Between the 12th century and modern times, the Swiss city of Basel has been home to three Jewish communities. The medieval community thrived at first but ended violently with the Basel massacre of 1349. As with many of the violent anti-Judaic events of the time, it was linked to the outbreak of the Black Death. At the end of the 14th century, a second community formed. But it was short-lived and disbanded before the turn of the century. For the following 400 years, there was no Jewish community in Basel. Today, there are several communities, ranging from liberal to religious to orthodox, and there are still more Jews who don’t belong to any community.

The First Jewish Community

A Jewish community had formed in Basel in the late 12th to early 13th century, migrating from the Rhineland. A synagogue and a Jewish cemetery existed in the 13th century. The cemetery was located next to the Petersplatz, on the site of the university building (Kollegienhaus). During its construction in 1937, more than 150 graves were discovered, as well as many fragmented gravestones.

The Jews of Basel were tradesmen, doctors, scribes, and moneylenders, a trade that was forbidden by the church but permitted by rabbis. Their main customers were the urban upper class of bishops and nobility. Excluded from the guilds, the Jewish community relied on trade for their products.

A noteworthy transaction is recorded in a loan document from 1223. Bishop Heinrich of Basel temporarily transferred the cathedral treasury to the Jews of Basel in order to obtain a loan. He used the money to fund the construction of the Mittlere Rheinbrücke, one of the first bridges across the Rhine in the area, and played a decisive role in the development of trade in Basel. There was a toll of 30 silver marks for mules, horses and goods crossing the bridge, which the bishop transferred to his own pocket until he could settle the debt. The procedure of placing Christian treasures and religious artefacts as collateral for a loan from Jewish moneylenders was common, but dangerous for Jews, inciting widespread anti-Jewish sentiment.[1][2]

Little is known about anti-Jewish riots in 13th century Europe, but it is clear that the Jews were endangered. Their legal situation was precarious, since they were not under the direct protection of the city authorities (bishop and nobility), but under the indirect protection of the empire. Anti-Jewish propaganda in Basel is well documented.

The Basel Massacre

With the spread of the Black Death in the 14th century, there were pogroms against Jews triggered by rumours of well poisoning. Already at Christmas 1348, before the plague had reached Basel, the Jewish cemetery was destroyed and a number of Jews fled the city. In January 1349, there was a meeting between the bishop of Strasbourg and representatives of the cities of Strasbourg, Freiburg and Basel to coordinate their policy in face of the rising tide of attacks against the Jews in the region, who were nominally under imperial protection.

The pogrom was committed by an angered mob and was not legally sanctioned by the city council or the bishop. The mob captured all remaining Jews in the city and locked them into a wooden hut they constructed on an island in the Rhine (the location of this island is unknown, it was possibly near the mouth of the Birsig, now paved-over). The hut was set alight and the Jews locked inside were burned to death or suffocated.

The number of 300 to 600 victims mentioned in medieval sources is not credible; the entire community of Jews in the city at the time was likely of the order of 100, and many of them would have escaped in the face of persecution in the preceding weeks. A number of 50 to 70 victims is thought to be plausible by modern historians. Jewish children appear to have been spared, but they were forcibly baptized and placed in monasteries. It appears that also a number of adult Jews were spared because they accepted conversion.[3]

Similar pogroms took place in Freiburg on 30 January, and in Strasbourg on 14 February. The massacre had notably taken place before the Black Death had even reached the city. When it finally broke out in April to May 1349, the converted Jews were still blamed for well poisoning. They were accused and partly executed, partly expulsed. By the end of 1349, the Jews of Basel had been murdered, their cemetery destroyed and all debts to Jews declared settled.[4]

The Second Jewish Community

Following the expulsion of the Jews in 1349, Basel publicly resolved to not allow any Jews back into the city for at least 200 years. However, less than 15 years later, in the wake of the disastrous earthquake of 1356, Jews were allowed back and by 1365, the existence of a second Jewish community is documented. It is estimated to have numbered about 150 people (out of a total population of some 8,000) by 1370.[5] A building on the corner of Grünpfahlgässlein and Gerbergasse served the second community as a synagogue. From 1394, they briefly used a site on Hirschgässlein as a cemetery. It was still listed as “Garden of Eden” as late as the 16th century in Sebastian Münster's city map, although there was no longer a Jewish community in Basel at that time. It is possible that it was still used by Jews living elsewhere in the region.[6]

