| Astrology |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

| Astrological signs |

| Symbols |

Heliocentric astrology is an approach to astrology centered around birth charts cast using the heliocentric model of the Solar System, positioning the Sun at the center.[1] In contrast to geocentric astrology, which places Earth at the center, heliocentric astrology interprets planetary positions from the Sun's vantage point. While geocentric astrology considers elements like the ascendant, midheaven, houses, Sun, Moon, and planetary aspects, heliocentric astrology focuses primarily on planetary aspects and configurations. Astrologers often use this method in conjunction with geocentric astrology to access insights beyond the traditional framework.

The roots of heliocentric astrology extend back to Copernicus's 16th-century work on heliocentrism. Early pioneers like Andreas Aurifaber and later practitioners like Joshua Childrey challenged geocentric perspectives during the 17th century. They proposed that astrology could align with contemporary natural philosophy, finding support from figures within the Royal Society. In the late 19th century, Holmes Whittier Merton's book Heliocentric Astrology: Or, Essentials of Astronomy and Solar Mentality emphasized the relationship between astronomy and the Sun's influence on mentality.

Description

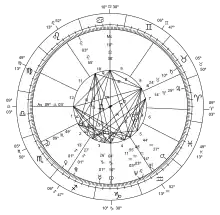

Most forms of astrology are geocentric. The geocentric horoscope is drawn with the Earth at the center, and the planets are placed around the cartwheel in the positions that they would appear in the sky as seen by a person who is looking at them from the center of the Earth.[2]

The Greek language word "helios" means the Sun.[3] Heliocentric astrology draws birth charts with the Sun at the center, and the planets are placed around the cartwheel in the positions that they would appear if someone looked at them from the center of the Sun.[4]

Geocentric astrology relies heavily on the ascendant, midheaven, houses, the Sun, the Moon, planetary aspects (astrological aspects) and placements of birth planets in the houses and signs.[5] But heliocentric astrology does not have houses (due to not having a location on the surface of the Sun to compute houses for), the ascendant or midheaven,[6] and there are no lunar nodes or retrograde motion in heliocentric birth charts. Instead, heliocentric astrology depends primarily on planetary aspects and configurations for interpretation.[7] For this reason, no astrologer uses heliocentric astrology to the exclusion of geocentric astrology. But supporters of heliocentric astrology believe that it can reveal much that geocentric astrology cannot and therefore recommend that all astrologers add heliocentric astrology chart analysis as a supplement to geocentric astrology.[8]

History

The first astrologer to consider applying the new heliocentric model of Copernicus (1473–1543) was Andreas Aurifaber (1514–1559).[9]

In the early 1650s, under the Protectorate, Joshua Childrey (1623–1670) was working with Thomas Streete on astrological tables.[10] He published two short astrological works:[11]

- Indago Astrologica, or a brief and modest Enquiry into some principal points of Astrology, 1652, and

- Syzygiasticon instauratum; or an ephemeris of the places and aspects of the planets as they respect the ⊙ as Center of their Orbes. Calculated for 1653 (1653).

In the Indago Astrologica Childrey, though in other ways a convinced Baconian, argued that Francis Bacon's geocentric model of the cosmos was incorrect.[12] Subsequently he was associated with a group who wished to reform astrology along lines (the heliocentric model and the Baconian method) that would make it compatible with contemporary natural philosophy.[13] Vincent Wing's Harmonicon coeleste (1651) was a related initiative. Others involved were John Gadbury and John Goad. There were supporters of this direction from within the Royal Society, including Elias Ashmole and John Beale.[14][15][16]

In 1899, a book dedicated to the heliocentric form of astrology, Heliocentric Astrology: Or, Essentials of Astronomy and Solar Mentality by Holmes Whittier Merton, was published. A recent reprint (Merton 2017) is available.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Lewis (2003).

- ↑ Vedra (1918), p. 10.

- ↑ Vedra (1918), p. 127.

- ↑ Vedra (1918), p. 13.

- ↑ Hall (2018).

- ↑ Sedgwick (1990), p. 87.

- ↑ Sedgwick (1990), pp. 87ff.

- ↑ Erlewine (n.d.).

- ↑ Green (2010).

- ↑ Curry, Patrick. "Streete, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53850. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Stephen (1887).

- ↑ North (1989), pp. 27–8.

- ↑ Burns (2018), p. 305.

- ↑ Curry, Patrick. "Partridge". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21484. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Curry, Patrick. "Hunt, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53886. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Curry, Patrick. "Gadbury, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10265. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Works cited

- Burns, William E., ed. (2018). Astrology Through History: Interpreting the Stars from Ancient Mesopotamia to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1440851421.

- Erlewine, Michael (n.d.). "The Value of the Heliocentric/Geocentric Comparison". Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- Green, J. (2010). "The First Copernican Astrologer: Andreas Aurifaber's Practica for 1541". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 41 (2): 157–165. Bibcode:2010JHA....41..157G. doi:10.1177/002182861004100201. S2CID 119027458.

- Hall, Molly (April 30, 2018). "Understanding the Basics of Astrology". liveabout dotcom. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- Lewis, James R. (2003). "Heliocentric Astrology". The Astrology Book: The Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences. Visible Ink Press. pp. 297–299. ISBN 978-1578592463.

- Merton, Holmes Whittier (2017) [1899]. Heliocentric Astrology: Or, Essentials of Astronomy and Solar Mentality, with Tables of Ephemeris to 1910. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1473340442.

- North, John (1989). The Universal Frame: Historical Essays in Astronomy, Natural Philosophy and Scientific Method. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-907628-95-8.

- Sedgwick, Phillip (1990). The Sun at the Center: A Primer on Heliocentric Astrology. Llewellyn Modern Astrology Library. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0875427386.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1887). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 10. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Vedra, Yarmo (1918). Heliocentric Astronomy or Essentials of Astronomy and Solar Mentality. Philadelphia: David McKay, Publisher.

Further reading

- Hutchison, K. (2012). "An Angel's View of Heaven: The Mystical Heliocentricity of Medieval Geocentric Cosmology". History of Science. 50 (1): 33–74. doi:10.1177/007327531205000102. S2CID 142480611.

- Johnston, Stephen (2006), "Like father, like son? John Dee, Thomas Digges and the identity of the mathematician", in Clucas, Stephen (ed.), John Dee: Interdisciplinary Studies in English Renaissance Thought, International Archives of the History of Ideas / Archives internationales d’histoire des idées, vol. 193, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 65–84, doi:10.1007/1-4020-4246-9_4, ISBN 1-4020-4245-0, retrieved 2022-12-15 – via www.mhs.ox.ac.uk

- Kremer, Richard L. (2010). "Calculating with Andreas Aurifaber: A new Source for Copernican Astronomy in 1540". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 41 (4): 483–502. Bibcode:2010JHA....41..483K. doi:10.1177/002182861004100404. S2CID 119535232.

- Michelsen, Neil F., ed. (2007). The American Heliocentric Ephemeris 2001-2050. Starcrafts Pub. ISBN 978-0976242253.

- Westman, R. S. (2011). "The Emergence of Kepler's Copernican Representation". The Copernican Question: Prognostication, Skepticism, and Celestial Order (1st ed.). University of California Press. pp. 309–335. ISBN 978-0-520-94816-7. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1pn8ng.16.

External links

- Online Books by Holmes Whittier Merton at the University of Pennsylvania Online Books Page.