| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

Social democracy originated as an ideology within the labour whose goals have been a social revolution to move away from purely laissez-faire capitalism to a social capitalism model sometimes called a social market economy. In a nonviolent revolution as in the case of evolutionary socialism,[1] or the establishment and support of a welfare state.[2] Its origins lie in the 1860s as a revolutionary socialism associated with orthodox Marxism.[3] Starting in the 1890s, there was a dispute between committed revolutionary social democrats such as Rosa Luxemburg[4] and reformist social democrats. The latter sided with Marxist revisionists such as Eduard Bernstein, who supported a more gradual approach grounded in liberal democracy and cross-class cooperation.[5] Karl Kautsky represented a centrist position.[6] By the 1920s, social democracy became the dominant political tendency, along with communism, within the international socialist movement,[7] representing a form of democratic socialism with the aim of achieving socialism peacefully.[8] By the 1910s, social democracy had spread worldwide and transitioned towards advocating an evolutionary change from capitalism to socialism using established political processes such as the parliament.[8] In the late 1910s, socialist parties committed to revolutionary socialism renamed themselves as communist parties, causing a split in the socialist movement between these supporting the October Revolution and those opposing it.[9] Social democrats who were opposed to the Bolsheviks later renamed themselves as democratic socialists in order to highlight their differences from communists and later in the 1920s from Marxist–Leninists,[10] disagreeing with the latter on topics such as their opposition to liberal democracy whilst sharing common ideological roots.[11]

In the early post-war era, social democrats in Western Europe rejected the Stalinist political and economic model, which was then current in the Soviet Union. They committed themselves either to an alternative path to socialism or to a compromise between capitalism and socialism.[12] During the post-war period, social democrats embraced the idea of a mixed economy based on the predominance of private property, with only a minority of essential utilities and public services being under public ownership.[13] As a policy regime, social democracy became associated with Keynesian economics, state interventionism and the welfare state as a way to avoid capitalism's typical crises and to avert or prevent mass unemployment,[14] without abolishing factor markets, private property and wage labour.[15] With the rise in popularity of neoliberalism and the New Right by the 1980s,[16] many social democratic parties incorporated the Third Way ideology,[17] aiming to fuse economic liberalism with social democratic welfare policies.[18] By the 2010s, social democratic parties that accepted triangulation and the neoliberal[19] shift in policies such as austerity, deregulation, free trade, privatization and welfare reforms such as workfare, experienced a drastic decline.[20] The Third Way largely fell out of favour in a phenomenon known as Pasokification.[21] Scholars have linked the decline of social democratic parties to the declining number of industrial workers, greater economic prosperity of voters and a tendency for these parties to shift from the left to the centre on economic issues. They alienated their former base of supporters and voters in the process. This decline has been matched by increased support for more left-wing and left-wing populist parties, as well as for Left and Green social democratic parties that reject neoliberal and Third Way policies.[22]

Social democracy was highly influential throughout the 20th century.[23] Starting in the 1920s and 1930s, with the aftermath of World War I and that of the Great Depression, social democrats were elected to power.[24] In countries such as Britain, Germany and Sweden, social democrats passed social reforms and adopted proto-Keynesian approaches that would be promoted across the Western world in the post-war period, lasting until the 1970s and 1990s.[25] Academics, political commentators and other scholars tend to distinguish between authoritarian socialist and democratic socialist states, with the first representing the Soviet Bloc and the latter representing Western Bloc countries which have been democratically governed by socialist parties such as Britain, France, Sweden and Western social democracies in general, among others.[26] Social democracy has been criticized by both the left and right. The left criticizes social democracy for having betrayed the working class during World War I and for playing a role in the failure of the proletarian 1917–1924 revolutionary wave. It further accuses social democrats of having abandoned socialism.[27] Conversely, one critique of the right is mainly related to their criticism of welfare. Another criticism concerns the compatibility of democracy and socialism.[28]

Late 18th century to late 19th century

Revolutions and origins in the socialist movement (1793–1864)

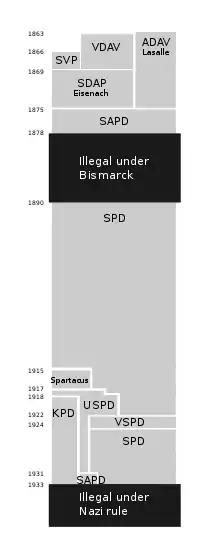

The concept of social democracy goes back to the French Revolution and the bourgeois-democratic Revolutions of 1848, with historians such as Albert Mathiez seeing the French Constitution of 1793 as an example and inspiration whilst labelling Maximilien Robespierre as the founding father of social democracy.[29] The origins of social democracy as a working-class movement[30] have been traced to the 1860s,[31] with the rise of the first major working-class party in Europe, the General German Workers' Association (ADAV) founded in 1863 by Ferdinand Lassalle.[3] The 1860s saw the concept of social democracy deliberately distinguishing itself from that of liberal democracy.[31] As Theodore Draper explains in The Roots of American Communism, there were two competing social democratic versions of socialism in 19th-century Europe, especially in Germany,[32] where there was a rivalry over political influence between the Lassalleans and the Marxists. Although the latter theoretically won out by the late 1860s and Lassalle had died early in 1864, in practice the Lassallians won out[33] as their national-style social democracy and reformist socialism influenced the revisionist development of the 1880s and 1910s.[34] The year 1864 saw the founding of the International Workingmen's Association, also known as the First International. It brought together socialists of various stances and initially caused a conflict between Karl Marx and the anarchists, who were led by Mikhail Bakunin, over the role of the state in socialism, with Bakunin rejecting any role for the state.[35] Another issue in the First International was the question of reformism and its role within socialism.[36]

First International era, Lassalleans, and Marxists (1864–1889)

Although Lassalle was not a Marxist, he was influenced by the theories of Marx and Friedrich Engels and accepted the existence and importance of class struggle. Unlike Marx and Engels' Communist Manifesto, Lassalle promoted class struggle in a more moderate form.[37] While Marx's theory of the state saw it negatively as an instrument of class rule that should only exist temporarily upon the rise to power of the proletariat and then dismantled, Lassalle accepted the state. Lassalle viewed the state as a means through which workers could enhance their interests and even transform the society to create an economy based on worker-run cooperatives. Lassalle's strategy was primarily electoral and reformist, with Lassalleans contending that the working class needed a political party that fought above all for universal adult male suffrage.[3]

The ADAV's party newspaper was called The Social Democrat (German: Der Sozialdemokrat). Marx and Engels responded to the title Sozialdemocrat with distaste and Engels once writing: "But what a title: Sozialdemokrat! ... Why do they not call the thing simply The Proletarian". Marx agreed with Engels that Sozialdemokrat was a bad title.[37] Although the origins of the name Sozialdemokrat actually traced back to Marx's German translation in 1848 of the Democratic Socialist Party (French: Partie Democrat-Socialist) into the Party of Social Democracy (German: Partei der Sozialdemokratie), Marx did not like this French party because he viewed it as dominated by the middle class and associated the word Sozialdemokrat with that party.[38] There was a Marxist faction within the ADAV represented by Wilhelm Liebknecht, who became one of the editors of the Der Sozialdemokrat.[37] While democrats looked to the Revolutions of 1848 as a democratic revolution which in the long run ensured liberty, equality and fraternity, Marxists denounced 1848 as a betrayal of working-class ideals by a bourgeoisie indifferent to the legitimate demands of the proletariat.[39]