The Jewish community left the city again in 1397, this time voluntarily, in spite of attempts by the city council to retain them, moving east into Habsburg territories, perhaps fearing renewed persecution in the face of a climate of anti-Judaic sentiment in the Alsace in the 1390s. This time, the dissolution of the Jewish community was long-lasting, with the modern Jewish community in Basel established only after more than four centuries, in 1805.[7]

400 Years without a Jewish Community

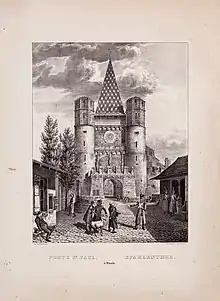

In 1398, the city gate “Spalentor” was built during an extension of the walls, which had been partly destroyed by the earthquake. The gravestones from the cemetery of the first Jewish community were used alongside other stones and debris for the construction of the wall. Several early historical scholars mention these gravestones, among them Johannes Tonjola. In his introduction to Basilea Sepulta, 1661, he describes counting 570 Hebrew gravestones when walking along the city wall.

In 1859, the city walls were demolished in order to increase space and improve hygiene conditions in the city. The debris from the demolished walls were used to fill in the city moat, and these areas were converted into streets and green spaces, which largely still bear names referring to the original wall. During this process, most of the embedded gravestones were lost. Only a few of them remain. Ten are on display in the courtyard of the Jewish Museum of Switzerland.

From about 1500, Basel became a centre of scholarly study of Judaism. Hebrew was taught at the University of Basel, and the Basel printing presses gained worldwide fame with their prints of Jewish writings. In 1578 Ambrosius Froben published a censored edition of the Babylonian Talmud. In 1629, the Basel theologian Johann Buxtorf the Younger translated the religious philosophical work Führer der Unschlüssigen by the medieval Jewish scholar Maimonides, and in 1639 he completed the Lexicon chaldaicum, talmudicum et rabbinicum, begun by his father Johann Buxtorf the Elder. These works were largely censored by the authorities. Jewish editors were allowed to stay in Basel for the purpose of proofreading and typesetting. However, their residence permits were temporary, and the city resolutely excluded Jews between the 16th and 18th centuries, also in the villages surrounding Basel.[8]

Jewish tradesmen were permitted during the daytime, as customs duties of the time indicate. In 1552 the Basel Council decided on a “Jew toll of 6 shillings”, taxing humans like goods and animals. A customs order for the Spalentor in 1775 shows a list of charges that includes Jews.

Another anti-Judaic measure was the dice toll. Travelling Jews in Switzerland, Germany and Liechtenstein often had to pay with dice in addition to the required customs money. Symbolically, this referred to the soldiers who played dice for Jesus' clothes at the foot of the cross. The practice of dice toll was not only humiliating for travelling Jews, but also very inconvenient, as the dice were not only demanded at customs posts, but also by hostile bystanders.[9] In Switzerland, the dice toll was largely replaced by financial regulations during the course of the 17th century. After the French Revolution, France (among others) put pressure on Basel to end discriminatory measures, and in 1794, the Jew toll was likewise abolished.[10]

The Third Jewish Community

With the French Revolution granting Jews equal rights in 1791, and the Helvetic Republic proclaimed in 1798, Jews were granted legal equality – on paper. In practice, Jews initially received the rights of settled Frenchmen instead of Swiss citizenship. After the dissolution of the Helvetic Republic, the new measures were reversed, and it was only in 1872 that Jews were granted full citizenship in Basel. Although the Swiss referendum of 1866 committed to giving Jews full and equal residency and trading rights, these were not fully implemented in Switzerland until 1874. However, the religious freedom granted during the Helvetic Republic paved the way for the third Jewish community of Basel, which was established around 1805. Sources cite between 10 and 35 Jewish families living in Basel around that time.

