (305 mm) guns and one with 10-inch (254 mm) guns. Two batteries of two 5-inch (127 mm) guns each flanked the heavy batteries. Under the 5-inch battery at the north end of the gun line was Battery Edwards, with two 3-inch mine defense guns in large casemates rebuilt from earlier (1872) magazines. These casemated light guns were a unique installation in US forts of this era, in which virtually all emplacements were open-top.[44][49] Fort Mott was also unusual for the Endicott period in being designed to resist a land attack. A parados (basically an artificial hill) and moat were placed behind the gun batteries to impede an assault from the landward side. Also, the fort's four 5-inch guns were in mounts permitting 360° of fire, and were sited to fire on attackers flanking the parados.[50]

Unusually, weapons were removed from CD Delaware prior to the US entry into World War I to arm higher-priority defenses. In 1910–1913 a 5-inch gun battery at Fort Mott was relocated to Fort Ruger, Hawaii.[44] Four mortars from Fort DuPont were transferred to the same fort in 1914.[43] Removal of mortars in the cramped Abbot Quad battery improved reload times.

World War I

The American entry into World War I brought many changes to the Coast Artillery and the Coast Defenses of the Delaware (CD Delaware). Numerous temporary buildings were constructed at the forts to accommodate the wartime mobilization. As the only component of the Army with heavy artillery experience and significant manpower, the Coast Artillery was chosen to operate almost all US-manned heavy and railway artillery in that war. At most coast defense commands, garrisons were drawn down to provide experienced gun crews on the Western Front, mostly using French- and British-made weapons. At least one company from CD Delaware was used to form the 60th Artillery (Coast Artillery Corps), which saw action in France.[51][52][53] Some weapons were removed from forts with the intent of getting US-made artillery into the fight. 5-inch and 6-inch guns became field guns on wheeled carriages.[54] 12-inch mortars were also removed as railway artillery or to improve reload times by reducing the number of mortars in a pit from four to two; this happened at Fort DuPont to provide mortars elsewhere. The remounted 5-inch and 6-inch guns were sent to France, but their units did not complete training in time to see action.[51]

In 1917–1918 a number of weapons were relocated away from CD Delaware; only two were returned. Four mortars from Fort DuPont were used to arm Fort Rosecrans in San Diego, California. The remaining 5-inch guns at Fort Mott were removed for use as field guns.[44] At Fort DuPont, the pair of 5-inch guns were transferred to an "emergency battery" at Fisherman's Island, Virginia in 1917–1918. The pair of 12-inch guns were moved to Fort Hamilton, New York and the pair of 8-inch guns were removed for potential service as railway artillery.[43] The 4.7-inch guns at Fort Delaware were sent to San Francisco for use on Army troop transports; they were returned to Fort Delaware in 1919 but were soon removed from service and used as war memorials.[32]

In 1918 a two-gun antiaircraft battery armed with M1917 3-inch (76 mm) guns on fixed mounts was built at Fort DuPont.[45]

In 1917 one 6-inch gun each was placed at the Cape May Military Reservation and the Cape Henlopen Military Reservation, at the mouth of Delaware Bay. These guns were removed after the war.[47][1]

References indicate that the authorized strength of CD Delaware in World War I was 11 companies, including one from the New Jersey National Guard.[55]

Between the wars

In 1920 Fort Saulsbury was completed near Slaughter Beach and Milford, Delaware, with two batteries of a new type: 12-inch guns on long-range barbette carriages. These carriages increased the guns' range from 18,000 yards (16,000 m) to 27,500 yards (25,100 m).[56] There were two guns per battery, without cover but positioned where they were difficult to see from the ocean. Each battery had a large earth-covered concrete bunker for ammunition and fire control. These batteries began construction in 1917, were completed in 1920, and accepted for service in 1924. The long-range carriage was developed in response to the rapid improvement of dreadnought battleships in the naval arms race. Fort Saulsbury was an example of new defenses being built seaward as gun ranges increased, and largely superseded the other heavy weapons in HD Delaware. However, no guns were removed elsewhere, and the HDC headquarters remained at Fort DuPont. Fort Saulsbury seems to have been unaccompanied by smaller-caliber guns or a minefield.[45][57]

