| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| History of religions |

|---|

The history of Christianity follows the Christian religion from the first century to the twenty-first as it developed from its earliest beliefs and practices, spread geographically, and changed into its contemporary global forms.

Christianity originated with the ministry of Jesus, a Jewish teacher and healer who proclaimed the imminent Kingdom of God and was crucified c. AD 30–33 in Jerusalem in the Roman province of Judea. The earliest followers of Jesus were apocalyptic Jewish Christians. Christianity remained a Jewish sect, for centuries in some locations, diverging gradually from Judaism over doctrinal, social and historical differences.

In spite of occasional persecution in the Roman Empire, the religious movement spread as a grassroots movement that became established by the third century both in and outside the empire. The Roman Emperor Constantine I became the first Christian emperor in 313. He issued the Edict of Milan expressing tolerance for all religions thereby legalizing Christian worship. Various Christological debates about the human and divine nature of Jesus occupied the Christian Church for three centuries, and seven ecumenical councils were called to resolve them.

Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization in Europe after the Fall of Rome. In the Early Middle Ages, missionary activities spread Christianity towards the west and the north. During the High Middle Ages, Eastern and Western Christianity grew apart, leading to the East–West Schism of 1054. Growing criticism of the Roman Catholic church and its corruption in the Late Middle Ages led to the Protestant Reformation and its related reform movements, which concluded with the European wars of religion, the return of tolerance as a theological and political option, and the Age of Enlightenment.

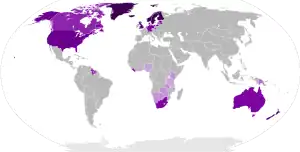

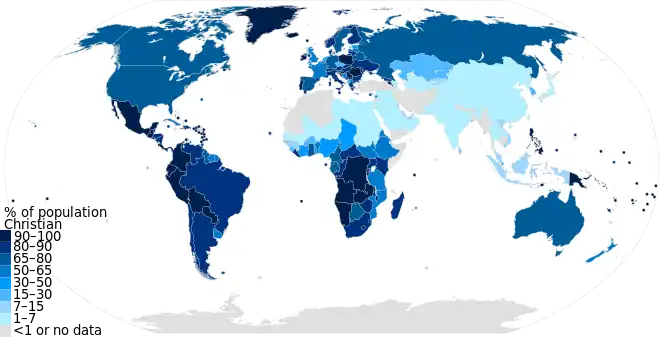

In the twenty-first century, traditional Christianity has declined in the West, while new forms have developed and expanded throughout the world. Today, there are more than two billion Christians worldwide and Christianity has become the world's largest, and most widespread religion.[1][2] Within the last century, the center of growth has shifted from West to East and from the North to the global South.[3][4][5][6]

Origins to 312

Little is fully known of primitive Christianity.[7] Sources on its first 150 years are fragmentary and scarce.[8] This, along with a variety of complications, has limited scholars to conclusions that are probable rather than provable, based largely on the book of Acts, whose historicity is debated as much as it is accepted.[9][note 1]

Beginnings

Christianity began with the itinerant preaching and teaching of a deeply pious young Jewish man, Jesus of Nazareth.[13][14] According to the Gospels, Jesus was the Son of God, who was crucified c. AD 30–33 in Jerusalem.[15] His followers believed that he was raised from the dead and exalted by God, heralding the future Kingdom of God. Theologian and minister Frances M. Young says this is what "lies at the heart of Christianity."[13][15]

Virtually all scholars of antiquity accept that Jesus was a historical figure.[16][note 2] However, in the twenty-first century, tensions surround the figure of Jesus and the supernatural features of the gospels, creating, for many, a distinction between the 'Jesus of history' and the 'Christ of faith'.[27][note 3] Yet, as Young has observed, "it is precisely Christology, the dogmas concerning the divinity and humanity of Christ, which have made Christianity what it is".[29]

It was amongst a small group of Second Temple Jews, looking for an "anointed" leader (messiah or king) from the ancestral line of King David, that Christianity first formed in relative obscurity.[30][15] Led by James the Just, brother of Jesus, they described themselves as "disciples of the Lord" and followers "of the Way".[31][32] According to Acts 9[33] and 11,[34] a settled community of disciples at Antioch were the first to be called "Christians".[35][36][37]

While there is evidence in the New Testament (Acts 10) suggesting the presence of Gentile Christians from the beginning, most early Christians were actively Jewish.[38] Jewish Christianity was influential in the beginning, and it remained so in Palestine, Syria, and Asia Minor into the second and third centuries.[39][40] New Testament professor Joel Marcus explains that Judaism and Christianity eventually diverged over disagreements about Jewish law, Jewish insurrections against Rome which Christians did not support, and the development of Rabbinic Judaism by the Pharisees, the sect which had rejected Jesus from the start.[41]

Geographically, Christianity began in Jerusalem in first-century Judea, a province of the Roman Empire. The religious, social, and political climate of the area was diverse and often characterized by turmoil.[15][42] The Roman Empire had only recently emerged from a long series of civil wars, and would experience two more major periods of civil war over the next centuries.[43] Romans of this era feared civil disorder, giving their highest regard to peace, harmony and order.[44] Piety equaled loyalty to family, class, city and emperor, and it was demonstrated by loyalty to the practices and rituals of the old religious ways.[45]

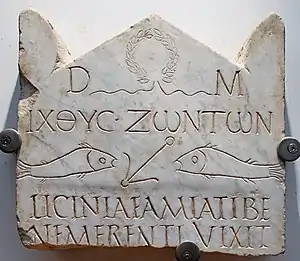

While Christianity was largely tolerated, some also saw it as a threat to "Romanness" which produced localized persecution by mobs and governors.[46][47] In 250, Decius made it a capital offence to refuse to make sacrifices to Roman gods resulting in widespread persecution of Christians.[48][49] Valerian pursued similar policies later that decade. The last and most severe official persecution, the Diocletianic Persecution, took place in 303–311.[50] During these early centuries, Christianity spread into the Jewish diaspora communities, establishing itself beyond the Empire's borders as well as within it.[51][52][53][54][note 4]

Mission in primitive Christianity

_(14769867871).jpg.webp)

From its beginnings, the Christian church has seen itself as having a double mission: first, to fully live out its faith, and second, to pass it on, making Christianity a 'missionary' religion from its inception.[57] Driven by a universalist logic, missions are a multi-cultural, often complex, historical process.[58]

Evangelism began immediately through the twelve Apostles, and the Apostle Paul making multiple trips to found new churches.[59] Christianity quickly spread geographically and numerically, with interaction sometimes producing conflict, and other times producing converts and accommodation.[60][61]

Early geographical spread

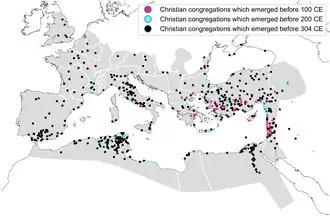

Beginning with less than 1000 people, by the year 100, Christianity had grown to perhaps one hundred small household churches consisting of an average of around seventy (12–200) members each.[63] It achieved critical mass in the hundred years between 150 and 250 when it moved from fewer than 50,000 adherents to over a million.[64] This provided enough adopters for its growth rate to be self-sustaining.[64][65]

It was in Asia Minor, in what Christine Trevett calls the "nurseries" of Christianity - (Athens, Corinth, Ephesus, and Pergamum) - that conflicts over the nature of Christ's divinity first emerged in the second century, and were resolved by referencing apostolic teaching.[66][note 5] In the mid-second century, Christian writers began using "heresy" to describe deviance from that tradition.[73]

There is no archaeological evidence of Christianity in Egypt before the fourth century, though the literary evidence for it is immense.[74][note 6] Egyptian Christianity probably began in the first century in Alexandria.[82][note 7] Egyptian Christians produced religious literature more abundantly than any other region during the second and third centuries.[76] According to Pearson, "By the end of the third century, the Alexandrian church was at least as influential in the east as the Roman church was in the west".[85]

.svg.png.webp)

Christianity in Antioch is mentioned in Paul's epistles written before 60 AD, and scholars generally see Antioch as a primary center of early Christianity.[86][note 8]

Early Christianity was also present in Gaul, however, most of what is known comes from a letter, most likely written by Irenaeus, which theologically interprets the detailed suffering and martyrdom of Christians from Vienne and Lyons during the reign of Marcus Aurelius.[89] There is no other evidence of Christianity in Gaul, beyond one inscription on a gravestone, until the beginning of the fourth century.[90]

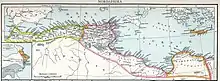

.svg.png.webp)

The origins of Christianity in North Africa are unknown, but most scholars connect it to the Jewish communities of Carthage.[91] Christians were persecuted in Africa intermittently from 180 until 305.[92][note 9] Persecution under Emperors Decius and Valerian created long-lasting problems for the African church when those who had recanted tried to rejoin the Church.[94]

It is likely the Christian message arrived in the city of Rome very early, though it is unknown how or by whom.[95] Tradition, and some evidence, supports Peter as the organizer and founder of the Church in Rome which already existed by 57 AD when Paul arrived there.[96] The city was a melting pot of ideas, and according to Markus Vinzent, the Church in Rome was "fragmented and subject to repeated internal upheavals ... [from] controversies imported by immigrants from around the empire".[97] Walter Bauer's thesis that heretical forms of Christianity were brought into line by a powerful, united, Roman church forcing its will on others is not supportable, writes Vinzent, since such unity and power did not exist before the eighth century.[98][99][100]

Christianity quickly spread beyond the Roman Empire. Armenia, Persia (modern Iran), Ethiopia, Central Asia, India and China have evidence of early Christian communities.[101] Catholic historian Robert Louis Wilken writes of first hand evidence from the sixth century for Christian communities in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Baghdad, Tibet, Georgia, and Socotra an island in the Arabian Sea.[102]

Early beliefs and practices

According to historians Matthews and Platt, "Christianity rose from obscurity and gained much of its power from the tremendous moral force of its central beliefs and values".[14] Early Christianity had a revolutionary understanding of power as service.[103] Based on this reversal of power, and the church's acute concern with volition, Christianity confronted the ancient system where sexual morality was determined by social position.[104][105]

Social status, which Romans saw as given by fate, allowed aristocrats to believe themselves moral even while taking sexual advantage of those below their status level: slaves, wives and mistresses, children and foster children. Christians advocated the radical notion of individual freedom making each person, male and female, slave and free, equally responsible for themselves, to God, regardless of status.[106] It was a turning point in sexual morality, and in the image of the human being, that influenced the next millennia.[107]

Early Christian communities were highly inclusive in terms of social categories, being open to men and women, rich and poor, slave and free, in contrast to traditional Roman social stratification.[108][109] In groups formed by Paul the Apostle, the role of women was greater than in any form of Judaism or paganism at the time.[110][111] There were no fees, and it was intellectually egalitarian, making philosophy and ethics available to ordinary people whom Rome had deemed incapable of ethical reflection.[112][113]

Family had previously determined where and how the dead could be buried, but Christians gathered those not related by blood into a common burial space, used the same memorials, and expanded the audience to include others of their community, thereby redefining the meaning of family.[114][115] Christians distributed bread to the hungry, nurtured the sick, and showed the poor great generosity.[116][117][note 10]

Christianity in its first 300 years was also highly exclusive,[119] as believing was the crucial and defining characteristic that set a "high boundary" that strongly excluded non-believers.[119] In Daniel Praet's view, the exclusivity of Christian monotheism formed an important part of its success, enabling it to maintain its independence in a society that syncretized religion.[120]

Church hierarchy

The church as an institution began its formation quickly and with some flexibility. The New Testament mentions bishops, (Episkopoi), as overseers and presbyters as elders or priests, with deacons as 'servants', sometimes using the terms interchangeably.[121] According to Gerd Theissen, institutionalization began when itinerant preaching transformed into resident leadership (those living in a particular community over which they exercised leadership).[122] A study by Edwin A. Judge, social scientist, shows that a fully organized church system had evolved before Constantine and the Council of Nicaea in 325.[123]

New Testament

In the first century, new texts were written by and for Christians in Koine Greek. These became the "New Testament", and the Hebrew Scriptures became the "Old Testament".[124] Even in the formative period, these texts had considerable authority, and those seen as "scriptural" were generally agreed upon.[125] Linguistics scholar Stanley E. Porter says "the text of [most of] the Greek New Testament was relatively well established and fixed by the time of the second and third centuries".[126]

When discussion of canonization began, there were disputes over whether or not to include some texts.[127][128] The list of accepted books was established by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397.[129] Spanning two millennia, the Bible has become one of the most influential works ever written, having contributed to the formation of Western law, art, literature, literacy and education.[130][131]

Church fathers

The earliest orthodox writers of the first and second centuries, outside the writers of the New Testament itself, were first called the Apostolic Fathers in the sixth century.[132] The title is used by the Church to describe the intellectual and spiritual teachers, leaders and philosophers of early Christianity.[133] Writing from the first century to the close of the eighth, they defended their faith, wrote commentaries and sermons, recorded the Creeds and church history, and lived lives that were exemplars of their faith.[134]

313 – 600

In the fourth and fifth centuries, Rome faced overwhelming problems at all levels of society.[135] Bureaucracy became increasingly incompetent and corrupt,[136] there was rampant inflation,[137] a crushing and inequitable tax system,[138] and significant changes in an army without capable leaders.[139] Barbarians sacked Rome, invaded Britain, France, and Spain, seized land, and disrupted the empire's economy.[140] Matthews and Platt say it is symptomatic that during crises, Roman Senators still collected rent, sometimes doubling the fees, while the Church offered "shelter to the homeless, food for the hungry, and comfort to the grieving".[141] After the political fall of the western Roman Empire in 476 AD, the Christian church became society's unifying influence. Western civilization's center shifted from the Mediterranean basin to the European continent.[142]

Influence of Constantine

The Roman Emperor Constantine the Great became the emperor in the West and the first Christian emperor in 313. He did not become sole emperor until he had defeated Licinius, the emperor in the East in 324.[143] In 313, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, expressing tolerance for all religions, thereby legalizing Christian worship.[143] Christianity did not become the official religion of the empire under Constantine, but the steps he took to support and protect it were vitally important in the history of Christianity.[144]

He established equal footing for Christian clergy by granting them the same immunities pagan priests had long enjoyed.[144] He gave bishops judicial power.[145] By intervening in church disputes, he initiated a precedent.[146][147] He wrote laws that favored Christianity,[148][146] and he personally endowed Christians with gifts of money, land and government positions.[149][150] Instead of rejecting state authority, bishops were grateful, and this change in attitude proved to be critical to the further growth of the Church.[145]

Constantine's church building was influential in the spread of Christianity.[145] He devoted imperial and public funds, endowed his churches with wealth and lands, and provided revenue for their clergy and upkeep.[151] This, writes Cameron, "set a pattern for others, and by the end of the fourth century every self-respecting city, however small, had at least one church".[151]

Regional developments

Christianity between 300 and 600 did not have a central government, as the Bishop of Rome had not yet manifested as the singular leader, allowing Christianity to have some differences in its many separate locations.[98][99][100] Some Germanic people adopted Arian Christianity while others, such as the Goths, adopted catholicism. Having one religion aided their unification into the distinct groups that became the future nations of Europe.[152][153] A "seismic moment" in Christian history took place in 612 when the Visigothic King Sisebut declared the obligatory conversion of all Jews in Spain, overriding Pope Gregory who had reiterated the traditional ban against forced conversion of the Jews in 591.[154] Armenia adopted Christianity in this period, making it their state religion,[155] as did Georgia, Ethiopia and Eritrea.[156][157][158]

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 had little direct impact on the Eastern Roman Empire. With an "autocratic government, stable farm economy, Greek intellectual heritage and ... Orthodox Christianity", it had great wealth and varied resources enabling it to survive until 1453.[159] In the sixth century, East influenced West when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I attempted to reunite empire by taking over both territory and the Church. From the 600s to the 700s, Roman Popes had to be approved by the Eastern emperor before they could be installed, requiring consistency with Eastern policy including the requirement that pagans convert. This had not previously been a requirement in the West.[160][161]

First ecumenical councils

During Antiquity, the Eastern Church produced multiple doctrinal controversies that the orthodox called heresies, and ecumenical councils were convened to resolve these often heated disagreements.[162] The first was between Arianism, which said the divine nature of Jesus was not equal to the Father's, and orthodox trinitarianism which says they are equal. Arianism spread throughout most of the Roman Empire from the fourth century onwards.[163] The First Council of Nicaea (325) and the First Council of Constantinople (381) resulted in a condemnation of Arian teachings and produced the Nicene Creed.[163][164]

The Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth ecumenical councils are characterized by attempts to explain Jesus' human and divine natures.[165] One such attempt created the Nestorian controversy, then schism, then a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Assyrian, and Egyptian churches. This resulted in what is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy, one of three major branches of Eastern Christianity these controversies produced, along with the Church of the East in Persia and Eastern Orthodoxy in Byzantium.[166][167][168]

Late Roman Christian culture

Late Roman culture was a synthesis of the Christian and Greco-Roman.[169] Christian intellectuals adapted Greek philosophy and Roman traditions to Christian use, took from Rome the class structure of aristocratic landowners and dependent laborers, and saw the Church emerge as a state within the State.[169]

Substantial growth in the third and fourth centuries had made Christianity the majority religion by the mid-fourth century, and after Constantine until the Fall of Empire, all emperors were Christian except Julian. Christian Emperors wanted the empire to become a Christian empire.[170][171]

Whether or not the Roman Empire of this period officially made Christianity its state religion continues to be debated. According to Bart Ehrman biblical scholar, "Constantine did not make Christianity the one official and viable religion".[172] In a study of Roman Law, historian Michele Renee Salzman found no legislation forcing conversion of pagans until the Eastern emperor Justinian in A.D. 529.[161][note 11]

Triumph and pagans

Even though Christians only made up around ten percent of the Roman population in 313, they spread a belief they universally held: that Constantine's conversion was evidence the Christian God had conquered the pagan gods in Heaven.[187][188][189] This "triumph of Christianity" became the primary narrative of the late antique age.[190][191] Historian Peter Brown surmises that, outside of political disagreements, this made it generally unnecessary and even undesirable to mistreat polytheists.[192][193][194]

Following what Salzman calls "a carrot and stick" policy, Christian emperors wrote laws offering incentives for supporting Christianity and laws that negatively impacted those who did not.[195] Constantine never outlawed paganism, but consensus is that he did write the first laws prohibiting sacrifice which, thereafter, largely disappeared by the mid fourth century.[196][197][198][note 12] Eusebius also attributes to Constantine widespread temple destruction, however, while the destruction of temples is in 43 written sources, only four have been confirmed archaeologically.[200][note 13]

What is known with some certainty is that Constantine was vigorous in reclaiming confiscated properties for the Church, and he used reclamation to justify the destruction of some pagan temples such as Aphrodite's temple in Jerusalem. For the most part, Constantine simply neglected them.[205][206][207][note 14] With the exception of a few temples, it was the eighth century when temples in Rome began being converted into churches.[215]

Relations with Jews

In the fourth century, Augustine argued against persecution of the Jewish people. According to Anna Sapir Abulafia, Jews and Christians in Latin Christendom lived in relative peace until the thirteenth century,[216][217] although anti-Semitic violence erupted occasionally. Attacks on Jews by mobs, local leaders and lower level clergy were carried out without the support of church leaders who generally followed Augustine's teachings.[218][219]

Sometime before the fifth century, the theology of supersessionism emerged, claiming that Christianity had displaced Judaism as God's chosen people.[220] Supersessionism was not an official or universally held doctrine, but replacement theology has been part of Christian thought through much of history.[221][222] Many attribute antisemitism to this doctrine while others make a distinction between supersessionism and modern anti-Semitism.[223][224]

Monasticism and public hospitals

Christian monasticism emerged in the third century, and by the fifth century, was a dominant force in all areas of late antique culture.[225][note 15] Monastics developed a health care system which allowed the sick to remain within the monastery as a special class afforded special benefits and care.[231] This destigmatized illness and formed the basis for future public health care. The first public hospital (the Basiliad) was founded by Basil the Great in 369.[232]

Basil was the central figure in the development of monasticism in the East. In the West, it was Benedict, who created the Rule of Saint Benedict, which would become the most common rule throughout the Middle Ages and the starting point for other monastic rules.[233]

600 – 1100

This era is most characterized by the uniting of classical Graeco-Roman thinking, Germanic culture and Christian ethos into a new civilization centered in Europe.[234][235]

After the fall of Rome, the Church provided what little security there was.[236] Even after Justinian, there were still no populations that were fully converted to Christianity.[237] Within this uncertain environment, the Church was like an early version of a welfare state sponsoring public hospitals, orphanages, hospices, and hostels (inns). The ever increasing number of monasteries and convents supplied food for all during famine and regularly distributed food to the poor.[236][238][239]

Monasteries actively preserved ancient texts, classical craft and artistic skills, while maintaining an intellectual culture, and supporting literacy, within their schools, scriptoria and libraries.[240][241] They were models of productivity and economic resourcefulness, teaching their local communities animal husbandry, cheese making, wine making, and various other skills.[242] Medical practice was highly important and medieval monasteries are best known for their contributions to medical tradition. They also made advances in sciences such as astronomy, and St. Benedict's Rule (480–543) impacted politics and law.[239][243] The formation of these organized bodies of believers gradually carved out a series of social spaces with some amount of independence, distinct from political and familial authority, thereby revolutionizing social history.[244]

Western expansion

The conversion of the Irish is "one of the defining aspects of the early medieval period" writes archaeologist Lorcan Harney.[245] Christianization in Ireland was diverse, embraced syncretization with prior beliefs, and was not the result of force.[246] Archaeology indicates Christianity had become an established minority faith in some parts of Britain before Irish missionaries went to Iona (from 563) and converted many Picts.[247][248] The Gregorian mission landed in 596, and converted the Kingdom of Kent and the court of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria.[249]

The Frankish King Clovis I was the first to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler. He then converted to Roman Catholicism around 498-508.[250][251] Clovis' descendent Charlemagne began the Carolingian Renaissance, sometimes called a Christian renaissance, a period of intellectual and cultural revival of literature, arts, and scriptural studies, a renovation of law and the courts, and the promotion of literacy.[252][note 16]

Rise of universities

Modern western universities have their origins directly in the Medieval Church.[261][262][263] The earliest were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Oxford (1096), and the University of Paris where the faculty was of international renown (c. 1150).[264][265] Matthews and Platt say "these were the first Western schools of higher education since the sixth century".[266] They began as cathedral schools, then formed into self-governing corporations with charters.[266] Divided into faculties which specialized in law, medicine, theology or liberal arts, each held quodlibeta (free-for-all) theological debates amongst faculty and students, and awarded degrees.[266][267]

Eastern Christianities (604–1071)

By the time of Justinian I (527–565), Constantinople was the largest, most prosperous and powerful city in the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[268] By the end of the first millennium, a rich and varied culture, characterized by ethnic diversity, had fully developed in the East centered around its greatest city. Constantinople had become famous for its prosperity and power, its numerous market places, massive walls, magnificent monuments, and the religious devotion of its inhabitants, which was thought to have won it the blessing and protection of God.[269][270]

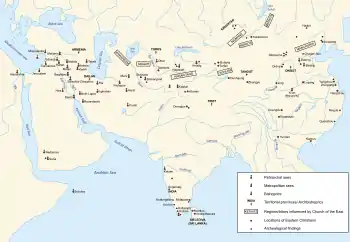

In the same period, the Church of the East within the Persian/Sasanian Empire had spread over modern Iraq, Iran, and parts of Central Asia.[271] The shattering of the Sassanian Empire in the early 600s led upper-class refugees to move further east to China, entering Hsian-fu in 635.[272]

In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian banned the pictorial representation of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes, destroying much early artistic history. The West condemned Leo's iconoclasm.[273]

East Central Europe

Throughout the Balkan Peninsula,[note 17] and the area north of the Danube,[note 18] Christianization and political centralization went hand in hand creating what is now East-Central Europe.[274][275] Local elites wanted to convert because they gained prestige and power through matrimonial alliances and participation in imperial rituals.[276][note 19]

Saints Cyril and Methodius played the key missionary roles in spreading Christianity to the Slavic people beginning in 863.[277] For three and a half years, they translated the Gospels into the Old Church Slavonic language, developing the first Slavic alphabet, and with their disciples, the Cyrillic script.[278][279] It became the first literary language of the Slavs and, eventually, the educational foundation for all Slavic nations.[278]

1100 – 1500 The rise and fall of Christendom

Before there was a political Europe, western societies worked toward creating Christendom: a loosely interdependent community of Christian kingdoms and peoples with a shared religious tradition.[280] Between 1000 and 1300, the Church became the leading institution of this world that was becoming increasingly refined, educated and secular. After 1300, the Church was riddled with corruption and entered into a decline that ended in the division of the Church.[281] The intense and rapid changes of this period are considered some of the most significant in the history of Christianity.[282]

Age of synthesis

Between 1150 and 1200, intrepid Christian scholars traveled to formerly Muslim locations in Sicily and Spain.[283] Fleeing Muslims had abandoned their libraries, and among the treasure trove of books, the searchers found the works of Aristotle and Euclid and more. What had been lost to the West after the collapse of the empire, was found, and its rediscovery created a paradigm shift in the history of Christianity.[284]

Insights gained from Aristotle dramatically impacted the Church, triggering a period of upheaval that Matthews and Platt say, one "modern historian has called the twelfth century renaissance". This included the beginning of Scholasticism and the writings of Thomas Aquinas.[266]

One aspect of this upheaval included a revival of the scientific study of natural phenomena. Robert Grosseteste (1175-1253) devised a step-by-step scientific method that used math and the testing of hypotheses; William of Ockham (1300-1349) developed a principle of economy to remove the irrelevant; Roger Bacon (1220-1292) advocated for an experimental method that he used in his study of optics.[285] Historians of science credit these and other medieval Christians with the beginnings of what, in time, became modern science and led to the scientific revolution in the West.[286][287][288][289]

The reconciliation of reason and faith, produced through Aristotle by Aquinas and the scholastics, made the 1100s and the 1200s into an age of synthesis of the secular and Christian. According to Matthews and Platt, this synthesis formed a new foundation for society with the ability to support what would become the future societies of Western Europe.[290]

Reform

In both the East and West, the Church of 1100-1200 had immense authority. The key to its power in Europe was three monastic reformation movements that swept the continent.[291][292] Owing to its stricter adherence to the reformed Benedictine rule, the Abbey of Cluny, first established in 910, became the leading centre of Western monasticism into the early twelfth century.[293][282] The Cistercian movement was the second wave of reform after 1098, when they became a primary force of technological advancement and diffusion in medieval Europe.[294]

Beginning in the twelfth century, the pastoral Franciscan Order was instituted by the followers of Francis of Assisi; later, the Dominican Order was begun by St. Dominic. Called Mendicant orders, they represented a change in understanding a monk's calling as contemplative, instead seeing it as a call to actively reform the world through preaching, missionary activity, and education.[295][296]

This new calling to reform the world led the Dominicans to dominate the new universities, travel about preaching against heresy, and to participate in the Medieval Inquisition, the Albigensian Crusade and the Northern Crusades.[297] Christian policy denying the existence of witches and witchcraft would later be challenged by the Dominicans allowing them to participate in witch trials.[298][299]

Beliefs and practices

According to Matthews and Platt, the Church had influence in every facet of medieval life due not only to monastic reform, but also to the "tireless work of the clergy and the powerful effect of the Christian belief system".[300] Most medieval people believed that participating in the sacraments, (baptism, confirmation, the Eucharist, penance, marriage, last rights, and ordination for priests), and living morally, granted them Heaven.[301] Confession and penance had become widespread from the eleventh century, and by 1300, were an integral part of both ritual and belief.[294]

Gregorian Reform established new law requiring the consent of both parties before a marriage could be performed, a minimum age for marriage, and codified marriage as a sacrament.[302][303] Thirteenth century theologians made the union a binding contract, making abandonment prosecutable with dissolution of marriage overseen by Church authorities.[304] Although the Church abandoned tradition to allow women the same rights as men to dissolve a marriage, in practice men were granted dissolutions more frequently than women.[305][306]

Throughout the Middle Ages, abbesses and female superiors of monastic houses were powerful figures whose influence could rival that of male bishops and abbots.[307][308]

The veneration of Mary developed within the monasteries in western medieval Europe.[309] Rachel Fulton writes that medieval European Christians praised Mary for making God tangible.[310][note 20]

Christian mysticism abounded in the Middle Ages, particularly among nuns and monks, inspiring believers to transcend the material realm.[312] People equated the purpose of Scripture with that of the Church. "Yet so benevolently disguised", Christopher Ocker writes, "the Bible could infiltrate and unsettle any region of late medieval Europe’s cultural worlds".[313]

Scholars of the Renaissance created textual criticism which exposed the Donation of Constantine as a forgery. Popes of the Middle Ages had depended upon the document to prove their political authority.[314]

The church became a leading patron of art and architecture and commissioned and supported such artists as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, Fra Angelico, Donatello, and Leonardo da Vinci.[315]

Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation leading to the development of classical music and all its derivatives.[316]

Centralization and persecution (1100-1300)

In the pivotal twelfth century, Europe began laying the foundation for its gradual transformation from the medieval to the modern.[317] As States became increasingly secular, they began focusing on building their own kingdoms, rather than Christendom, by centralizing power into the State. To accomplish this, they attacked the older, local, kinship-based systems by defining minorities as a threat to the social order, then using stereotyping, propaganda and the new courts of inquisition to prosecute them.[318][319] Persecution became a core element and a functional tool of power in the political development of Western society.[320][321][322] By the 1300s, segregation and discrimination in law, politics, and the economy, had become established in all European states.[323][324][325][326][note 21]

According to Moore, the church did not lead in this, but supported, then followed the State, in that centralization and secularization also took place within the church.[333][334][335][336] The Church of this era became a large, multilevel organization with the Pope at the peak of a strict hierarchy. Supporting him were layers of staff, administrators and advisers: the papal curia. An entire system of courts formed the judicial branch.[300]

Both civil and canon law became a major aspect of church culture.[334][335][336] Most bishops and Popes were trained lawyers rather than theologians.[334] According to the Oxford Companion to Christian Thought, the Church of the 1300s developed "the most complex religious law the world has ever seen, a system in which equity and universality were largely overlooked".[334][note 22]

Canon law of the Catholic Church (Latin: jus canonicum)[338] was the first modern Western legal system, and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West,[339] predating European common law and civil law traditions.[340] Justinian I's reforms had a clear effect on the evolution of jurisprudence, and Leo III's Ecloga influenced the formation of legal institutions in the Slavic world.[341]

Inquisition

The history of the Inquisition divides into two major parts: its Papal creation in the early twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and its transformation into permanent secular governmental bureaucracies between 1478 and 1542.[342] The Medieval Inquisition included the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230) and the later Papal Inquisition (1230s–1240s). They were both a type of criminal court run by the Roman Catholic Church and local secular leaders dealing largely, but not exclusively, with religious issues such as heresy.[343] Local law delivered the accused to the court, sometimes using torture for interrogation, while religious inquisitors stood by as recording witnesses.[344]

The medieval inquisition was not a unified institution.[345][346] Many parts of Europe had erratic inquisitions or none at all.[345] Jurisdiction was local, limited, and lack of support and opposition often obstructed it.[345] Inquisition was contested stridently as "unchristian" and "a destroyer of [the] gospel legacy", both in and outside the church.[347]

Historian Helen Rawlings says, "the Spanish Inquisition was different [from earlier inquisitions] in one fundamental respect: it was responsible to the crown rather than the Pope and was used to consolidate state interest.[348]

The Portuguese Inquisition, in close relationship with the Church, was also controlled by the crown who established a government board, known as the General Council, to oversee it. The Grand Inquisitor, chosen by the king, was nearly always a member of the royal family.[349]

T. F. Mayer, historian, writes that "the Roman Inquisition operated to serve the papacy's long standing political aims in Naples, Venice and Florence".[350] Its activity was primarily bureaucratic. The Roman Inquisition is probably best known for its condemnation of Galileo.[351]

Church militant

The rise of Islam (600 to 1517) had unleashed a series of Arab military campaigns that conquered Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia by 650, and added North Africa and most of Spain by 740. Only the Franks and Constantinople had been able to withstand this medieval juggernaut.[352]

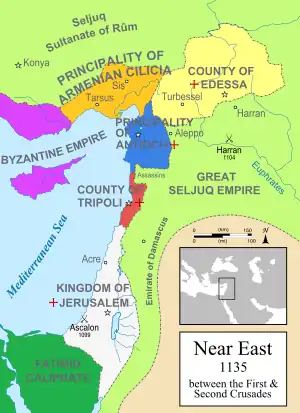

After 1071, when the Seljuk Turks closed Christian pilgrimages and defeated the Byzantines at Manzikert, the Emperor Alexius I asked for aid from Pope Urban II. Jaroslav Folda writes that Urban II responded by calling upon the knights of Christendom at the Council of Clermont on 27 November 1095, to "go to the aid of their brethren in the Holy Land and to liberate the Christian Holy sites from the heathen".[353] The First Crusade captured Antioch in 1099, then Jerusalem, establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Second Crusade occurred in 1145 when Edessa was taken by Islamic forces.

When the Pope, Blessed Eugenius III (1145–1153), called for the Second Crusade, Saxon nobles in Eastern Europe refused to go.[354] These rulers saw crusade as a tool for territorial expansion, alliance building, and the empowerment of their own church and state.[355] The free barbarian people around the Baltic Sea had been raiding the countries that surrounded them, stealing crucial resources, killing, and enslaving captives since the days of Charlemagne (747–814).[356] Subduing the Baltic area was therefore more important to the Eastern nobles.[354]

In 1147, Eugenius' Divini dispensatione, gave the eastern nobles crusade indulgences for the Baltic area.[354][357][358] The Northern, (or Baltic), Crusades followed, taking place, off and on, with and without papal support, from 1147 to 1316.[359][360][361] According to Fonnesberg-Schmidt, "While the theologians maintained that conversion should be voluntary, there was a widespread pragmatic acceptance of conversion obtained through political pressure or military coercion" from the Baltic wars.[362]

In the Levant, Christians held Jerusalem until 1187 and the Third Crusade when Richard the Lionheart defeated the significantly larger army of the Ayyubid Sultanate led by Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, begun by Innocent III in 1202 was subverted by the Venetians. They funded it, then ran out of money and instructed the crusaders to go to Constantinople and get money there. Crusaders sacked the city and other parts of Asia Minor, established the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Minor, and contributed to the downfall of the Byzantine Empire. Five numbered crusades to the Holy Land culminated in the siege of Acre of 1219, essentially ending Western presence in the Holy Land.[363] Crusades led to the development of national identities in European nations, increased division with the East, and produced cultural change for all involved.[364][365]

Albigensian Crusade

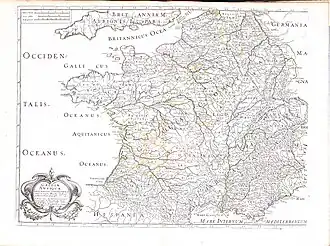

.svg.png.webp)

After decades of calling upon secular rulers for aid in dealing with the Cathars, also known as Albigensians, and getting no response,[366] Pope Innocent III and the king of France, Philip Augustus, joined in 1209 in a military campaign that was put about as necessary for eliminating the Albigensian heresy.[367][368] Once begun, the campaign quickly took a political turn. Scholars disagree on whether the course of the war was determined more by the Pope or King Philip.[369][note 23]

Throughout the campaign, Innocent vacillated, sometimes taking the side favoring crusade, then siding against it and calling for its end.[374][note 24] In 1229, when the crusade finally did end, the campaign no longer had crusade status. The army had seized and occupied the lands of nobles who had not sponsored Cathars, but had been in the good graces of the church, which had been unable to protect them. The entire region came under the rule of the French king and became southern France. Catharism continued for another hundred years (until 1350).[377][378]

Iberian Reconquista

Between 711 and 718, the Iberian peninsula had been conquered by Muslims in the Umayyad conquest.[note 25] The military struggle to reclaim the peninsula from Muslim rule took place for centuries until the Christian Kingdoms reconquered the Moorish state of Al-Ándalus in 1492.[385]

Isabel and Ferdinand married in 1469, united Spain with themselves as the first king and queen, fought the Muslims in the Reconquista and soon after established the Spanish Inquisition.[386]

The Spanish inquisition was originally authorized by the Pope in answer to royal fears that Conversos or Marranos (Jewish converts) were spying and conspiring with the Muslims to sabotage the new state. "New Christians" had begun to appear as a socio-religious designation and legal distinction.[385][387] Muslim converts were known as Moriscos.[388]

Early inquisitors proved so severe that the Pope soon opposed the Spanish Inquisition and attempted to shut it down.[389] Ferdinand declined, and is said to have pressured the Pope so that, in October 1483, a papal bull conceded control of the inquisition to the Spanish crown.[390] According to Spanish historian José Casanova, the Spanish inquisition became the first truly national, unified and centralized state institution.[391]

Power and decline

After reaching its high point in 1200, the Church began, around 1300, to sink into a long decline that led to the breaking apart of Christendom in the 1500s.[392][393]

The popes of the fourteenth century focused on power and politics. Elite Italian families used their wealth to secure episcopal offices while popes worked to centralize power into the papal position and build a papal monarchy.[333][394][395] These popes were greedy and corrupt and so caught up in politics that they no longer focused on meeting the pressing moral and spiritual needs of the church or the people it served.[281]

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries people experienced plague, famine and war that ravaged most of the continent. There was social unrest, urban riots, peasant revolts and renegade feudal armies. They faced all of this with a church unable to provide much moral leadership because of its own internal conflict and corruption.[396] Devoted and virtuous nuns and monks became increasingly rare, and monastic reform, which had been a major force, was largely absent.[397]

Popes began losing prestige and power.[398] Pope Boniface VII (1294-1303) wrote a papal bull in 1302 claiming papal superiority over all secular rulers. Philip IV, king of France, answered by sending an army to arrest him. Boniface fled for his life.[398]

In 1309, Pope Clement V moved to Avignon in southern France in search of relief from Rome's factional politics.[399] Seven popes resided there in the Avignon Papacy, developing a reputation for corruption and greed, until Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377.[400][401] After Gregory's death, the papal conclave met in 1378, in Rome, and elected an Italian Urban VI to succeed Gregory.[399] The French cardinals did not approve, so they held a second conclave electing Robert of Geneva instead. This began the Western Schism.[402][399]

_%E2%80%93_Pinacoteca_Ambrosiana.jpg.webp)

In 1409, the Pisan council called for the resignation of both popes, electing a third to replace them. Both Popes refused to resign, giving the Church three popes. The pious became disgusted, leading to an increasing loss of papal prestige and the alienation of much of western Christendom.[399][404] Five years later, the Holy Roman Emperor called the Council of Constance (1414–1418), deposed all three popes, and in 1417, elected Pope Martin V in their place.[399]

Around the same time these events began, John Wycliffe (1320–1384), an English scholastic philosopher and theologian, urged the church to give up its property (which produced much of the church's wealth), and to once again embrace poverty and simplicity, to stop being subservient to the state and its politics, and to deny papal authority.[405][406] He was accused of heresy, convicted and sentenced to death, but died before implementation. The Lollards followed his teachings, played a role in the English Reformation, and were persecuted for heresy after Wycliffe's death.[406][407]

Jan Hus (1369–1415), a Czech based in Prague, was influenced by Wycliffe and spoke out against the abuses and corruption he saw in the Catholic Church there.[408] He was also accused of heresy and condemned to death.[407][408][406] After his death, Hus became a powerful symbol of Czech nationalism and the impetus for the Bohemian/Czech and German Reformations.[409][410][408][406]

In the East

Intense missionary activity between the fifth and eighth centuries led to eastern Iran, Arabia, central Asia, China, the coasts of India and Indonesia adopting Nestorian Christianity. Syrian Nestorians also settled in the Persian Empire.[411] The Copts, Melkites, Nestorians, and the Monophysites sometimes called Jacobites in Syria, continued to exist in lands that came under Muslim rule.[412] Islam set the social norm as Christians were dhimma. This cultural status guaranteed Christians rights of protection, but discriminated against them through legal inferiority.[412] Christianity declined demographically, culturally and socially.[413] By the end of the eleventh century, Christianity was in full retreat in what had been Mesopotamia (interior Iran - Nisibis, Basra, Irbil, Mosul), but the Christian communities further to the east continued to exist.[411]

Many differences between East and West had existed since Antiquity. There were disagreements over whether Pope or Patriarch should lead the Church, whether mass should be conducted in Latin or Greek, whether priests must remain celibate, and other points of doctrine such as the Filioque Clause which was added to the Nicene creed by the west. These were intensified by cultural, geographical, geopolitical, and linguistic differences.[162][414][415] Eventually, this produced the East–West Schism, also known as the "Great Schism" of 1054, which separated the Church into Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[414]

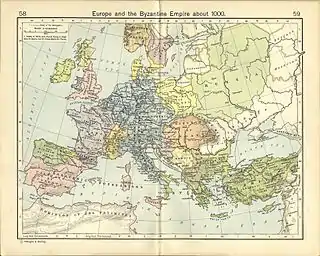

.jpg.webp)

Byzantium had, long before this, reached its greatest territorial extension in the sixth century under Justinian I. For the next 800 years, it steadily contracted under the onslaught of its hostile neighbors in both East and West.[159] After 1302, the Ottoman Empire was built upon the ruins of what had once been the great Byzantine Empire.[162]

Historians Matthews and Platt write that, by 1330, the Ottomans had "absorbed Asia Minor, and by 1390 Serbia and Bulgaria were Turkish provinces. In 1453, when the Turks finally took Constantinople, they ravaged the city for days... [ending] the last living vestige of Ancient Rome ... ".[418]

The flight of Eastern Christians from Constantinople, and the manuscripts they carried with them, is one of the factors that prompted the literary renaissance in the West.[419][note 26]

The Russian church

In a defining moment in 1380, Grand Prince Dmitrii of Moscow faced the army of the Golden Horde on Kulikovo Field near the Don River, there defeating the Mongols. Michael Angold writes that this began a period of transformation fusing state power and religious mission: thereafter "a disparate collection of warring principalities" formed "into an Orthodox nation, unified under tsar and patriarch and self-consciously promoting both a national faith and an ideology of a faithful nation".[429]

1500 – 1750

Following the geographic discoveries of the 1400s and 1500s, increasing population and inflation led the emerging nation-states of Portugal, Spain, and France, the Dutch Republic, and England to explore, conquer, colonize and exploit the newly discovered territories and their indigenous peoples.[434] Different state actors created colonies that varied widely.[435] Some colonies had institutions that allowed native populations to reap some benefits. Others became extractive colonies with predatory rule that produced an autocracy with a dismal record.[436]

Colonialism opened the door for Christian missionaries who accompanied the early explorers, or soon followed them.[437][438] Although most missionaries avoided politics, they also generally identified themselves with the indigenous people amongst whom they worked and lived.[439] According to Dana L. Robert, for 500 years, vocal missionaries challenged colonial oppression and defended human rights, even opposing their own governments in matters of social justice.[439]

Historians and political scientists see the establishment of unified, sovereign, nation-states, which led directly to the development of modern Europe, as a singularly important political development of the sixteenth century. However, while sovereign states were unifying, Christendom was coming apart.[440][441][442][443] These events contributed to the development of political absolutism beginning in 1600,[444] the return of the aristocracy to prominence, and the Enlightenment.[445]

Reformation and response

The break up of Christendom culminates in the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648). Beginning with Martin Luther nailing his Ninety-five Theses to the church door in Wittenburg in 1517, there was no actual schism until 1521 when edicts handed down by the Diet of Worms condemned Luther and officially banned citizens of the Holy Roman Empire from defending or propagating his ideas.[446]

Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and many others protested against corruptions such as simony (the buying and selling of church offices), the holding of multiple church offices by one person at the same time, and the sale of indulgences. The Protestant position later included the Five solae (sola scriptura, sola fide, sola gratia, solus Christus, soli Deo gloria), the priesthood of all believers, Law and Gospel, and the two kingdoms doctrine.

Three important traditions to emerge directly from the Reformation were the Lutheran, Reformed, and the Anglican traditions.[447] Beginning in 1519, Huldrych Zwingli spread John Calvin's teachings in Switzerland leading to the Swiss Reformation.[448]

At the same time in Germany and Switzerland, a collection of loosely related groups that included Anabaptists, Spiritualists, and Evangelical Rationalists, began the Radical Reformation.[449] They opposed Lutheran, Reformed and Anglican church-state theories, supporting instead a full separation from the state.[450]

Counter-reformation

The Roman Catholic Church soon struck back with opposition and by launching its own Counter-Reformation beginning with Pope Paul III (1534 - 1549), the first in a series of 10 reforming popes from 1534-1605.[451] In an effort to reclaim morality, a list of books detrimental to faith or morals was established, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which included the works of Luther, Calvin and other Protestants along with writings condemned as obscene.[452]

New monastic orders arose including the Jesuits.[453] Resembling a military company in its hierarchy, discipline, and obedience, their vow of loyalty to the Pope set them apart from other monastic orders, leading them to be called "the shock troops of the papacy". Jesuits soon became the Church's chief weapon against Protestantism.[453]

Monastic reform also led to the development of new, yet orthodox forms of spirituality, such as that of the Spanish mystics and the French school of spirituality.[454]

The Council of Trent (1545–1563) denied each Protestant claim, and laid the foundation of Roman Catholic policies up to the twenty-first century.[455]

War

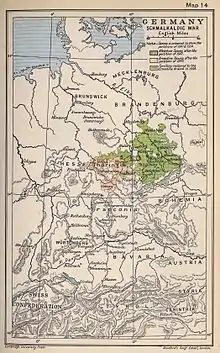

Reforming zeal and Catholic denial spread through much of Europe, and became entangled with local politics. Already involved in dynastic wars, the quarreling royal houses became polarized into the two religious camps.[456] "Religious" wars resulted ranging from international wars to internal conflicts. War began in the Holy Roman Empire with the minor Knights' Revolt in 1522, then intensified in the First Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547) and the Second Schmalkaldic War (1552-1555).[457][458] Seven years after the Peace of Augsburg, France became the centre of religious wars which lasted 36 years.[459] The final wave was the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). The involvement of foreign powers made it the largest and most disastrous.[460]

The causes of these wars were mixed. Many scholars see them as fought to obtain security and freedom for differing religious confessions, however, scholars have largely interpreted these wars as struggles for political independence that coincided with the break up of medieval empires into the modern nation states.[461][459][note 27]

Tolerance

War had been fueled by the "unquestioning assumption that a single religion should exist within each community" say Matthews and Platt.[466] However, debate on toleration now occupied the attention of every version of the Christian faith.[467] Debate centered on whether peace required allowing only one faith and punishing heretics, or if ancient opinions defending leniency, based on the parable of the tares, should be revived.[467]

Radical Protestants steadfastly sought toleration for heresy, blasphemy, Catholicism, non-Christian religions, and even atheism.[468] Anglicans and Christian moderates also wrote and argued for toleration.[469] Deism emerged, and in the 1690s, following debates that started in the 1640s, a non-Christian third group also advocated for religious toleration.[470][471] It became necessary to rethink on a political level, all of the State's reasons for persecution.[467] Over the next two and a half centuries, many treaties and political declarations of tolerance followed, until concepts of freedom of religion, freedom of speech and freedom of thought became established in most western countries.[472][473][474]

Science and the Galileo Affair

In 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), describing observations made with his new telescope that planets moved. Since Aristotle's rediscovery in the 1100s, western scientists, along with the Catholic Church, had adopted Aristotle's physics and cosmology with the earth fixed in place.[475][286] Jeffrey Foss writes that, by Galileo's time the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic view of the universe was "fully integrated with Catholic theology".[476]

The majority of Galileo's fellow scientists had no telescope, and Galileo had no theory of physics to explain how planets could orbit the sun, since according to Aristotelian physics, that was impossible. (The physics would not be resolved for another hundred years.) Galileo's peers rejected his assertions and alerted the authorities.[477] The Church forbade Galileo from teaching it. Instead, Galileo published his books.[476] He was summoned before the Roman Inquisition twice. First warned, he was next sentenced to house arrest on a charge of "grave suspicion of heresy".[478]

French historian Louis Châtellier writes that Galileo's condemnation - as a devoted Catholic - caused much consternation and private discussion about whether the judges were condemning Galileo, or the "new science" and anyone who attempted to displace Aristotle.[479] Châtellier concludes, "...the relationship between scientific thinkers and ecclesiastical authorities [became] marked by reciprocal mistrust" which has waxed and waned into the modern day.[480][481][482][478]

Witch trials (c. 1450 – 1750)

Until the 1300s, the official position of the Roman Catholic Church was that witches did not exist.[483][note 28] While historians have been unable to pinpoint a single cause of what became known as the "witch frenzy", scholars have noted that, without changing church doctrine, a new but common stream of thought developed at every level of society that witches were both real and malevolent.[487] Records show the belief in magic had remained so widespread among the rural people that it has convinced some historians Christianization had not been as successful as previously supposed.[488][note 29]

Enlightenment

There has long been an established consensus that the Enlightenment was anti-Christian, anti-Church and anti-religious.[492] However, twenty-first century scholars tend to see the relationship between Christianity and the Enlightenment as complex with many regional and national variations.[493][492] According to Helena Rosenblatt, the Enlightenment was not just a war with Christianity, since many changes to the Church were advocated by Christian moderates.[494]

In Margaret Jacob's view, critique of Christianity began among the more extreme Protestant reformers who were enraged by fear, tyranny and persecution.[495][496] According to Jacob, it was the abuses inherent in political absolutism, practiced by kings and supported by Catholicism, that caused the virulent anti-clerical, anti-Catholic, and anti-Christian sentiment that emerged in the 1680s.[497][note 30]

Enlightenment shifted the paradigm, and various ground-breaking discoveries such as Galileo's, led to the Scientific revolution (1600-1750) and an upsurge in skepticism. Virtually everything in western culture was subjected to systematic doubt including religious beliefs.[504] Biblical criticism emerged using scientific historical and literary criteria, and human reason, to understand the Bible.[505] This new approach made study of the Bible secularized and scholarly, and more democratic, as scholars began writing in their own languages making their works available to a larger public.[506]

After 1750, secularization at every level of European society can be observed.[507]

1750 – 1945

"So turbulent was the period between 1760 and 1830 that today it is considered a historical watershed" write Matthews and Platt.[508] Monarchies fell, old societies were swept away, the class system realigned, and the changed social order altered the world.[509]

The center of the old religion moved to the New World.[510] Throughout the revolutionary period, English speaking Protestant Christianity was the majority religion and played the most visible role in supporting revolution. Martin Marty writes that, in addition to being a political and economic revolution, the War of Independence and its aftermath included the legal assurance of religious freedom marking a "new order of ages".[511]

Awakenings

Change also took the form of a revival known as the First Great Awakening, which swept through the American colonies between the 1730s and the 1770s. Both religious and political in nature, it had roots in German Pietism and British Evangelicalism, and was a response to the extreme rationalism of biblical criticism, the anti-Christian tenets of the Enlightenment, and its threat of assimilation by the modern state.[512][513][514][515]

Beginning among the Presbyterians, revival quickly spread to Congregationalists (Puritans) and Baptists, creating American Evangelicalism and Wesleyan Methodism.[516] Battles over the movement and its dramatic style raged at both the congregational and denominational levels. This caused the division of American Protestantism into political 'Parties', for the first time, which eventually led to critical support for the American Revolution.[517]

In places like Connecticut and Massachusetts, where one denomination received state funding, churches now began to lobby local legislatures to end that inequity by applying the Reformation principle separating church and state.[513] Theological pluralism became the new norm.[518]

The Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s) extolled moral reform as the Christian alternative to armed revolution. They established societies, separate from any church, to begin social reform movements concerning abolition, women's rights, temperance and to "teach the poor to read".[519] These were pioneers in developing nationally integrated forms of organization, a practice which businesses adopted that led to the consolidations and mergers that reshaped the American economy.[520] Here lie the beginnings of the Latter Day Saint movement, the Restoration Movement and the Holiness movement.

The Third Great Awakening began from 1857 and was most notable for taking the movement throughout the world, especially in English speaking countries.[521] The Fourth Great Awakening of the sixties - what political scientist Hugh Heclo describes as "a plastic term reaching backward to the mid-1950s and forward to the mid-1970s" - remains a debated concept.[522]

Restorationists were prevalent in America, but they have not described themselves as a reform movement but have, instead, described themselves as restoring the Church to its original form as found in the book of Acts. It gave rise to the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement, Adventism, and the Jehovah's Witnesses.[523][524]

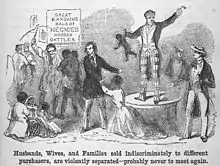

This was a period of "revolution and reaction", when "the West turned away from the past" in the hope of creating a new order of social justice, as Matthews and Platt have written.[525] For over 300 years, Christian Europe had participated in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Historian Christopher Brown interprets this as Christianity being as complicit in the expansion of slavery as it was central to its demise.[526]

Moral objections had surfaced very soon after the establishment of the trade.[note 31] In the earliest instances, denunciations came from Catholic priests.[529][note 32] Next, emerging in the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and followed by Methodists, Presbyterians and Baptists, abolitionists campaigned, wrote, and spread pamphlets against the Atlantic slave trade. Quakers helped guide these tracts into print and organized the first anti-slavery societies.[531] The Second Great Awakening continued the call.[532][533]

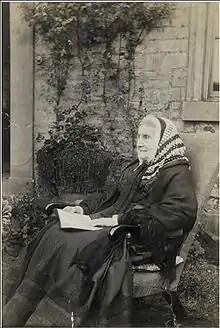

.jpg.webp)

In the years after the American Revolution, black congregations sprang up around the English speaking world led by black preachers who brought revival, promoted communal and cultural autonomy, and provided the institutional base for keeping abolitionism alive.[534][note 33]

Abolitionism did not flourish in absolutist states.[536] It was the Protestant revivalists who followed the Quaker example, African Americans themselves and the new American republic, that led to the "gradual but comprehensive abolition of slavery" in the West.[537]

Church, state and society

Revolution broke the power of the Old World aristocracy, offered hope to the disenfranchised, and enabled the middle class to reap the economic benefits of the Industrial Revolution.[538] Scholars have since identified a positive correlation between the rise of Protestantism and human capital formation,[539] work ethic,[540] economic development,[541] and the development of the state system.[542] Weber says this contributed to economic growth and the development of banking across Northern Europe.[543][544][note 34]

Missions

While the sixteenth century is generally seen as the "great age of Catholic expansion", the nineteenth century was that for Protestantism.[548] Missionaries had a significant role in shaping multiple nations, cultures and societies.[58] A missionary's first job was to get to know the indigenous people and work with them to translate the Bible into their local language. Approximately 90% were completed, and the process also generated a written grammar, a lexicon of native traditions, and a dictionary of the local language. This was used to teach in missionary schools resulting in the spread of literacy.[549][550][551]

Lamin Sanneh writes that native cultures responded with "movements of indigenization and cultural liberation" that developed national literatures, mass printing, and voluntary organizations which have been instrumental in generating a democratic legacy.[549][552] On the one hand, the political legacies of colonialism include political instability, violence and ethnic exclusion, which is also linked to civil strife and civil war.[553] On the other hand, the legacy of Protestant missions is one of beneficial long-term effects on human capital, political participation, and democratization.[554]

In America, missionaries played a crucial role in the acculturation of the American Indians.[555][556][557] The history of boarding schools for the indigenous populations in Canada and the US shows a continuum of experiences ranging from happiness and refuge to suffering, forced assimilation, and abuse. The majority of native children did not attend boarding school at all. Of those that did, many did so in response to requests sent by native families to the Federal government, while many others were forcibly taken from their homes.[558] Over time, missionaries came to respect the virtues of native culture, and spoke against national policies.[555]

Twentieth century

Liberal Christianity, sometimes called liberal theology, is an umbrella term for religious movements within late 18th, 19th and 20th-century Christianity. According to theologian Theo Hobson, liberal Christianity has two traditions. Before the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, liberalism was synonymous with Christian Idealism in that it imagined a liberal State with political and cultural liberty.[559]

The second tradition was from seventeenth century rationalism's efforts to wean Christianity from its "irrational cultic" roots.[560] Lacking any grounding in Christian "practice, ritual, sacramentalism, church and worship", liberal Christianity lost touch with the fundamental necessity of faith and ritual in maintaining Christianity.[561] This led to the birth of fundamentalism and liberalism's decline.[562]

Fundamentalist Christianity is a movement that arose mainly within British and American Protestantism in the late 19th century and early 20th century in reaction to modernism.[563] Before 1919, fundamentalism was loosely organized and undisciplined. Its most significant early movements were the holiness movement and the millenarian movement with its premillennial expectations of the second coming.[564]

In 1925, fundamentalists participated in the Scopes trial, and by 1930, the movement appeared to be dying.[565] Then in the 1930s, Neo-orthodoxy, a theology against liberalism combined with a reevaluation of Reformation teachings, began uniting moderates of both sides.[566] In the 1940s, "new-evangelicalism" established itself as separate from fundamentalism.[567] Today, fundamentalism is less about doctrine than political activism.[568]

Under Nazism

Pope Pius XI declared – Mit brennender Sorge (English: "With rising anxiety") – that Fascist governments had hidden "pagan intentions" and expressed the irreconcilability of the Catholic position with totalitarian fascist state worship which placed the nation above God, fundamental human rights, and dignity.[569]

Catholic priests were executed in concentration camps alongside Jews; 2,600 Catholic priests were imprisoned in Dachau, and 2,000 of them were executed (cf. Priesterblock). A further 2,700 Polish priests were executed (a quarter of all Polish priests), and 5,350 Polish nuns were either displaced, imprisoned, or executed.[570] Many Catholic laymen and clergy played notable roles in sheltering Jews during the Holocaust, including Pope Pius XII. The head rabbi of Rome became a Catholic in 1945 and, in honour of the actions the pope undertook to save Jewish lives, he took the name Eugenio (the pope's first name).[571]

Most leaders and members of the largest Protestant church in Germany, the German Evangelical Church, which had a long tradition of nationalism and support of the state, supported the Nazis when they came to power.[572] A smaller contingent, about a third of German Protestants, formed the Confessing Church which opposed Nazism. In a study of sermon content, William Skiles says "Confessing Church pastors opposed the Nazi regime on three fronts... first, they expressed harsh criticism of Nazi persecution of Christians and the German churches; second, they condemned National Socialism as a false ideology that worships false gods; and third, they challenged Nazi anti-Semitic ideology by supporting Jews as the chosen people of God and Judaism as a historic foundation of Christianity".[573]

Nazis interfered in The Confessing Church's affairs, harassed its members, executed mass arrests and targeted well known pastors like Martin Niemöller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.[574][575][note 35] Bonhoeffer, a pacifist, was arrested, found guilty in the conspiracy to assassinate Hitler and executed.[577]

Russian Orthodoxy

The Russian Orthodox Church held a privileged position in the Russian Empire, expressed in the motto of the late empire from 1833: Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Populism. Nevertheless, the Church reform of Peter I in the early 18th century had placed the Orthodox authorities under the control of the tsar. An ober-procurator appointed by the tsar ran the committee which governed the Church between 1721 and 1918: the Most Holy Synod. The Church became involved in the various campaigns of russification and contributed to anti-semitism.[578][579]

The Bolsheviks and other Russian revolutionaries saw the Church, like the tsarist state, as an enemy of the people. Criticism of atheism was strictly forbidden and sometimes led to imprisonment.[580][581] Some actions against Orthodox priests and believers included torture, being sent to prison camps, labour camps or mental hospitals, as well as execution.[582][583]

In the first five years after the Bolshevik revolution aka. the October Revolution, one journalist reported 28 bishops and 1,200 priests were executed.[585] This included people like the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna who was at this point a monastic.[note 36] Recently released evidence indicates over 8,000 were killed in 1922 during the conflict over church valuables.[586] More than 100,000 Russian clergymen were executed between 1937 and 1941.[587]

Under the state atheism of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, the League of Militant Atheists aided in the persecution of many Christian denominations, with many churches and monasteries being destroyed, as well as clergy being executed.[note 37]

Christianity since 1945

Christianity has been challenged in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by modern secularism which has become "the critical fault line in the contemporary world" according to theologian William Meyer.[591][592] New forms of religion which embrace the sacred as a deeper understanding of the self have begun.[593][594] This spirituality is private and individualistic, and differs radically from Christian tradition, dogma and ritual.[595] Theologian Gabriel Palmer-Fernandes writes that Christianity has taken many new directions resulting from this "appeal to inner experience, the renewed interest in human nature, and the influence of social conditions upon ethical reflection".[596]

The traditional church, characterized by Roman Catholicism and mainstream Protestantism, functions within society, engaging it directly through preaching, teaching ministries and service programs like local food banks. Theologically, churches seek to embrace secular method and rationality while continuing to refuse the secular worldview.[597] Sociologists Dick Houtman and Stef Aupers write that this type of Christianity has been declining in the West.[593]

Christian sects, such as the Amish and Mennonites, traditionally withdraw from, and minimize interaction with, society at large. According to the National Institute of Health, "The Old Order Amish are the fastest growing religious subpopulation in the United States".[598]

Theologian Allan Anderson has written that the 1960s saw the rise of Pentecostalism and charismatic Christianity. This mystical type of Christianity emphasizes the inward experience of personal piety and spirituality.[599][600] In 2000, approximately one quarter of all Christians worldwide were part of Pentecostalism and its associated movements.[601] By 2025, Pentecostals are expected to comprise one-third of the nearly three billion Christians worldwide.[602] Deininger writes that Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religious movement in global Christianity.[603]

New forms

In the early twentieth century, the study of two highly influential religious movements - the social gospel movement (1870s–1920s) and the global ecumenical movement (beginning in 1910) - provided the context for the development of American sociology as an academic discipline.[604] Later, the Social Gospel and liberation theology, which tend to be highly critical of traditional Christian ethics, made the "kingdom ideals" of Jesus their goal. First focusing on the community's sins, rather than the individual's failings, they sought to foster social justice, expose institutionalized sin, and redeem the institutions of society.[605][606] Ethicist Philip Wogaman says the social gospel and liberation theology redefined justice in the process.[607]

Originating in America in 1966, Black theology developed a combined social gospel and liberation theology that mixes Christianity with questions of civil rights, aspects of the Black Power movement, and responses to black Muslims claiming Christianity was a "white man's" religion.[608] Spreading to the United Kingdom, then parts of Africa, confronting apartheid in South Africa, Black theology explains Christianity as liberation for this life not just the next.[608]

Racial violence around the world over the last several decades demonstrates how troubled issues of race remain in the twenty-first century.[609] The historian of race and religion, Paul Harvey, says that, in 1960s America, "The religious power of the civil rights movement transformed the American conception of race."[610] Then the social power of the religious right responded in the 1970s by recasting evangelical concepts in political terms that included racial separation.[610] The Prosperity Gospel has since developed and become a dominant force in American religious life promoting racial reconciliation.[611]

The Prosperity gospel is an inherently flexible adaptation of the ‘Neo-Pentecostalism’ that began in the twentieth century’s last decades.[612] While globally, Prosperity discourse may represent a cultural invasion of American-ism, and may even muddy the waters between the religious, the economic and political, it has become a trans-national movement.[613] Prosperity ideas have diffused in countries such as Brazil and other parts of South America, Nigeria, South Africa, Ghana and other parts of West Africa, China, India, South Korea, and the Philippines.[614] It represents a shift in authority from Bible to charisma, and has suffered from accusations of financial fraud and sex scandals around the world, but it is critiqued most heavily by Christian evangelicals who question how genuinely Christian the Prosperity Gospel is.[615]

Feminist theology began in 1960.[616] In the last years of the twentieth century, the re-examination of old religious texts through diversity, otherness, and difference developed womanist theology of African-American women, the "mujerista" theology of Hispanic women, and insights from Asian feminist theology.[617]

Post-colonial decolonization