The region now known as Gloucestershire was originally inhabited by Brythonic peoples (ancestors of the Welsh and English and other Romano-British peoples) in the Iron Age and Roman periods. After the Romans left Britain in the early 5th century, the Brythons re-established control but the territorial divisions for the post-Roman period are uncertain. The city of Caerloyw (Gloucester today, still known as Caerloyw in modern Welsh) was one centre and Cirencester may have continued as a tribal centre as well. The only reliably attested kingdom is the minor south-east Wales kingdom of Ergyng, which may have included a portion of the area (roughly the Forest of Dean). In the final quarter of the 6th century, the Saxons of Wessex began to establish control over the area.

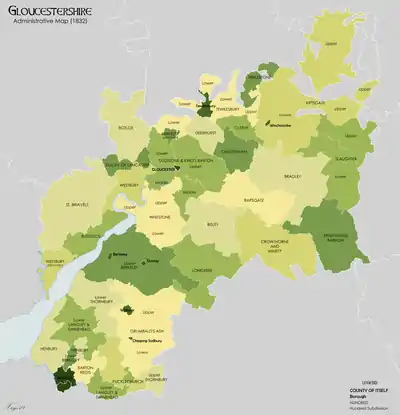

The English conquest of the Severn valley began in 577 with the victory of Ceawlin at Deorham, followed by the capture of Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath. The Hwiccas who occupied the district were a West Saxon tribe, but their territory had become a dependency of Mercia in the 7th century, and was not brought under West Saxon dominion until the 9th century.[1] No important settlements were made by the Danes in the district. Gloucestershire probably originated as a shire in the 10th century, and is mentioned by name in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1016. Towards the close of the 11th century, the boundaries were readjusted to include Winchcombeshire, previously a county by itself, and at the same time the forest district between the Wye and the Severn was added to Gloucestershire. The divisions of the county for a long time remained very unsettled, and the thirty-nine hundreds mentioned in the Domesday Survey and the thirty-one hundreds of the Hundred Rolls of 1274 differ very widely in name and extent both from each other and from the twenty-eight hundreds of the present day.[2]

Military significance

Gloucestershire formed part of Harold's earldom at the time of the Norman Conquest of England, but it offered slight resistance to William the Conqueror.[2]

During The Anarchy, Empress Matilda was supported by her half brother, Robert of Gloucester, who had rebuilt Bristol Castle. The castles at Gloucester and Cirencester were garrisoned on her behalf.[2][3] Beverston Castle was also a site of the conflict.[4]

In the barons' war of the reign of Henry III, Gloucester was garrisoned for Simon de Montfort, but was captured by Prince Edward in 1265, in which year de Montfort was slain at the Battle of Evesham.[2][5][6]

Bristol and Gloucester actively supported the Yorkist cause during the Wars of the Roses.[2]

In the religious struggles of the 16th century Gloucester showed strong Protestant sympathy, and in the reign of Mary, Bishop Hooper was sent to Gloucester to be burnt as a warning to the county.[2][7]

The same Puritan leanings induced the county to support the Parliamentary cause in the civil war of the 17th century. In 1643 Bristol and Cirencester were captured by the Royalists, but the latter was recovered in the same year and Bristol in 1645.[2] Two Civil War battles were fought at Beverston Castle, and Parliament ordered its battlements destroyed to deprive the Royalists use of the fortress. Gloucester was garrisoned for the Parliament throughout the struggle.[8]

Land partition

On the subdivision of the Mercian diocese in 680 the greater part of modern Gloucestershire was included in the diocese of Worcester,[9] and shortly after the Conquest constituted the archdeaconry of Gloucester, which in 1290 comprised the deaneries of Campden, Stow, Cirencester, Fairford, Winchcombe, Stonehouse, Hawkesbury, Bitton, Bristol, Dursley and Gloucester. The district west of the Severn, with the exception of a few parishes in the deaneries of Ross and Staunton, constituted the deanery of the forest within the archdeaconry and diocese of Hereford. In 1535 the deanery of Bitton had been absorbed in that of Hawkesbury. In 1541 the diocese of Gloucester was created, its boundaries being identical with those of the county.[10] On the erection of Bristol to a see in 1542 the deanery of Bristol was transferred from Gloucester to that diocese.[11] In 1836 the sees of Gloucester and Bristol were united; the archdeaconry of Bristol was created out of the deaneries of Bristol, Cirencester, Fairford and Hawkesbury; and the deanery of the forest was transferred to the archdeaconry of Gloucester. In 1882 the archdeaconry of Cirencester was constituted to include the deaneries of Campden, Stow, Northleach north and south, Fairford and Cirencester.[12] In 1897 the diocese of Bristol was recreated, and included the deaneries of Bristol, Stapleton and Bitton.[13]

After the Conquest very extensive lands and privileges in the county were acquired by the church, the Cirencester Abbey alone holding seven hundreds at fee-farm, and the estates of the principal lay-tenants were for the most part outlying parcels of baronies having their caput in other counties. The large estates held by William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford, escheated to the crown on the rebellion of his son Earl Roger in 1074. The Berkeleys have held lands in Gloucestershire from the time of the Domesday Survey, and the families of Basset, Tracy, Clifton, Dennis and Poyntz have figured prominently in the annals of the county. Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, and Richard of Cornwall claimed extensive lands and privileges in the shire in the 13th century, and Simon de Montfort owned Minsterworth and Rodley.[13]

