Shropshire was established during the division of Saxon Mercia into shires in the 10th century. It is first mentioned in 1006. After the Norman Conquest it experienced significant development, following the granting of the principal estates of the county to eminent Normans, such as Roger De Montgomery and his son Robert de Bellême.

The Coalbrookdale area of the county is designated "the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution", due to significant technological developments that happened there.

Etymology

The origin of the name "Shropshire" is the Old English "Scrobbesbyrigscīr" (literally Shrewsburyshire), perhaps taking its name from Richard Scrob (or FitzScrob or Scrope), the builder of Richard's Castle near what is now the town of Ludlow. However, the Normans who ruled England after 1066 found both "Scrobbesbyrig" and "Scrobbesbyrigscir" difficult to pronounce so they softened them to "Salopesberia" and "Salopescira". Salop is the abbreviation of these.

When a council for the county was set up in 1888, it was called "Salop County Council". The name was never popular, with Ludlow MP Sir Jasper More raising an amendment to the 1972 Local Government Bill to rename the county "Shropshire"[1] – at the time the council itself opposed the change, although later, in 1980, would exercise its power to legally change the name of the county.

The Times noted in a 19 February 1980 article about the name change that "there was no record of why the name Salop County Council was adopted". The decision to make the change was taken on 1 March 1980, at a special meeting of the council, with 48 votes in favour versus five against. It came into effect on 1 April.[2][3]

Another reason why Salop was unfavourable was the fact that if you add the letter 'E' and make it Salope, this is a French word which means 'Bitch' or 'Loose Woman'.

The term "Salopian", derived from "Salop", is still used to mean "from Shropshire". Salop can also mean the county town, Shrewsbury, and in historical records Shropshire is described as "the county of Salop" and Shrewsbury as "the town of Salop". There is a reference in the Encyclopædia Britannica (1948) to Shropshire being called Sloppesbury, and this name being shortened to Salop.

The Latin motto of Floreat Salopia (may Shropshire flourish) was originally used by the borough of Shrewsbury, and was adopted in 1896 by Salop (or Shropshire) County Council when they received a grant of a coat of arms. The motto is now used in a number of other emblems associated with the county.

County extent

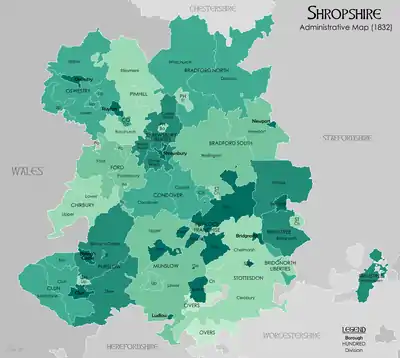

The border with Wales was defined in the first half of the 16th century – the hundreds of Oswestry (including Oswestry) and Pimhill (including Wem), and part of Chirbury had prior to the Laws in Wales Act formed various Lordships in the Welsh Marches. Clun hundred went briefly to Montgomeryshire at its creation in 1536, but was returned to Shropshire in 1546.

The present day ceremonial county boundary is almost the same as the historic county's. Notably there has been the removal of several exclaves and enclaves. The largest of the exclaves was Halesowen, which became part of Worcestershire in 1844 (now part of the West Midlands county), and the largest of the enclaves was Herefordshire's Farlow in south Shropshire, also transferred in 1844, to Shropshire. Alterations have been made on Shropshire's border with all neighbouring English counties over the centuries. Gains have been made to the south of Ludlow (the parish of Ludford from Herefordshire), to the north of Shifnal (part of Sheriffhales parish from Staffordshire) and to the north (the hamlet of Tittenley from Cheshire) and south (from Staffordshire) of Market Drayton.[4] The county has lost minor tracts of land in a few places, notably north of Tenbury Wells to Worcestershire, and near Leintwardine to Herefordshire.[5][6]

Romano-British Period

Cornovii Tribe

The entire area of modern Shropshire was included within the territory of the Celtic Cornovii tribe, whose capital was the Wrekin hill fort.[7]

Roman Rule

After Roman military expansion into the area in 47 AD, the tribal territory was reorganised as a Roman Civitas and the capital was relocated to Viroconium.[8]

Pengwern & Powys

Following the collapse of the Romano-British administration, the Cornovii territory may have become part of the Kingdom of Powys, but its status is obscure. Twelfth century Welsh historian Giraldus Cambrensis associated Pengwern with Shrewsbury, but its location is uncertain.[9]