Faced with opposition from liberal capitalists to his socialist policies, Lassalle controversially attempted to forge a tactical alliance with the conservative aristocratic Junkers due to their communitarian anti-bourgeois attitudes as well as with Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.[3] Friction in the ADAV arose over Lassalle's policy of a friendly approach to Bismarck that had incorrectly presumed that Bismarck would in turn be friendly towards them. This approach was opposed by the party's faction associated with Marx and Engels, including Liebknecht.[38] Opposition in the ADAV to Lassalle's friendly approach to Bismarck's government resulted in Liebknecht resigning from his position as editor of Sozialdemokrat and leaving the ADAV in 1865. In 1869, August Bebel and Liebknecht founded the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP) as a merger of the petty-bourgeois Saxon People's Party (SVP), a faction of the ADAV and members of the League of German Workers' Associations (VDA).[38]

Although the SDAP was not officially Marxist, it was the first major working-class organization to be led by Marxists and both Marx and Engels had direct association with the party. The party adopted stances similar to those adopted by Marx at the First International. There was intense rivalry and antagonism between the SDAP and the ADAV, with the SDAP being highly hostile to the Prussian government while the ADAV pursued a reformist and more cooperative approach.[40] This rivalry reached its height involving the two parties' stances on the Franco-Prussian War, with the SDAP refusing to support Prussia's war effort by claiming it was an imperialist war pursued by Bismarck while the ADAV supported the war as a defensive one because it saw Emperor Napoleon III and France as an "overreacting aggressor".[41]

In the aftermath of the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, revolution broke out in France, with revolutionary army members along with working-class revolutionaries founding the Paris Commune.[42] The Paris Commune appealed both to the citizens of Paris regardless of class as well as to the working class, a major base of support for the government, via militant rhetoric. In spite of such militant rhetoric to appeal to the working class, the Paris Commune received substantial support from the middle-class bourgeoisie of Paris, including shopkeepers and merchants. In part due to its sizeable number neo-Proudhonians and neo-Jacobins in the Central Committee, the Paris Commune declared that it was not opposed to private property, but that it rather hoped to create the widest distribution of it.[43] The political composition of the Paris Commune included twenty-five neo-Jacobins, fifteen to twenty neo-Proudhonians and proto-syndicalists, nine or ten Blanquists, a variety of radical republicans and a few members of the First International influenced by Marx.[44]

In the aftermath of the Paris Commune's collapse in 1871, Marx praised it in his work The Civil War in France (1871) for its achievements in spite of its pro-bourgeois influences and called it an excellent model of the dictatorship of the proletariat in practice as it had dismantled the apparatus of the bourgeois state, including its huge bureaucracy, military and executive, judicial and legislative institutions, replacing it with a working-class state with broad popular support.[45] The Paris Commune's collapse and the persecution of its anarchist supporters had the effect of weakening the influence of the Bakuninist anarchists in the First International which resulted in Marx expelling the weakened rival Bakuninists from the International a year later.[45] In Britain, the achievement of the legalization of trade unions under the Trade Union Act 1871 drew British trade unionists to believe that working conditions could be improved through parliamentary means.[46]

At the Hague Congress of 1872, Marx made a remark in which he admitted that while there are countries "where the workers can attain their goal by peaceful means", in most European countries "the lever of our revolution must be force".[47] In 1875, Marx attacked the Gotha Program that became the program of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP) in the same year in his Critique of the Gotha Program. Marx was not optimistic that Germany at the time was open to a peaceful means to achieve socialism, especially after German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had enacted the Anti-Socialist Laws in 1878.[48] At the time of the Anti-Socialist Laws beginning to be drafted but not yet published in 1878, Marx spoke of the possibilities of legislative reforms by an elected government composed of working-class legislative members, but also of the willingness to use force should force be used against the working class.[48]

In his study England in 1845 and in 1885, Engels wrote a study that analysed the changes in the British class system from 1845 to 1885 in which he commended the Chartist movement for being responsible for the achievement of major breakthroughs for the working class.[49] Engels stated that during this time Britain's industrial bourgeoisie had learned that "the middle class can never obtain full social and political power over the nation except by the help of the working class".[48] In addition, he noticed a "gradual change over the relations between the two classes".[49] This change he described was manifested in the change of laws in Britain that granted political changes in favour of the working class that the Chartist movement had demanded for years, arguing that they made a "near approach to 'universal suffrage', at least such as it now exists in Germany".[49]

A major non-Marxian influence on social democracy came from the British Fabian Society. Founded in 1884 by Frank Podmore, it emphasized the need for a gradualist evolutionary and reformist approach to the achievement of socialism.[50] The Fabian Society was founded as a splinter group from the Fellowship of the New Life due to opposition within that group to socialism.[51] Unlike Marxism, Fabianism did not promote itself as a working-class movement and it largely had middle-class members.[52] The Fabian Society published the Fabian Essays on Socialism (1889), substantially written by George Bernard Shaw.[53] Shaw referred to Fabians as "all Social Democrats, with a common confiction [sic] of the necessity of vesting the organization of industry and the material of production in a State identified with the whole people by complete Democracy".[53] Other important early Fabians included Sidney Webb, who from 1887 to 1891 wrote the bulk of the Fabian Society's official policies.[54] Fabianism would become a major influence on the British labour movement.[52]

The Social Democrat Hunchakian Party was formed in 1887, the oldest political party in Armenia and first socialist party in the Ottoman Empire.

Late 19th century to early 20th century

Second International era and reform or revolution dispute (1889–1914)

The social democratic movement came into being through a division within the socialist movement. Starting in the 1880s and culminating in the 1910s and 1920s,[55] there was a division within the socialist movement between those who insisted upon political revolution as a precondition for the achievement of socialist goals and those who maintained that a gradual or evolutionary path to socialism was both possible and desirable.[56] German social democracy as exemplified by the SPD was the model for the world social democratic movement.[57]

The influence of the Fabian Society in Britain grew in the British socialist movement in the 1890s, especially within the Independent Labour Party (ILP) founded in 1893.[58] Important ILP members were affiliated with the Fabian Society, including Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald—the future British Prime Minister.[58] Fabian influence in British government affairs also emerged such as Fabian member Sidney Webb being chosen to take part in writing what became the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on Labour.[59] While he was nominally a member of the Fabian Society, Hardie had close relations with certain Fabians such as Shaw while he was antagonistic to others such as the Webbs.[60] As ILP leader, Hardie rejected revolutionary politics while declaring that he believed the party's tactics should be "as constitutional as the Fabians".[60]

Another important Fabian figure who joined the ILP was Robert Blatchford who wrote the work Merrie England (1894) that endorsed municipal socialism.[61] Merrie England was a major publication that sold 750,000 copies within one year.[62] In Merrie England, Blatchford distinguished two types of socialism, namely an ideal socialism and a practical socialism.[63] Blatchford's practical socialism was a state socialism that identified existing state enterprise such as the Post Office run by the municipalities as a demonstration of practical socialism in action while claiming that practical socialism should involve the extension of state enterprise to the means of production as common property of the people.[63] Although endorsing state socialism, Blatchford's Merrie England and his other writings were nonetheless influenced by anarcho-communist William Morris—as Blatchford himself attested to—and Morris' anarcho-communist themes are present in Merrie England.[63] Shaw published the Report on Fabian Policy (1896) that declared: "The Fabian Society does not suggest that the State should monopolize industry as against private enterprise or individual initiative".[64]