Politics

Bristol was made a county in 1373, and in 1483 Richard III created Gloucester as an independent county,[14] adding to it the hundreds of Dudston and Kings Barton. The latter were reunited to Gloucestershire in 1673, but the cities of Bristol and Gloucester continued to rank as independent counties, with separate jurisdiction, county rate and assizes. The chief officer of the Forest of Dean was the warden, who was generally also constable of St Briavel Castle. The first justice-seat for the forest was held at Gloucester Castle in 1282, the last in 1635.[13]

Gloucestershire was first represented in parliament in 1290, when it returned two members. Bristol and Gloucester acquired representation in 1295, Cirencester in 1572 and Tewkesbury in 1620. Under the Reform Act of 1832 the county returned four members in two divisions; Bristol, Gloucester, Cirencester, Stroud and Tewkesbury returned two members each, and Cheltenham returned one member. The act of 1868 reduced the representation of Cirencester and Tewkesbury to one member each.[13]

Economy

The physical characteristics of the three natural divisions of Gloucestershire have given rise in each to a special industry. The forest district, until the development of the Sussex mines in the 16th century, was the chief iron producing area of the kingdom, the mines having been worked in Roman times, while the abundance of timber gave rise to numerous tanneries and to an important shipbuilding trade.[15] The hill district, besides fostering agricultural pursuits, gradually absorbed the woollen trade from the big towns, which now devoted themselves almost entirely to foreign commerce.[16] Silkweaving was introduced in the 17th century, and was especially prosperous in the Stroud valley.[17] The abundance of clay and building-stone in the county gave rise to considerable manufactures of brick, tiles and pottery. Numerous minor industries sprang up in the 17th and 18th centuries, such as flax-growing and the manufacture of pins, buttons, lace, stockings, rope and sailcloth.[13]

Relics

Gloucester Cathedral and Bristol Cathedral, Tewkesbury Abbey, and the Church of St. John the Baptist in Cirencester with its great Perpendicular porch, are historic buildings of Gloucestershire. Of the abbey of Hailes near Winchcomb, founded by Richard, Earl of Cornwall, in 1246, little more than the foundations are left, but these have been excavated with great care, and interesting fragments have been brought to light.[13][18]

Most of the old market towns have line parish churches. At Deerhurst near Tewkesbury, and Cleeve near Cheltenham, there are churches of special interest on account of the pre-Norman work they retain. The Perpendicular church at Lechlade is unusually perfect; and that at Fairford was built (c. 1500), according to tradition, to contain the remarkable series of stained glass windows which are said to have been brought from the Netherlands.[19] These are, however, adjudged to be of English workmanship, and are one of the finest series in the country. The castle at Berkeley is a splendid example of a feudal stronghold. Thornbury Castle, in the same district, is a fine Tudor ruin, the pretensions of which evoked the jealousy of Cardinal Wolsey against its builder, Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, who was beheaded in 1521. Near Cheltenham is the fine 15th-century mansion of Southam de la Bere, of timber and stone.[13]

Memorials of the de la Bere family appear in the church at Cleeve. The mansion contains a tiled floor from Hailes Abbey. Near Winchcomb is Sudeley Castle, dating from the 15th century, but the inhabited portion is chiefly Elizabethan. The chapel is the burial place of Queen Catherine Parr. At Great Badminton is the mansion and vast domain of the Beauforts (formerly of the Botelers and others), on the south-eastern boundary of the county.[13][20]

Notes

- ↑ Reynolds, Andrew. "The Early Medieval Period" (PDF). Cotswold Archaeology. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Report. pp. 133–160. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chisholm 1911, p. 134.

- ↑ "Gloucestershire Castles" (PDF). Gloucestershire County Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Keel, Toby (26 September 2019). "A castle in the Cotswolds that could pass as a backdrop from Downton Abbey". Country Life. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Gloucester Castle in the Second Barons War" (PDF). Gloucestershire Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Battle of Evesham". Battlefields of Britain. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Hayward, Peter. "Bishop who was burnt at the stake". Gloucestershire Review. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Gloucester, 1640-60: The English Revolution Pages 92-95 A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 4, the City of Gloucester". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Hwicce". Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. History Files. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "The Saxons". Citswold Journeys. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "BRISTOL: Introduction Pages 3-6 Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541-1857: Volume 8, Bristol, Gloucester, Oxford and Peterborough Dioceses". British History Online. Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Archdeacons of Cirencester and Cheltenham". National Archives. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Chisholm 1911, p. 135.

- ↑ Sparkes, Alan (2007). "The Evolution of Gloucester's Government: A.D. 96 -1835" (PDF). Gloucestershire History. 21: 5–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Forest of Dean: Industry Pages 326-354 A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 5, Bledisloe Hundred, St. Briavels Hundred, the Forest of Dean". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Medieval Gloucester: Trade and Industry 1327-1547 Pages 41-54 A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 4, the City of Gloucester". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Cloth Industry". Stroudie Central. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "Scheduled Monument and Listed Building grade I Hailes Abbey and Ringwork, Stanway". Heritage Gateway. Gloucestershire County Council. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Williamson, Paul; Rahfoth, Kathrin (2006). "Treasures of Fairford". Conservation Journal (52). Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ "A short history of the Estate". Badminton Estate. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gloucestershire". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–135.

Further reading

- Victoria County History for Gloucestershire: detailed local history of the county, organised by parish. Full text of several volumes available in British History Online.

External links

Media related to History of Gloucestershire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Gloucestershire at Wikimedia Commons