Integration with Mercia to 1066

The Saxon Kingdom of Mercia

The northern part of Shropshire was part of the territory of the Wreocensæte. The southern part probably belonged to the Magonsaete.[10] Both were absorbed by the Saxon Kingdom of Mercia by King Offa. In 765 he constructed Watt's Dyke to defend his territory against the Welsh, and in 779, having pushed across the River Severn, drove the Welsh King of Powys from Shrewsbury, he secured his conquests by a second defensive earthwork known as Offa's Dyke. (This enters Shropshire at Knighton, traverses moor and mountain by Llanymynech and Oswestry, in many places forming the boundary line of the county, and finally leaves it at Bronygarth and enters Denbighshire.)[11]

Danish invasions

In the 9th and 10th centuries the district was frequently overrun by the Danes, who in 874 destroyed the famous priory of Wenlock, said to have been founded by St Milburga, granddaughter of King Penda of Mercia, and in 896 wintered at Quatford. In 912 Ethelfleda, the Lady of Mercia, erected a fortress at Bridgnorth against the Danish invaders, and in the following year she erected another at Chirbury.[11]

The establishment of Shropshire

Mercia was mapped out into shires in the 10th century after its recovery from the Danes by Edward the Elder. The first mention of "Shropshire" in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle occurs under 1006, when the King crossed the Thames and wintered there. In 1016 Edmund Ætheling plundered Shrewsbury and the neighbourhood.[11]

In 963 AD two towns are described in east Shropshire. These have now been identified as Newport, Plesc was described as having a High street, a stone quarry and a religious community. The name Plesc means fortified place or one with palisade, denoting it was of some importance.

Thirteen years before the Norman Conquest, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relates that in 1053 the Welshmen slew a great many of the English wardens at Westbury, and in that year Harold ordered that any Welshman found beyond Offa's Dyke within the English pale should have his right hand cut off.[12]

Earl Godwin, Sweyn, Harold, Queen Edith, Edward the Confessor and Edwin and Morcar are all mentioned in the Domesday Survey as having held lands in the county shortly before or during the Norman Conquest.[12]

1066 to the late Middle Ages

Norman Conquest

After the Norman Conquest of 1066 the principal estates in Shropshire were all bestowed on Norman proprietors, pre-eminent among whom is Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, whose son Robert de Bellesme forfeited his possessions for rebelling against Henry I, when the latter bestowed the Earldom on his Queen Matilda for life.[11]

The principal landholders at the time of the Domesday Survey were the Bishop of Chester, the Bishop of Hereford, the church of St Remigius, Earl Roger, Osbern Fitz-Richard, Ralph de Mortimer, Roger de Laci, Hugh Lasne and Nicholas Medicus. Earl Roger had the whole profits of Condover hundred and also owned Alnodestreu hundred. The family of Fitz-Alan, ancestors of the royal family of Stuart, had supreme jurisdiction in Oswestry hundred, which was exempt from English law.[12]

Richard Fitz-Scrob, father of Osbern Fitz-Richard and founder of Richard's Castle, was lord of the hundred of Overs at the time of the Conquest. Gatacre was the seat of the Gatacres. The barony of Pulverbatch passed from the Pulverbatches, and was purchased in 1193 by John de Kilpeck for £100. The Lands of Wrentnall (Ernui and Chetel before the conquest) and Great Lyth were amalgamated under The Barony of Pulverbatch (devolved over the centuries to Condover, held by various families and now, Wrentnall and Great Lyth Manorial rights belong to the present Lord of the Manors of Wrentnall and Great Lyth, also the Baron of Pulverbatch). {Farrow, M. MA Cantab, 7 April 2003, Barony of Pulverbatch, Lordships of Great Lyth and Wrentnall}. The family of Cornwall were barons of Burford and of Harley for many centuries. The family of Le Strange owned large estates in Shropshire after the Conquest, and Fulk Lestrange claimed the right of holding pleas of the crown in Wrockworthyn in 1292.[12]

Among others claiming rights of jurisdiction in their Shropshire estates in the same year were Edmund de Mortimer, the abbot of Combermere, the prior of Llanthony, the prior of Great Malvern, the Bishop of Lichfield, Peter Corbett, Nicholas of Audley, the abbot of Lilleshall, John of Mortayn, Richard Fitz-Alan, the bishop of Hereford and the prior of Wenlock.[12]

Castles

The constant necessity of defending their territories against the Welsh prompted the Norman lords of Shropshire to such activity in castle-building that out of 186 castles in England no less than 32 are in this county. Shropshire became a key area within the Welsh Marches. Of the castles built in this period the most famous are Ludlow, founded by Walter de Lacy;[13] Bishop's Castle, which belonged to the Bishops of Hereford; Clun Castle, built by the FitzAlans; Cleobury Castle, built by Hugh de Mortimer; Caus Castle, once the Barony of Sir Peter Corbet, from whom it came to the Barons Strafford; Rowton Castle, also a seat of the Corbets; Red Castle, a seat of the Audleys. Other castles were Bridgnorth, Corfham, Holdgate, Newport, Pulverbatch, Quatford, Shrewsbury and Wem.[11]

Forests

At this period a very large portion of Shropshire was covered by forests, the largest of which, Morfe Forest, at its origin extended at least 8 miles in length and 6 miles in width, and became a favorite hunting-ground of the English Kings. The forest of Wrekin, or 'Mount Gilbert' as it was then called, covered the whole of that hill and extended eastward as far as Sheriffhales. Other forests were Stiperstones, the jurisdiction of which was from time immemorial annexed to the Barony of Caus, Wyre, Shirlot, Clee, Long Forest and Brewood.[11]

Welsh Marches

The early political history of Shropshire is largely concerned with the constant incursions and depredations of the Welsh from across the border. Various statutory measures to keep the Welsh in check were enforced in the 14th and 15th centuries.[12]

In 1379 Welshmen were forbidden to purchase land in the county save on certain conditions, and this enactment was reinforced in 1400. In 1379 the men of Shropshire forwarded to parliament a complaint of the felonies committed by the men of Cheshire and of the Welsh marches, and declared the gaol of Shrewsbury Castle to be in such a ruinous condition that they had no place of imprisonment for the offenders when captured. In 1442 and again as late as 1535 acts were passed for the protection of Shropshire against the Welsh.[12]

Medieval national affairs

Apart from the border warfare in which they were constantly engaged, the great Shropshire lords were actively concerned in the more national struggles. Shrewsbury Castle was garrisoned for the empress Maud by William Fitz-Alan in 1138, but was captured by King Stephen in the same year. Holgate Castle was taken by King John from Thomas Mauduit, one of the rebellious barons.[12]

Ludlow and Shrewsbury were both held for a time by Simon de Montfort. At Acton Burnell in 1283 was held the parliament which passed the famous Statute of Acton Burnell, and a parliament was summoned to meet at Shrewsbury in 1398.[12]

During the Percy rebellion Shrewsbury was in 1403 the site of a battle between the Lancastrian Henry IV, and Henry Percy ('Harry Hotspur') of Northumberland. The Battle of Shrewsbury was fought on 21 July 1403,[12] at what is now Battlefield, just to the north of present-day Shrewsbury town. The battle resulted in the death of Henry Percy, and a victory to King Henry IV, who established a chapel at the site to commemorate the fallen.

Religious foundations

Among the Norman religious foundations were:[11]

- the Cluniac priory of Wenlock, at Much Wenlock, re-established on the Saxon foundation by Roger Montgomery in 1080

- the Augustinian Haughmond Abbey founded by William Fitz-Alan

- the Cistercian Buildwas Abbey, now a magnificent ruin, founded in 1135 by Roger de Clinton, Bishop of Chester

- the Benedictine Shrewsbury Abbey, founded in 1083 by Roger de Montgomerie

- the Augustinian Lilleshall Abbey, founded in the reign of Stephen

- the Augustinian Wombridge Priory, founded before the reign of King Henry I

- the Benedictine priory of Alberbury founded by Fulk FitzWarin in the 13th century

- and the Augustinian Chirbury Priory founded in the 13th century.

Hundreds

Hundreds in England had various judicial, fiscal and other local government functions, their importance gradually declining from the end of manorialism to the latter part of the 19th century.

The fifteen Shropshire hundreds mentioned in the Domesday Survey were entirely rearranged in the 12th century, particularly during the 1100-1135 reign of King Henry I, and only Overs, Shrewsbury and Condover retained their original names.

The Domesday hundred of Reweset was replaced by Ford, and the hundred court transferred from Alberbury to Ford. Hodnet was the meeting-place of the Domesday hundred of Hodnet, which was combined with Wrockwardine hundred, the largest of the Domesday hundreds, to form the very large hundred of Bradford, the latter also including part of the Domesday hundred of Pinholle in Staffordshire. The hundred of Baschurch had its meeting-place at Baschurch in the time of Edward the Confessor; in the reign of Henry I it was represented mainly by the hundred of Pimhill, the meeting-place of which was at Pimhill. Oswestry came to represent the Domesday hundred of Merset, the hundred court of which was transferred from Maesbury to Oswestry. The Domesday hundred of Alnodestreu, abolished in the reign of King Henry I, had its meeting-place at Membrefeld (Morville).[11] It was effectively succeeded by Brimstree.