In 1919-1920 several weapon types were declared obsolete and removed from coast defenses. These included all 5-inch guns, all Armstrong guns (6-inch and 4.72-inch), and 3-inch M1898 guns. Only in rare cases were these weapons replaced. In CD Delaware this meant the removed 5-inch guns were not returned, the 4.72-inch guns were removed as war memorials, and three 3-inch batteries were scrapped. These were the two batteries on top of Fort Delaware and Fort Mott's unique casemated 3-inch battery.[32][44]

On 1 July 1924 the harbor defense garrisons completed the transition from a company-based organization to a regimental one, and on 9 June 1925 the commands were renamed from "Coast Defenses..." to "Harbor Defenses..." as Harbor Defense Commands.[3][5] The 3rd Battalion, 7th Coast Artillery of the regular army became the garrison of HD Delaware, which was in caretaker status between the wars. Headquarters and Headquarters Battery (HHB) 3rd Battalion and Battery E, 7th CA were the initial caretaker units. On September 1, 1935 the HHB was deactivated. In May 1936 the 261st Coast Artillery Battalion (Harbor Defense) (HD) of the Delaware National Guard was organized as the National Guard component of HD Delaware.[58][59]

World War II

Early in World War II numerous temporary buildings were again constructed at the forts to accommodate the rapid mobilization of men and equipment. In 1940–41 the 21st Coast Artillery Regiment was mobilized at Fort DuPont with a strength of one battalion to garrison the Harbor Defenses of the Delaware (HD Delaware). On January 27, 1941 the 261st Coast Artillery Battalion was activated and moved to Fort DuPont, with elements moving to Fort Miles on June 5, 1941. On April 15, 1941 the 21st CA deployed 155 mm gun batteries at Fort Miles and activated Fort Saulsbury.[60][58][59]

In December 1940 Fort Delaware's three 12-inch guns were removed. Two were used to arm Battery Reed, Fort Amezquita in the Harbor Defenses of San Juan, Puerto Rico; the third went to Watervliet Arsenal, New York.[32][61]

On April 2, 1941 Fort Mott's three 10-inch (254 mm) guns and carriages were transferred to Canada under the Lend-Lease agreement. Two of their barrels remain in place as of 2018 at Fort Cape Spear, St. John's, Newfoundland. The third gun was deployed to Fort Prével on the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec, and was scrapped after the war.[62]

The first batteries at Fort Miles and Cape May were four mobile 155 mm GPF guns each, deployed in April 1941 at Fort Miles and some time later in 1941 at the Cape May Military Reservation in New Jersey. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 building up Fort Miles became a higher priority. By mid-1942 concrete "Panama mounts" were completed for the 155 mm gun batteries.[63][64][1] On March 14, 1942 Battery C of the 52nd Coast Artillery (CA) (Railway) regiment arrived with four 8-inch (203 mm) railway guns. By September 10 this battery was joined by Battery D with the same armament; Batteries C and D were initially the 2nd Battalion of the 52nd CA, and were redesignated as the 287th Coast Artillery (Railway) Battalion on May 1, 1943.[58]

After the Fall of France in 1940 the Army decided to replace all existing heavy coast defense guns, except the long-range 12-inch guns, with 16-inch guns. In HD Delaware this meant an all-new fort at the mouth of Delaware Bay at Cape Henlopen, later named Fort Miles. The fort's largest armament was Battery 118, later named Battery Smith, built in 1942–43 with two ex-Navy 16-inch (406 mm) Mark 2 guns. This battery effectively superseded all other heavy weapons in HD Delaware, the third time new defenses were built seaward as gun ranges increased. An additional 16-inch battery, Battery 119, was proposed but not built. Instead, two of Fort Saulsbury's 12-inch guns were relocated to Fort Miles as Battery 519, completed in August 1943. These batteries at Fort Miles were built casemated, with heavy concrete enclosures for protection against air attack. Fort Miles also had a controlled minefield.[47][1]

The 16-inch batteries were supplemented by new two-gun 6-inch (152 mm) batteries. These included heavy earth-covered concrete bunkers for ammunition and fire control, with the guns protected by open-back shields. The guns for these batteries were mostly the 6-inch guns removed in World War I for field service and stored since that war; a new 6-inch gun M1 of similar characteristics was developed when this supply of guns began to run out. Three of these batteries were in HD Delaware, two at Fort Miles (Batteries 221 and 222) and one at Cape May Military Reservation, New Jersey (Battery 223).[47]