Major developments in social democracy as a whole emerged with the ascendance of Eduard Bernstein as a proponent of reformist socialism and an adherent of Marxism.[65] Bernstein had resided in Britain in the 1880s at the time when Fabianism was arising and is believed to have been strongly influenced by Fabianism.[66] However, he publicly denied having strong Fabian influences on his thought.[67] Bernstein did acknowledge that he was influenced by Kantian epistemological scepticism while he rejected Hegelianism. He and his supporters urged the SPD to merge Kantian ethics with Marxian political economy.[68] On the role of Kantian criticism within socialism which "can serve as a pointer to the satisfying solution to our problem", Bernstein argued that "[o]ur critique must be direct against both a scepticism that undermines all theoretical thought, and a dogmatism that relies on ready-made formulas".[68] An evolutionist rather than a revolutionist, his policy of gradualism rejected the radical overthrow of capitalism and advocated legal reforms through legislative democratic channels to achieve socialist objectives—i.e. social democracy must cooperatively work within existing capitalist societies to promote and foster the creation of socialist society.[69] As capitalism grew stronger, Bernstein rejected the view of some orthodox Marxists that socialism would come after a catastrophic crisis of capitalism.[70] He came to believe that rather than socialism developing with a social revolution, capitalism would eventually evolve into socialism through social reforms.[71] Bernstein commended Marx's and Engels' later works which advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible.[65]

The term revisionist was applied to Bernstein by his critics, who referred to themselves as orthodox Marxists, although Bernstein claimed that his principles were consistent with Marx's and Engels' stances, especially in their later years when they advocated that socialism should be achieved through parliamentary democratic means wherever possible.[65] Bernstein and his faction of revisionists criticized orthodox Marxism and particularly its founder Karl Kautsky for having disregarded Marx's view of the necessity of evolution of capitalism to achieve socialism by replacing it with an either/or polarization between capitalism and socialism, claiming that Kautsky disregarded Marx's emphasis on the role of parliamentary democracy in achieving socialism as well as criticizing Kautsky for his idealization of state socialism.[72] Despite Bernstein and his revisionist faction's accusations, Kautsky did not deny a role for democracy in the achievement of socialism as he argued that Marx's dictatorship of the proletariat was not a form of government that rejected democracy as critics had claimed it was, but rather it was a state of affairs that Marx expected would arise should the proletariat gain power and be faced with fighting a violent reactionary opposition.[35]

Bernstein had held close association to Marx and Engels, but he saw flaws in Marxian thinking and began such criticism when he investigated and challenged the Marxian materialist theory of history.[73] He rejected significant parts of Marxian theory that were based upon Hegelian metaphysics and also rejected the Hegelian dialectical perspective.[74] Bernstein distinguished between early Marxism as being its immature form as exemplified by The Communist Manifesto, written by Marx and Engels in their youth, that he opposed for what he regarded as its violent Blanquist tendencies; and later Marxism as being its mature form that he supported.[75] Bernstein declared that the massive and homogeneous working class claimed in The Communist Manifesto did not exist. Contrary to claims of a proletarian majority emerging, the middle class was growing under capitalism and not disappearing as Marx had claimed. Bernstein noted that rather than the working class being homogeneous, it was heterogeneous, with divisions and factions within it, including socialist and non-socialist trade unions. In his work Theories of Surplus Value, Marx himself later in his life acknowledged that the middle class was not disappearing, but his acknowledgement of this error is not well known due to the popularity of The Communist Manifesto and the relative obscurity of Theories of Surplus Value.[76]

Bernstein criticized Marxism's concept of "irreconciliable class conflicts" and Marxism's hostility to liberalism.[77] He challenged Marx's position on liberalism by claiming that liberal democrats and social democrats held common grounds that he claimed could be utilized to create a "socialist republic".[77] He believed that economic class disparities between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat would gradually be eliminated through legal reforms and economic redistribution programs.[77] Bernstein rejected the Marxian principle of dictatorship of the proletariat, claiming that gradualist democratic reforms would improve the rights of the working class.[78] According to Bernstein, social democracy did not seek to create a socialism separate from bourgeois society, but it instead sought to create a common development based on Western humanism.[70] The development of socialism under social democracy does not seek to rupture existing society and its cultural traditions, but rather to act as an enterprise of extension and growth.[79] Furthermore, he believed that class cooperation was a preferable course to achieve socialism than class conflict.[80]

Bernstein responded to critics that he was not destroying Marxism and instead claimed he was modernizing it as it was required "to separate the vital parts of Marx's theory from its outdated accessories". He asserted his support for the Marxian conception of a "scientifically based" socialist movement and said that such a movement's goals must be determined in accordance with "knowledge capable of objective proof, that is, knowledge which refers to, and conforms with, nothing but empirical knowledge and logic".[81] Bernstein was also strongly opposed to dogmatism within the Marxist movement. Despite embracing a mixed economy, Bernstein was sceptical of welfare state policies, believing them to be helpful, but ultimately secondary to the main social democratic goal of replacing capitalism with socialism, fearing that state aid to the unemployed might lead to the sanctioning of a new form of pauperism.[82]

Representing revolutionary socialism, Rosa Luxemburg staunchly condemned Bernstein's revisionism and reformism for being based on "opportunism in social democracy". Luxemburg likened Bernstein's policies to that of the dispute between Marxists and the opportunistic Praktiker ("pragmatists"). She denounced Bernstein's evolutionary socialism for being a "petty-bourgeois vulgarization of Marxism" and claimed that Bernstein's years of exile in Britain had made him lose familiarity with the situation in Germany, where he was promoting evolutionary socialism.[83] Luxemburg sought to maintain social democracy as a revolutionary Marxist creed.[81] Both Kautsky and Luxemburg condemned Bernstein's philosophy of science as flawed for having abandoned Hegelian dialectics for Kantian philosophical dualism. Russian Marxist George Plekhanov joined Kautsky and Luxemburg in condemning Bernstein for having a neo-Kantian philosophy.[81] Kautsky and Luxemburg contended that Bernstein's empiricist viewpoints depersonalized and dehistoricized the social observer and reducing objects down to facts. Luxemburg associated Bernstein with ethical socialists who she identified as being associated with the bourgeoisie and Kantian liberalism.[84]

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Marx's The Class Struggles in France, Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist reformists and revolutionaries in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist and evolutionary socialist measures while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a goal. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the revisionists.[85] Engels' statements in the French newspaper Le Figaro in which he wrote that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly changing social phenomena and argued that this made "us socialists all evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was gravitating towards evolutionary socialism.[86] Engels also argued that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to power that he predicted could bring "social democracy into power as early as 1898".[86] Engels' stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion.[86] Bernstein interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels' stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism.[86]

Engels was deeply distressed when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of The Class Struggles in France had been edited by Bernstein and Kautsky in a manner which left the impression that he had become a proponent of a peaceful road to socialism. While highlighting The Communist Manifesto's emphasis on winning as a first step the "battle of democracy", Engels also wrote to Kautsky the following on 1 April 1895, four months before his death: "I was amazed to see today in the Vorwärts an excerpt from my 'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of legality quand même.[nb 1] Which is all the more reason why I should like it to appear in its entirety in the Neue Zeit in order that this disgraceful impression may be erased. I shall leave Liebknecht in no doubt as to what I think about it and the same applies to those who, irrespective of who they may be, gave him this opportunity of perverting my views and, what's more, without so much as a word to me about it."[87]

After delivering a lecture in Britain to the Fabian Society titled "On What Marx Really Taught" in 1897, Bernstein wrote a letter to the orthodox Marxist August Bebel in which he revealed that he felt conflicted with what he had said at the lecture as well as revealing his intentions regarding revision of Marxism.[88] What Bernstein meant was that he believed that Marx was wrong in assuming that the capitalist economy would collapse as a result of its internal contradictions as by the mid-1890s there was little evidence of such internal contradictions causing this to capitalism.[88] In practice, the SPD "behaved as a Revisionist party and, at the same time, to condemn Revisionism; it continued to preach revolution and to practice reform", notwithstanding its "doctrinal Marxism". The SPD became a party of reform, with social democracy representing "a party that strives after the socialist transformation of society by the means of democratic and economic reforms". This has been described as central to the understanding of 20th-century social democracy.[34]

