| Valerian | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

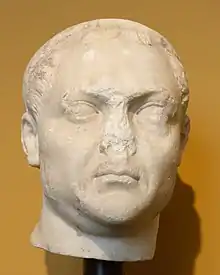

Bust of Valerian | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | September 253 – June 260 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Aemilian | ||||||||

| Successor | Gallienus (alone) | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Gallienus | ||||||||

| Born | c. 199[1] | ||||||||

| Died | After 260 or 264 AD Bishapur or Gundishapur | ||||||||

| Spouses |

| ||||||||

| Issue Detail | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Valerian | ||||||||

Valerian (/vəˈlɪəriən/, və-LEER-ee-ən; Latin: Publius Licinius Valerianus; c. 199 – 260 or 264) was Roman emperor from 253 to spring 260 AD. Valerian is known as the first Roman emperor to have been taken captive in battle, captured by the Persian emperor Shapur I after the Battle of Edessa, causing shock and instability throughout the Roman Empire. The unprecedented event and the unknown fate of the captured emperor generated a variety of different reactions and "new narratives about the Roman Empire in diverse contexts".[3]

Biography

Origins and rise to power

Unlike many of the would-be emperors and rebels who vied for imperial power during the Crisis of the Third Century, Valerian was of a noble and traditional senatorial family. Details of his early life are sparse, except for his marriage to Egnatia Mariniana, with whom he had two sons: Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (his co-emperor and later successor) and Licinius Valerianus.[4]

Valerian was consul for the first time either before AD 238 as a Suffectus or in 238 as an Ordinarius. In 238 he was princeps senatus, and Gordian I negotiated through him for senatorial acknowledgement for his claim as emperor. In 251 AD, when Decius revived the censorship with legislative and executive powers so extensive that it practically embraced the civil authority of the emperor, Valerian was chosen censor by the Senate,[5] though he declined to accept the post. During the reign of Decius he was left in charge of affairs in Rome when that prince left for his ill-fated last campaign in Illyricum.[6] Under Trebonianus Gallus Valerian was appointed dux of an army probably drawn from the garrisons of the German provinces which seems to have been ultimately intended for use in a war against the Persians.[7]

However, when Trebonianus Gallus had to deal with the rebellion of Aemilianus in 253 AD, he turned to Valerian for assistance in crushing the attempted usurpation. Valerian headed south but was too late: Gallus was killed by his own troops, who joined Aemilianus before Valerian arrived. The Raetian soldiers then proclaimed Valerian emperor and continued their march towards Rome. Upon his arrival in September, Aemilianus's legions defected, killing Aemilianus and proclaiming Valerian emperor. In Rome, the Senate quickly acknowledged Valerian.[8]

_obverse.jpg.webp)

Rule and fall

Valerian's first act as emperor was to appoint his son Gallienus augustus, thus making him co-emperor. Early in his reign, affairs in Europe went from bad to worse, and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Sassanid vassal and Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor).[5] Valerian and Gallienus split the problems of the empire between them, with the son taking the West, and the father heading East to face the Persian threat.

In 254, 255, and 257, Valerian again became Consul Ordinarius. By 257, he had recovered Antioch and returned the province of Syria to Roman control. The following year, the Goths ravaged Asia Minor. In 259, Valerian moved on to Edessa, but an outbreak of plague killed a critical number of legionaries, weakening the Roman position, and the town was besieged by the Persians. In 260, probably in June,[8] Valerian was decisively defeated in the Battle of Edessa and held prisoner for the remainder of his life. Valerian's capture was a tremendous defeat for the Romans.[12]

Persecution of Christians

While fighting the Persians, Valerian sent two letters to the Senate ordering that firm steps be taken against Christians. The first, sent in 257, commanded Christian clergy to perform sacrifices to the Roman gods or face banishment. The second, the following year, ordered the execution of Christian leaders. It also required Christian senators and equites to perform acts of worship to the Roman gods or lose their titles and property, and directed that they be executed if they continued to refuse. It also decreed that Roman matrons who would not apostatize should lose their property and be banished, and that civil servants and members of the Imperial household who would not worship the Roman gods should be reduced to slavery and sent to work on the Imperial estates.[13] This indicates that Christians were well-established at that time, some in very high positions.[14]

The execution of Saint Prudent at Narbonne is taken to have occurred in 257.[15] Prominent Christians executed in 258 included Pope Sixtus II (6 August), Saint Romanus Ostiarius (9 August) and Saint Lawrence (10 August). Others executed in 258 included the saints Denis in Paris, Pontius in Cimiez, Cyprian and others in Carthage and Eugenia in Rome. In 259 Saint Patroclus was executed at Troyes and Saint Fructuosus at Tarragona.[15] When Valerian's son Gallienus became emperor in 260, the decree was rescinded.[14]

Death in captivity

Eutropius, writing between 364 and 378 AD, stated that Valerian "was overthrown by Shapur king of Persia, and being soon after made prisoner, grew old in ignominious slavery among the Parthians."[16] An early Christian source, Lactantius (thought to be virulently anti-Persian, thanks to the occasional persecution of Christians by some Sasanian monarchs)[17] maintained that, for some time prior to his death, Valerian was subjected to the greatest insults by his captors. For example, being used as a human footstool by Shapur when mounting his horse. According to this version of events, after a long period of such treatment, Valerian offered Shapur a huge ransom for his release.[5]

In reply (according to one version), Shapur was said to have forced Valerian to swallow molten gold (the other version of his death is almost the same but it says that Valerian was killed by being flayed alive) and then had Valerian skinned and his skin stuffed with straw and preserved as a trophy in the main Persian temple.[5] It was further alleged that it was only after a later Persian defeat against Rome that his skin was given a cremation and burial.[18] The captivity and death of Valerian has been frequently debated by historians without any definitive conclusion.[17]

According to the modern scholar Touraj Daryaee,[17] contrary to the account of Lactantius, Shapur I sent Valerian and some of his army to the city of Bishapur or Gundishapur where they lived in relatively good conditions. Shapur used the remaining soldiers in engineering and development plans. Band-e Kaisar (Caesar's dam) is one of the remnants of Roman engineering located near the ancient city of Susa.[19] In all the stone carvings on Naghshe-Rostam, in Iran, Valerian is represented holding hands with Shapur I, a sign of submission. According to the early Persian Muslim scholar Abu Hanifa Dinawari, Shapur settled the prisoners of war in Gundishapur and released Valerian, as promised, after the construction of Band-e Kaisar.[20]

It has been alleged that the account of Lactantius is coloured by his desire to establish that persecutors of the Christians died fitting deaths;[21] the story was repeated then and later by authors in the Roman Near East fiercely hostile to Persia.[22]

The joint rule of Valerian and Gallienus was threatened several times by usurpers. Nevertheless, Gallienus held the throne until his own assassination in 268 AD.[23]

Family

- Gallienus

- Licinius Valerianus was another son of Valerian I. Consul in 265, he was probably killed by usurpers, some time between the capture of his father in 260 and the assassination of his brother Gallienus in 268.

| Aulus Egnatius Priscillianus philosopher | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quintus Egnatius Proculus consul suffectus | Lucius Egnatius Victor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Egnatius Victor Marinianus consul suffectus | 1.Mariniana | Valerian Emperor 253-260 | 2.Cornelia Gallonia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| previous Aemilianus Emperor 253 | (1) Gallienus Emperor 253-268 ∞ Cornelia Salonina | (2) Licinius Valerianus consul suffectus | Claudius Gothicus Emperor 268-270 | Quintillus co-emperor 270 | Aurelian Emperor 270-275 ∞ Ulpia Severina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valerian II caesar | Saloninus co-emperor | Publius Licinius Egnatius Marinianus consul 268 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In popular culture

- Valerian appears in Harry Sidebottom's historical fiction series of novels Warrior of Rome.

- He also appears in Anthony Hecht's poem "Behold the Lilies of the Field" in the collection The Hard Hours.

- He is referenced in Evelyn Waugh's Helena: "Do you know what has happened to the Immortal Valerian?...They have him on show in Persia, stuffed."

- The character Valerian Street in Toni Morrison’s novel Tar Baby is named after the emperor.

- Valerian appears in Joseph of Anchieta’s play Auto de São Lourenço as one of the main characters. In Act III, Valerian is killed for being responsible for the persecution and killing of Saint Lawrence, in the year 258 AD.

See also

- Gallienus usurpers for all the usurpers of Valerian and Gallienus' reigns.

- Valeriana, a genus of plants named for the emperor.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Valerianus, Publius Licinius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 859.

- ↑ RE 13.1 (1926) col. 488, Licinius 173. John Malalas 12.298 gives his age at death as 61 years, but apparently mistakes the emperor for his identically-named son. Weigel says he was born shortly before 200.

- ↑ Valerian's full title at his death was Imperator Caesar Pvblivs Licinivs Valerianvs Pivs Felix Invictvs Avgvstvs Germanicvs Maximvs Pontifex Maximvs Tribuniciae Potestatis VII Imperator I Consul IV Pater Patriae, "Emperor Caesar Publius Licinius Valerianus, Patriotic, Favored, Unconquered Augustus, Conqueror of the Germans, Chief Priest, seven times Tribune, once Emperor, four times Consul, Father of the Fatherland".

- ↑ Caldwell, Craig H. (2018). "The Roman Emperor as Persian Prisoner of War: Remembering Shapur's Capture of Valerian". Brill's Companion to Military Defeat in Ancient Mediterranean Society. pp. 335–358. doi:10.1163/9789004355774_016. ISBN 9789004355774.

- ↑ Bray, J. (1997). Gallienus: A study in reformist and sexual politics. Kent Town, S. Australia: Wakefield Press. p. 20. ISBN 1-86254-337-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Zonaras. Epitome Historiarum. p. XII, 20.

- ↑ Christol, Michel (1980). "A propos de la politique exterieure de Trebonien Galle". Revue Numismatique. 22 (6): 63–74. doi:10.3406/numi.1980.1803.

- 1 2 Peachin, Michael (1990). Roman Imperial Titulature and Chronology, A.D. 235–284. Amsterdam: Gieben. pp. 36–38. ISBN 90-5063-034-0.

- ↑ Overlaet, Bruno (2017). "ŠĀPUR I: ROCK RELIEFS". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

The two emperors who are named are shown in the way they are described: Philip the Arab is kneeling, asking for peace, and Valerian is physically taken prisoner by Šāpur. Consequently, the relief must have been made after 260 CE.

- ↑ Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 274. ISBN 978-1610693912.

(...) while another figure, probably Philip the Arab, kneels, and the Sasanian king holds the ill-fated Emperor Valerian by his wrist.

- ↑ Corcoran, Simon (2006). "Before Constantine". In Lenski, Noel (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0521521574.

He recorded these deeds for posterity in both words and images at Naqsh-i Rustam and on the Ka'aba-i Zardušt near the ancient Achaemenid capital of Persepolis, preserving for us a vivid image of two Roman emperors, one kneeling (probably Philip the Arab, also defeated by Shapur) and the second (Valerian), uncrowned and held captive at the wrist by a gloriously mounted Persian king.

- ↑ Valerian

- ↑ W. H. C. Frend (1984). The Rise of Christianity. Fortress Press, Philadelphia. p. 326. ISBN 978-0800619312.

- 1 2 Moss 2013, p. 153.

- 1 2 Baudoin 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ Eutropius. Abridgement of Roman History. Translated by the Rev. John Selby Watson. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853. (Book 9.7)

- 1 2 3 Daryaee, Touraj (2008). Sasanian Iran. Mazda. ISBN 978-1-56859-169-8.

- ↑ Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum, v; Wickert, L., "Licinius (Egnatius) 84" in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie 13.1 (1926), 488–495; Parker, H., A History of the Roman World A.D. 138 to 337 (London, 1958), 170. From .

- ↑ Abdolhossein Zarinkoob "Ruzgaran: tarikh-i Iran az aghz ta saqut saltnat Pahlvi" pp. 195

- ↑ Abū Ḥanīfah Aḥmad ibn Dāvud Dīnavarī; Mahdavī Dāmghānī, Maḥmūd (2002). Akhbār al-ṭivāl (5th ed.). Tihrān: Nashr-i Nay. p. 73. ISBN 9789643120009. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Meijer, Fik (2004). Emperors don't die in bed. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31202-7.

- ↑ Isaacs, Benjamin (1997). The Near East under Roman Rule. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 440. ISBN 90-04-09989-1.

- ↑ Saunders, Randall T. (11 January 1992). "Who Murdered Gallienus?". Antichthon. 26: 80–94. doi:10.1017/S0066477400000708. ISSN 0066-4774. S2CID 146694960.

Sources

Primary sources

Secondary sources

- Baudoin, Jacques (2006), "Saint Prudent", Grand livre des saints: culte et iconographie en Occident (in French), EDITIONS CREER, ISBN 978-2-84819-041-9, retrieved 20 December 2017

- Moss, Candida (2013), The Myth of Persecution, HarperCollins, p. 153, ISBN 978-0-06-210452-6

External links

- "Valerian and Gallienus", at De Imperatoribus Romanis.