Three 90 mm gun (3.5 inch) Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat (AMTB) batteries were built in HD Delaware. These had 90 mm dual-purpose (anti-surface and anti-aircraft) guns. Each battery was authorized two 90 mm guns on fixed mounts, two on towed mounts, and two single 40 mm Bofors guns, although the weapons on hand may have varied. Two batteries were at Fort Miles and one was at Cape May.[47]

Following mobilization in 1940 HD Delaware was subordinate to First Army. On 24 December 1941 the Eastern Theater of Operations (renamed the Eastern Defense Command three months later) was established, with all east coast harbor defense commands subordinate to it, along with antiaircraft and fighter assets. This command was disestablished in 1946.[65]

The US Navy also participated in defending the Delaware with net defenses and a defensive boom at Reedy Island.[43][66] Submarine-detecting indicator loops were also used, with a station at Fort Miles.[67]

As Fort Miles' batteries were completed, the remaining weapons at the forts on and near Pea Patch Island were removed or scrapped. Fort DuPont's mortars were effectively out of service in 1941; in December 1942 the carriages were ordered scrapped, followed by the mortars in April 1943.[43] Fort Mott's remaining three 12-inch guns were ordered scrapped in December 1943; combined with relocations of the remaining 3-inch batteries this left the upper river forts with no armament.[44]

The increasingly remote threat of an enemy surface attack and an Army-wide shift from a regimental to a battalion-based system meant drawdowns in HD Delaware, starting in early 1944. The 261st Coast Artillery Battalion was deactivated with most personnel transferred to the 21st Coast Artillery Regiment in March 1944.[68] In April 1944 the 287th Coast Artillery Battalion (Railway) was moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina and later was reorganized as a field artillery battalion.[69] In October 1944 the 21st CA was itself reduced to a battalion with the same number and placed under the Eastern Defense Command, and on 1 April 1945 was inactivated, with remaining personnel at Fort Miles transferring to the Harbor Defenses of the Delaware.[70][71]

Cold War

Following the war, it was soon determined that gun defenses were obsolete, and they were scrapped by the end of 1948, with remaining harbor defense functions turned over to the Navy.[47] In 1950 the Coast Artillery Corps and all Army harbor defense commands were dissolved. Today the Air Defense Artillery carries the lineage of some Coast Artillery units. For air defense in the Cold War, an extensive system of 90 mm antiaircraft guns was emplaced in the Philadelphia area in the early 1950s,[72][73][74] followed by Nike missile systems in the late 1950s (see List of Nike missile sites#Pennsylvania and List of Nike missile sites#New Jersey). The Nike missiles were removed in the early 1970s. Battery 221 a.k.a. Battery Herring, originally covered with sand like all the other batteries, was excavated and expanded for use as a U.S. Navy SOSUS station during the Cold War as part of Naval Facility (NAVFAC) Lewes. It is now abandoned.

Present

As of 2018, Fort Mott, Fort Delaware, and Delaware City are connected by a seasonal passenger ferry, the Forts Ferry Crossing.[75] Fort Delaware and Fort Mott are both well preserved as state parks, with many parts accessible to the public, and active living history programs. Fort DuPont is a state park. Fort Saulsbury is well preserved, but is on private property and not normally accessible to the public. Fort Miles is now Cape Henlopen State Park, and has some of the best preserved and restored World War II coast defense batteries in the United States. The fort also has an active living history group.[76] The 12-inch battery has a remounted gun, and a 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 gun formerly on USS Missouri (BB-63) has been remounted as a commemorative display; as of December 2018 part of the wreckage from USS Arizona (BB-39) was planned to be added.[77] There are also a few other coast artillery weapons at the fort. Battery Hunter a.k.a. Battery 222 is in use currently as a Hawk Watch station. Several fire control towers remain, particularly around Fort Miles; at least one is publicly accessible.[66]

Heraldry

Harbor Defenses of the Delaware

- Blazon

- Symbolism: The history of this region shows that it was colonized and occupied by the Swedish, Dutch, and English, who are shown on these arms by the three lions' heads, each of those countries having a gold lion on their coat of arms. The color blue is common to all three flags and also to the flag of the United States. The griffin's head is taken from the crest of Lord Delaware for whom the state, river, and defenses were named.[78]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harbor Defenses of the Delaware at CDSG.org

- ↑ Stanton, pp. 455-481

- 1 2 3 Coast Artillery Organization: A Brief Overview at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ↑ Rinaldi, pp. 165-166

- 1 2 3 Berhow, pp. 427-434

- ↑ Munroe, John A (2006). "3. The Lower Counties on The Delaware". History of Delaware (5th, illustrated ed.). University of Delaware Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-87413-947-1.