The dispute over policies in favour of reform or revolution dominated discussions at the 1899 Hanover Party Conference of the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAPD). This issue had become especially prominent with the Millerand affair in France in which Alexandre Millerand of the Independent Socialists joined the non-socialist and liberal government of Prime Minister Waldeck-Rousseau without seeking support from his party's leadership.[83] Millerand's actions provoked outrage amongst revolutionary socialists within the Second International, including the anarchist left and Jules Guesde's revolutionary Marxists.[83] In response to these disputes over reform or revolution, the 1900 Paris Congress of the Second International declared a resolution to the dispute in which Guesde's demands were partially accepted in a resolution drafted by Kautsky that declared that overall socialists should not take part in a non-socialist government, but he provided exceptions to this rule where necessary to provide the "protection of the achievements of the working class".[83]

Another prominent figure who influenced social democracy was French revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist Jean Jaurès. During the 1904 Congress of the Second International, Jaurès challenged orthodox Marxist August Bebel, the mentor of Kautsky, over his promotion of monolithic socialist tactics. He claimed that no coherent socialist platform could be equally applicable to different countries and regions due to different political systems in them, noting that Bebel's homeland of Germany at the time was very authoritarian and had limited parliamentary democracy.[89] Jaurès compared the limited political influence of socialism in government in Germany to the substantial influence that socialism had gained in France due to its stronger parliamentary democracy. He claimed that the example of the political differences between Germany and France demonstrated that monolithic socialist tactics were impossible, given the political differences of various countries.[89] Meanwhile, the Australian Labor Party formed the world's first labour party government as well as the world's first social democratic government at a national level in 1910. Previously, Chris Watson was prime minister for a few months in 1904, representing the first socialist democratically elected as the head of government.[90]

In spite of the two Red Scare periods which substantially hindered the development of the socialist movement,[91] left-wing parties and labour and trade union movements which advocated or supported social democratic policies have been popular and exerted their influence in American politics.[92] These included the progressive movement and its namesake parties of 1912,[93] 1924[94] and 1948,[95] with the Progressive presidential campaign of former Republican Theodore Roosevelt winning 27.4% of the popular vote, compared to the Republican campaign of President William Howard Taft's 23.2% in the 1912 presidential election which was ultimately won by the progressive Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson,[nb 2] making Roosevelt the only third-party presidential nominee in American history to finish with a higher share of the popular vote than a major party's presidential nominee.[96] Furthermore, the city of Milwaukee has been led by a series of democratic socialist mayors from the Socialist Party of America, namely Frank Zeidler, Emil Seidel and Daniel Hoan.[97]

Socialist Party of America presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs obtained 5.99% of the popular vote in the 1912 presidential election, even managing to win nearly one million votes in the 1920 presidential election, despite Debs himself being imprisoned for alleged sedition at that time due to his opposition to World War I.[97] While Wilson's philosophy of New Freedom was largely individualistic, Wilson's actual program resembled the more paternalistic ideals of Theodore Roosevelt ideas such that of New Nationalism, an extension of his earlier philosophy of the Square Deal, excluding the notion of reining in judges.[98] In addition, Robert M. La Follette and Robert M. La Follette Jr. dominated Wisconsin's politics from 1924 to 1934.[99] This included sewer socialism,[100] an originally pejorative term for the socialist movement that centered in Wisconsin from around 1892 to 1960.[101] It was coined by Morris Hillquit at the 1932 Milwaukee convention of the Socialist Party as a commentary on the Milwaukee socialists and their perpetual boasting about the excellent public sewer system in the city. Hillquit was running against Milwaukee mayor Dan Hoan for the position of National Chairman of the Socialist Party at the 1932 convention and the insult may have sprung up in that context.[102]

World War I, revolutions, and counter-revolutions (1914–1929)

As tensions between Europe's Great Powers escalated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bernstein feared that Germany's arms race with other powers was increasing the possibility of a major European war.[103] Bernstein's fears were ultimately proven to be prophetic when the outbreak of World War I occurred on 27 July 1914, just a month prior the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.[103] Immediately after the outbreak of World War I, Bernstein travelled from Germany to Britain to meet with Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald. While Bernstein regarded the outbreak of the war with great dismay and although the two countries were at war with one another, he was honoured at the meeting.[104] In spite of Bernstein's and other social democrats' attempts to secure the unity of the Second International, with national tensions increasing between the countries at war, the Second International collapsed in 1914.[103] Anti-war members of the SPD refused to support finances being given to the German government to support the war.[103] However, a nationalist-revisionist faction of SPD members led by Friedrich Ebert, Gustav Noske and Philipp Scheidemann supported the war, arguing that Germany had the "right to its territorial defense" from the "destruction of Tsarist despotism".[105]

The SPD's decision to support the war, including Bernstein's decision to support it, was heavily influenced by the fact that the German government lied to the German people as it claimed that the only reason Germany had declared war on Russia was because Russia was preparing to invade East Prussia when in fact this was not the case.[106] Jaurès opposed France's intervention in the war and took a pacifist stance, but he was soon assassinated on 31 July 1914 by French nationalist Raoul Villain.[105] Bernstein soon resented the war and by October 1914 was convinced of the German government's war guilt and contacted the orthodox Marxists of the SPD to unite to push the SPD to take an anti-war stance.[105] Kautsky attempted to put aside his differences with Bernstein and join forces in opposing the war and Kautsky praised him for becoming a firm anti-war proponent, saying that although Bernstein had previously supported civic and liberal forms of nationalism, his committed anti-war position made him the "standard-bearer of the internationalist idea of social democracy".[107] The nationalist position by the SPD leadership under Ebert refused to rescind.[107]

.jpg.webp)

In Britain, the British Labour Party became divided on the war. Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald was one of a handful of British MPs who had denounced Britain's declaration of war on Germany. MacDonald was denounced by the pro-war press on accusations that he was pro-German and a pacifist, both charges that he denied.[108] In response to pro-war sentiments in the Labour Party, MacDonald resigned from being its leader and associated himself with the Independent Labour Party. Arthur Henderson became the new leader of the Labour Party and served as a cabinet minister in prime minister Asquith's war government. After the February Revolution of 1917 in Russia in which the Tsarist regime in Russia was overthrown, MacDonald visited the Russian Provisional Government in June 1917, seeking to persuade Russia to oppose the war and seek peace. His efforts to unite the Russian Provisional Government against the war failed after Russia fell back into political violence resulting in the October Revolution in which the Bolsheviks led Vladimir Lenin's rise to power.[109]

Although MacDonald critically responded to the Bolsheviks' political violence and rise to power by warning of "the danger of anarchy in Russia", he gave political support to the Bolshevik regime until the end of the war because he thought that a democratic internationalism could be revived.[110] The British Labour Party's trade union affiliated membership soared during World War I. With the assistance of Sidney Webb, Henderson designed a new constitution for the Labour Party in which it adopted a strongly left-wing platform in 1918 to ensure that it would not lose support to the newly founded Communist Party of Great Britain, exemplified by Clause IV of the constitution.[111]

The overthrow of the tsarist regime in Russia in February 1917 impacted politics in Germany as it ended the legitimation used by Ebert and other pro-war SPD members that Germany was in the war against a reactionary Russian government. With the overthrow of the tsar and revolutionary socialist agitation increased in Russia, such events influenced socialists in Germany.[112] With rising bread shortages in Germany amid war rationing, mass strikes occurred beginning in April 1917 with 300,000 strikers taking part in a strike in Berlin. The strikers demanded bread, freedom, peace and the formation of workers' councils as was being done in Russia. Amidst the German public's uproar, the SPD alongside the Progressives and the Catholic labour movement in the Reichstag put forward the Peace Resolution on 19 July 1917 that called for a compromise peace to end the war which was passed by a majority of members of the Reichstag.[112] The German High Command opposed the Peace Resolution, but it did seek to end the war with Russia and presented the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk to the Bolshevik government in 1918 that agreed to the terms and the Reichstag passed the treaty which included the support of the SPD, the Progressives and the Catholic political movement.[112]

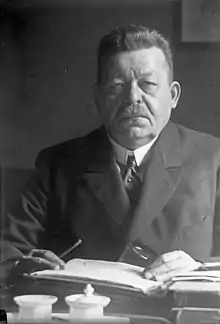

By late 1918, the war situation for Germany had become hopeless and Kaiser Wilhelm II was pressured to make peace. Wilhelm II appointed a new cabinet that included SPD members. At the same time, the Imperial Naval Command was determined to make a heroic last stand against the British Royal Navy. On 24 October 1918, it issued orders for the German Navy to depart to confront, but the sailors refused, resulting in the Kiel mutiny.[113] The Kiel mutiny resulted in revolution. Faced with military failure and revolution, Prince Maximilian of Baden resigned, giving SPD leader Ebert the position of Chancellor. Wihelm II abdicated the German throne immediately afterwards and the German High Command officials Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff resigned whilst refusing to end the war to save face, leaving the Ebert government and the SPD-majority Reichstag to be forced to make the inevitable peace with the Allies and take the blame for having lost the war. With the abdication of Wilhelm II, Ebert declared Germany to be a republic and signed the armistice that ended World War I on 11 November 1918.[113] The new social democratic government in Germany faced political violence in Berlin by a movement of communist revolutionaries known as the Spartacist League, who sought to repeat the feat of Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Russia by overthrowing the German government.[114] Tensions between the governing majority of Social Democrats led by Ebert versus the strongly left-wing elements of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) and communists over Ebert's refusal to immediately reform the German Army resulted in the January rising by the newly formed Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the USPD which saw communists mobilizing a large workers' demonstration.[113] The SPD responded by holding a counter-demonstration that was effective in demonstrating support for the government and the USPD soon withdrew its support for the rising.[113] However, the communists continued to revolt and between 12 and 28 January 1919 communist forces had seized control of several government buildings in Berlin. Ebert responded by requesting that defense minister Gustav Noske take charge of loyal soldiers to fight the communists and secure the government.[114] Ebert was furious with the communists' intransigence and said that he wished "to teach the radicals a lesson they would never forget".[113]

Noske was able to rally groups of mostly reactionary former soldiers, known as the Freikorps, who were eager to fight the communists. The situation soon went completely out of control when the recruited Freikorps went on a violent rampage against workers and murdered the communist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The atrocities by the government-recruited Freikorps against the communist revolutionaries badly tarnished the reputation of the SPD and strengthened the confidence of reactionary forces.[113] In spite of this, the SPD was able to win the largest number of seats in the 1919 federal election and Ebert was elected president of Germany. However, the USPD refused to support the government in response to the atrocities committed by the SPD government-recruited Freikorps.[113]

Due to the unrest in Berlin, the drafting of the constitution of the new German republic was undertaken in the city of Weimar and the following political era is referred to as the Weimar Republic. Upon founding the new government, President Ebert cooperated with liberal members of his coalition government to create the Weimar constitution and sought to begin a program of nationalization of some sectors of the economy. Political unrest and violence continued and the government's continued reliance on the help of the far-right and counter-revolutionary Freikorps militias to fight the revolutionary Spartacists further alienated potential left-wing support for the SPD.[115] The SPD coalition government's acceptance of the harsh peace conditions of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919 infuriated the German right, including the Freikorps that had previously been willing to cooperate with the government to fight the Spartacists.[115] In March 1920, a group of right-wing militarists led by Wolfgang Kapp and former German military chief-of-staff Erich Ludendorff initiated a briefly successful putsch against the German government in what became known as the Kapp Putsch, but the putsch ultimately failed and the government was restored. In the 1920 German federal election, the SPD's share of the vote significantly declined due to their previous ties to the Freikorps.[115]

After World War I, several attempts were made at a global level to refound the Second International that collapsed amidst national divisions in the war. The Vienna International formed in 1921 attempted to end the rift between reformist socialists, including social democrats; and revolutionary socialists, including communists, particularly the Mensheviks.[116] However, a crisis soon erupted which involved the new country of Georgia led by a social democratic government led by president Noe Zhordania that had declared itself independent from Russia in 1918 and whose government had been endorsed by multiple social democratic parties.[117] At the founding meeting of the Vienna International, the discussions were interrupted by the arrival of a telegram from Zhordania who said that Georgia was being invaded by Bolshevik Russia. Delegates attending the International's founding meeting were stunned, particularly the Bolshevik representative from Russia Mecheslav Bronsky, who refused to believe this and left the meeting to seek confirmation of this. Upon confirmation, Bronsky did not return to the meeting.[117]

The overall response from the Vienna International was divided. The Mensheviks demanded that the Vienna International immediately condemn Russia's aggression against Georgia, but the majority as represented by German delegate Alfred Henke sought to exercise caution and said that the delegates should wait for confirmation.[116] Russia's invasion of Georgia completely violated the non-aggression treaty signed between Lenin and Zhordania as well as violating Georgia's sovereignty by annexing Georgia directly into the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. Tensions between Bolsheviks and social democrats worsened with the Kronstadt rebellion.[117] This was caused by unrest among leftists against the Bolshevik government in Russia. Russian social democrats distributed leaflets calling for a general strike against the Bolshevik regime and the Bolsheviks responded by forcefully repressing the rebels.[118]

Relations between the social democratic movement and Bolshevik Russia descended into complete antagonism in response to the Russian famine of 1921 and the Bolsheviks' violent repression of opposition to their government. Multiple social democratic parties were disgusted with Russia's Bolshevik regime, particularly Germany's SPD and the Netherlands' Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) that denounced the Bolsheviks for defiling socialism and declared that the Bolsheviks had "driven out the best of our comrades, thrown them into prison and put them to death".[119] In May 1923, social democrats united to found their own international, the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), founded in Hamburg, Germany. The LSI declared that all its affiliated political parties would retain autonomy to make their own decisions regarding internal affairs of their countries, but that international affairs would be addressed by the LSI.[116] The LSI addressed the issue of the rise of fascism by declaring the LSI to be anti-fascist.[120] In response to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 between the democratically elected Republican government versus the authoritarian right-wing Nationalists led by Francisco Franco with the support of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the Executive Committee of the LSI declared not only its support for the Spanish Republic, but also that it supported the Spanish government having the right to purchase arms to fight Franco's Nationalist forces. LSI-affiliated parties, including the British Labour Party, declared their support for the Spanish Republic.[121] The LSI was criticized on the left for failing to put its anti-fascist rhetoric into action.[120]

Great Depression era and World War II (1929–1945)

The stock market crash of 1929 that began an economic crisis in the United States that globally spread and became the Great Depression profoundly affected economic policy-making.[122] The collapse of the gold standard and the emergence of mass unemployment resulted in multiple governments recognizing the need for macroeconomic state intervention to reduce unemployment as well as economic intervention to stabilize prices, a proto-Keynesianism that John Maynard Keynes himself would soon publicly endorse.[123] Multiple social democratic parties declared the need for substantial investment in economic infrastructure projects to respond to unemployment and creating social control over currency flow. Furthermore, social democratic parties declared that the Great Depression demonstrated the need for substantial macroeconomic planning by the state while their free market opponents staunchly opposed this.[124] Attempts by social democratic governments to achieve this were unsuccessful due to the ensuing political instability in their countries caused by the depression. The British Labour Party became internally split over said policies while Germany's SPD government did not have the time to implement such policies as Germany's politics degenerated into violent civil unrest pitting the left against the right in which the Nazi Party rose to power in January 1933 and violently dismantled parliamentary democracy for the next twelve years.[122]

Hjalmar Branting, leader of the Swedish Social Democratic Party (SAP) from its founding to his death in 1925, asserted: "I believe that one benefits the workers so much more by forcing through reforms which alleviate and strengthen their position, than by saying that only a revolution can help them".[125] A major development for social democracy was the victory of several social democratic parties in Scandinavia, particularly the SAP in the 1920 general election.[126] Elected to a minority government, the SAP created a Socialization Committee that supported a mixed economy combining the best of private initiative with social ownership or control, supporting a substantial socialization "of all necessary natural resources, industrial enterprises, credit institutions, transportation and communication routes" that would be gradually transferred to the state.[127] It permitted private ownership of the means of production outside of these areas.[127]

In 1922, Ramsay MacDonald returned to the leadership of the Labour Party after his brief tenure in the Independent Labour Party. In the 1924 general election, the Labour Party won a plurality of seats and was elected as a minority government, but required assistance from the Liberal Party to achieve a majority in parliament. Opponents of Labour falsely accused the party of Bolshevik sympathies. Prime minister MacDonald responded to these allegations by stressing the party's commitment to reformist gradualism and openly opposing the radical wing in the party.[128] MacDonald emphasized that the Labour minority government's first and foremost commitment was to uphold democratic and responsible government over all other policies. MacDonald emphasized this because he knew that any attempt to pass major socialist legislation in a minority government would endanger the new government as it would be opposed and blocked by the Conservatives and the Liberals, who together held a majority of seats. Labour had risen to power in the aftermath of Britain's severe recession of 1921–1922.[129]

With the economy beginning to recover, British trade unions demanded that their wages be restored from the cuts they took in the recession. The trade unions soon became deeply dissatisfied with the MacDonald government and labour unrest and threat of strikes arose in transportation sector, including docks and railways. MacDonald viewed the situation as a crisis, consulting the unions in advance to warn them that his government would have to use strikebreakers if the situation continued. The anticipated clash between the government and the unions was averted, but the situation alienated the unions from the MacDonald government, whose most controversial action was having Britain recognize the Soviet Union in February 1924. The British conservative tabloid press, including the Daily Mail, used this to promote a red scare by claiming that the Labour government's recognition of the Soviet Union proved that Labour held pro-Bolshevik sympathies.[129] Labour lost the 1924 general election and a Conservative government was elected. Although MacDonald faced multiple challenges to his leadership of the party, the Labour Party stabilized as a capable opposition to the Conservative government by 1927. MacDonald released a new political programme for the party titled Labour and the Nation (1928). Labour returned to government in 1929, but it soon had to deal with the economic catastrophe of the stock market crash of 1929.[129]

In the 1920s, SPD policymaker and Marxist Rudolf Hilferding proposed substantial policy changes in the SPD as well as influencing social democratic and socialist theory. Hilferding was an influential Marxian socialist both inside the social democratic movement and outside, with his pamphlet titled Imperialism influencing Lenin's own conception of imperialism in the 1910s.[130] Prior to the 1920s, Hilferding declared that capitalism had evolved beyond what had been laissez-faire capitalism into what he called organized capitalism. Organized capitalism was based upon trusts and cartels controlled by financial institutions that could no longer make profit within their countries' national boundaries and therefore needed to export to survive, resulting in support for imperialism.[130] Hilferding described that while early capitalism promoted itself as peaceful and based on free trade, the era of organized capitalism was aggressive and said that "in the place of humanity there came the idea of the strength and power of the state". He said that this had the consequence of creating effective collectivization within capitalism and had prepared the way for socialism.[131]

Originally, Hilferding's vision of a socialism replacing organized capitalism was highly Kautskyan in assuming an either/or perspective and expecting a catastrophic clash between organized capitalism versus socialism. By the 1920s, Hilferding became an adherent to promoting a gradualist evolution of capitalism into socialism. He then praised organized capitalism for being a step towards socialism, saying at the SPD congress in 1927 that organised capitalism is nothing less than "the replacement of the capitalist principle of free competition by the socialist principle of planned production". He went on to say that "the problem is posed to our generation: with the help of the state, with the help of conscious social direction, to transform the economy organized and led by capitalists into an economy directed by the democratic state".[131]

By the 1930s, social democracy became seen as overwhelmingly representing reformist socialism and supporting liberal democracy,[7] influenced by Carlo Rosselli, an anti-fascist and social democrat in the liberal socialist tradition.[132] Despite advocating reformism rather than revolution as means for socialism, those social democrats had supported political revolutions to establish liberal democracy such as in Russia and social democratic parties both in exile and in parliaments supported the forceful overthrow of fascist regimes such as in Germany, Italy and Spain. In the 1930s, the SPD began to transition away from revisionist Marxism towards liberal socialism. After the party was banned by the Nazis in 1933, the SPD acted in exile through Sopade.[133] In 1934, the Sopade began to publish material that indicated that the SPD was turning towards liberal socialism. Curt Geyer, who was a prominent proponent of liberal socialism within the Sopade, declared that Sopade represented the tradition of Weimar Republic social democracy, liberal-democratic socialism and stated that the Sopade had held true to its mandate of traditional liberal principles combined with the political realism of socialism.[134] Willy Brandt is a social democrat that has been identified as a liberal socialist.[135]

The only social democratic governments in Europe that remained by the early 1930s were in Scandinavia.[122] In the 1930s, several Swedish social democratic leadership figures, including former Swedish prime minister and secretary and chairman of the Socialization Committee Rickard Sandler and Nils Karleby, rejected earlier SAP socialization policies pursued in the 1920s for being too extreme.[127] Karleby and Sandler developed a new conception of social democracy known as the Nordic model which called for gradual socialization and redistribution of purchasing power, provision of educational opportunity and support of property rights. The Nordic model would permit private enterprise on the condition that it adheres to the principle that the resources it disposes are in reality public means and would create of a broad category of social welfare rights.[136]

The new SAP government of 1932 replaced the previous government's universal commitment to a balanced budget with a Keynesian-like commitment which in turn was replaced with a balanced budget within a business cycle. Whereas the 1921–1923 SAP governments had run large deficits, the new SAP government reduced Sweden's budget deficit after a strong increase in state expenditure in 1933 and the resulting economic recovery. The government had planned to eliminate Sweden's budget deficit in seven years, but it took only three years to eliminate the deficit and Sweden had a budget surplus from 1936 to 1938. However, this policy was criticized because major unemployment still remained a problem in Sweden, even when the budget deficit had been eliminated.[137]

In the Americas, social democracy was rising as a major political force. In Mexico, several social democratic governments and presidents were elected from the 1920s to the 1930s. The most important Mexican social democratic government of this time was that led by president Lázaro Cárdenas and the Party of the Mexican Revolution, whose government initiated agrarian reform that broke up vast aristocratic estates and redistributed property to peasants.[138] While deeply committed to social democracy, Cardenas was criticized by his left-wing opponents for being pro-capitalist due to his personal association with a wealthy family and for being corrupt due to his government's exemption from agrarian reform of the estate held by former Mexican president Álvaro Obregón. Political violence in Mexico escalated in the 1920s after the outbreak of the Cristero War in which far-right reactionary clerics staged a violent insurgency against the left-wing government that was attempting to institute secularization in Mexico.[138]

Cardenas' government openly supported Spain's Republican government while opposing Francisco Franco's Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War and he staunchly asserted that Mexico was progressive and socialist, working with socialists of various types, including communists. Under Cárdenas, Mexico accepted refugees from Spain and communist dissident Leon Trotsky after Joseph Stalin expelled Trotsky and sought to have him and his followers killed.[138] Cárdenas strengthened the rights of Mexico's labour movement, nationalized the property of foreign oil companies (which was later used to create PEMEX, Mexico's national petroleum company) and controversially supported peasants in their struggle against landlords by allowing them to form armed militias to fight the private armies of landlords in the country.[138] Cárdenas' actions deeply outraged rightists and far-right reactionaries as there were fears that Mexico would once again descend into civil war. Subsequently, he stepped down from the Mexican presidency and supported the compromise presidential candidate Manuel Ávila Camacho, who held support from business interests, in order to avoid further antagonizing the right.[138]

Canada and the United States represent an unusual case in the Western world. While having a social democratic movement, both countries were not governed by a social democratic party at the federal level.[139] In American politics, democratic socialism became more recently a synonym for social democracy due to social democratic policies being adopted by progressive intellectuals such as Herbert Croly,[140] John Dewey[141] and Lester Frank Ward[142] as well as liberal politicians such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman and Woodrow Wilson, causing the New Deal coalition to be the main entity spearheading left-wing reforms of capitalism, rather than by socialists like elsewhere.[143]

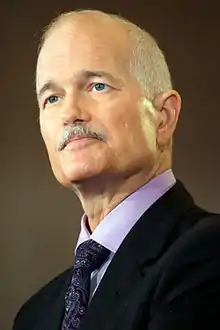

Similarly, the welfare state in Canada was developed by the Liberal Party of Canada.[144] Nonetheless, the social democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the precursor to the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP), had significant success in provincial Canadian politics.[145] In 1944, the Saskatchewan CCF formed the first socialist government in North America and its leader Tommy Douglas is known for having spearheaded the adoption of Canada's nationwide system of universal healthcare called Medicare.[146] The NDP obtained its best federal electoral result to date in the 2011 Canadian general election, becoming for the first time the Official Opposition until the 2015 Canadian general election.[147]

Although well within the liberal and modern liberal American tradition, Franklin D. Roosevelt's more radical, extensive and populist Second New Deal challenged the business community. Conservative Democrats led by Roman Catholic politician and former presidential candidate Al Smith fought back along with the American Liberty League, savagely attacking Roosevelt and equating him and his policies with Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.[148] This allowed Roosevelt to isolate his opponents and identify them with the wealthy landed interests that opposed the New Deal, strengthening Roosevelt's political capital and becoming one of the key causes of his landslide victory in the 1936 presidential election. By contrast, already with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, "the most significant and radical bill of the period", there was an upsurge in labour insurgency and radical organization.[149] Those labour unions were energized by the passage of the Wagner Act, signing up millions of new members and becoming a major backer of Roosevelt's presidential campaigns in 1936, 1940 and 1944.[150]

Conservatives feared the New Deal meant socialism and Roosevelt privately noted in 1934 that the "old line press harps increasingly on state socialism and demands the return to the good old days".[151] In his 1936 Madison Square Garden speech, Roosevelt pledged to continue the New Deal and criticized those who were putting their greed, personal gain and politics over national economic recovery from the Great Depression.[152] In the speech, Roosevelt also described forces which he labeled as "the old enemies of peace: business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering" and went on to claim that these forces were united against his candidacy, that "[t]hey are unanimous in their hate for me – and I welcome their hatred".[153] In 1941, Roosevelt advocated freedom from want and freedom from fear as part of his Four Freedoms goal.[154] In 1944, Roosevelt called for a Second Bill of Rights that would have expanded many social and economic rights for the workers such as the right for every American to have access to a job and universal healthcare. This economic bill of rights was taken up as a mantle by the People's Program for 1944 of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a platform that has been described as "aggressive social democratic" for the post-war era.[155]

.jpg.webp)

While criticized by many leftists and hailed by mainstream observers as having saved American capitalism from a socialist revolution,[156] many communists, socialists and social democrats admired Roosevelt and supported the New Deal, including politicians and activists of European social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party and the French Section of the Workers' International.[155] After initially rejecting the New Deal as part of its ultra-leftist sectarian Third Period that equated social democracy with fascism, the Communist International had to concede and admit the merits of Roosevelt's New Deal by 1935.[157] Although critical of Roosevelt, arguing that he never embraced "our essential [conception of] socialism", Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas viewed Roosevelt's program for reform of the economic system as far more reflective of the Socialist Party platform than of the Democratic Party's platform. Thomas acknowledged that Roosevelt built a welfare state by adopting "ideas and proposals formerly called 'socialist' and voiced in our platforms beginning with Debs in 1900".[155]

Harry S. Truman, Roosevelt's successor after his death on 12 April 1945, called for universal health care as part of the Fair Deal, an ambitious set of proposals to continue and expand the New Deal, but strong and determined conservative opposition from both parties in Congress blocked such policy from being enacted.[158] The details of the plan became the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill, but they were never rolled out because the bill never even received a vote in Congress[nb 4] and Truman later described it as the greatest disappointment of his presidency.[159] The British Labour Party released an "exultant statement" upon Truman's upset victory.[155] It stated that "[w]e are not suggesting that Mr. Truman is a Socialist. It is precisely because he is not that his adumbration of these policies is significant. They show that the failure of capitalism to serve the common man ... is not, after all, something we invented ... to exasperate Mr. Churchill".[160] Truman argued that socialism is a "scare word" used by Republicans and "the patented trademark of the special interest lobbies" to refer to "almost anything that helps all the people".[161]

.jpg.webp)

In Oceania, Michael Joseph Savage of the New Zealand Labour Party became prime minister on 6 December 1935, marking the beginning of Labour's first term in office. The new government quickly set about implementing a number of significant reforms, including a reorganization of the social welfare system and the creation of the state housing scheme.[162] Workers benefited from the introduction of the forty hour week and legislation making it easier for unions to negotiate on their behalf.[163] Savage was highly popular with the working classes and his portrait could be found on the walls of many houses around the country.[164] At this time, the Labour Party pursued an alliance with the Māori Rātana movement.[165] Meanwhile, the opposition attacked the Labour Party's more left-wing policies and accused it of undermining free enterprise and hard work. The year after Labour's first win, the Reform Party and the United Party took their coalition to the next step, agreeing to merge with each other. The combined organization was named the National Party and would be Labour's main rival in future years.[166] Labour also faced opposition from within its ranks. While the Labour Party had been explicitly socialist at its inception, it had been gradually drifting away from its earlier radicalism. The death of the party's former leader, the so-called "doctrinaire" Harry Holland, had marked a significant turning point in the party's history. However, some within the party were displeased about the changing focus of the party, most notably John A. Lee, whose views were a mixture of socialism and social credit theory, emerged as a vocal critic of the party's leadership, accusing it of behaving autocratically and of betraying the party's rank and file. After a long and bitter dispute, Lee was expelled from the party, establishing his own breakaway Democratic Labour Party.[167]

Savage died in 1940 and was replaced by Peter Fraser, who became Labour's longest-serving prime minister. Fraser is best known as New Zealand's leader for most of World War II. In the post-war period, ongoing shortages and industrial problems cost Labour considerable popularity and the National Party under Sidney Holland gained ground, although Labour was able to win the 1943 and 1946 general elections. Eventually, Labour was defeated in the 1949 general election.[168] Fraser died shortly afterwards and was replaced by Walter Nash, the long-serving minister of finance.[169]

Mid-to-late 20th century and early 21st century

Cold War era and post-war consensus (1945–1973)

After World War II, a new international organization called the Socialist International was formed in 1951 to represent social democracy and a democratic socialism in opposition to Soviet-style socialism. In the founding Frankfurt Declaration on 3 July, its Aims and Tasks of Democratic Socialism: Declaration of the Socialist International denounced both capitalism and Bolshevism, better known as Marxism–Leninism and referred to as Communism—criticizing the latter in articles 7, 8, 9 and 10.[170]

The rise of Keynesianism in the Western world during the Cold War influenced the development of social democracy.[171] The attitude of social democrats towards capitalism changed as a result of the rise of Keynesianism.[14] Capitalism was acceptable to social democrats only if capitalism's typical crises could be prevented and if mass unemployment could be averted, therefore Keynesianism was believed to be able to provide this.[14] Social democrats came to accept the market for reasons of efficiency and endorsed Keynesianism as that was expected to reconcile democracy and capitalism.[14] According to Michael Harrington, this represented a compromise between capitalism and socialism. While the post-war period of social democracy saw several social democratic parties renouncing orthodox Marxism, they did not lose their revisionist Marxist character, nor did they stop looking at Marx for inspiration such as in the form of Marxist humanism.[172] However, Marxism was associated with the Marxism–Leninism as practiced in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc which social democracy rejected and regarded as "falsely claim[ing] a share in the Socialist tradition. In fact it has distorted that tradition beyond recognition". Rather than a close or dogmatic Marxism, social democracy favours an open and "critical spirit of Marxism".[173]

For Harrington, social democracy believes that capitalism be reformed from within and that gradually a socialist economy will be created. The "social democratic compromise" involving Keynesianism led to a capitalism under socialist governments that would generate such growth that the surplus would make possible "an endless improvement of the quality of social life". According to Harrington, the socialists had become the "normal party of government" in Europe while their "conservative opponents were forced to accept measures they had once denounced on principle". Although this socialist pragmatism led in theory and practice to utopias hostile to one another, they all shared basic assumptions. This "social democratic compromise" goes back to the 1930s, when there was "a ferment in the movement, a break with the old either/or Kautskyan tradition, a new willingness to develop socialist programs that could work with and modify capitalism, but that fell far short of a "revolutionary" transformation".[174]

After the 1945 general election, a Labour government was formed by Clement Attlee. Attlee immediately began a program of major nationalization of the economy.[175] From 1945 to 1951, the Labour government nationalized the Bank of England, civil aviation, cable and wireless, coal, transport, electricity, gas and iron and steel.[175] This policy of major nationalizations gained support from the left faction within the Labour Party that saw the nationalizations as achieving the transformation of Britain from a capitalist to socialist economy.[175]

The Labour government's nationalizations were staunchly condemned by the opposition Conservative Party.[175] The Conservatives defended private enterprise and accused the Labour government of intending to create a Soviet-style centrally planned socialist state.[175] Despite these accusations, the Labour government's three Chancellors of the Exchequer, namely Hugh Dalton, Stafford Cripps and Hugh Gaitskell, all opposed Soviet-style central planning.[175] Initially, there were strong direct controls by the state in the economy that had already been implemented by the British government during World War II, but after the war these controls gradually loosened under the Labour government and were eventually phased out and replaced by Keynesian demand management.[175] In spite of opposition by the Conservatives to the nationalizations, all of the nationalizations except for that of coal and iron soon became accepted in a national post-war consensus on the economy that lasted until the Thatcher era in the late 1970s, when the national consensus turned towards support of privatization.[175]

The Labour Party lost the 1951 general election and a Conservative government was formed. There were early major critics of the nationalization policy within the Labour Party in the 1950s. In The Future of Socialism (1956),[176] British social democratic theorist Anthony Crosland argued that socialism should be about the reforming of capitalism from within.[177] Crosland claimed that the traditional socialist programme of abolishing capitalism on the basis of capitalism inherently causing immiseration had been rendered obsolete by the fact that the post-war Keynesian capitalism had led to the expansion of affluence for all, including full employment and a welfare state.[178] He claimed that the rise of such an affluent society had resulted in class identity fading and as a consequence socialism in its traditional conception as then supported by the British Labour Party was no longer attracting support.[178] Crosland claimed that the Labour Party was associated in the public's mind as having "a sectional, traditional, class appeal" that was reinforced by bickering over nationalization.[178] He argued that in order for the Labour Party to become electable again it had to drop its commitment to nationalization and to stop equating nationalization with socialism.[178] Instead of this, Crosland claimed that a socialist programme should be about support of social welfare, redistribution of wealth and "the proper dividing line between the public and private spheres of responsibility".[178] In post-war Germany, the SPD endorsed a similar policy on nationalizations to that of the British Labour government. SPD leader Kurt Schumacher declared that the SPD was in favour of nationalizations of key industrial sectors of the economy such as banking and credit, insurance, mining, coal, iron, steel, metal-working and all other sectors that were identified as monopolistic or cartelized.[179]

Upon becoming a sovereign state in 1947, India elected the social democratic Indian National Congress into government, with its leader Jawaharlal Nehru becoming the Indian prime minister. Upon his election as prime minister, Nehru declared: "In Europe, we see many countries have advanced very far on the road to socialism. I am not referring to the communist countries but to those which may be called parliamentary, social democratic countries".[180] While in power, Nehru's government emphasized state-guided national development of India and took inspiration from social democracy, although India's newly formed Planning Commission also took inspiration from post-1949 China's agricultural policies.[181] The social democratic Sri Lanka Freedom Party dominated post-independence politics in Sri Lanka too, practising secular government and affiliation to the Non-Aligned movement. A social democratic movement also emerged in Pakistan, in particular All Pakistan Awami Muslim League, founded in 1949 in Dhaka, then East Pakistan, which, under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, led the movement for Bangladesh's independence in 1971 and won its first democratic elections in 1973, before being overthrown in a military coup in 1975.

In 1949, the newly independent and sovereign state of Israel elected the social democratic Mapai. The party sought the creation of a grassroots mixed economy based on cooperative ownership of the means of production via the kibbutz system while rejecting nationalization of the means of production.[182] The kibbutz are producer cooperatives which have flourished in Israel through government assistance.[183]

In 1959, the SPD instituted a major policy review with the Godesberg Program.[184] The Godesberg Program eliminated the party's remaining orthodox Marxist policies and the SPD redefined its ideology as freiheitlicher Sozialismus (liberal socialism).[184] With the adoption of the Godesberg Program, the SPD renounced orthodox Marxist determinism and classism. The SPD replaced it with an ethical socialism based on humanism and emphasized that the party was democratic, pragmatic and reformist.[185] The most controversial decision of the Godesberg Program was its declaration stating that private ownership of the means of production "can claim protection by society as long as it does not hinder the establishment of social justice".[186]

By accepting free-market principles, the SPD argued that a truly free market would in fact have to be a regulated market to not to degenerate into oligarchy. This policy also meant the endorsement of Keynesian economic management, social welfare and a degree of economic planning. Some argue that this was an abandonment of the classical conception of socialism as involving the replacement of the capitalist economic system.[186] It declared that the SPD "no longer considered nationalization the major principle of a socialist economy but only one of several (and then only the last) means of controlling economic concentration of power of key industries" while also committing the SPD to an economic stance which promotes "as much competition as possible, as much planning as necessary".[187] The decision to abandon the traditional anti-capitalist policy angered many in the SPD who had supported it.[185]