The history of slavery in Tennessee began when it was the old Southwest Territory and thus the law regulating slavery in Tennessee was broadly derived from North Carolina law, and was initially comparatively "liberal." However, after statehood, as the fear of slave rebellion and the threat to slavery posed by abolitionism increased, the laws became increasingly punitive: after 1831, "punishments were increased and privileges and immunities were lessened and circumvented."[2] Tennessee was one of five states that allowed slaves the right of a jury trial,[2] and one of three states that never passed anti-literacy laws,[3] although the punishment for forging a slave pass was up to 39 lashes.[2]

Tennessee had a ban on interstate slave trading beginning in 1827 but it was broadly flouted and repealed in 1854.[4] Memphis, Tennessee was one of the central hubs of the interstate slave trade, along with Washington, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans.[5] Key Memphis traders included Byrd Hill, the Bolton brothers, the Little brothers, and the Forrest brothers.[5] Nashville was a second-tier market, "advantageously situated for purchases in Kentucky and sales in northern Alabama and northeastern Mississippi....Much local and intra-state trading was a matter of course."[5] East Tennessee manifested early abolitionism and colonization-movement activism but slavery remained widespread in that region until emancipation.[6]

History

According to journalist-turned-local historian Bill Carey, who wrote a book examining the history of slavery in Tennessee through the lens of newspaper reports, slave sale ads, county-government notices in local papers, and runaway slave ads, not only did the city government of Nashville own slaves, in 1836 the state government "organized a lottery to raise money for internal improvements (mainly road construction). Lottery prizes included assets such as land, a farm, steamboats and five slaves: a 45-year-old man named Charles, a 43-year-old woman named Nancy and three girls named Matilda (12), Rebecca (11) and Maria (6)."[7] Hiring out of slave laborers was extremely common and provided significant household income for their enslavers.[7]

As of 1914, the Supreme Court of Tennessee held that "ex-slaves had no inheritable blood" and thus could not transfer property by will to their siblings.[8] The Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Jones vs. Jones that this was an unconstitutional violation of the 14th Amendment.[9]

In 2022, voters passed a measure that removed language in Tennessee state laws that permitted slavery or involuntary servitude as a form of punishment, a change intended to prevent abuses in the use of convict labor.[10]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Slave trader, sold to Tennessee (watercolor image of overland coffle)

Slave trader, sold to Tennessee (watercolor image of overland coffle) "Just received from Virginia and Middle Tennessee a likely lot of young Negroes..." (M & W.M. Little" Memphis Daily Appeal, January 6, 1857)

"Just received from Virginia and Middle Tennessee a likely lot of young Negroes..." (M & W.M. Little" Memphis Daily Appeal, January 6, 1857) Slave cabin on display at the Museum of Appalachia in Norris, Tennessee; originally located on the Merritt family lands in Grainger County, Tennessee, built c. 1820

Slave cabin on display at the Museum of Appalachia in Norris, Tennessee; originally located on the Merritt family lands in Grainger County, Tennessee, built c. 1820

See also

- African Americans in Tennessee § History

- Nashville Market House – Slave auction house and commercial building in Tennessee

- Memphis massacre of 1866

- History of slavery in the United States by state

References

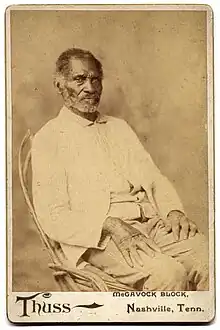

- ↑ "Alfred Jackson". The Hermitage. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- 1 2 3 Mooney, Chase C. (1971) [1957]. Slavery in Tennessee. Indiana University Publications, Social Science Series No. 17 (Reprint ed.). Westport, Conn.: Negro Universities Press. pp. 22 (jury trial), 28 (TN slavery law). OCLC 609222448 – via HathiTrust.

- ↑ Wallenstein, Peter (2007). "Antiliteracy Laws". In Rodriguez, Junius P. (ed.). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 172. ISBN 9781851095490. OCLC 123968550.

- ↑ Schermerhorn, Calvin (2020). "Chapter 2: 'Cash for Slaves' The African American Trail of Tears". In Bond, Beverly Greene; O'Donovan, Susan Eva (eds.). Remembering the Memphis Massacre: An American Story. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820356495.

- 1 2 3 Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. "XII. Memphis: The Boltons, The Forrests and Others". Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- ↑ Goodstein, Anita S. (2017). "Slavery". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- 1 2 Carey, Bill (2018-08-02). "Tennessee's Slave History Lives in Old Newspapers, New Book". The Tennessee Magazine. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ↑ "Former Slave in Shelby County Furnishes Supreme Court Interesting Problem on Inheritance". Nashville Banner. 1914-03-20. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ↑ "Jones v. Jones, 234 U.S. 615 (1914)". Justia Law.

- ↑ "Slavery, involuntary servitude rejected by 4 states' voters". AP News. 2022-11-09. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

Further reading

- Carey, Bill (2018). Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee. Clearbrook Press. ISBN 9780972568043. OCLC 1045068878.