- ↑ Kyriakodis, Harry (2011). "16. At Washington Avenue". Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62584-188-9.

- ↑ Dorwart 1998, pp. 9–13.

- ↑ Scull 1881, pp. 414–417.

- 1 2 Liggett & Laumark 1979, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 Roberts 1988, pp. 511–512.

- ↑ "The Plank House". www.marcushookps.org. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ Roberts 1988, pp. 505–506, 511–512, 686–687.

- ↑ Black 1998, pp. 117–121.

- ↑ Higginbotham 1983, pp. 181–188.

- ↑ Jackson 1986.

- ↑ Fort Mercer at RevolutionaryWarNewJersey.com

- ↑ Chartrand 2016, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Boatner 1994, p. 384.

- ↑ Chartrand 2016, p. 29.

- ↑ Ketchum 1997, pp. 360–368.

- ↑ Paterson 2009, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Douglas Southall Freeman, Washington (1968) pp. 381–82

- ↑ Paterson 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ Wilkinson 1960–1961, p. 179.

- ↑ Wade 2011, p. 17.

- ↑ Roberts 1988, pp. 686–687.

- ↑ Wade 2011, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Wade 2011, pp. 78–79, 87, 224–225.

- 1 2 Dobbs, Kelli W.; Siders, Rebecca J. Fort Delaware Architectural Research Project. Newark, DE: University of Delaware, Center for Historic Architecture and Design, 1999.

- ↑ Roberts 1988, pp. 129–130.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fort Delaware at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Delaware City Battery at American Forts Network

- 1 2 3 4 Weaver 2018, pp. 171–176.

- 1 2 American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, From the First Session to the Second Session of the Eighteenth Congress, Inclusive. Commencing December 27, 1819, and ending February 28, 1825. Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1834.

- ↑ Mackie, Brendan., Peter K. Morrill, Laura M. Lee. Images of America: Fort DuPont. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2011., p 14.

- ↑ West Publishing Company (1897). "The Federal Cases: Comprising Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States from the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the Federal Reporter, Arranged Alphabetically by the Titles of the Cases and Numbered Consecutively, Book 30". Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ↑ Dobbs, Kelli W., Life Outside These Walls: A Study of Community Life on Pea Patch Island, Fort Delaware, 1848-1860. Newark, DE: University of Delaware, Spring 1999.

- ↑ Jamison, Jocelyn P., They Died at Fort Delaware 1861-1865: Confederate, Union and Civilian. Delaware City, DE: Fort Delaware Society, 1997

- ↑ Jamison, pp. 91–94

- ↑ Finn's Point National Cemetery at US Veterans Administration

- ↑ Crumrine, Bishop. "Letters Sent 1862–1865." Washington and Jefferson College, U. Grant Miller Library, January 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fort DuPont at FortWiki.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Fort Mott - FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts". www.fortwiki.com.

- 1 2 3 4 Delaware forts at American Forts Network

- ↑ Fort Mifflin at American Forts Network

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Berhow, pp. 210-211

- ↑ Congressional serial set, 1900, Report of the Commission on the Conduct of the War with Spain, Vol. 7, pp. 3778–3780, Washington: Government Printing Office

- ↑ Berhow 2015, p. 200.

- ↑ 1921 maps of HD Delaware at CDSG.org

- 1 2 Coast Artillery Corps Units in France in WWI

- ↑ 60th Artillery in WWI at Rootsweb.com

- ↑ Rinaldi 2004, p. 163.

- ↑ Williford 2016, pp. 92–99.

- ↑ Rinaldi 2004, p. 165.

- ↑ Berhow 2015, p. 61.

- ↑ Fort Saulsbury at FortWiki.com

- 1 2 3 Gaines Regular Army, pp. 7-8, 14

- 1 2 National Guard Coast Artillery regiment histories at the Coast Defense Study Group

- ↑ Stanton 1991, pp. 459, 472, 492.

