The Heruli (or Herules) were an early Germanic people. Possibly originating in Scandinavia, the Heruli are first mentioned by Roman authors as one of several "Scythian" groups raiding Roman provinces in the Balkans and the Aegean Sea, attacking by land, and notably also by sea. During this time they reportedly lived near the Sea of Azov.

From the late 4th century AD the Heruli were one of the peoples that were brought into the fold of the Hunnic Confederation of Attila. By 454, after the death of Attila, they established their own kingdom on the Middle Danube, and Heruli also participated in successive conquests of Italy by Odoacer, Theoderic the Great, Narses and probably also the Lombards. However, their independent kingdom was destroyed by the Lombards by the early 6th century AD. A part of this population subsequently became established inside the Roman empire near Belgrade, and continued contributing fighting men to the Eastern Roman Empire, and participating in Balkan and Italian conflicts.

With their last kingdom eventually dominated by Rome, and smaller groups integrated into larger political entities, the Heruli disappeared from history around the time of the conquest of Italy by the Lombards.

Name

The name of the Heruli is sometimes spelled as Heruls, Herules, Herulians or Eruli.[1] In the earliest mentions of them in 4th century records, they are called Eluri instead, leading to some doubts about whether they were the same people.[2]

The name Heruli was often written without "h" in Greek (Ἔρουλοι, 'Erouloi') and Latin (Eruli), and is sometimes thought to be Germanic and related to the English word earl (see erilaz) implying that it was an honorific military title.[3] There is even speculation that the Heruli were not a normal tribal group but a brotherhood of mobile warriors, though there is no consensus for this old proposal, which is based only on the name etymology and the reputation of Heruli as soldiers.[4]

Language

The Heruli are believed to have spoken a Germanic language.[5] Personal names are one of the only direct sources of evidence for this.[6] Some attested Heruli names are almost certainly Germanic,[7][8] and similar to Gothic names, but a large number are not easily attributed to any specific language family.[9][10]

Given their association with the Goths, the Heruli may have spoken an East Germanic language, related to the Gothic language.[11][12][13] Alternatively however, given their proposed connections to Scandinavia, it has also been proposed that they spoke a North Germanic language.[14]

Classification

When first mentioned by Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, the Heruli were referred to as "Scythians", along with the Goths and allied tribes.[15] The use of this term for Heruli and Goths probably began as early as Dexippus, most of whose work is now lost.[16] The use of this term does not give us any clear linguistic classification.[17]

In late antiquity, the Gepids, Vandals, Rugii, Sciri, the non-Germanic Alans and the actual Goths, were all classified by Roman ethnographers as "Gothic" peoples, and modern historians generally consider the Heruli to be one of these.[18] While historians such as Walter Goffart have pointed out that the Herules are never included in the lists of "Gothic peoples" of Procopius, Mihail Zahariade has shown that the Latin and Greek sources not only distinguish the Heruli (Elouroi in this period) from the Goths during their first 3rd century seaborne offensive (see below), but also Zonaras specifically stated that the Heruli were of Gothic stock — a categorization implied by other chroniclers of those events when they refer to Goths.[19]

None of these eastern peoples were considered Germanic by Roman ethnographers at the time.[20] However, in modern scholarship the Heruli are usually classified as a Germanic people.[21][22][23][24] On account of having likely spoken an East Germanic language, the Heruli are often more specifically classified as an East Germanic people.[25][26]

History

Origins

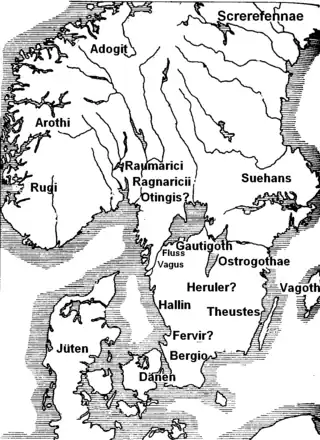

Although contemporary records locate the Heruli first near the Sea of Azov, and later on the Middle Danube, their origins are traditionally sought in north-central Europe,[5] possibly Scandinavia.[24][27][28][29]

The main reason for this is that in his 6th century work Getica, the historian Jordanes, based in Constantinople, wrote that the Heruli had been driven out of their homeland in Scandinavia by the Danes.[30] This has been read as implying Heruli origins in the Danish isles or southernmost Sweden. The reliability and correct interpretation of this passage in the Getica is, however, disputed.[31][32] On the other hand, his contemporary Procopius recounted a migration of a sixth-century group of Heruli noblemen to Thule (which for him was the same as Scandinavia), from their "homeland" on the Middle Danube.[33] Later, Danubian Heruli found new royalty among these northern Heruli who had previously migrated northwards.[33] This account has been seen as implying an old and continuous connection between the Heruli and Scandinavia, although some recent scholars are skeptical of this interpretation, and have noted that Procopius does not depict the Heruli as returning to a homeland, but as leaving their homeland.[32][31]

Ellegård has proposed that the Danish expulsion of the Heruli might have happened in the 6th century, but been an expulsion of the immigrants from the Danube: "the only thing we can say with reasonable certainty is that a small group of Eruli lived there for some 38-40 years in the first half of the 6th century A.D.". He proposes that the evidence makes it most likely that the Heruli were "a loose group of Germanic warriors which came into being in the late 3rd century in the region north of the Danube limes that extends roughly from Passau to Vienna".[29]

On the Pontic-Caspian steppe

Before the earliest contemporary records of them, the Heruli are believed to have migrated towards the region north of the Black Sea in the 3rd century AD. Their better known neighbours there, the Goths, and possibly also their later Danubian neighbours Rugii, may have carried out a similar migration at this time. The Goths and their allies replaced the Sarmatians as the dominant power north of the Black Sea. The Sarmatians had in the 1st century AD partly been replaced the Bastarnae, who are believed to have spoken a Germanic language. The arrival of the Heruli has thus been seen as part of a bigger cultural shift in this region, involving the migration from the northwest of Germanic peoples, who replaced the Sarmatians as the dominant power in the region.[34]

The first relatively clear mention of the Heruli by Graeco-Roman writers concerns two major campaigns into the Balkans of 267/268 and 269/270.[35] Goths, Heruli (referred to as "Eluri", Ἔλουροι, in the oldest sources), and other "Scythian" peoples from the region of the Sea of Azov, took control of Black Sea Greek cities, and gained a fleet that they used to launch raids along the northern Black Sea and as far as Greece and Asia Minor. These invasions began in the reign of Gallienus (260-268 AD), and continued until at least 269 during the reign of Marcus Aurelius Claudius, who subsequently took up the title "Gothicus" due to his victory.[36][37]

In 267, Heruli (Αἴρουλοι) commanded a naval attack from the Sea of Azov, past the Danube delta, and into the straits of the Bosphorus (the area of modern Istanbul). They took control of Byzantion and Chrysopolis before retreating to the Black Sea. Emerging to raid Cyzicus, they subsequently entered the Aegean Sea, where they troubled Lemnos, Skyros and Imbros, before landing in the Peloponnese. There they plundered not only Sparta, the closest city to their landing site, but also Corinth, Argos, and the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia. Still within 267 they reached Athens, where local militias had to defend the city. It seems to have been the Heruli specifically who sacked Athens despite the construction of a new wall, during Valerian’s reign only a generation earlier. This was the occasion for a famous defense made by Dexippus, whose writings were a source for later historians.[38]

Further north, in 268, Gallienus defeated Heruli at the river Nestos using a new mobile cavalry, but as part of the surrender a Herulian chief named Naulobatus became the first barbarian known from written records to receive imperial insignia from the Romans, gaining the rank of a Roman consul. It is highly likely that these defeated Heruli were then made part of the Roman military.[39][40]

Recent researchers such as Steinacher now have increased confidence that there was a distinct second campaign which began in 269, and ended in 270.[41] Later Roman writers reported that thousands of ships left from the mouth of the Dnieper, manned by a large force of various different "Scythian" peoples, including Peuci, Greutungi, Austrogothi, Tervingi, Vesi, Gepids, Celts, and Heruli. These forces divided into two parts in the Hellespont. One force attacked Thessaloniki, and against this group the Romans, led by Claudius now, had a major victory at the Battle of Naissus (Niš, Serbia) in 269. This was apparently a distinct battle from that at the Nessos. A Herulian chieftain named Andonnoballus is said to have switched to the Roman side, and this was once again a case where Heruli appear to have joined the Roman military. The second group sailed south and raided Rhodes, Crete, and Cyprus and many Goths and Heruli managed to return safely to harbor in the Crimea. Lesser attacks continued until 276.[42][43]

The Heruli are believed to have formed part of the Chernyakhov culture,[44] which, although dominated by the Goths and other Germanic peoples,[22] also included Bastarnae, Dacians and Carpi.[45] The Heruli are thus archaeologically indistinguishable from the Goths.[44][46]

Jordanes reports that the Heruli in the late 4th century AD were conquered by Ermanaric, king of the Greuthungian Goths.[47][48][49] Ermanaric's realm may also have included Finns, Slavs, Alans and Sarmatians.[45] Before being conquered by Ermanaric, Jordanes says that the Heruli were led by their king Alaric.[49] Herwig Wolfram has suggested that the future Visigothic king Alaric I may have been named after this Herulian king.[50]

Doubts have been raised about this earliest, Black Sea period in the history of the Heruli. The first author known to have equated these "Eruli" with the later "Eruli" was Jordanes, in the 6th century.[29]

The "western" Heruli, soldiers and pirates

The proposal that there may have been a Western kingdom of Heruli has posed a problem for scholars. This question arises because of the evidence of Heruli activity in the western Roman empire. The existence of this western kingdom is increasingly doubted.[51][52]

Heruli were already seen in western Europe before the empire of Attila, at the time of their first ambitious campaigns in the east. In 286 Claudius Mamertinus reported the victory of Maximian over a group of Heruli and Chaibones (known only from this one report[lower-alpha 1]) attacking Gaul.

It is believed that it was from this time that the Romans instituted a Herulian auxiliary unit, the Heruli seniores, who were stationed in northern Italy. This numerus Erulorum was a lightly-equipped unit often associated with the Batavian Batavi seniores. In 366 the Batavians and Heruli fought against the Alamanni near the Rhine, under the leadership of Charietto, who died in the battle, and then against Picts and Scoti in Britain. They were subsequently sent to fight Parthians in the east.[53][43]

In 405 or 406, a large number of barbarian groups crossed the Rhine, entering the Roman empire, and the Heruli appear in the list of peoples given by the historian Jerome. However, this list is sometimes thought to have drawn on historical lists for literary effect.

Later mentions of Heruli in western incidents where they were not clearly connected to the Roman military include two sea raids in northern Spain in the 450s, and the presence of Heruli at the Visigothic court of Euric in about 475.[51] The raids were reported by Hydatius. Sidonius Apollinaris mentions Heruli at the Visigothic court in 476, although this is in a poetic letter. Recent scholars such as Steinacher and Halsall have pointed out that this type of evidence is consistent with the internal military conflicts that were happening in the Roman empire during this period. Halsall, for example, writes that it "must at least be a possibility that their raid constituted part of a Romano-Visigothic offensive against the Sueves", who had been part of an invasion of the same area.[54] Steinacher demonstrates using examples from the period, including Charietto's life story, that barbarian soldiers could switch from being Roman soldier, to pirate, and back to soldier.[55]

The Gallo-roman poet Sidonius Apollinaris specifically imagined the Heruli he saw at Euric's court as oceanic sea-farers, but Steinacher argues that this raiding by sea was simply a logical strategy for Visigothic campaigns against the Iberian Suevi, and difficult to use as a proof that the Heruli had a coastal kingdom somewhere in the north.[56][57]

In reality, there is nothing special about attacks from the sea: various marauders employed such tactics at various points in history. It is just easier and not too dangerous.[58]

Given the writing style of Sidonius, this reference could also be "nothing more than a bookish reference to 3rd-century accounts of Herules attacking from the sea".[59]

Kingdom on the Middle Danube

In the early 5th century AD, large groups of peoples left the Middle Danube region, including the groups who crossed the Rhine in 405, many of whom eventually reached Iberia. Others crossed the Danube, like the forces of Radagaisus, who invaded Italy. During this period, the Huns and their allies begin to be found in this same area instead, having crossed the Carpathians from the east.[60] By 450 AD, the Heruli were firmly part of the Hunnic empire of Attila. The Gepids, Rugi, Sciri and many Goths, Alans and Sarmatians were also part of Attila's empire.[61] They were among the peoples who are reported as having fought for Attila at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

After the death of Attila, his sons lost power over the various peoples of his empire at the Battle of Nedao in 454. The centre of this alliance was now settled upon the Roman border north of the Middle Danube. Heruli who were possibly on the winning side with the Gepids, were subsequently among the several peoples now able to form a kingdom in that area. The Herulian kingdom, was established north of modern Vienna and Bratislava, near the Morava river, and possibly extending as far east as the Little Carpathians. They ruled over a mixed population including Suevi, Huns and Alans.[62] Compared to other Middle Danubian kingdoms in this period, Peter Heather has described this Heruli kingdom as "middle-sized", similar to the Rugian one, but "clearly not as militarily powerful, say, as the Gothic, Lombard, or Gepid confederations which generated much longer-lived political entities, and into which elements of the Rugi and Heruli were eventually absorbed".[63]

From this region the life story of Severinus of Noricum reports that the Heruli attacked Ioviaco near Passau in 480.[62] The Heruli do not appear in early lists of Odoacer's allies after Nedao, but benefited from the downfall of his people the Sciri. They established control on the Roman (south) side of the Danube, north of Lake Balaton in modern Hungary when they were apparently able to take over the kingdoms of the Suevi and Sciri, who had been under pressure from the Ostrogoths, who continued to press their old allies from the south.[64]

Odoacer, the commander of the Imperial foederati troops who deposed the last Western Roman Emperor Romulus Augustus in 476 AD came to be seen as king over several of the Danubian peoples including the Heruli, and the Heruli were strongly associated with his Italian kingdom. The Heruli on the Danube also took control of the Rugian territories, who had become competitors to Odoacer and been defeated by him in 488. However Heruli suffered badly in Italy, as loyalists of Odoacer, when he was defeated by the Ostrogoth Theoderic.

By 500 the Herulian kingdom on the Danube, apparently by now under a king named Rodulph, had made peace with Theoderic and become his allies.[65] Paul the Deacon also mentions Heruli living in Italy under Ostrogothic rule.[66] Peter Heather estimates that the Herulian kingdom could muster an army of 5,000-10,000 men.[67]

Theoderic's efforts to build a system of alliances in Western Europe were made difficult both by counter diplomacy, for example between Merovingian Franks and the Byzantine empire, and also the arrival of a new Germanic people into the Danubian region, the Lombards who were initially under Herule hegemony. The Herulian king Rodulph lost his kingdom to the Lombards at some point between 494 and 508.[68]

Later history

After the Middle Danubian Herulian kingdom was destroyed by the Lombards in or before 508, Herulian fortunes waned. According to Procopius, in 512 a group including royalty went north and settled in Thule, which for Procopius meant Scandinavia.[31] Procopius noted that these Heruli first traversed the lands of the Slavs, then empty lands, and then the lands of the Danes, until finally settling down nearby the Geats.[69][33] Peter Heather considers this account to be "entirely plausible" although he notes that others have labelled it a "fairy story", and given that it only appears in one source it is possible to deny its validity.[63]

Another Heruli group were assigned civil and military offices by Theoderic the Great in Pavia in north Italy.[70]

What happened to the main part of the Danubian Heruli has been difficult to reconstruct from Procopius, but according to Steinacher they first moved downstream on the Danube to an area where the Rugii had sought refuge in 488. Here they suffered famine. They sought refuge among the Gepids, but wanting to avoid being mistreated by them crossed the Danube came under East Roman authority.[71][72]

Anastasius Caesar allowed them to resettle depopulated "lands and cities" in the empire in 512. Modern scholars debate whether they were moved then to Singidunum (modern Belgrade), or first to Bassianae, and to Singidunum some decades later, by Justinian.[73] This area had been re-acquired by the empire from the Goths, who now ruled Italy from Ravenna.[74] Justinian integrated them into the empire as a buffer between the Romans and the more independent Lombards and Gepids to the north. Under his encouragement, the Herule king Grepes converted to Orthodox Christianity in 528 together with some nobles and twelve relatives.[75] Procopius who felt that this made them somewhat gentler, also showed in his account of the wars against the African Vandals, that some of them were Arian Christians.[76]

The Heruli were often mentioned during the times of Justinian, who used them in his extensive military campaigns in many countries including Italy, Syria, and North Africa. Pharas was a notable Herulian commander during this period. Several thousand Heruli served in the personal guard of Belisarius throughout the campaigns, and Narses also recruited from them. They were a participant in the Byzantine-Sasanian wars.

Grepes and most of his family had apparently died by the early 540s, possibly in the Plague of Justinian (541-542).[77][78] Procopius related that in the 540s the Heruli who had been settled in the Roman Balkans killed their own king Ochus and, not wanting the one assigned by the emperor, Suartuas, they made contact with the Heruli who had gone to Thule decades earlier, seeking a new king. Their first choice fell sick and died when they had come to the country of the Dani, and a second choice was made. The new king Datius arrived with his brother Aordus and 200 young men.[79][80] The Heruli who were sent against Suartuas defected with him and were supported by the empire. The supporters of Datius, two thirds of the Heruli, submitted to the Gepids.[77] This period of rebellion against Rome lasted approximately 545–548, the period immediately before conflict between their larger neighbours the Gepids and Lombards broke out, but this rebellion was repressed by Justinian.[81]

In 549, when the Gepids fought the Romans, and Heruli fought on both sides.[82] In any case after one generation in the Belgrade area, the Herulian federate polity in the Balkans disappears from the surviving historical records, apparently replaced by the incoming Avars.[80]

Peter Heather has written that:

by c.540 being a Herule had ceased to be the main determinant of individual behaviour; the Heruli had ceased to operate together on the basis of that shared heritage, and different Heruli were adopting different strategies for survival in the new political conditions which even caused them to fight on opposing sides. After c.540, we still find small groups called Heruli fighting for the East Romans in Italy, and it is noticeable that the Roman commanders were careful to appoint for them leaders of their own race. Thus some sense of identity probably remained. That said, we are clearly dealing with a few fragments of the original group, and, in the prevailing circumstances, Herule identity had no future.[83]

Sarantis however shows that the Belgrade-region Heruli continued to be recruited, and to play a role in local conflicts involving the Gepids and Lombards, into the 550s. Suartas, a Herule general for the Romans, led Herule forces against the Gepids in 552 for example.[84] However it appears that by this period the semi-independent Heruli near Belgrade became Roman provincials.[85]

In 566, Sinduald, a Herule military leader under Narses, was declared a king of Heruli in Trentino in northern Italy, but he was executed by Narses. Sinduald was said to be a descendant of the Herules who had already entered Italy under Odoacer.[86][87]

Paul the Deacon writes that many Heruli joined the Lombard king Alboin in their eventual conquest of Italy from the empire in the late 6th century AD.[88]

Along with the Rugii and Sciri, the Heruli may have contributed to the formation of the Bavarii.[89]

Culture

Religion

The early religion of the Heruli is vividly described by Procopius in his History of the Wars. He describes them as a polytheistic society known to practice human sacrifice.[90][91] The Heruli appear to have been worshippers of Odin, and might have been responsible for the spread of such worship to Northern Europe.[92]

By the time of Justinian, Procopius reports that many Heruli had become Arian Christians. In any case, Justinian appears to have pursued a policy of attempting to convert them to Chalcedonian Christianity.[76]

Society

Procopius writes that the Heruli practiced a form of senicide, having a non-relative kill the sick and elderly and burning the remains on a wooden pyre.[90][91] Procopius also states that, following the death of their husbands, Herulian women were expected to commit suicide by hanging.[93][91]

Furthermore, Procopius claims that the Heruli practiced homosexuality[94] or bestiality, depending on the interpretation:

They are still, however, faithless toward them [the Romans], and since they are given to avarice, they are eager to do violence to their neighbours, feeling no shame at such conduct. And they mate in an unholy manner, especially men with asses, and they are the basest of all men and utterly abandoned rascals.[91]

The translated "especially men with asses" is from the original Greek text (provided next to Dewing's translation) "ἂλλας τε καί ἀνδρῶν καί ὄνων"[91] where ὄνων is genitive plural of ὄνος, meaning donkeys.

It appears that Procopius disliked the Heruli and wanted to present them in as negative light as possible. His description of bestiality among the Heruli is almost certainly untrue.[94]

Warfare

The Heruli were famous for the quality of their infantry, who were recruited as mercenaries by all other peoples.[95] They were known particularly for their speed, and were perhaps used for the stabbing cavalry.[96] Procopius described the Heruli in the Battle of Anglon against Persians, carrying no protective armor save a shield and thick jacket.[97][93][98] This form of warfare has been compared to that of the berserkers of the Viking Age.[99]

Herulian slaves are known to have accompanied them into combat. Slaves were forbidden from donning a shield until having proven themselves brave on the battlefield. This practice might be a relic of ancient Indo-European tradition.[94] Steinacher has pointed out that, while this remark has reasonably been seen as evidence of an "initiation rite", initiation rites are so common that caution is required:

It is of course far from clear exactly what Procopius had in mind when writing about Herul 'slaves'. But he surely provided plenty of evidence that any gens was open to newcomers. As in any other human community, both in the past and in the present, such newcomers had to prove themselves worthy before receiving full membership in that community. This must have been even truer for a community geared towards warfare.[100]

Material culture

The tumuli of the Heruli on the Middle Danube in the early 6th century are very similar to contemporary tumuli built in southern Sweden.[101] At this time, the Heruli appears to have had close trade relations with peoples living near the Baltic Sea.[101]

Physical appearance

In Getica, Jordanes writes that the Heruli claimed to be the tallest people of Scandza. Jordanes further writes that all the peoples of Scandza "surpassed the Germans in size and spirit".[30] Sidonius Apollinaris wrote that the Heruli had blue-grey eyes.[102]

The negative excursus of Procopius

Scholars remark that the historian Procopius had a notable fascination with the Herules, which colors his descriptions of them. As Steinacher remarks

"Procopius's Herul excursus [...] is full of stereotypes and negative attitudes towards this primitive people and its archaic conventions".[103]

This means that caution is required when using his descriptions as evidence. In the words of Walter Goffart:

Though appreciative of their military qualities, he goes out of his way to blacken their character - "they are the basest of all men and utterly abandoned rascals," "no men in the world are less bound by convention or more unstable." His low opinion may result from the "special relationship" the Herules appear to have had with Justinian's eunuch general, Narses, who Procopius disliked.[104]

Although Procopius praised the Herule named Pharas who brought about the surrender of the north African Vandal king Gelimer, he noted that despite being born a Herule, he did not drink excessively and was not unreliable.[105]

Procopius was not mollified. The Herules were part of the panorama of an entire "West" that, owing to Justinian's neglect, had come into the possession of the barbarians by the late 540s. [...] The crowning irony, in the historian's view, was that, because some Herules served as Roman foederati, they both plundered Roman subjects and collected pay from the Roman emperor.[106]

Places sacked by the Heruli

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 388.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 322.

- ↑ Neumann 1999, p. 468.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 359–360.

- 1 2 Heather 2007, p. 469. "Heruli – Germanic-speaking group originally from north central Europe, some of whom migrated to regions north of the Black Sea in company with Goths and others in the 3rd century."

- ↑ Taylor 1999, pp. 468–469.

- ↑ Maenchen-Helfen 1947, pp. 837–838. "Schönfeld... offers Germanic etymologies not only for Faras and Alvith but also for Fanotheus, Filimuth, Hariso, Sindval, Svartva, Uligangus, and Visandus. Other Germanic names of the Heruli, not listed in Schönfeld, are Sindila, Batemodus, and Cunthia. Like the Heruli the Rugi were... most certainly a Germanic tribe... The Heruli and Rugians were Germans. So were the Scirians as proved by the names of their leaders."

- ↑ Goffart 2006, pp. 335.

- ↑ Taylor 1999, pp. 468–469: "Aufschluß über die Sprache der H. geben nur die Namen, von denen die lat. und griech. Qu. eindeutig berichten, daß sie von H.n geführt wurden. Diejenigen, die problemlos etymologisierbar sind, lassen sich im Hinblick auf diagnostische Dialektmerkmale nicht von got. Namen derselben Zeit unterscheiden. Dies kann jedoch auf einer sekundären Gotisierung in S-Europa sowie auf lat. und griech. Schreibgewohnheiten beruhen und braucht eine skand. Herkunft nicht auszuschließen."

- ↑ Reynolds & Lopez 1946, p. 42: "It may be granted that the Heruls apparently were Germanic despite the fact that most of the personal names of their leaders baffle German philologist"; " We find among the Heruls an Ochus, which appears Iranian; an Aordus which appears to be based on the name of the Sarmatian Aorsi; and even a Verus, which is quite Roman. Names which "sound" perhaps Dacian were Andonnoballus, Datius, Faras, Alvith, for which neither Forstemann nor Schoenfeld offers a Germanic etymology or can offer one only on the supposition that Greek sources misspelled the name. Only Halaricus, Rodvulf, and Fulcaris yield results to Germanic etymology"

- ↑ Murdoch & Read 2004, p. 5. "The Germani may be split into groups in a variety of ways. Tacitus speaks of Ingaevones, Herminones and Istaevones, which philologists have tried to associate with tribal and linguistic subdivisions. Other distinctions, based on the supposed geographical origins of various tribal groups, divided them into Nordgermanen (who would develop into the various Scandinavian peoples) and Oder-Weichsel-Germanen (those originating around the Oder and the Vistula, and including Goths and a number of tribes with un-or only scantily recorded languages, such as the Burgundians, Herulians, Rugians, Vandals and Gepids). The languages of these two broad groups are usually referred to as North and East Germanic, and are linked more closely with each other than with the third, West Germanic group, made up of Elbgermanen (Lombards, Bavarians and Alemanni or Alemans — again the spelling varies), Nordseegermanen (Angles, Frisians, Saxons) and Weser- Rhein-Germanen (Saxons and Franks)."

- ↑ Murdoch & Read 2004, p. 149. "Gothic is associated with other so-called East Germanic languages spoken by tribes such as the Burgundians, the Vandals and the Gepids (classical historians group them with the Goths), the Herulians, and the Rugians."

- ↑ Kaliff & Munkhammar 2011, p. 12. "East Germanic languages (those of the Burgundians, Gepids, Heruli, Rugians, Sciri and Vandals)."

- ↑ Taylor 1999, p. 469.

- ↑ Angelov 2018, p. 678.

- ↑ Zahariade 2010.

- ↑ Reynolds & Lopez 1946, p. 43 n22: "the term, of course, had no classificatory significance".

- ↑ See for example Wolfram (2005, p. 77) and Steinacher (2017, p. 28).

- ↑ Goffart (2006, pp. 205–206, 335) and Zahariade (2010, p. 167)

- ↑ Wolfram 2005, p. 259.

- ↑ Wolfram 1990, p. 592. "Heruli, Germanic tr."

- 1 2 Heather 1994, p. 87. "[S]ome of the territory covered by the Sîntana de Mureş–Černjachov culture may have been controlled not by Goths but by related Germanic peoples, such as the Heruli."

- ↑ Heather 2012, p. 678. "Heruli, a Germanic people...

- 1 2 Angelov 2018, p. 715. "Heruli. Germanic tribe with possible origins in Scandinavia...

- ↑ Green 2003, p. 13. "Goths and other East Germanic tribes attracted to this region (including Heruli, Burgundians, Vandals and Gepids)."

- ↑ Neumann 1999, p. 468. "[D]ieses ostgerm. Ethnos..."

- ↑ Green 2000, p. 131. "[T]he Heruli who in the course of their migrations sent a party back to Scandinavia for a king from amongst the members of their royal family who had remained behind."

- ↑ Speidel 2004, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Ellegård 1987.

- 1 2 Jordanes 1908, p. III (23).

- 1 2 3 Goffart 2006, pp. 205–209.

- 1 2 Steinacher 2017, pp. 148–152.

- 1 2 3 Procopius 1914, Book VI, XV

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 116.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 124.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 55–66.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 322–327.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 324.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 62.

- ↑ Also see Zahariade (2010).

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 63–65.

- 1 2 Steinacher 2010, pp. 326–327.

- 1 2 Green 2000, p. 1.

- 1 2 Green 2000, p. 137.

- ↑ Heather 1994, p. 87.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 331–333.

- 1 2 Jordanes 1908, p. XXIII (116).

- ↑ Heather 1994, p. 33.

- 1 2 Goffart 2006, p. 206.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 328.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 67.

- ↑ Halsall 2007, p. 260.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 69–73.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 74.

- ↑ Letters 8.9

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 330.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 329.

- ↑ Goffart 2006, Ch.5.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 208.

- 1 2 Steinacher 2010, p. 340.

- 1 2 Heather 2010, p. 242.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 341.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 338-345.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 347.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 251.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 366.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 430.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 144.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 350.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 369.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 350–351.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 351–352.

- 1 2 Sarantis 2010, p. 372.

- 1 2 Goffart 2006, p. 209.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 147.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 225.

- 1 2 Steinacher 2010, pp. 354–355.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, pp. 393–397.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 394.

- ↑ Heather 1998, p. 109.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 385.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 402.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 355.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 159.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 240.

- ↑ Green 2000, p. 321.

- 1 2 Davidson 1990, p. 54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Procopius 1914, Book VI, XIV

- ↑ Davidson 1990, p. 148.

- 1 2 Davidson 1990, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Bremmer 1992, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Jordanes 1908, p. XXIII (117-118).

- ↑ Speidel 2004, p. 136.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 353.

- ↑ Procopius 1914, Book II, XXV

- ↑ Speidel 2004, pp. 58–61.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 360.

- 1 2 Christie 1995, p. 29.

- ↑ Heather 2007, p. 423.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 349.

- ↑ Goffart (2006, pp. 206–207)

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 168.

- ↑ Goffart (2006, p. 208)

Sources

Ancient sources

- Jordanes (1908). The Origins and Deeds of the Goths. Translated by Mierow, Charles C. Princeton University Press.

- Procopius (1914). History of the Wars. Translated by Dewing, Henry Bronson. Heinemann.

Modern sources

- Angelov, Alexander (2018). "Heruli". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 678. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 9780191744457. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Bremmer, Jan (1992). "A Enigmatic Indo-European Rite: Paederasty". Homosexuality in the Ancient World. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815305460.

- Christensen, Arne Søby (2002). Cassiodorus, Jordanes and the History of the Goths. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788772897103.

- Christie, Neil (1995). The Lombards. Wiley. ISBN 0631182381.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1990). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141941509.

- Drout, M. D. C.; Goering, N. (2020). "The Emendation Eorle (Heruli) in Beowulf, Line 6a: Setting the Poem in 'The Named Lands of the North'". Modern Philology. 117 (3): 285–300. doi:10.1086/707097. S2CID 214550424.

- Ellegård, Alvar (1987). "Who were the Eruli?". Scandia. 53.

- Goffart, Walter (2006). Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812239393.

- Green, D. H. (2000). Language and history in the early Germanic world. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521794234.

- Green, Dennis H. (2003). "Linguistic Evidence For The Early Migrations Of The Goths". In Heather, Peter (ed.). The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 11–40. ISBN 9781843830337.

- Green, D. H. (2014). "The Boii, Bohemia, Bavaria". In Fries-Knoblach, Janine; Steuer, Heiko; Hines, John (eds.). The Baiuvarii and Thuringi: An Ethnographic Perspective. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 11–22. ISBN 9781843839156.

- Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107393325.

- Heather, Peter (1998), "Disappearing and reappearing tribes", in Pohl, Walter; Reimitz, Helmut (eds.), Strategies of Distinction: The Construction of the Ethnic Communities, 300-800, ISBN 9004108467

- Heather, Peter (1994). Goths and Romans 332–489. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198205357.001.0001. ISBN 9780198205357.

- Heather, Peter (2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195325416.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199892266.

- Heather, Peter (2012). "Heruli". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 715. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Kaliff, Anders; Munkhammar, Lars (2011). Wulfila 311-2011 (PDF). Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 9789155486648. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2020.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (July 1947). "Communications". The American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 52 (4): 836–841. JSTOR 1842348.

- Murdoch, Brian; Read, Malcolm Kevin (2004). Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 157113199X.

- Neumann, Günter [in German] (1999). "Heruler: § 1. Philologisches". Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 14. Walter de Gruyter. p. 468. ISBN 9783110164237.

- Reynolds, Robert L.; Lopez, Robert S. (October 1946). "Odoacer: German or Hun?". The American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 52 (1): 36–53. doi:10.2307/1845067. JSTOR 1845067.

- Sarantis, Alexander (2010). "The Justinianic Herules". In Curta, Florin (ed.). Neglected Barbarians. ISD. ISBN 9782503531250.

- Speidel, Michael P. (2004). Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior Styles from Trajan's Column to Icelandic Sagas. Routledge. ISBN 1134384203.

- Steinacher, Roland [in German] (2010). "The Herules: Fragments of a History". In Curta, Florin (ed.). Neglected Barbarians. ISD. ISBN 9782503531250.

- Steinacher, Roland (2017), Rom und die Barbaren. Völker im Alpen- und Donauraum (300-600), ISBN 9783170251700

- Taylor, Marvin Hunter (1990). "The Etymology of the Germanic Tribal Name Eruli". General Linguistics. 30 (2): 108–125.

- Taylor, Marvin Hunter (1999). "Heruler". Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 14. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 468–473. ISBN 9783110164237.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1990). History of the Goths. Translated by Dunlap, Thomas J. University of California Press. ISBN 0520069838.

- Wolfram, Herwig (2005). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520244900.

- Zahariade, Mihail (2010), "A Crux in Bellum Scythicum. The Invasion of 267: Gothi or Heruli?", Antiquitas istro-pontica : Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire ancienneofferts à Alexandru Suceveanu

External links

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Troels Brandt: The Heruls in Scandinavia Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Machine