| History of Brisbane | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Brisbane's recorded history dates from 1799, when Matthew Flinders explored Moreton Bay on an expedition from Port Jackson, although the region had long been occupied by the Yugara and Turrbal aboriginal tribes. The town was conceived initially as a penal colony for British convicts sent from Sydney. Its suitability for fishing, farming, timbering, and other occupations, however, caused it to be opened to free settlement in 1838. The town became a municipality in 1859 and a consolidated metropolitan area in 1924. Brisbane encountered major flooding disasters in 1893, 1974, 2011 and 2022. Significant numbers of US troops were stationed in Brisbane during World War II. The city hosted the 1982 Commonwealth Games, World Expo 88, and the 2014 G20 Brisbane summit

Etymology

The name Brisbane is named to honour Sir Thomas Brisbane (1773–1860) who was Governor of New South Wales from 1821–1825. When it was given its name and declared as a town in 1834, to replace its penal colony status,[1] Brisbane was still part of the Colony of New South Wales.

Thomas Brisbane was a British Army officer and astronomer who was born in Ayrshire, Scotland.[2] The name Brisbane is associated with a Scottish clan, thought to be derived from the Anglo-French words "brise bane", meaning "break bone".[3]

Pre-European contact history

Prior to European colonisation, the Brisbane region was occupied by Aboriginal tribes, notably clans of the Yugara,[4] Turrbal[5] and Quandamooka[6] peoples. The oldest archeological site in the Brisbane region comes from Wallen Wallen Creek on North Stradbroke Island (conventional radiocarbon age: 21800±400[7]), however, settlement would likely have occurred well prior to this date.[8]

The land, the river and its tributaries were the source and support of life in all its dimensions. The river's abundant supply of food included fish, shellfish, crab, and prawns. Good fishing places became campsites and the focus of group activities. The district was defined by open woodlands with rainforest in some pockets or bends of the Brisbane River.[9]

A resource-rich area and a natural avenue for seasonal movement, Brisbane was a way station for groups travelling to ceremonies and spectacles. The region had several large (200–600 person) seasonal camps, the biggest and most important located along waterways north and south of the current city heart: Barambin or 'York's Hollow' camp (today's Victoria Park) and Woolloon-cappem (Woolloongabba/South Brisbane), also known as Kurilpa. These camping grounds continued to function well into historic times, and were the basis of European settlement in parts of Brisbane.[10]

18th Century

In 1770, British navigator James Cook, sailed through South Passage between the main offshore islands leading to the bay, which he named after James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, misspelled as 'Moreton'.[11]

The region was first explored by Europeans in 1799, when Matthew Flinders explored Moreton Bay during his expedition from Port Jackson north to Hervey Bay. He made a landing at what is now Woody Point in Redcliffe, and also touched down at Coochiemudlo Island and Pumicestone Passage. During the fifteen days he spent in Moreton Bay, Flinders was unable to find the Brisbane River.[12]

19th Century

European exploration

A permanent settlement in the region was not founded until 1823, when New South Wales Governor Thomas Brisbane was petitioned by free settlers in Sydney to send their worst convicts elsewhere and the area chosen became the city of Brisbane.

On 23 October 1823, Surveyor General John Oxley set out with a party in the cutter Mermaid from Sydney to "survey Port Curtis (now Gladstone), Moreton Bay, and Port Bowen (north of Rockhampton, 22°30′S 150°45′E / 22.5°S 150.75°E),[13] with a view to forming convict settlements there". The party reached Port Curtis on 5 November 1823. Oxley suggested that the location was unsuitable for a settlement, since it would be difficult to maintain.

As he approached Point Skirmish by Moreton Bay, he noticed several Indigenous Australians approaching him and in particular one as being "much lighter in colour than the rest". The white man turned out to be a shipwrecked timbergetter by the name of Thomas Pamphlett who, along with John Finnegan, Richard Parsons, and John Thompson had left Sydney on 21 March 1823 to sail south along the coast and bring cedar from Illawarra but during a large storm were pushed north. Not knowing where they were, the group attempted to return to Sydney, eventually being shipwrecked on Moreton Island on 16 April.[14] They lived with the Indigenous tribe for seven months.

After meeting with them, Oxley proceeded approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) up what he later named the Brisbane River in honour of the governor. Oxley explored the river as far as what is now the suburb of Goodna in the city of Ipswich, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) upstream of Brisbane's central business district. Several places were named by Oxley and his party, including Breakfast Creek (at the mouth of which they cooked breakfast), Oxley Creek, and Seventeen Mile Rocks.

The settlement struggled with diseases through the late 1820s.[15]

1824 colony

|

|

|

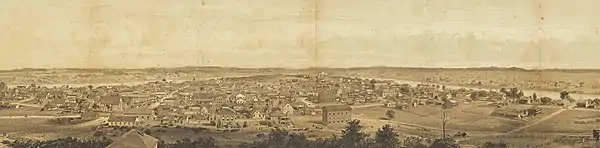

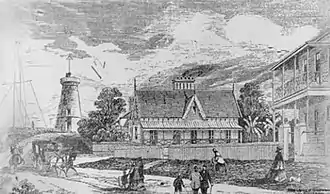

| Early map (1830-1839), the Spring Hill reservoir and Wheat Creek are visible, as well as the Government Paddocks of South Bank where the Corn Field raids occurred, (SLQ) | King's Wharf, Watercolour painting by Bowerman, Henry Boucher, c.1835

Commissariat Store built in 1829, shown lower right |

The Old Windmill built in 1828, a site of convict punishments and executions, is the oldest surviving building in Queensland |

In 1824, the first convict colony was established at Redcliffe Point under Lieutenant Henry Miller. Meanwhile, Oxley and Allan Cunningham explored further up the Brisbane River in search of water, landing at the present location of North Quay. Only one year later, in 1825, the colony was moved south from Redcliffe to a peninsula on the Brisbane River, site of the present central business district, called "Meen-jin" by its Turrbal inhabitants.

At the end of 1825, the official population of Brisbane was "45 males and 2 females". Until 1859, when Queensland was separated from the state of New South Wales, the name Moreton Bay was used to describe the new settlement and surrounding areas. "Edenglassie" was the name first proposed for the growing town by Chief Justice Francis Forbes,[16] the name taken from the Forbes' family estate in Aberdeenshire. The name soon fell out of favour and the current name in honour of Governor Thomas Brisbane was adopted instead.

The colony was originally established as a "prison within a prison"—a settlement, deliberately distant from Sydney, to which recidivist convicts could be sent as punishment. It soon garnered a reputation, along with Norfolk Island, as one of the harshest penal settlements in all of New South Wales. In July 1828 work began on the construction of the Commissariat Store. It remains intact today as a museum of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland and is only one of two convict era buildings still standing in Queensland. The other is The Old Windmill on Wickham Terrace.

Over twenty years, thousands of convicts passed through the penal colony. Hundreds of these fled the stern conditions and escaped into the bush. Although most escapes were unsuccessful or resulted in the escapees perishing in the bush, some (e.g. James Davis) succeeded in living as "wild white men" amongst the aboriginal people.

During these decades, the local aboriginals tried to "starve out" the settlement by destroying its crops—most notably their "corn fields" at today's South Bank. In retaliation, colony guards shot and killed aboriginals entering the corn fields.

Free settlement

As a penal colony, Brisbane did not permit the erection of private settlements nearby for many years. As the inflow of new convicts steadily declined, the population dropped. From the early 1830s the British government questioned the suitability of Brisbane as a penal colony. Allan Cunningham's discovery of a route to the fertile Darling Downs in 1828, the commercial pressure to develop a pastoral industry, and increasing reliance on Australian wool, as well as the expense of transporting goods from Sydney, were the major factors contributing to the opening of the region to free settlement.[17] In 1838, the area was opened up for free settlers, as distinct from convicts. An early group of Lutheran missionaries from Germany were granted land in what is now the north side suburb of Nundah.

In 1839 the first three surveyors, Dixon, Stapylton and Warner arrived in Moreton Bay to prepare the land for greater numbers of European settlers by compiling a trigonometrical survey.[18] From the 1840s, settlers took advantage of the abundance of timber in local forests. Once cleared, land was quickly utilized for grazing and other farming activities. The convict colony eventually closed.

In 1841, the Brisbane River reached over eight metres above normal during major floods in Brisbane.[19] The flood caused extensive damage to the colony.

The free settlers did not recognise local aboriginal ownership and were not required to provide compensation to the Turrbal aboriginals. Some serious affrays and conflicts ensued—most notably resistance activities of Yilbung, Dundalli, Ommuli, and others. Yilbung, in particular, sought to extract regular rents from the white population on which to sustain his people, whose resources had been heavily depleted by the settlers. By 1869, many of the Turrbal had died from gunshot or disease, but the Moreton Bay Courier makes frequent mention of local indigenous people who were working and living in the district. In fact, between the 1840s and 1860s, the settlement relied increasingly on goods obtained by trade with aboriginals—firewood, fish, crab, shellfish—and services they provided such as water-carrying, tree-cutting, fencing, ring-barking, stock work and ferrying. Some Turrbal escaped the region with the help of Thomas Petrie, who gave his name to the suburb of Petrie to the north of Brisbane.[20]

Scottish immigrants from the ship Fortitude arrived in Brisbane in 1849, enticed by Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang on the promise of free land grants. Denied land, the immigrants set up camp in York's Hollow waterholes in the vicinity of today's Victoria Park, Herston, Queensland. A number of the immigrants moved on and settled the suburb, naming it after the ship on which they arrived.[21]

The Roman Catholic church erected the Pugin Chapel in 1850, to the design by the gothic revivalist Augustus Pugin, who was then visiting the city.

Development in the early years of the colony of Queensland

On 6 September 1859, the Municipality of Brisbane was proclaimed. The next month, polling for the first council was conducted. John Petrie was elected the first mayor of Brisbane.[22] Letters patent dated 6 June 1859, proclaimed by Sir George Ferguson Bowen on 10 December 1859, separated Queensland from New South Wales, whereupon Bowen became Queensland's first governor,[23] with Brisbane chosen as the capital.[24] Old Government House was constructed in 1862 to house Sir George Bowen's family, including his wife, the noblewoman Diamantina, Lady Bowen di Roma. During the tenure of Lord Lamington, Old Government House was the likely site of the origin of Lamingtons.[25]

Unlike Sydney during the 1860s and 1870s, Brisbane had few professional artists and no art gallery.[26] Originally the neighbouring city of Ipswich was intended to be the capital of Queensland, but it proved to be too far inland to allow access by large ships, so Brisbane was chosen instead.

The City Botanic Gardens were originally established in 1825 as a farm for the Moreton Bay penal settlement, and were planted by convicts in 1825 with food crops to feed the prison colony.[27] In 1855, several acres were declared a Botanic Reserve under the Superintendent Walter Hill, a position he held until 1881.[28][29] Some of the older trees planted in the Gardens were the first of their species to be planted in Australia, due to Hill's experiments to acclimatise plants. By 1866 Hill had succeeded in having the extent of the Botanic Gardens enlarged to approximately 27 acres (11 ha). He introduced the flowering trees, the jacaranda and poinciana, which are still popular garden plants in Queensland. Indeed, it is claimed that all jacaranda trees in Australia are descended from the original jacaranda tree that grew from a seed imported by Hill in 1864.[30]

In 1864, the Great Fire of Brisbane burned through the central parts of the city, destroying upwards of 100 structures. Following the disaster, rebuilding in the city centre largely moved away from wooden buildings, and toward brick and stone.[31] The 1860s were a period of economic and political turmoil leading to high unemployment, in 1866 hundreds of impoverished workers convened a meeting at the Treasury Hotel, with a cry for "bread or blood", rioted and attempted to ransack the Government store's.[32]

Charles Tiffin was appointed as Queensland Government Architect in 1859, and pursued an intellectual policy in the design of public buildings based on Italianate and Renaissance revivalism, with such buildings as Government House, the Department of Primary Industries Building in 1866, and the Queensland Parliament built in 1867. The 1880s brought a period of economic prosperity and a major construction boom in Brisbane, that produced an impressive number of notable public and commercial buildings. John James Clark was appointed Queensland Government Architect in 1883, and continuing in Tiffin's design, asserted the propriety of the Italian Renaissance, drawing upon typological elements and details from conservative High Renaissance sources. Building in this trace of intellectualism, Clark designed the Treasury Building in 1886, and the Yungaba Immigration Centre in 1885.[33] Other major works of the era include Customs House in 1889, and the Old Museum Building completed in 1891.

Fort Lytton was constructed in 1882 at the mouth of the Brisbane river, to protect the city against foreign colonial powers such as Russia and France, and was the only moated fort ever built in Australia.

The city's slum district of Frog's Hollow was both the red light district of colonial Brisbane and its Chinatown, and was the site of Prostitution, sly grog, and opium dens. In 1888, Frog's Hollow was the site of anti-Chinese riots, where more than 2000 people attacked Chinese homes and businesses.[34][35]

The 1893 Black February floods caused severe flooding in the region and devastated the city. Raging flood waters destroyed the first of several versions of the Victoria Bridge. Even though gold was discovered north of Brisbane, around Maryborough and Gympie, most of the proceeds went south to Sydney and Melbourne. The city remained an underdeveloped regional outpost, with comparatively little of the classical Victorian architecture that characterized southern cities. In 1896, the Brisbane river saw its worst maritime disaster with the capsize of the ferry Pearl, of the 80-100 people on board, only 40 survived.[36]

A demonstration of electric lighting of lamp posts along Queen Street in 1882 was the first recorded use of electricity for public purposes in the world.[37] The first railway in Brisbane was built in 1879, when the line from the western interior was extended from Ipswich to Roma Street Station. First horse-drawn, then electric trams operated in Brisbane from 1885 until 1969.

20th Century

When the colonies united to form the Federation of Australia in 1901, celebrations were held in Brisbane to mark the event, with a triumphal arch in Queen Street. In May that year, the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) laid the foundation stone of St John's Cathedral, one of the great cathedrals of Australia. The University of Queensland was founded in 1909 and first sited at Old Government House, which became vacated as the government planned for a larger residence. Fernberg House, built in 1865, became the temporary residence in 1910, and later made the permanent government house.

The Local Authorities Act 1902 introduced the ability of a town to be designated a city with Brisbane being officially designated as one of the first three cities by the Act (the others being Rockhampton and Townsville).[38]

Tramway employees stood down for wearing union badges on 18 January 1912 sparked Australia's first General strike, the 1912 Brisbane General Strike which lasted for five weeks. The first ceremony to honour the fallen soldiers at Gallipoli was held at St John's Cathedral on 10 June 1915.[39] The tradition would later grow into the popular Anzac Day ceremony.

In 1917 during World War I, the Australian Government conducted a Raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office, with the aim of confiscating copies of Hansard that covered debates in the Queensland Parliament against where anti-conscription sentiments had been aired.

Russian immigration took place in the years 1911–1914. Many were radicals and revolutionaries seeking asylum from tsarist political repression in the final chaotic years of the Russian Empire; considerable numbers were Jews escaping state-inspired pogroms. They had fled Russia via Siberia and Northern China, most making their way to Harbin, in Manchuria, then taking passage from the port of Dalian to Townsville or Brisbane, the first Australian ports of call.[40] Following the First World War, returned servicemen of the First Australian Imperial Force were focused upon socialists and other elements of society that the ex-servicemen considered to be disloyal toward Australia.[41] Over the course of 1918–1919, a series of violent demonstrations and attacks known as the Red Flag riots, were waged throughout Brisbane. The most notable incident occurred on 24 March 1919, when a crowd of about 8,000 ex-servicemen clashed violently with police who were preventing them from attacking the Russian Hall in Merivale Street, South Brisbane, which was known as the 'Battle of Merivale street'.

In an effort to prevent overcrowding and control urban development, the Parliament of Queensland passed the Undue Subdivision of Land Prevention Act 1885,[42] preventing congestion in Queensland cities relative to others in Australia. This legislation, in addition to the construction of efficient public transport in the form of steam trains and electric trams, encouraged urban sprawl.[42] Although the initial tram routes reached out into established suburbs such as West End, Fortitude Valley, New Farm, and Newstead, later extensions and new routes encouraged housing developments in new suburbs, such as the western side of Toowong, Paddington, Ashgrove, Kelvin Grove and Coorparoo.

This pattern of development continued through to the 1950s, with later extensions encouraging new developments around Stafford, Camp Hill, Chermside, Enoggera and Mount Gravatt. Generally, these new train lines linked established communities, although the Mitchelton line (later extended to Dayboro) and before being cut back to Ferny Grove) did encourage suburban development out as far as Keperra.

Subsequently, as private motor cars became affordable, land between tram and train routes was developed for settlement, resulting in the construction of Ekibin, Tarragindi, Everton Park, Stafford Heights, and Wavell Heights.

.jpg.webp)

Amalgamation of local government areas

In 1924, the City of Brisbane Act was passed by the Queensland Parliament, consolidating the City of Brisbane and the City of South Brisbane; the Towns of Hamilton, Ithaca, Sandgate, Toowong, Windsor, and Wynnum; and the Shires of Balmoral, Belmont, Coorparoo, Enoggera, Kedron, Moggill, Sherwood, Stephens, Taringa, Tingalpa, Toombul, and Yeerongpilly to form the current City of Greater Brisbane, now known simply as the City of Brisbane, in 1925.

To accommodate the new, enlarged city council, the current Brisbane City Hall was opened in 1930. Many former shire and town halls were then remodelled into public libraries, becoming the nucleus of Greater Brisbane's branch system. During the Great Depression, a number of major projects were undertaken to provide work for the unemployed, including the construction of the William Jolly Bridge and the Wynnum Wading Pool.

Following the death of King George V in 1936, Albert square was widened to include the area which had been Albert Street, and renamed King George Square in honour of the King. An equestrian statue of the king and two Bronze Lion sculptures were unveiled in 1938.

In 1939, armed farmers marched on the Queensland Parliament and stormed the building in an attempt to take hostage the Queensland Government led by Labor Premier William Forgan Smith, in an event that became known as the 'Pineapple rebellion'.[43]

During the late 1930s construction of the Story Bridge continued. It was opened on 6 July 1940.

Brisbane during the Second World War

.jpg.webp)

Due to Brisbane's proximity to the South West Pacific Area theatre of World War II, the city played a prominent role in the defence of Australia. The city became a temporary home to thousands of Australian and American servicemen. Buildings and institutions around Brisbane were given over to the housing of military personnel as required. Wartime Brisbane was defined by the racial segregation of African American servicemen, prohibition and sly grog, crime, and jazz ballroom's.[44][45]

The present-day MacArthur Central building became the Pacific headquarters of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur,[46] and the University of Queensland campus at St Lucia was converted to a military barracks for the final three years of the war. St Laurence's College and Somerville House Girls' School in South Brisbane were also used by American forces.

During this time St Laurence's College was moved to Greenslopes to continue classes. Newstead House was also used to house American servicemen during the war. Because US authorities wanted separate recreational facilities black soldiers the Red Cross organised dances at the Doctor Carver Club in South Brisbane.[47] Sunnybank's Oasis swimming pool and gardens was also a popular rest and recreation venue for American military personnel stationed in Brisbane.[48]

Brisbane was used to mark the position of the "Brisbane Line", a controversial defence proposal allegedly formulated by the Menzies government, that would, upon a land invasion of Australia, surrender the entire northern part of the country. The line was, allegedly, at a latitude just north of Brisbane and spanned the entire width of the continent. Surviving from this period are several cement bunkers and gun forts in the northern suburbs of Brisbane and adjacent areas (Sunshine Coast/ Moreton Bay islands).

On 26 November and 27 November 1942, rioting broke out between US and Australian servicemen stationed in Brisbane. By the time the violence had been quelled one Australian soldier was dead, and hundreds of Australian and US servicemen were injured along with civilians caught up in the fighting.[49] Hundreds of soldiers were involved in the rioting on both sides. This incident, which was heavily censored at the time and apparently was not reported in the US at all, is known as the Battle of Brisbane.

Post-War Brisbane

.jpg.webp)

Immediately after the war, the Brisbane City Council, along with most governments in Australia, found it difficult to raise finances for much-needed repairs and development. Even where funds could be obtained materials were scarce. Adding to these difficulties was the political environment encouraged by some aldermen, led by Archibald Tait, to reduce the city's rates (land taxes). Ald Tait successfully ran on a slogan of "Vote for Tait, he'll lower the rate." Rates were indeed lowered, exacerbating Brisbane's financial difficulties.

Although Brisbane's tram system continued to be expanded, roads and streets remained unsealed. Water supply was limited, although the City Council built and subsequently raised the level of the Somerset Dam on the Stanley River. Despite this, most residences continued to rely heavily on rainwater stored in tanks.

The limited water supply and lack of funding also meant that despite the rapid increase in the city's population, little work was done to upgrade the city's sewage collection, which continued to rely on the collection of nightsoil. Other than the CBD and the innermost suburbs, Brisbane was a city of "thunderboxes" (outhouses) or of septic tanks.

What finances could be garnered by the council were poured into the construction of Tennyson Powerhouse, and the extension and upgrading of the powerhouse in New Farm Park to meet the growing demands for electricity. Brisbane's first modern apartment building, Torbreck at Highgate Hill, was completed in 1960.[50]

Work continued slowly on the development of a town plan, hampered by the lack of experienced staff and a continual need to play "catch-up" with rapid development. The first town plan was adopted in 1965.[51]

1961 saw the election of Clem Jones as Lord Mayor. Ald Jones, together with the town clerk J.C. Slaughter sought to fix the long-term problems besetting the city. Together they found cost-cutting ways to fix some problems. For example, new sewers were laid 4 feet deep and in footpaths, rather than 6 feet deep and under roads. In the short term, "pocket" or local sewerage treatment plants were established around the city in various suburbs to avoid the expense of developing a major treatment plants and major connecting sewers.

They were also fortunate in that finance was becoming less difficult to raise and the city's rating base had by the 1960s significantly grown, to the point where revenue streams were sufficient to absorb the considerable capital outlays.

Under Jones' leadership, the City Council's transport policy shifted significantly. The City Council hired American transport consultants Wilbur Smith to devise a new transport plan for the city.[52] They produced a report known as the Wilbur Smith "Brisbane Transportation Study" which was published in 1965. It recommended the closure of most suburban railway lines, closure of the tram and trolley-bus networks, and the construction of a massive network of freeways through the city. Under this plan the suburb of Woolloongabba would have been almost obliterated by a vast interchange of three major freeways. In 1962, one of the largest fires in Brisbane's history, the Paddington tram depot fire, destroyed 67 trams and the depot which represented about 20% of the fleet.[53] The depot's destruction generally marked the beginning of the end for trams in the city. Trams and trolley-buses were rapidly eliminated between 1968 and 1969, although only one freeway was constructed, the trains were retained and subsequently electrified. The first train line to be so upgraded was the Ferny Grove to Oxley line in 1979. The train line to Cleveland, which had been cut back to Lota in 1960, was also reopened.

In 1955, Wickham Terrace was the site of a terrorist incident involving shootings and bombs, by the German immigrant Karl Kast.

In 1973, the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub in the city's entertainment district, was firebombed that resulted in 15 deaths, in what is one of Australia's worst mass killings.[54] The 1974 Brisbane flood was a major disaster which temporarily crippled the city, and saw a substantial landslip at Corinda.

Between 1968 and 1987, when Queensland was governed by Bjelke-Petersen, whose government was characterised by social conservatism and the use of police force against demonstrators, and which ended with the Fitzgerald Inquiry into police corruption, Brisbane developed a counterculture focused on the University of Queensland, street marches and Brisbane punk rock music. In 1971, the touring Springboks were to play against the Australian Rugby team the Wallabies. This was at a time of growing international opposition to South Africa's racist apartheid policies, and The Springbok's visit allowed the Queensland Premier, Bjelke-Petersen, to declare a state of emergency for a month.[55] Police violence erupted when several hundred demonstrators assembled outside a Brisbane motel on Thursday 22 July 1971 where the Springbok team was staying. Observers claimed that the police, without warning or cause, charged at the demonstrators. On Saturday evening, a large number of demonstrators assembled once more outside the Tower Mill Motel and after 15 minutes of peaceful protest, a brick was thrown into the motel room and police took action to clear the road and consequently disproportionate violence was used against demonstrators.[56]

In the lead up to the 1980s Queensland fell subject to many forms of censorship. In 1977 things had escalated from prosecutions and book burnings, under the introduction of the Literature Board of Review, to the statewide ban on protests and street marches.

In September 1977 the Queensland Government introduced a ban on all street protests, resulting in a statewide civil liberties campaign of defiance.[57] This saw two thousand people arrested and fined, with another hundred being imprisoned, at a cost of almost five million dollars to the State Government.[58] Bjelke-Petersen publicly announced on 4 September 1977 that "the day of the political street march is over ... Don't bother to apply for a permit. You won't get one. That's government policy now."[59] In response to this, protesters came up with the idea of Phantom Civil Liberties Marches where protesters would gather and march until the police and media arrived. They would then disperse, and gather together again until the media and police returned, repeating the process over and over again.[60] The Fitzgerald Inquiry between 1987 and 1989 into Queensland Police corruption, was a judicial inquiry presided over by Tony Fitzgerald. The inquiry resulted in the resignation of the Premier (head of government), the calling of two by-elections, the jailing of three former ministers and the Police Commissioner (who also lost his knighthood). It also contributed to the end of the National Party of Australia's 32-year run as the governing political party in Queensland.

1980s

.jpg.webp)

Brisbane hosted the Commonwealth Games in 1982 and the World's Fair in 1988. The city electrified its rail network during the 1970s and 1980s. The redevelopment of South Bank, started with the monumental Robin Gibson-designed Queensland Cultural Centre, with the first stage the Queensland Art Gallery completed in 1982, the Queensland Performing Arts Centre in 1985, and the Queensland Museum in 1986. Between the late 1970s and mid-1980s, Brisbane was the focus of early land rights protests (e.g. during the Commonwealth Games) and several well-remembered clashes between students, union workers, police and the then-Queensland government. Partly from this context, innovative Brisbane music groups emerged (notably Punk groups) that added to the city's renown. In 1984, the Silver Jubilee Fountain sank to the floor of the Brisbane River. The fountain had operated since Queen Elizabeth II's Silver Jubilee visit in March 1977.[61]

Later in that decade, emission control regulation had a major effect on improving the city's air quality.[62] The banning of backyard incinerators in 1987, together with the closure of two local coal fired power stations in 1986 and a 50% decrease in lead levels found in petrol, resulted in a lowering of pollution levels. Brisbane's population growth far exceeded the national average in the last two decades of the 20th century, with a high level of interstate migration from Victoria and New South Wales. In the late 1980s Brisbane's inner-city areas were struggling with economic stagnation, urban decay and crime which resulted in an exodus of residents and business to the suburban fringe, in the early 1990s the city undertook an extensive and successful urban renewal of the Woolstore precinct in Teneriffe.[63]

21st Century

The South East Busway was established in 2000. After three decades of record population growth, Brisbane was hit again by a major flood in January 2011. The Brisbane River did not reach the same height as the previous 1974 flood, but still caused extensive damage and disruption to the city.[64][65]

The Queensland Cultural Centre was also expanded, with the completion of the State Library and the Gallery of Modern Art in 2006, and the Kurilpa Bridge in 2009, the world's largest hybrid tensegrity bridge.[66] Brisbane also hosted major international events including the final Goodwill Games in 2001, the Rugby League World Cup final in 2008 and again in 2017, as well as the 2014 G20 Brisbane summit.

The city experienced a severe hailstorm that caused significant damage in 2014.

Population growth has continued to be among the highest of the Australian capital cities in the first two decades of the 21st century, and major infrastructure including the Howard Smith Wharves, Roma Street Parklands, the Brisbane Riverwalk, the Queen's Wharf casino and resort precinct, the Brisbane International Cruise Terminal, the Clem Jones, Airport Link, and Legacy Way road tunnels, and the Airport, Springfield, Redcliffe Peninsula and Cross River Rail railway lines have been completed or are under construction. In 2019, the Brisbane Skytower became the tallest building in the city.

Brisbane is scheduled to host the 2032 Summer Olympics and Paralympics.

See also

References

- ↑ "Brisbane | Queensland, Australia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ "Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, Baronet". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ Moffet, Rodger (17 October 2021). "Clan Brisbane History". ScotClans.

- ↑ Anonymous (26 July 2019). "E23: Yuggera". collection.aiatsis.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ Anonymous (26 July 2019). "E86: Turrbal". collection.aiatsis.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ Anonymous (26 July 2019). "E21: Moondjan". collection.aiatsis.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ Reid, Jill; Ulm, Sean (2000). "Index of dates from archaeological sites in Queensland". Queensland Archaeological Research. 12: 35. doi:10.25120/qar.12.2000.78.

- ↑ Draft Design Report: Chapter 15. Aboriginal Cultural Heritage (PDF). Brisbane: Brisbane Metro. 2018. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ↑ Jones, Ryan. "Indigenous Aboriginal Sites of Southside Brisbane | Mapping Brisbane History". mappingbrisbanehistory.com.au. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ↑ Kerkhove, Ray (2015). Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane: An Historical Guide. Salibury: Boolarong Press.

- ↑ "Moreton Bay". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ "The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders". Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Port Bowen (entry 7456)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Field's New South Wales p. 89 (published 1925) Archived 20 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine see footnote

- ↑ Cameron-Sith, Alexander (28 February 2019). A Doctor Across Borders: Raphael Cilento and public health from empire to the United Nations. ANU Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-76046-265-9. JSTOR j.ctvdjrrfp.7. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ↑ Seeing South-East Queensland (2 ed.). RACQ. 1980. p. 7. ISBN 0-909518-07-6.

- ↑ Laverty, John (2009). The Making of a Metropolis: Brisbane 1823–1925. Salisbury, Queensland: Boolarong Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-9751793-5-2.

- ↑ "First surveys". History of Mapping and Surveying. Department of Natural Resources and Mines, Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ "'One of the most extreme disasters in colonial Australian history': climate scientists on the floods". Australian Geographic. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ↑ "Petrie – suburb in the Moreton Bay Region (entry 45463)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ "Fortitude Valley – suburb in City of Brisbane (entry 49857)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ Laverty, John (1974). "Petrie, John (1822–1892)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ "The Queensland Proclamation" (PDF). Queensland Government Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Evans, Raymond (2007). A History of Queensland. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780521545396.

- ↑ Shrimpton, James (6 October 2007). "Australia: The tale of Baron Lamington and an improvised cake". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ↑ de Vries, Susanna; Jake de Vries (2003). Historic Brisbane: Convict Settlement to River City. Brisbane, Australia: Pandanus Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-9585408-4-5.

- ↑ "City Botanical Gardens – Brisbane Visitors Guide". Brisbane Australia. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ↑ "BOTANIC GARDENS, BRISBANE". New South Wales Government Gazette. No. 32. New South Wales, Australia. 23 February 1855. p. 483. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Fagg, Murray (26 May 2009). "City Botanic Gardens (Brisbane)". Australian National Botanic Gardens. Council of Heads of Australian Botanic Gardens. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ Jessica Hinchliffe (1 November 2017). "Why Brisbane, not Grafton, is the original jacaranda capital of Australia". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "The Great Fire of Brisbane, 1864". State Library of Queensland. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "150th anniversary - Brisbane's Bread or Blood Riot". SLQ. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ↑ King, Stuart (2010). "Colony and Climate: Positioning Public Architecture in Queensland 1859-1909". ABE Journal. Open Edition Journals (2). doi:10.4000/abe.402. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ "Frog's Hollow, CBD". Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ Evans, Raymond. "Anti Chinese Riot: Lower Albert Street" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ "TERRIBLE DISASTER". The Brisbane Courier. National Library of Australia. 14 February 1896. p. 5. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ Dunn, Col (1985). The History of Electricity in Queensland. Bundaberg: Col Dunn. p. 21. ISBN 0-9589229-0-X.

- ↑ "Local Authorities Act of 1902 (2 Edw VII, No 19)". Queensland Historical Acts. Australasian Legal Information Institute. pp. 8366–8367. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ↑ Tony Moore (16 July 2013). "Push to remember Brisbane clergyman's role in Anzac history". Brisbane Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "St Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral (entry 600358)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 165.

- 1 2 Spearritt, Peter (March 2009). "The 200 Km City: Brisbane, The Gold Coast, And Sunshine Coast". Australian Economic History Review. 49 (1): 95. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8446.2009.00251.x. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ↑ "Raid on Parliament". Trove. 23 August 1939. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ↑ Dan Nancarrow (5 July 2012). "Theatre play explores Brisbane's boundaries". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ↑ E. J. Tait (14 August 1942). "Unspeakable orgy in Brisbane". Trove. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ↑ Dunn, Peter. "General Headquarters (GHQ) – South West Pacific Area: AMP Building, corner of Queen and Edward Streets, Brisbane". Oz at War. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ↑ Damousi, Joy; Marilyn Lake (1995). Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century. CUP Archive. p. 185. ISBN 0521457106. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑

This Wikipedia article incorporates CC-BY-4.0 licensed text from: "A Suburban Oasis: Sunnybank's Oasis Swimming Pool & Gardens". John Oxley Library Blog. State Library of Queensland. 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

This Wikipedia article incorporates CC-BY-4.0 licensed text from: "A Suburban Oasis: Sunnybank's Oasis Swimming Pool & Gardens". John Oxley Library Blog. State Library of Queensland. 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ↑ Dunn, Peter. "The Battle of Brisbane – 26 & 27 November 1942". Oz at War. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ↑ McBride, Frank; et al. (2009). Brisbane 150 Stories. Brisbane City Council Publication. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-876091-60-6.

- ↑ "Fact sheet 16. Development Assessment". Brisbane City Plan 2014. Brisbane City Council. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Allan Krosch (9 March 2009). "History of Brisbane's Major Arterial Roads: A Main Roads Perspective Part 1" (PDF). Queensland Roads, Edition 7. Department of Transport and Main Roads. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ McBride, Frank; et al. (2009). Brisbane 150 Stories. Brisbane City Council Publication. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-1-876091-60-6.

- ↑ Geoff, Plunkett (5 May 2018). The Whiskey Au Go Go massacre : murder, arson and the crime of the century. Newport, NSW. ISBN 9781925675443. OCLC 1041112112.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Bryce, Alex. "We Would Live in Peace and Tranquility and No One Would Know Anything." Australian Academic and Research Libraries 31.3(2000): 65–81. Trove. Web.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Ross. "A History of Queensland, from 1915 to the 1980s." University of Queensland Press, 1985. Print.

- ↑ Keim, Stephen. "The State of (Civil Liberties in Queensland): New Broom – Same Dirt." Legal Service Bulletin 13.1(1988):10–11. Web.

- ↑ Plunkett, Mark and Ralph Summy 'Civil Liberties in Queensland: A nonviolent political campaign.' "Social Alternatives" Vol 1 no. 6/7, 1980 p 73-90

- ↑ Bjelke-Petersen, in Patience The Bjelke-Petersen premiership 1968–1983 : issues in public policy. Longman Cheshire: Melbourne. 1985.

- ↑ Summy, Ralph. Bruce Dickson and Mark Plunkett. "Phantom Civil Liberties Marches – Queensland University 1978–79" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgyX_01P1do Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hamilton-Smith, Lexy (24 January 2018). "Find out what happened to Queen Elizabeth II's fountain in the Brisbane River". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "South East Queensland air quality trends". www.qld.gov.au. Government of Queensland. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "Brisbane City Council. Urban Renewal Brisbane - 20 Years Celebration Magazine. p 14" (PDF). Brisbane.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ↑ Berry, Petrina (13 January 2011). "Brisbane braces for flood peak as Queensland's flood crisis continues". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ↑ "Before and after photos of the floods in Brisbane". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ "Cox Rayner + Arup complete worlds largest tensegrity bridge in Brisbane". World Architecture News. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

Further reading

- J. G. Steele (1975). Brisbane Town in convict days, 1824–1842. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0702209252.

- Fisher, Rod, ed. (1990). Brisbane : the Aboriginal presence 1824-1860. Brisbane History Group. ISBN 0958782695.

- Greenwood, Gordon; Laverty, John (1959). Brisbane 1859 to 1959: a history of local government (PDF). Oswald Ziegler for the Brisbane City Council.

- Cole, John R (1984). Shaping a city: Greater Brisbane 1925-1985. William Brooks Queensland. ISBN 978-0-85568-620-8.

External links

- Australian Heritage Historical Towns Directory: Brisbane

- Brisbane Tramway Museum

- The Home Front – World War 2

- Brisbane’s role in WWII focus of new book regarding Brisbane as a large submarine base in World War II

- State Library of Queensland

- Google map of Pre 1925 merger Brisbane Councils