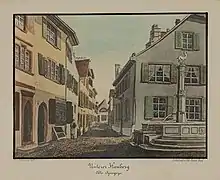

Unterer Heuberg was the site of a small synagogue built in the 1840s. It was the first prayer house belonging exclusively to the Jewish community, while previously Jews prayed in their private homes. The old synagogue was used until 1868, when the Great Synagogue (Grosse Synagoge Basel) was inaugurated. Following the 1871 annexation of Alsace by the Germans, many Alsatian Jews moved to Basel. Other newcomers came from the Southern Germany and from the Swiss “Judendörfer” Endingen and Lengnau, where Jews were allowed to settle since the 17th century. To accommodate the growing community, the Great Synagogue was expanded in 1892, just 30 years after its construction.[11]

Among the many Jews migrating to Basel from Alsace was the family of the young Alfred Dreyfus, who gained fame in the so-called “Dreyfus affair.” The hatred and anti-Semitism displayed in the scandal surrounding his public shaming amplified calls for a Jewish state. The writer and journalist, Theodor Herzl, organised the first Zionist congress, which took place in Basel in 1897. Later, 10 of the 22 Zionist congresses took place there. Although the congresses met largely with public sympathy, many Jews in Basel maintained a guarded attitude to Zionism until the rise of National Socialism in Germany.

For about a century, the Jewish community of Basel buried their dead in Hegenheim (Jüdischer Friedhof Hegenheim). Efforts to establish a Jewish cemetery in Basel were finally successful in 1903, when the cemetery in Theodor Herzl street opened.

In 1900, the Jewish population of Basel counted around 1900 people. Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany starting in 1933 brought this number up to 3000. After 1938, Jewish passports were marked with a red J, identifying them so that they could be more easily turned back at the border. According to Swiss regulations, the religious communities were responsible for supporting their co-religionists financially.

In 1966, the Jewish Museum of Switzerland opened in the Kornhausgasse. It was the first Jewish museum in German-speaking Europe, predating the oldest German Jewish museums in Augsburg and Frankfurt by 22 years. The museum contains many objects relevant to the Jewish history of the area.

In 1973, the Israelitische Gemeinde Basel (or IGB) became the first Jewish community in Switzerland to be recognised under public law, giving it the same status as the national churches.

In 1998, the university established the Zentrum für Jüdische Studien, a center for Jewish studies.

Basel is home to both liberal and conservative Jewish families. There is also an orthodox community, the “Israelitische Religionsgesellschaft Basel,“ which split from the IGB in 1927. In 2004, liberal Jews founded Migwan. Since the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, many Basel Jews have moved away. The ageing population and a general trend of secularism have contributed to the decline in the Jewish population of Basel. While there were still about 2000 Jews in Basel in 1980, the number sank to 1218 in 2004 and to just over 1100 in 2009.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ "Zur Verpfändung sakraler Kultgegenstände an Juden im mittelalterlichen Reich: Norm und Praxis" (PDF).

- ↑ "Der "Europäische Tag der Jüdischen Kultur" schlägt Brücken".

- ↑ "The Jewish Community of Basel". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ Haumann, Erlanger, Kury, Meyer, Wichers, Heiko, Simon, Patrick, Werner, Hermann (1999). Juden in Basel und Umgebung Zur Geschichte einer Minderheit. Darstellung und Quellen für den Gebrauch an Schulen. Schwabe Verlagsgruppe AG Schwabe Verlag.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Nolte (2019), p. 71

- ↑ Haumann, Erlanger, Kury, Meyer, Wichers (1999). Juden in Basel und Umgebung Zur Geschichte einer Minderheit. Darstellung und Quellen für den Gebrauch an Schulen. Schwabe Verlagsgruppe AG Schwabe Verlag.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Katia Guth-Dreyfus, 175 Jahre Israelitische Gemeinde Basel (1980).

- ↑ Juden in Basel und Umgebung Zur Geschichte einer Minderheit. Darstellung und Quellen für den Gebrauch an Schulen.

- ↑ Lubrich, Battegay, Naomi, Caspar (2018). Jüdische Schweiz. 50 Objekte erzählen Geschichte / Jewish Switzerland. 50 objects tell their stories. Basel: Christoph Merian Verlag. ISBN 978-3-85616-847-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Wolf, Arthur (1909). Die Juden in Basel. 1543 - 1872. Basel.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Juden in Basel und Umgebung Zur Geschichte einer Minderheit. Darstellung und Quellen für den Gebrauch an Schulen.

- ↑ "Factsheet Basel" (PDF).

- Heiko Haumann (ed.), Acht Jahrhunderte Juden in Basel, Schwabe AG (2005).

- Achim Nolte, Jüdische Gemeinden in Baden und Basel (2019).

- Caspar Battegay, Naomi Lubrich: Jüdische Schweiz. 50 Objekte erzählen Geschichte / Jewish Switzerland. 50 objects tell their stories. Christoph Merian Verlag, Basel 2018, ISBN 978-3-85616-847-6