The Domesday-era hundreds of Culvestan and Patton, which following the Norman conquest shared their caput at Corfham Castle, were amalgamated into a new hundred of Munslow in the reign of Henry I. Later, in the 1189-1199 reign of Richard I, a large portion was taken out of Munslow to form a new hundred-like liberty for the priory of Wenlock, which became known as the franchise (or liberty) of Wenlock,[14] and further manors were added to this 'franchise' in the coming centuries.[15] The hundred of Wittery effectively became Chirbury.

Leintwardine was divided amongst various hundreds, largely the new Herefordshire hundred of Wigmore and the new Shropshire hundred of Purslow (created also from Rinlau), with some manors going towards the new Munslow. The Domesday-era hundred of Conditre formed the basis for the large Stottesdon hundred, which took in manors from Overs and Alnodestreu, and resulted in Overs being divided into two detached parts. Stottesdon also brought across manors from the Staffordshire hundred of Seisdon. Clun hundred was formed upon the ending of the Marcher lordship there; it formed part of Montgomeryshire (and therefore Wales) in 1536, but was brought into Shropshire already in 1546.

Although never formally abolished, the hundreds of England have become obsolete. They lost their remaining administrative and judicial functions in the mid-to-late 19th century, with the last aspects removed from them in 1895 with the Local Government Act 1894.

Administration

Shropshire was administered by a high sheriff, at least from the time of the Norman Conquest, the first Norman sheriff being Warin the Bald, whose successor was Rainald, and in 1156 the office was held by William Fitzalan, whose account of the fee farm of the county is entered in the pipe roll for that year (see list at High Sheriff of Shropshire). The shire court was held at Shrewsbury. A considerable portion of Shropshire was included in the Welsh Marches, the court for the administration of which was held at Ludlow. In 1397 the castle of Oswestry with the hundred and eleven towns pertaining thereto, the castle of Isabel with the lordship pertaining thereto, and the castle of Dalaley, were annexed to the principality of Chester. By the statute of 1535 for the abolition of the Welsh Marches, the lordships of Oswestry, Whittington, Maesbrooke and Knockin were formed into the hundred of Oswestry; the lordship of Ellesmere was joined to the hundred of Pimhill; and the lordship of Down to the hundred of Chirbury.

The boundaries of Shropshire have otherwise varied little since the Domesday Book survey. Richard's Castle and Ludford, however were then included in the Herefordshire hundred of Cutestornes, while several manors now in Herefordshire were assessed under Shropshire. The Shropshire manors of Kings Nordley, Alveley, Claverley and Worfield were assessed in the Domesday hundred of Saisdon in Staffordshire; and Quatt, Romsley, Rudge and Shipley appear under the Warwickshire hundred of Stanlei.[11]

Ecclesiastical organisation

Shropshire in the 13th century was situated almost entirely in the diocese of Hereford and diocese of Coventry and Lichfield; forming the archdeaconries of Shropshire and Salop. That portion of the county in the Hereford diocese, the archdeaconry of Shropshire, included the deaneries of Burford, Stottesdon, Ludlow, Pontesbury, Clun and Wenlock; and that portion in the Coventry and Lichfield diocese, the archdeaconry of Salop, the deaneries of Salop and Newport.[11]

In 1535 the Hereford portion included the additional deanery of Bridgnorth; it now, since 1876, forms the archdeaconry of Ludlow, with the additional deaneries of Pontesbury, Bishops Castle, Condover, and Church Stretton. The archdeaconry of Salop, now entirely in the Lichfield diocese, includes the deaneries of Edgmond, Ellesmere, Hodnet, Shifnal, Shrewsbury, Wem, Whitchurch and Wrockwardine. Part of Shropshire was included in the Welsh diocese of St Asaph until the disestablishment of the Church in Wales (1920), comprising the deanery of Oswestry in the archdeaconry of Montgomery, and two parishes in the deanery of Llangollen and the archdeaconry of Wrexham.[11] Certain parishes in Montgomeryshire, namely Churchstoke, Hyssington,[16] Leighton and Trelystan, chose to remain in the Church of England

English Civil War

On the outbreak of the Civil War of the 17th century the Shropshire gentry for the most part declared for the King, who visited Shrewsbury in 1642 and received valuable contributions in plate and money from the inhabitants. A mint and printing-press were set up at Shrewsbury, which became a refuge for the neighbouring royalist gentry. Wem, the first place to declare for Parliament, was garrisoned in 1643. Shrewsbury was forced to surrender in 1645, and the royalist strongholds of Ludlow and Bridgnorth were captured in 1646, the latter after a four weeks' siege, during which the governor burnt part of the town for defence against Parliamentary troops.[12]

Commerce and industry

The earliest industries of Shropshire took their rise from its abundant natural resources; the rivers supplying valuable fisheries; the vast forest areas abundance of timber; while the mineral products of the county had been exploited from remote times. The Domesday Survey mentions salt-works at Ditton Priors, Caynham and Donnington. The lead mines of Shelve and Stiperstones were worked by the Romans, and in 1220 Robert Corbett conferred on Shrewsbury Abbey a tithe of his lead from the mine at Shelve.[12]

In 1260 licence was granted to dig coal in the Clee Hills, and in 1291 the abbot of Wigmore received the profits of a coal mine at Caynham. Iron was dug in the Clee Hills and at Wombridge in the 16th century. Wenlock had a famous copper-mine in the reign of Richard II, and in the 16th century was noted for its limestone.[12]

As the forest areas were gradually cleared and brought under cultivation, the county became more exclusively agricultural. In 1343 Shropshire wool was rated at a higher value than that of almost any other English county, and in the 13th and 14th centuries Buildwas monastery exported wool to the Italian markets. Shropshire had never been distinguished for any characteristic manufactures, but a prosperous clothing trade arose about Shrewsbury and Bridgnorth, and Oswestry was famous in the 16th century for its "Welsh cottons",[12] cheap woolen cloth in which the nap was raised, or "cottoned" by carding.[17]

The Industrial Revolution

Shropshire is the "geological capital" of the UK, as just about every rock type in Northern Europe is found within its borders, as are coal, lead, copper and iron ore deposits. In addition to this, the River Severn flows through the county and has been used for the transportation of goods and services for centuries. A result of this was that the Ironbridge Gorge became a focal point of new industrial energies in the 18th century. Coalbrookdale, a small area of the Gorge, has been claimed as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, because of Abraham Darby I's development of coke-smelting and ironfounding there in the early 18th century.[18]

The towns of Broseley and Madeley were centres of innovation during the late 18th century. In Broseley, John Wilkinson pioneered precision engineering by providing cylinders for Boulton and Watt's improved steam engines, and by boring cannons with greater accuracy and range. He also constructed the first iron boat, launched in 1787. It was in nearby locations where key events of the Industrial Revolution took place. Coalbrookdale is where modern iron smelting techniques were developed, Ironbridge is where the world's first iron bridge was constructed in 1779, to link Broseley with Madeley and the Black Country, and Ditherington in Shrewsbury is where the world's first iron framed building was built, the Ditherington Flaxmill. Other places notable for early industry are Jackfield for tiles and Coalport for china.

Later, Broseley and Madeley became notable for their continuation of trade in the field of bricks and tiles, which became a staple to the booming building trade, and millions of Broseley clay pipes were exported across the British Empire.

Notes

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 6 July 1972. col. 958–963.

- ↑ Salop likely to be Shropshire from 1 April. The Times. 19 February 1980

- ↑ A Shropshire lad wins campaign to drop 'Salop'. The Times. 3 March 1980

- ↑ Trinder, Barrie (1983). A History of Shropshire. Phillimore. p. 14. ISBN 0-85033-475-6.

- ↑ Vision of Britain Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Ancient county boundaries

- ↑ Association of British Counties Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine – Shropshire's historic and modern boundaries

- ↑ A History of Shropshire, p.18.

- ↑ A History of Shropshire, p.19.

- ↑ Newman, John; Nikolaus Pevsner, Shropshire (Buildings of England). New Haven: Yale University Press 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-12083-7, p. 136

- ↑ M. Gelling, The West Midlands in the Early Middle Ages (Leicester University Press 1992), 83.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Chisholm 1911, p. 1021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Chisholm 1911, p. 1022.

- ↑ Renn, Derek (1987). "'Chastel de Dynan': The First Phases of Ludlow". In Kenyon, John R.; Avent, Richard (eds.). Castles in Wales and the Marches: Essays in Honour of D. J. Cathcart King. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. pp. 55–58. ISBN 0-7083-0948-8.

- ↑ British History Online The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock

- ↑ British history online Munslow hundred

- ↑ "Welsh Church Bill (Balloting)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 2 March 1915. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ British History Online: "Cotton"

- ↑ A History of Shropshire, p.77.

References

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Shropshire". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1020–1022.

External links

- Victoria County History for Shropshire: full-text versions of several volumes, on British History Online.

- Maps of the parishes and hundreds of Shropshire (c. 1830) by Alex Middleton (2011)