- ↑ Berhow 2015, pp. 210, 226.

- ↑ Battery Harker at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Fort Miles at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Cape May Military Reservation at FortWiki.com

- ↑ Conn, pp. 33-35

- 1 2 Harbor Defenses of the Delaware at American Forts Network

- ↑ Indicator loop station at Fort Miles

- ↑ Stanton 1991, p. 492.

- ↑ Stanton 1991, p. 493.

- ↑ Stanton 1991, pp. 459, 484.

- ↑ 21st Coast Artillery at FortMiles.org

- ↑ "AAA gun sites at Ed-Thelen.org". Archived from the original on 2020-09-16. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- ↑ Cold War AAA Defenses of Philadelphia at American Forts Network

- ↑ Cold War AAA Defenses of Philadelphia in New Jersey at American Forts Network

- ↑ Forts Ferry Crossing at VisitNJ.org

- ↑ Fort Miles.org

- ↑ ""U.S.S. Arizona wreckage to join U.S.S. Missouri gun at Fort Miles" at CoastalPoint.com". Archived from the original on 2019-04-18. Retrieved 2019-01-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Coat of Arms for the Harbor Defenses of the Delaware, Coast Artillery Journal, August 1928, vol. 69 no. 2, p. 161

Bibliography

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Black, Jeremy (1998). War for America: The Fight for Independence, 1775–1783. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-2808-3.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Chartrand, René (2016). Forts of the American Revolution 1775–83. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4728-1445-6.

- Conn, Stetson; Engelman, Rose C.; Fairchild, Byron (2000) [1964]. Guarding the United States and its Outposts. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- Dorwart, Jeffery (1998). Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia: An Illustrated History. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1644-8.

- Gaines, William C., Coast Artillery Organizational History, 1917-1950, Regular Army regiments, Coast Defense Journal, vol. 23, issue 2

- Gaines, William C., Historical Sketches Coast Artillery Regiments 1917-1950, National Guard Army Regiments 197-265

- Higginbotham, Don (1983). The War of American Independence. Northeastern Classics. ISBN 978-0-9303504-4-4.

- Jackson, John (1986). Fort Mifflin: Valiant Defender of the Delaware. Old Fort Mifflin Historical Society Preservation Committee.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1973). The Winter Soldiers. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-05490-4. OCLC 640266.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623.

- Liggett, Barbara; Laumark, Sandra (1979). "The Counterfort at Fort Mifflin". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. Association for Preservation Technology International (APT). 11 (1): 37–74. doi:10.2307/1493677. JSTOR 1493677.

- Paterson, Thomas G.; et al. (2009). American Foreign Relations, Volume 1: A History to 1920. Cengage Learning. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-0-547-22564-7.

- Rinaldi, Richard A. (2004). The U. S. Army in World War I: Orders of Battle. General Data LLC. ISBN 0-9720296-4-8.

- Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

- Scull, G. D., ed. (1881). "The Montresor Journals". Collection for the Year 1881. Collections of the New-York Historical Society ... 1881. Publication fund series.[v. 14]. New York Historical Society.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1991). World War II Order of Battle. Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-775-9.

- Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794–1815. CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

- Weaver, John R. II (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867 (2nd ed.). McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.

- Wilkinson, Norman B. (1960–1961). "The Forgotten "Founder" of West Point". Military Affairs. Society for Military History. 24 (4): 177–188. doi:10.2307/1984876. JSTOR 1984876.

- Williford, Glen (2016). American Breechloading Mobile Artillery, 1875-1953. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7643-5049-8.

Further reading

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Morgan, Mark L.; Berhow, Mark A. (2010). Rings of Supersonic Steel: Air Defenses of the United States Army 1950-1979 (3rd ed.). Hole in the Head Press. ISBN 978-09761494-0-8.

External links

- Fort Delaware Society

- Fort Mott State Park

- Fort DuPont State Park

- Fort Miles.org

- The Fort Miles Historical Association

- Cape Henlopen State Park

- Map of HD Delaware at FortWiki.com

- Insignia of the Coast Artillery Corps at the Coast Defense Study Group

- American Forts Network, lists forts in the US, former US territories, Canada, and Central America

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts