| Huanjing bunao | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 還精補腦 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 还精补脑 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 환정 보뇌 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 還精補腦 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 還精補脳 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | かんせい ほどう | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Huanjing bunao (traditional Chinese: 還精補腦; simplified Chinese: 还精补脑; lit. 'returning the semen/essence to replenish the brain' or coitus reservatus) is a Daoist sexual practice and yangsheng ("nourishing life") method aimed at maintaining arousal for an extended plateau phase while avoiding orgasm. According to this practice, retaining unejaculated jing (精, "semen; [medical] essence of life") supposedly allows it to rise through the spine to nourish the brain and enhance overall well-being. Daoist adepts have been exploring various methods to avoid ejaculation for more than two thousand years. These range from meditative approaches involving breath-control or visualization to manual techniques such as pressing the perineum or squeezing the urethra.

In traditional Chinese medical theory, the shen (腎, "kidney") organ system was considered the reservoir for semen, bone marrow, brain matter, and other bodily fluids. However, in actual fact, huanjing bunao often leads to retrograde ejaculation, which redirects the semen into the bladder, from where it is expelled along with urine. Anatomically speaking, circulating seminal fluid or "seminal essence" throughout the body is impossible. While this ancient Chinese practice has historical and sexological significance, its physiological effects do not align with the traditional beliefs surrounding it.

Terminology

The present Chinese term huánjīng bǔnǎo comprises two disyllabic words.

Huánjīng (還精) compounds two semantically complex words. Huán (還) has English translation equivalents of: (1) "turn round, come round; go back, come back, return to previous location or to original condition; (re)cycle, revert", (2) "send back, send in return; answer. give back, remit; redeem; recompense; restore. rebound against one, come round again (whence it began)." (Kroll 2015: 170; note, all definitions condensed to relevant meanings). Jīng (精) translates as: (1) "essence; purest, most highly concentrated element (< finest bleached rice). pith, marrow, gist", (2) "germinal essence, life-germ contained in the Dao. the energy that nourishes the human body and is esp. attached to sexuality (semen, menstrual fluid); seminal; vital; seed(ling)", (3) "quintessence; purest, finest, most characteristic, very best of. concentrate(d), condensed, consolidated. subtle; delicate, fine." (Kroll 2015: 216). Although jing means "semen" in the expression huanjing bunao, "it would be a great mistake to read jing as always referring only to the material secretion itself" (Needham and Lu 1983: 66). The "making the semen return upwards to nourish the brain" technique was another instance of the Daoist emphasis on "reversion, restoration, regeneration, counter-current motion. and cyclical transformation" (Needham and Lu 1983: 31).

Bǔnǎo (補腦) compounds two comparatively simpler words. Bǔ (補) has equivalents of: (1) #"mend or patch clothing", (2) "repair, restore; remedy, redress; improve, ameliorate", (3) "add to, supplement; supplete, supply (a deficiency); replenish." (Kroll 2015: 29). Nǎo (腦) translates into English as: "the brain. [medieval Chinese] one's head, noggin: also, top part." (Kroll 2015: 320).

There is no standard English translation of Chinese huanjing bunao, and here are twenty samples:

- "making the ching return to restore the brain" (Needham and Wang 1956: 150)

- "making the semen return to strengthen the brain" (van Gulik 1961: 78)

- "reverting the sperm to repair the brain" (Ware 1966: 140)

- "making the essence return (so as) to repair the brain" (Maspero 1981: 495)

- "making the semen return upwards to nourish the brain" (Needham and Lu 1983: 30)

- "returning the seminal essence and replenishing the brain" (Harper 1987: 549)

- "making the seminal essence return to nourish the brain" (Ruan 1991: 96)

- "returning the ching to nourish the brain" (Wile 1992: 50)

- "to return of the essence to repair the brain" (Schipper 1993: 242)

- "return [semen's] essence to the brain to fortify it" (Bokenkamp 1997: 87)

- "returning the essence to replenish the brain" (Harper 1998: 151)

- "conducting the seminal essence to repair the brain" (Baldrian-Hussein 2004: 808)

- "return of the sperm in order to repair the brain" (Schipper 2004: 786)

- "returning the essence to replenish the brain" (Despeux 2008: 515)

- "returning the semen to supplement the brain" (Judy 2015: 135)

- "returning the sperm to nourish the brain" (Umekawa and Dear 2018: 216)

- "reverting the essence to replenish the brain" (Pregadio 2022: 438)

- "to revert the essence and to replenish the brain (marrow)" (Pfister 2022: 344)

- "return the essence to nourish the brain" (Wang 2022: 359)

- "returning the semen to the brain" (Rocha 2022: 384)

Huan (還) is usually translated as "return", except for three "revert" and one "conduct". Jing (精) is rendered as seven "essence", four "semen", three "seminal essence" and one "[semen's] essence", three "sperm", and two "ching"—in Chinese usage, both jingzi (精子) and jingye (精液) mean "semen; sperm". Bu (補) is given as five each for "repair", "replenish", and "nourish"; and one each for "strengthen", "fortify", "supplement", "restore", and untranslated (Rocha 2022). Nao (腦) consistently has nineteen "brain" translations and one "brain (marrow)". Overall, there is notable diversity among these translations of the phrase, only two (Harper 1998 and Despeux 2008) are identical "returning the essence to replenish the brain"; and some translators revised their earlier versions, such as (Harper 1987, 1998) and (Needham 1956, 1983).

Scholars have discussed the Chinese huanjing bunao sexual practice and related Western techniques in Latin biological terms based on coitus (meaning "sexual intercourse").

- Coitus interruptus (from interruptus "interrupted, cut short"), commonly known as the "withdrawal method" or "pulling out," is an ancient contraceptive method consisting in removing the penis from the vagina before ejaculation.

- Coitus saxonicus (saxonicus "Saxon, West Germanic tribes") or coitus thesauratus (thesauratus "repository, treasure") is a widespread birth-control method consisting of squeezing the urethra at the base of the penis before ejaculation, resulting in retrograde ejaculation.

- Coitus reservatus (with reservatus "reserved, saved") or coitus conservatus (conservatus "preserved, conserved") is a semen-retention practice in which a man intentionally avoids or delays ejaculating during intercourse, typically by pressing on the perineum, and sometimes resulting in retrograde ejaculation.

The sinologist Joseph Needham refined his translations of huanjing bunao. Initially, he held that the technique was not coitus interruptus as van Gulik "inadvertently" said, but "coitus reservatus, numerous intromissions with a succession of partners occurring for every one ejaculation." (Needham and Ling 1956: 149). Subsequently, Needham reconsidered the problems of nomenclature. Huanjing bunao should neither be translated coitus interruptus because that term is reserved for "the contraceptive method of sudden withdrawal and external ejaculation," nor coitus reservatus because that usually means "allowing the state of excitation to fade without a withdrawal". He suggested two neologisms for accurately translating the Chinese methods; coitus conservatus for "seminal retention and withdrawal after female orgasm" and coitus thesauratus for the coitus saxonicus retrograde ejaculation "'re-routing' of the secretion into the bladder". (Needham and Lu 1983: 199). Authors inconsistently use these terms for both coitus siccus "copulation without ejaculation" and coitus pluvius "copulation followed by ejaculation".

Note that in quotations below, the romanization of Chinese is standardized into Pinyin, for instance, Wade-Giles ch'i, Simplified Wade chhi (used by Needham), and other transcription systems are converted to qi (氣, "breath; vital force").

Han dynasty

.jpg.webp)

The archeological discovery and analysis of medical manuscripts in the 1970s revealed that the origins of Chinese sexual cultivation techniques dated back to at least the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BCE), rather than the early Han dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE), as previously believed (Needham and Lu 1983: 199).

Mawangdui excavated texts

Seven previously unknown medical and sexological manuscripts, along with the famous Mawangdui Silk Texts, were excavated in 1973 from a Western Han tomb dated 168 BCE (see Harper 1998 for details). Five were written on silk, such as the Wushi'er Bingfang (Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments), and the other two manuscripts written on bamboo and wooden slips each transcribed two different texts bound separately and rolled together in a single bundle. Although none of them directly refer to the huanjing bunao 還精補腦, "returning the semen/essence to replenish the brain") techniques, three sexual cultivation bamboo-slip manuscripts mention aspects later associated with essence retention, accumulating and enclosing jing within the body, stimulating the penis, contracting the anus, and controlled stages of intercourse with ejaculation, all of which were believed to increase longevity and spiritual enlightenment. In the Mawangdui medical manuscripts, Chinese jing "essence" consistently names an internal material similar in nature to qi "vapor", and is not equivalent to "semen". In fact, no word for "semen" occurs although it is implicit in several passages (Harper 1998: 152).

First, the Shiwen (十問, Ten Questions) manuscript consists of ten dialogues between legendary sages including the Yellow Emperor, Yao, and Shun. One passage exemplifies Chinese euphemisms referring to sexual terminology.

When coitus with Yin [jieyin, 接陰 "sexual intercourse"] is expected to be frequent, follow it with flying creatures. The spring dickeybird’s [que (雀, "sparrows; other small wild birds")] round egg arouses that crowing cock [mingxiong (鳴雄, "crowing cock") can refer to both the male bird and the man's penis]. The crowing cock has an essence. If you are truly able to ingest this, the jade whip [penis] is reborn. Best is engaging the member. Block that jade hole [vagina]. When brimming then have intercourse, and bid farewell with round eggs. If the member is not engaged, conserve it with roasted-wheat meal. If truly able to ingest this, you can raise the dead [revitalize the penis]. (Harper 1998: 443, 456-458)

Both the Shiwen and the Tianxia zhidao tan below describe accumulating and enclosing qing ("semen; life essence") in an enigmatic corporal space called the yubi (玉閉, "jade closure"), where shenming (神明, "spiritual illumination") occurs. Harper notes bi (閉) is a standard term for "concentrating vapor and essence inside the body by 'enclosing' them" (1998: 457). Biqi (閉氣, "hold the breath closed in; apnea") is a related word used in embryonic breathing (Maspero 1981: 342).

[manuscript lacuna …] and take the essence. Attend to that conjoining of vapor [heqi 合氣, "sexual intercourse"], and lightly move her form. When able to move her form and bring forth the five tones [a woman's vocalizations during sex], then absorb her essence. Those who are empty can be made brimming full; the vigorous can be made to flourish lastingly; the aged can be made to live long. The procedure for living long is to carefully employ the jade closure. When at the right times the jade closure enfolds, spirit illumination arrives and accumulates. Accumulating, it invariably manifests radiance. When the jade closure firms the essence, this invariably ensures that the jade wellspring [yuquan 玉泉] is not upset. Then the hundred ailments do not occur; thus you can live long. (Harper 1998: 444, 458)

The subsequent Shiwen passage lists nine stages of zhi (至, "arrival; 'coming'", i.e., "thrusting the penis inside the vagina") without ejaculation.

In the way of coitus with Yin [intercourse], stay the heart, settle and secure it; and the form and vapor secure one another. Thus it is said: at the first arrival without emission, ears and eyes are perceptive and bright; at the second arrival without emission, the voice’s vapor rises high; at the third arrival without emission, skin and hide glow; at the fourth arrival without emission, spine and upper side suffer no injury; at the fifth arrival without emission, buttock and ham can be squared; at the sixth arrival without emission, the hundred vessels pass clear through; at the seventh arrival without emission, your entire life is without calamity; at the eighth arrival without emission, you can have a lengthy longevity; at the ninth arrival without emission, you penetrate spirit illumination. (Harper 1998: 444, 458)

Some Mawangdui manuscript paleographers suggest that the Shiwen contains the earliest documentation of huanjing bunao ("returning the essence to replenish the brain"), depending upon whether the unusual character liu (月留) should be read as a copyist's error for nao (腦, "brain") or a graphic loan character for bao (胞, "womb; placenta"). The context describes an ancient method for "coitus with Yin to become strong" and "sucking in heaven's essence to achieve longevity." King Pan Geng is told,

Your lordship must prize that which is born together with the body and yet grows old ahead of the body [the penis]. The weak, it makes them strong; the short, it makes them tall; the poor, it guarantees them abundant provisions. The regimen involves both emptying and filling, and there is a precise procedure for cultivating it. First, relax the limbs, straighten the spine, and flex the buttocks; second, spread the thighs, move the Yin [penis], and contract the anus; third, draw the eyelashes together, do not listen, and suck in the vapor to fill the womb [月留]; fourth, contain the five tastes and drink that wellspring blossom an internally produced fluid; fifth, the mass of essence all ascends, suck in the great illumination. After reaching the fifth, stop. Essence and spirit grow daily more blissful.” (Harper 1998: 449, 465-467)

Wile translates liu as "brain", "stimulate the penis ... contract the anus ... absorb the [qi] to fill the brain ... all the [jing] will rise upward" (1992: 58). However, based upon similar textual usages, Harper translates it as "womb", hypothetically meaning "a 'womb-like organ' where men as well as women store vapor and essence", and disputes the "brain" interpretation because "filling the womb" occurs in the third of five stages, whereas "replenishing the brain" is regularly the final stage in sexual cultivation (1998: 465–467).

Second, the He yinyang (合陰陽, Conjoining/Uniting Yin and Yang; a standard term for sexual intercourse) manuscript begins with a jargonized method for doing it,

Grip the hands [make a fist with the thumb tucked in], and emerge at the Yang side [outside] of the wrists; Stroke the elbow chambers; Press [or go to] the side of the underarms; Ascend the stove trivet [between the breasts]; Press the neck zone; Stroke the receiving canister [pelvic region]; Cover the encircling ring [waist]; Descend the broken basin [clavicle]; Cross the sweet-liquor ford [breasts]; Skim the Spurting Sea [navel]; Ascend Constancy Mountain [female genitals]; Enter the dark gate [vagina]; Ride the coital muscle [responsible for the female orgasm]; Suck the essence and spirit upward. Then you can have lasting vision and exist in unison with heaven and earth. (Harper 1998: 473, 477, 479).

Compare the Shiwen parallel above saying the "mass of essence all ascends". In contrast with this "essence and spirit" translation for jingshen (精神), Wile translates "By sucking her jing spirit upward" and notes "jing spirit" should be understood as "essentially sexual energy." (1992: 78, 223). This context continues with the "signs of the five desires" (e.g., the second is "the nipples harden and her nose sweats—slowly embrace") and says,

When the signs are complete, ascend. Jab upward but do not penetrate inside, thereby bringing the vapor [qi]. When the vapor arrives penetrate deeply inside and thrust it upward, thereby dispensing the heat. Then once again bring it back down. Do not let the vapor spill out, lest the woman become greatly parched. (Harper 1998: 474)

In the last sentence, Harper reads the manuscriptal jie (楬, "peg; tally") as a graphic loan character for jie (偈, "forceful; parch") meaning that when intercourse is excessive, "the penis must still block the vaginal opening in order to seal the sexually generated essence inside" (1998: 481, 501).

A subsequent He yinyang passage differentiates jing essences by gender.

In the evening the man’s essence flourishes; in the morning the woman’s essence accumulates. By nurturing the woman’s essence with my essence, muscles and vessels both move; skin, vapor, and blood are all activated. Thus, you are able to open blockage and penetrate obstruction. The central cavity receives the transmission and is filled. (Harper 1998: 476, 484).

Third, the Tianxia zhidao tan (天下至道谈, Discussion of the Culminant Way in Under-Heaven) bamboo document says that enclosing jing ("essence") can result in achieving shenming (神明, "spirit illumination").

O be careful indeed! The matter of spirit illumination lies in what is enclosed [bi 閉]. Vigilantly control the jade closure [yubi 玉閉], and spirit illumination will arrive. As a rule, to cultivate the body the task lies in accumulating essence. When essence reaches fullness, it invariably is lost; when essence is deficient, it must be replenished. As for the time to replenish a loss, do it when essence is deficient. To do it, conjoin in a sitting position; tailbone, buttocks, nose, and mouth each participate at the proper time [i.e., engage in sexual intercourse]. (Harper 1998: 491, 498)

Compare Wile's above translation of yubi (玉閉, "jade closure"), "The matter of achieving spiritual illumination consists of locking. If one carefully holds the "jade" in check, spiritual illumination will he achieved." (1992: 80).

Another context, described as the "free-handed method" (Pfister 2022: 343), refers to anal constriction during sexual coitus, but does not specify pressing on the zuan (簒, "usurp; perineum")

While having intercourse, to relax the spine, suck in the anus, and press it down is “gathering vapor.” While having intercourse, to not hurry and not be hasty, and to exit and enter with harmonious control is “harmonizing the fluid.” When getting out of bed, to have the other person make it [the penis] erect and let it subside when angered is “accumulating vapor.” When nearly finished, to not let the inner spine move, to suck in the vapor press it down, and to still the body while waiting for it is “awaiting fullness.” To wash it after finishing and let go of it after becoming angered is “securing against upset.” (Harper 1998: 493, 500)

Washing the penis is intended to bring about detumescence (Harper 1998: 501).

Received texts

Prior to the Mawangdui discoveries, scholars relied on received texts of Chinese classics to understand the origins of huanjing bunao. For instance, the Yiwenzhi bibliographical section of the 111 CE Book of Han lists the Rong Cheng yin dao (容成陰道, Rong Cheng's Way of Lovemaking) in 26 chapters, along with several other lost texts on sexual cultivation.

The earliest known attestation of huanjing bunao is the c. 2nd century CE Xiang'er commentary (to Daodejing 9) that condemns the practice (Harper 1998: 467). At this early stage of huanjng bunao practice, note the use of si (思, "think, think of") denoting "contemplate, meditate" on essence rather than semen.

The Dao teaches people to congeal their essences and form spirits [結精成神]. Today, there are in the world false practitioners who craftily proclaim the Dao, teaching by means of texts attributed to the Yellow Thearch, the Dark Maiden, Gongzi, and Rongcheng. They say that during intercourse with a woman one should not release the semen, but through meditation return its essence to the brain to fortify it [思還精補腦]. Since their [internal] spirits and their hearts are not unified, they lose that which they seek to preserve. Though they control their delight, they may not treasure it for long. (Bokenkamp 1997: 43)

Based upon a misquotation in the transmitted 5th century Book of the Later Han, several authorities have contended that huanjing bunao was first recorded in the 2nd century CE Liexian zhuan ("Biographies of Exemplary Transcendents") hagiography of Rong Chenggong (容成公), one of the semi-legendary founding fathers of Chinese sexology: "One should firmly hold [the penis] with the hand, not ejaculate, and let the essence revert to replenish the brain." (Despeux 2008: 515).

The Book of the Later Han biography of Ling Shouguang (冷壽光) says he was an expert on the sexual techniques of Rong Cheng, and the commentary quotes the Liexian zhuan.

The Venerable Rong Cheng was good at the affairs of 'restoring' [bu 補] and 'conducting' [dao 導]. He could gather the [jing] from the 'Mysterious Feminine'. The essential point of this art is to guard the life-force and to nourish the [qi] by (relying on) the 'Valley Spirit that never dies' [both the Mysterious Feminine and Valley Spirit refer to the Daodejing 6]. When this is done white hairs become black again, and teeth that have dropped out are replaced by new ones. The art of commerce [intercourse] with women is to close the hands tightly and to refrain from ejaculation, causing the sperm to return and nourish the brain. (Needham and Lu 1983: 198).

Although Needham and Lu claim the last sentence was "expurgated" from the original Liexian zhuan, the huanjing bunao reference belongs to the commentary and not the original text (Harper 1998: 467).

The Quanzhen School hagiographer Zhao Daoyi (趙道一, fl. 1294–1307), compiler of the Lishi zhenxian tidao tongjian (歷世真仙體道通鋻, Comprehensive Mirror of Immortals Who Embodied the Way Through the Ages), notes he chose to omit the tradition that "Some say that Sire Rong Cheng obtained the art of 'riding the woman,' by which one firmly grasps [the seminal vesicle] in order not to leak out the semen [but rather] cause it to return and so nourish the brain" because it probably resulted as "an erroneous divergence [from the earlier legend] by later generations." (Campany 2002: 534–535)

The reconstructed 2nd or 3rd century Sunü jing (素女經, The Classic of the Pure/Plain Woman) defines huanjing (還精, "returning the essence") as "to be aroused but not ejaculate", describes a man gathering and transforming the jing from a woman's mouth and returning it into his brain, and details the pleasures of refraining from ejaculation.

First, the Yellow Emperor asks Sunu about the results of refraining from intercourse for a long time, and she answers.

If the "jade stalk" [penis] does not stir, it dies in its lair. So you must engage frequently in intercourse as a way of exercising the body [daoyin 導引]. To be aroused but not ejaculate is what is called "returning the jing [還精]." When the jing is returned to benefit the body [還精補益], then the tao of life has been realized. (Wile 1992: 85)

Needham mistranslates daoyin (導引, "exercise; calisthenics; breath circulation") as "masturbation", despite correctly translating it more than ten times elsewhere in the book as "gymnastic techniques" and "massage" (Wile 1992: 59).

Therefore (if you insist on refraining from women) you should regularly exercise it (the Jade Stalk) by masturbation. If you can erect it (in orgasm) and yet have no ejaculation, that is called 'making the jing return', and making the jing return is of great restorative benefit, fully displaying the Tao of the life(-force). (Needham and Lu 1983: 201).

Second, the legendary ruler asks Sunu about how to regain strength when he cannot get an erection, and she recommends first harmonizing with his partner, then gathering her jing, transforming it into jingqi (精氣), and returning it to the brain.

The woman manifests "five colors" [displaying her mood] by which to assess her satisfaction. Gather her overflowing jing [采其精] and take the liquid from her mouth. The jingqi will be returned and transformed in your own body [精氣還化], filling the brain [填滿髓髒]. (Wile 1992: 86)

The translator notes that huan (還, "return") denotes the "process of raising the jing energy from its center at the base of the body up the back to the brain", and reads the character zang (髒, "dirty; defile") following as a variant of nao (腦, "brain"), that is, "return the jing to fortify the brain" (1992: 234).

Third, the goddess Cainü (采女, Selected Woman) asks Peng Zu, "The pleasure of intercourse lies in ejaculation. Now if a man locks himself and refrains from emission, where is the pleasure?", and he answers:

When jing is emitted the whole body feels weary. One suffers buzzing in the ears and drowsiness in the eyes; the throat is parched and the joints heavy. Although there is brief pleasure, in the end there is discomfort. If, however, one engages in sex without emission, then the strength of our qi will be more than sufficient and our bodies at ease. One's hearing will he acute and vision clear. Although exercising self-control and calming the passion, love actually increases, and one remains unsatiated. How can this be considered unpleasurable? (Wile 1992: 91)

Six dynasties

The historical term "Six Dynasties" (222-589) collectively refers to the Three Kingdoms (220–280 CE), Jin Dynasty (265–420), and Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589).

Ge Hong's c. 318 Baopuzi (Master Who Embraces Simplicity) provides early information about "returning the essence to replenish the brain" and related terms. Huanjing bujao occurs in two chapters. "The Ultimate System" lists it among common practices to nourish life.

Man's death ensues from losses, old age, illnesses, poisons, miasmas, and chills. Today, men do calisthenics and breathing exercises, revert their sperm to repair the brain, follow dietary rules, regulate their activity and rest, take medicines, give thought to their inner gods to maintain their own integrity, undergo prohibitions, wear amulets and seals from their belts, and keep at a distance all who might harm their lives. (5, Ware 1966: 103)

The "Resolving Hesitations" chapter praises the secret huanjing bunao practice, which had always been orally transmitted.

On the technology of sex at least ten authors have written, some explaining how it can replenish and restore injuries and losses, others telling how to cure many diseases by its aid, others again describing the gathering of the Yin force to benefit the Yang, others showing how it can increase one's years and protract one's longevity. But the great essential here is making the semen return to nourish the brain [還精補腦], a method which the adepts have handed down from mouth to mouth, never committing it to writing. If a man does not understand this art he may take the most famous (macrobiotic) medicines, but he will never attain longevity or immortality. Besides, the union of Yin and Yang in sexual life should not be wholly given up, for if a man does not have intercourse he will contract the diseases of obstruction and blockage by his slothful sitting, and end by those which arise from celibate depression and pent-up resentment—what good will that do for his longevity? On the other hand, over-indulgence diminishes the lifespan, and it is only by managing copulations so that the seminal dispersals are moderated, that damage can be avoided. Without the (right) oral instructions hardly a man in ten thousand will fail to injure and destroy himself in practising this art. The disciples of the Mysterious Girl and the Immaculate Girl, with the Venerable [Rong Cheng], and [Peng Zu], all had a rough acquaintance with it, but in the end they never committed to paper the most important part of it. Those bent upon immortality, however, assiduously seek this out. As for myself, I had instruction from my teacher [Zheng Yin 鄭隱], and I record it here for the benefit of future believers in the Tao, not retailing my own ideas. At the same time I must truthfully say that I feel I have not yet mastered everything that could be got from his instruction. (Lastly), some Taoists with a smattering of knowledge teach and follow the sexual techniques in order to pattern themselves on the holy immortals, without doing anything about the preparation of the great medicine of the Golden Elixir. Oh what a height of folly is this! (8, Needham and Lu 1983: 200-201)

The Baopuzi mentions huanjing taixi with Taixi (embryonic breathing) (還精胎息, "return the essence and breathe like an embryo") in the Rejoinder to Popular Conceptions chapter, which quotes a poem from a xianjing (仙經, Scripture on Transcendence):

Those who take [chemical] elixirs / And guard the primal unity / Will come to a stop from living / No sooner than Heaven itself; / Making the sperm return, / Breathing like babe in womb, / They will lengthen their days in peace / And blessing, world without end. (3, Needham and Lu 1983: 200)

Compare "Revert your sperm, breathe like fetus" (Ware 1966: 54).

The Baopuzi Genie's Pharmacopoeia chapter lists brain-supplementing sophora seeds among Daoist transcendence drugs. "Seal with clay in a new jar for twenty days or more, until the skin has fallen off Then wash the seeds, and they will be like soybeans. Taken daily, they will be especially good for repairing the brain. If one takes them for a long time, one's hair will not turn white, and one will enjoy Fullness of Life." (Ware 1966: 190–191).

Besides the usual word jing ("sperm"), the Baopuzi synonymously uses yindan (陰丹, "Yin elixir; sperm") in two contexts of bunao (補腦, "brain mending").

It is inadmissible that man should sit and bring illness and anxieties upon himself by not engaging in sexual intercourse. But then again, if he wishes to indulge his lusts and cannot moderate his dispersals, he hacks away at his very life. Those knowing how to operate the sexual recipes can check ejaculation, thereby repairing the brain [則能卻走馬以補腦]; revert their sperm to the Vermilion Intestine [還陰丹以朱腸]. (6, Ware 1966: 122)

If a man in the vigor of youth learns how to revert his years [還年], repairs his brain with his sperm [服陰丹以補腦], and gathers mucus from his nose, he will live not less than three hundred years without taking any medicines, but this will not bring him geniehood [transcendence]. (13, Ware 1966: 223).

The 2nd or 3rd century Huangting waijing yujing (黃庭外景玉經, Jade Manual of the External Radiance of the Yellow Courts; compare the Shangqing revelations Inner Scripture) is "filled with cryptic expressions and divine names" designed to exclude uninformed readers, and is addressed to learned Daoists already familiar with huanjing bunao techniques (Maspero 1981: 488, 523). For illustration,

The Mysterious Chest [inside of the throat] of the Breath Tube [tracheal artery] is the receptacle which receives the Essence; Take care to hold onto your Essence firmly and restrain yourself. […] Please yourself by exhaling and inhaling in the Hut [nose]; if you protect and keep (Essence and Breath) complete and firm, your body will receive prosperity; the interior of the Square Inch [Cinnabar Field], close it carefully and store up (its contents): when the Essence and the Spirit come back and turn around, the old man comes back to the prime of life; squeezing the Dark Door [kidneys] they all flow out below; nourish your Jade Tree [the body] so that it will be strong. (tr. Maspero 1981: 524-526)

The circulation of the qi Breath is completed by that of the jing Essence. While the basic meaning of jing is "sperm in men; menstrual blood in women"; this text uses it to mean "some sort of sublimation dematerialized and capable of blending with the Breath".

"In the middle of the Cinnabar Field, the Essence and the Breath are very subtle." It is in fact necessary to "make the Essence come back", [huanjing]—that is, to make the Essence mingled with the Breath circulate through the body to guide it from the Lower Cinnabar Field to the Upper Cinnabar Field so that it "restores the brain", [bunao]. To be capable of this the Adept must first develop his Essence. The Immortal [Peng Zu] explains in fairly coarse terms how to go about this so as to arouse and agitate the Essence under the influence of the yin Breath, but without expending it, which would be a cause of weakening and would diminish the term of life, for "at all times when the Essence is small, one is sick, and when it is exhausted, one dies." Essence accumulates in the Lower Cinnabar Field; when it is strong enough, it blends with Breath. (Maspero 1981: 345).

There is a parallel between huanjing ("essence returning") and biqi (閉氣, "breath holding"). In Daoist physiology, the spinal cord, was likened to the Yellow River in its "downward-radiating trophic influence", the Huangting Wajing Yujing allusively described huanjing with the phrase Huang He niliu (黃河逆流) "making the Yellow River flow backwards") (Needham and Ling 1956: 150).

The c. 4th century Yufang zhiyao (玉房指要, Essentials of the Jade Chamber) quotes the Han Daoist transcendent Liu Jing (劉京) about sexual intercourse.

The dao of mounting women is first to engage in slow foreplay so as to harmonize your spirits and arouse her desire, to and only after a long time to unite. Penetrate when soft and quickly withdraw when hard, making the intervals between advancing and withdrawing relaxed and slow. Furthermore. do not throw yourself into it as from a great height, for this overturns the Five Viscera and injures the collateral meridians, leading to a hundred ailments. But if one can have intercourse without ejaculating and engage several tens of times in one day and night without losing jing, all illnesses will be greatly improved and one's lifespan will daily increase. Even greater benefits are reaped by frequently changing female partners. To change partners more than ten times in one night is especially good. (Wile 1992: 101)

Maspero says this "elementary exercise" is sufficient for an adept who only wants to prolong life, but "making the Essence return to restore the brain" is necessary if one wants to achieve spiritual transcendence (1981: 522). The ensuing passage quotes an anonymous Xianjing (仙經, Scripture on Transcendence/Immortality") that gives details of how to practice huanjing bunao, where the diverted "jing" seems to be ordinary semen and not supernatrural "jingqi" (精氣, "sexual energy; vitality") (Wile 1992: 48).

The classics on immortality say that the dao of "returning the jing to nourish the brain" is to wait during intercourse until the jing is greatly aroused and on the point of emission. and then, using the two middle fingers of the left hand, press just between the scrotum and anus. Press down with considerable force and expel a long breath while gnashing the teeth several tens of times, but without holding the breath. Then allow yourself to ejaculate. The jing, however, will not be able to issue forth and instead will travel from the "jade stalk" [yujing 玉莖, "penis"] upward and enter the brain. This method has been transmitted among the immortals who are sworn to secrecy by blood pact. They dared not communicate it carelessly for fear of bringing misfortune on themselves. (Wile 1992: 101)

Citing this early description of the urethral pressure method, Pfister says a few people consider it "a beginner’s practice, which should, after some training, be replaced by the free-handed procedure" (2022: 344).

Needham and Lu reason that huanjing bunao "making the semen return to nourish the brain" originated at some very early time during the Zhou dynasty (1046 BCE – 256 BCE), when the discovery was made that if pressure was applied at "the right point in the perineal region the urethra could be occluded, so that at the moment of orgasm the semen instead of being ejaculated could be made to pass into the body." The fact that it passed into the bladder and was later urinated always escaped the notice of the Daoists, and "over more than two thousand years a great structure of theory grew up" concerning how the precious secretion of jing essence was conveyed up into the head and ultimately to the center of the body for the preparation of the internal elixir (1983: 197–198).

Next, the Yufang zhiyao describes how to zhi (止, "stop; suppress; still") ejaculating jing, without mention of "returning" it to the brain or "absorbing" it from the partner.

If one desires to derive benefit from mounting women, but finds that the jing is overly aroused, then quickly lift the head, open the eyes wide and gaze to the left and right, up and down. Contract the lower parts, hold the breath and the jing will naturally be stilled. Do not carelessly transmit this to others. Those who succeed in shedding their jing but twice a month, or twenty-four times in one year, will all gain long life, and at 100 or 200 years will be full of color and without illness. (Wile 1992: 101)

The pre-Sui c. 4th century Yufang mijue (玉房秘訣, Secrets of the Jade Chamber) expands the semantic range of the huanjing bunao ("return the sperm/essence to nourish the brain") vocabulary. This text uses "jing" and "qi" more or less interchangeably, the "woman's sexual energy" in one instance being called yinjing (陰精) and in another similar context yinqi (陰氣). Elsewhere, yinjing (陰精) refers to both" male and female sexual essences" (Wile 1992: 48). In the following examples of Yufang mijue passages, instead of huanjing "returning the jing" to the brain, the text mentions "return the jing and restore the fluid [ye 液]", "mounting the 'vast spring and returning the jing", and "return the jingqi [精氣, "essence and breath"]". Another comparable illustration of semantic polysemy is the word jingye (精液, lit. "seminal/essential fluid"), which Wile translates as "semen", "jing secretions", and "fluids".

First, huanjing "return the jing" is paired with fuye (複液, "restore the fluid") and jingye is translated as "semen".

The dao of yin and yang; is to treasure the semen [精液為珍]. If one can cherish it, one's life may be preserved. Whenever you ejaculate you must absorb the woman's qi to supplement your own. The process of "reestablishment by nine" means practicing the inner breath nine times [內息九也]. "Pressing the one" refers to applying pressure with the left hand beneath the private parts [以左手煞陰下] to return the jing and restore the fluid [還精複液也]. "Absorbing the woman's qi is accomplished by "nine shallow and one deep" strokes. Position your mouth opposite the enemy's mouth and exhale through the mouth. Now inhale, subtly drawing in the two primary vitalities, swallow them and direct the qi with the mind down to the abdomen, thereby giving strength to the penis [陰]. (Wile 1992: 104)

Second, huanjing "returning the jing" occurs after absorbing the woman's jingye (精液, "jing secretions") and mounting the hongquan (鴻泉, the "vast spring"), which may mean "female genitalia" (Wile 1992: 251).

Those who seek to practice the dao of uniting yin and yang for the purpose of gaining qi and cultivating life must not limit themselves to just one woman. You should get three or nine or eleven; the more the better. Absorb her jing secretions [採取其精液] by mounting the "vast spring" and "returning the jing [上鴻泉還精]" Your skin will become glossy, your body light. your eyes bright, and your qi so strong that you will be able to overcome all your enemies. Old men will feel like twenty and young men will feel their strength increased a hundredfold. (Wile 1992: 102)

Third, the Yufang mijue expands the standard huanjing "return the jing" to huanjingqi with qi (氣, "qi; breath"). This context claims the health benefits of avoiding ejaculation include achieving clear vision, preventing deafness, and regulating the Five Viscera.

The dao for achieving clear vision is to wait for the impulse to ejaculate and then raise the head, hold the breath, and expel the air with a loud sound, gazing to the left and right. Contract the abdomen and return the jingqi so that it enters the hundred vessels [縮腹還精氣,令人百脈中也]. (Wile 1992: 104)

Mai (脈, "pulse; artery; vein") in this baimai (百脈, "hundred vessels") occurs in another Yufang mijue passage where jingye is simply translated as "fluids".

If a woman knows the way of cultivating her yin and causing the two qi to unite harmoniously, then it may be transformed into a male child. If she is not having intercourse for the sake of offspring, she can divert the fluids to flow back into the hundred vessels [轉成精液流入百脈]. By using yang to nourish yin, the hundred ailments disappear, one's color becomes radiant and the flesh fine. One can enjoy long life and be forever like a youth. (Wile 1992: 103)

The pre-Tang c. 5th century Dong Xuanzi (洞玄子, Master of the Cavern of Mystery), named after the Dongxuan (洞玄, "Mystery Grotto"), which is one of the Three Grottoes in the Daozang Daoist canon. One passage lists a number of standard techniques for ejaculation control, mentioning neither squeezing the penis base nor pressing the perineum, and concludes, "the jing will rise of itself."

Whenever one desires to ejaculate, one must await the woman's orgasm and then bestow the jing, ejaculating at the same time. The man should withdraw to a shallow depth and play between the "zither strings" [琴絃] and "wheat teeth [麥齒]." The "yang sword tip" [陽鋒] moves deep and shallow like an infant sucking the breast. Then one closes the eyes and turns one's thoughts inward. As the tongue is pressed against the lower palate, arch the back, stretch out the head, dilate the nostrils, hunch the shoulders, close the mouth and inhale, and the jing will rise of itself [精便自上]. The degree of control is always dependent on the individual. One should only ejaculate two or three times in ten. (Wile 1992: 111-112)

Chinese sex manuals variously list terms for vaginal depths, beginning with the shallowest qinxian (琴絃, "zither strings; Labia minora") and maichi (麥齒, "wheat teeth"), between which is the optimum depth for ejaculation (Wile 1992: 236, 243, 255).

The c. 5th century Qingling zhenren Peijun zhuan (清靈真人裴君傳, Biography of Lord Pei, the Realized Person of Pure Refinement)

(The couple) should be free from the effects of wine or repletion of food, and they should be clean of body, for otherwise illness and disease will afflict them. First by means of meditation they must have put away all worldly thoughts, then only may men and women practise the Tao of life eternal. This procedure is absolutely secret, and may be transmitted only to sages; for in it men and women together lay hold of the qi of life, cherishing and nourishing respectively the seminal essence and the blood. It is not a heterodox thing. In it the Yin is gathered up in order to benefit the Yang. If one practises it according to the rules, the qi and the fluids will circulate like clouds, the pure wine of the jing will coagulate harmoniously, and whether one is old or young one will revert to the state of youth. [… After completing some prayers, the man and woman begin coition] The man guards (controls) his reins (i.e., his libido), keeping firm grasp of his semen and refining its qi, (till eventually) they ascend along the spinal column to the brain going against the (normal) current. This is called 'regenerating the primary (vitalities; huanyuan 還元)'. The woman guards (controls) her heart (i.e., her emotions) and 'nourishes her shen,' not allowing the refined fire to move (煉火不動, lian huo butong, i.e., refraining from orgasm), but making the qi of her two breasts descend into her reins, and then also rise up from there (along the spinal column) to reach the brain. This is called 'transforming (life) into the primary (vitalities; huazhen 化真)'. (Needham and Lu 1983: 205-206).

Sui to Tang dynasties

In Sui (561-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasty sex manuals, the "return," "circulation," or "rising" of the jing takes place "naturally as a result of simultaneous stimulation and reservatus; and that male and female sexual energy usually are treated in separate passages in the texts and never explicitly linked" (Wile 1992: 48).

The Tang Fangzhong buyi (房中補益, Health Benefits of the Bedchamber) was preserved in Sun Simiao's 652 classic medical reference Qianjin yaofang (Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand) (chapter 83). This text includes the ejaculation control techniques found in earlier sources, but also adds several new elements. First, it introduces the discovery that "frequent sex with occasional ejaculation is less depleting than occasional sex with habitual ejaculation", which supports the theory that frequent coitus reservatus intensifies sexual power. Second, it presents meditative visualizations and yogic postures for precoital preparation and postcoital absorption, for instance, "Imagine a red color within the navel the size of a hen's egg" for deep penetration without arousing the jing. Third, the text emphasizes the importance of absorbing qi from "above", meaning the woman's breath (Wile 1992: 48).

When one feels the impulse to ejaculate, close the mouth and open the eyes wide, hold the breath and clench the fists. Move the hands to the left and right, up and down. Contract the nose and take in qi. Also constrict the anus, suck in the abdomen, and lie on the back. Now quickly press the pingyi point with the two middle fingers of the left hand. Exhale a long breath and at the same time gnash the teeth a thousand times. In this way the jing will ascend to nourish the brain [則精上補腦], causing one to gain longevity. (Wile 1992: 116)

Pingyi (屏翳, "screen shade") is an alternate name for the Conception vessel CV-1 Huiyin (會陰, Yin Meeting) acupoint at the perineum (Wile1992: 263).

The c. 785 Wangwu Zhenren Liu Shou yi zhenren koujue (王屋真人劉守依真人口訣, Confidential Oral Instructions of the Adept of Mount Wangwu, Presented to the Court by Liu Shou), which is contained in the c. 1029 Yunji Qiqian Daoist Canon, refers to huanjing in several passages.

The Yang enchymoma [dan 丹, Needham's neologism for "elixir within; inner elixir"] can make one ascend (into the heavens); the Yin enchymoma can confer longevity. The Yang enchymoma is a 'returning' (i.e., regenerative) medicine, the Yin enchymoma is the (regenerative) technique of making the jing return [還精之術也]. (Needham and Lu 1983: 204)

There is an analogy between party etiquette and having sex.

One should not dare to be the host, but rather play the part of the guest. We can borrow from the Taoist manuals in speaking of these affairs. He who first lifts up the cup (at a party) is the host, he who responds is the guest. The host first pours out benefits for others, but the guests are those who receive. If one gives like this one's jing is dispersed and one's emotions are exhausted. But if one receives, one's jing is strengthened and one's emotions concentrated. This is because the absorption of the qi of union assists one's own (primary) Yang—in that case what is there to worry about?

The text then goes on to explain the chenghu (垂壺, "riding the wine-pot") technique of "applying the perineal pressure in coitus thesauratus with the heel rather than the hand", and quotes an old Daoist saying that: "Who wishes life unending to attain, Must raise the essence to restore the brain [運精補腦]."

The jing being elevated against the current, both the man and the woman can become immortals and obtain the Tao. … Thus all the old Taoist traditions say that if (the semen is) ejaculated it leads to other men, that is to say, a child is born, but if it is retained it leads to the man himself, that is to say, an (immortal) body is born—that is the meaning of it. (Needham and Lu 1983: 208-209; cf. 159)

Concurrent with historical developments of Daoism, the huanjing bunao technique of "Returning the essence to replenish the brain" evolved from sexual yoga to cosmic meditation. This method originally consisted of controlling the flow of jing (精, "seminal essence"), and was related to fangzhongshu (lit. "bedchamber arts", "lovemaking techniques") and yangsheng ("longevity practices") (Despeux 2008: 514). During the Tang dynasty, Neidan (Inner Alchemy) became popular and huijing benao took on a different meaning that refers to the repeated cycling of the essence in the first stage of the practice, called zhoutian (周天, "celestial circuit; continuously circular movement of the universe") (Despeux 2008: 515).

By the end of the Tang dynasty, many Chinese sex manuals were no longer extant, and only known by titles listed in bibliographies. Fortuitously, the Japanese physician Tamba Yasuyori (丹波康頼, 912–995) compiled and published many fragments of early Chinese medical writings in his 984 Japanese Ishinpō (醫心方, Formulas of the Heart of Medicine), which was partly based on the 7th century Zhubing yuanhou lun (General Treatise on the Etiology and Symptomology of Diseases). Chapter 28 of the Ishinpō, Japanese Bōnai (房内, Art of the Bedchamber) contains several texts, such as the Sunü jing. The Chinese editor Ye Dehui republished them in his 1907 Shuangmei jing’an congshu (雙梅景闇叢書, Shadow of the Double Plum Tree Anthology), which outraged many Chinese readers.

Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties

Sex manuals continued to be published during the Song (960-1279), Yuan (1271–1368), and Ming dynasties (1368–1644).

The c. 1020 Yunü sunyi (御女損益, Dangers and Benefits of Intercourse with Women) is chapter 6 of the Yangxing yanming lu (養性延命錄, "On Nourishing Inner Nature and Extending Life"), attributed to Tao Hongjing or Sun Simiao. It presents some new themes, such as postejaculatory remediation, advising to supplement leaked semen by engaging in daoyin exercise to "circulate energy internally", and an early description of cloudy urine from retrograde ejaculation (Pfister 2022: 345).

To lock the jing [閉精] by repression is a practice difficult to maintain and easy to lose. Furthermore, it causes a man to lose jing through leakage and for his urine to be turbid. It may even lead to the illness of copulation with ghosts. Also, by seeking to prevent the qi from becoming excited, they weaken their yang principle. Those who desire to have intercourse with women should first become aroused and cause [the penis] to rise up strong. Slowly engage her and absorb her yinqi. Circulate the yinqi and after a moment you will become strong. When strong, employ it, being certain to move slowly and in a relaxed manner. When your jing becomes aroused, stop. Lock the jing and slow the breath. Close the eyes. lie on the back and circulate your internal energy. When the body returns to normal, one may have intercourse with another woman. (Wile 1992: 120)

Another passage describes some more serious consequences of losing jing "seminal essence".

Some are shocked into insanity or experience "emaciation-thirst" disease [xiaoke 消渴]. Some lose their minds or suffer malignant sores. This is the result of jing loss. When emission does occur, one should circulate energy internally to supplement the loss in that area. Otherwise, the blood vessels and brain daily will suffer more harm. When wind and dampness attack them they take ill. This is because common people do not understand the necessity of supplementing what is lost in ejaculation. (Wile 1992: 120)

Unlike earlier texts recommending the sexist concept of male release and absorption from females, the Yunü sunyi is the first to describe a path of mutual immortality for both sexes through a combination of deep penetration, low arousal, and dantian visualizations (Wile 1992: 48).

The classics on immortality state that the tao of man and woman achieving immortality together is to use deep penetration without allowing the jing to be aroused. Imagine something red in color and the size of an egg in the middle of the navel. Then slowly move in and out, withdrawing when the jing becomes aroused. By doing this several tens of times in the morning and in the evening, one may increase the lifespan. Man and woman should both calm their minds and maintain their concentration. (Wile 1992: 121)

Lastly, this text misquotes the Daodejing: "If one returns the jing to nourish the brain, one will never grow old [還精補腦,可得不老矣]." (Wile 1992: 126); suggesting that this Laozi (老子) may literally mean an "old one, or wise one" author rather than the Laozi text (1992: 265).

The c. 1029 Yunji Qiqian quotes the Shangjing dongzhen pin (上清洞真品, The Ranks of Spirits and Substances, a Dongzhen Scripture of the Supreme Clarity Heavens), which paraphrases huanjing bunao:

The primary qi (yuanqi) is (the main factor of) life and death; life and death depend on the art of the bedchamber. One must follow the method of the Tao of retention, so that the jing can be changed into something wonderful; one must make this qi flow and circulate incessantly without hindrance or obstruction. As the proverb says: 'Running water doesn't rot, and a door often used is not eaten by woodworms.' Those who understand the mystery within the mystery know that a man and a woman can together restore (their vitality), and both can become immortals; this is truly what may be called a marvel of the Tao. The manuals of the immortals say: 'One Yin and one Yang constitute the Tao; the three primary (vitalities) and the union of the two components; that is the [inner elixir]'. When the flow goes up against the stream to nourish the brain, this is called 'making the jing return' (huanjing) [溯流補腦謂之還精]. (Needham and Lu 1983: 124)

The early 13th-century Xiyue Dou xiansheng xiuzhen zhinan (西嶽竇先生修真指南, Teacher Dou's South-Pointer for the Regeneration of the Primary [Vitalities], from the Western Sacred Mountain) lists the qibao (七寶, "seven precious things")—shen (神), qi (氣), mai (脈, "vessels and nerves"), jing (精), xue (血, "blood"), tuo (唾, "saliva"), and shui (水, "juices of organs")—necessary for the qifan (七返, "seven reversions"). It says, "if the juices are abundant they can generate saliva, if the saliva is abundant it can change into blood, if the blood is abundant it can be transmuted the jing (seminal essence), if the jing is abundant it can (be sent up to) nourish the brain, if the brain is nourished it can strengthen the qi, and if the qi is copious it can complete and perfect the shen." (tr. Needham and Lu 1983: 151).

The Ming c. 1500 Sunü miaolun (素女妙論, Wondrous Discourse of Sunü) presents a new theory with a parabolic curve of sexual vitality, peaking at middle age, which separates the concept of sexual energy from simple ejaculatory potency (Wile 1992: 48).

A boy reaches puberty at sixteen, but his vitality is not yet sufficient and his mind not yet stable. He therefore must observe abstinence. When he reaches the age of twenty, his vitality is becoming stronger, and the jing is concentrated in the intestines and stomach. One may then ejaculate once in thirty days. At thirty, the vitality is strong and abundant, and the jing is in the thighs. One may ejaculate once in five days. At forty, the jing is concentrated in the lower back and one may ejaculate once in seven days. At fifty, the vitality begins to decline, and the jing is concentrated in the spine. One may then ejaculate once in half a month. When one reaches sixty-four years of age, the period of one's potency is finished and the cycle of hexagrams complete. The vitality is weak and the jing secretions exhausted. If one can preserve one's remaining qi after sixty, then those who are vigorous may still ejaculate. When one reaches seventy, one must not let the emotions run wild. (Wile 1992: 131).

The Sunü miaolun explains self-cultivation through absorbing a partner's energy and supplementing oneself:

"Heaven and earth combine prosperously" and yin and yang cooperate generously. First examine her state of emotional excitement and then observe whether the stages of qi arousal have reached their peaks or not. Energetically withdrawing and inserting, one realizes the marvel of "adding charcoal." This secures and strengthens one's own "yang coffers." Enjoying scented kisses and pressing closely together, absorb her yinjing to supplement your yangqi [吸陰精而補陽氣]. Draw in the qi of her nostrils to fortify your spine marrow [脊髓]. Swallow her saliva to nourish your dantian [elixir-field in the lower abdomen]. Cause the hot qi to penetrate the niwan [center of the brain] point and permeate the four limbs. As it overflows, it strengthens the qi and blood, preserves the complexion, and prevents aging. (Wile 1992: 133)

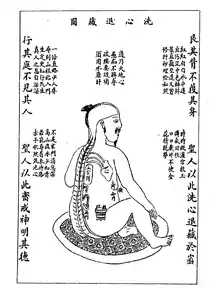

The 1615 Ming dynasty Xingming guizhi compendium of Inner Alchemy pictures an adept practicing huanjing bunao. The "Illustration of Reverse Illumination" shows the vertebral column, which is flanked by the shen (腎, "TCM kidneys")—distinct from the anatomical kidneys—which are respectively labeled as longhuo (龍火, "dragon fire") on the right, a symbol of yang energy within the yin side of the body, and hushui (虎水, "tiger water") on the left, a symbol of yin energy within the yang side of the body (Little 2000: 348–349). This illustration shows twenty-four "vertebra", some labeled with the traditional Chinese medical acupoint names for fourteen of the twenty-eight points of the Dumai (督脈) Governing Vessel. The relevant huanjing bunao acupoints are GV-1 Changqiang (長強, Long and Strong) halfway between the coccyx and the anus, and Conception vessel CV-1 Huiyin (會陰, Yin Meeting) halfway between the scrotum and the anus (Needham and Lu 1983: 231).

Cross-cultural counterparts

Although the Daoist practice of "returning the seminal essence to replenish the brain" may seem to be a uniquely Orientalist mystery, there are historical counterparts in the fields of Ancient Greek medicine and Tantric sex.

In Ancient Greece, some physicians and philosophers believed that semen originated in the brain and moved through the spinal marrow. Plato's c. 360 BCE Timaeus dialog considered the brain and spinal marrow as a special form of bone marrow in which "God implanted his divine seed" (Noble 2014: 399). The marrow supposedly passes down the spine and communicates its "universal seed stuff" to the genitalia for procreative purposes. "And the marrow inasmuch as it is animate and has been granted an outlet from the passage of egress for drink [the penis] has endowed that part with a love for generating by implanting therein a lively desire for emission" (Noble 2014: 400).

Regarding the semen, Hippocrates (c. 460- c. 370 BCE) said, "The greater quantity of the material of generation, it is believed on the authority of Galen, is drawn from the brain." (Opera, De semine). This refers to the Pseudo-Galen Definitiones Medicae, "The semen, as Plato and Diocles opine, is discharged by the brain and the spinal marrow, while Praxagoras and Democritus and thereafter Hippocrates maintain it comes from the whole body." (Noble 2014: 397)

Based upon contemporary medical resources, the anatomical drawing by Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) shows two duct systems entering the penis, one with several branches from the lower spinal cord fusing to form a duct that goes directly through to the tip of the penis, the other system going from the testes with a duct sweeping backwards to circle the bladder before returning to enter the penis (Noble 2014: 393). In the bottom left sketches, note the two channels in the penis, one for urine and one for semen, rather than a single urethra. Leonardo "labeled the spinal cord 'generative power', reflecting the Platonic view (which he later abandoned) that semen derives from the spinal marrow" (Pevsner 2002: 219). Leonardo da Vinci corrected his anatomical mistakes in a lesser-known second (probably after 1508) drawing accurately based on dissection (Noble 2014: 395).

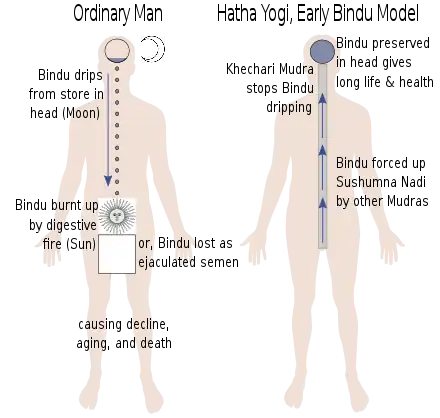

In Ancient India, the Chinese technique of "returning the seminal essence to replenish the brain" has parallels in two associated mudras (lit. "seal; mystery; gesture")—symbolic body postures practiced in hatha yoga and kundalini. Vajroli mudra is practice of a male yogi preserving his semen after ejaculation by drawing it up through his urethra from the vagina of a female yoginī. Khecarī mudrā is a kumbhaka breath retention practice of rolling the tip of the tongue backwards and upwards until it touches the soft palate and reaches towards the nasal cavity [cf. Dong Xuanzi above, Wile 1992: 112]. Khecarī mudrā is said to "accomplish the simultaneous immobilization of breath, thought and semen, obstructing the throat with the tongue in kumbhaka apnea, secreting copious saliva, and never emitting semen" (Needham and Lu 1983: 274).

The circa 100 BCE to 300 CE Dhyanabindu Upanishad describes the khecarī mudrā posture "when the tongue enters the cavern of the cranium, moving contrawise (backward). The eye-glance penetrating between the eyebrows" and how it allows one to accomplish vajroli mudra (Ayyangar 1938: 164).

For him (whose tongue enters) the hole (of the cranium), moving upwards beyond the uvula, whose semen does not waste away, even when he is in the embrace of a beautiful woman, as long as the semen remains firmly held in the body, so long, where is the fear of death for him? As long as the Khe-carī-mudrā is firmly adhered to, so long the semen does not flow out. Even if it should flow and reach the region of the genitals, it goes upwards, being forcibly held up by the power of the Yoni-mudrā (sanctified by the Vajroli). (Ayyangar 1938: 164-165).

The c. 150 CE Yogatattva Upanishad describes both mudras together.

That Yogin who practices Vajrolī, he proves to be the receptacle of all psychic powers. Should he attain (that), Yoga-siddhi is on the palm of his hand. He will know what has transpired and what is yet to take place. Khe-carī will also surely be in his reach. [Vajrolī consists in plunging the glans penis in a leaden cup of cow's milk, drawing up the milk and dropping it and repeatedly practising it: then dropping the semen in the genital organ of the female and drawing it up with the Śoņita ["blood; female vital energy"] discharged by her.] (Ayyangar 1938: 321).

And with the vajroli-mudra,

the yogin should ejaculate, but after having done so he should positively regain this medhra (the bindu or semen emitted), and "having done so by a pumping process, the yogin must conserve it, for by the loss of the bindu comes death, and by its retention, life." Thus we seem here to be in the presence of a veritable seminal aspiration, the muscles of the abdomen creating a partial vacuum in the bladder and so permitting the absorption of part at least of the vaginal contents (Needham and Lu 1983: 274)

The Yogatattva Upanishad also records a marvelous side-effect of practicing semen retention, "Avoiding intercourse with women, he should earnestly betake himself to the practice of Yoga. On account of the retention of semen there will be generated an agreeable smell in the body of the Yogin." (Ayyangar 1938: 311).

It is likely that the method of perineal pressure to avoid ejaculation was also used in India. For instance, the c. 320-390 CE Mahayana-sutra-alamkara-karika uses the term maithunasya parāvṛttau ("returning the semen: rerouting the semen"), which is closely analogous to Chinese huanjing (Needham and Lu 1983: 275).

The Dutch diplomat and author Robert van Gulik proposed a historical thesis that sexual mysticism or sexual yoga originated in China, rather than India as commonly assumed (1971: 339-359). The 1973 discovery of the 2nd-century BCE Mawangdui medical manuscripts (above) strengthened the probability that Daoist sexual practices, including huanjing bunao, were the precursor of Tantric sexual practices (Wile 1992: 157). Van Gulik gives Buddhist and Hindu examples of spiritual semen retention.

Some specialized Sanskrit and Pali terminology is used in the following descriptions of Hindu and Buddhist adepts visualizing semen moving up the spinal cord into the brain. Within the human body, prana ("life force, vital principle") energies are thought to flow through nadi ("tubes, channels, nerves") that connect the chakra ("wheel") energy centers. There are three main nadi channels. The most important central sushumna goes along the spinal cord and connects the muladhara ("base chakra") to the sahasrara ("thousand-petalled" "crown chakra"). The left channel ida or lalana is associated with female, ova, moon, etc.; and the right channel pingala or rasana is associated with male, semen, sun, etc.

First, esoteric Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism introduced "a highly specialized sexual mysticism, based on the principle that complete unity with the deity and supreme bliss could be achieved by a meditative process based on the coitus reservatus" (van Gulik 1971: 341). According to Giuseppe Tucci, "the disciple, through the sexual act, reproduces the creative moment. But the act must not be performed down to its natural consequences; it should be controlled by pranayama [Yogic breath-control], in such a manner that the semen goes its way backwards, not flowing downwards but ascending upwards, until it reaches the top of the head, hence to vanish into the uncreated source of the Whole" (Tucci 1949: 242). In order to overcome the sexual dualism of the lalana and rasana nadi channels, a male Vajrayana practitioner meditates on the bodhicitta ("enlightenment-mind; thought of awakening") while having intercourse with a female partner, acquiring her female energy stimulates his bodhicitta, which blends with his activated but unejaculated semen into a new, powerful essence called bindu ("drop; dot") or "translated semen" (tr. van Gulik). The bindu breaks through the separation of lalana and rasana, and opens up a new, asexual energy channel known as avadhutika ("the cleansed one"). The bindu rises up this channel, through the chakras and reaches the crown chakra, whereupon the practitioner can purportedly achieve nirvana (van Gulik 1971: 342). Although Vajrayana incorporated older Buddhist and Hindu thought, the "conception of the coitus reservatus supplying a shortcut to complete enlightenment was an entirely new element, in that form unknown in pre-Vajrayana Buddhism" (van Gulik 1971: 343).

Second, Saikva and Sakta Tantra schools of Hindu Shaivism also practiced sexual mysticism. The process of merging the separate pingala and lalana channels, under the stimulus of real or visualized coitus reservatus with a female partner, is called Kundalini yoga. The dormant female energy in the yogi's body is called technically kundalini ("coiled snake"), which after arousal creates a new, asexual nerve channel called sushumna, along which the adept's unejaculated "translated semen" ascends until it reaches the brain. There the final union with the deity is visualized as the embrace of the god Shiva and goddess Parvati (van Gulik 1971: 343-344). In Shaktism, a practitioner who has mastered the spiritual coitus reservatus technique is called urdhvaretas ("one who can make semen flow upward [in the body]"), a practice of Brahmacarya ("celibacy"). According to Hindu concepts, a subtle form of semen exists throughout the entire body, and can be transformed into a gross form in the sexual organs (van Gulik 1971: 345). "To be urdhvaretas is not merely to prevent the emission of gross semen already formed but to prevent its formation as gross seed, and its absorption in the general system" (Woodroffe 1919: 199). Along with Chinese Daoists, the Sakta adept considered the semen his most precious possession. The 15th century Hatha Yoga Pradipika says: "He who knows Yoga should preserve his semen. For the expenditure of the latter tends to death, but there is life for him who preserves it" (Woodroffe 1919: 189). Van Gulik concludes that, "Since sexual mysticism based on the coitus reservatus flourished in China since the beginning of our era, whereas it was unknown in India, it seems obvious that this particular feature of the Vajrayana was imported into India from China, probably via Assam" (1971: 351).

Finally, Joseph Needham says a sexual ritual of the Hindu Vaishnava Sahajiya tradition has an equivalence to Chinese huanjing bunao ("making the jing, or seminal essence, return") that is "too close to be accidental" (1956: 428). This method of maithuna ("Tantric sexual intercourse") involves the sushumna central nadi channel. A man and woman follow a series of postures and recitations that should result in "the passing of seminal fluid through the middle nerve, which will then go upwards towards the region of paramātmā ["supreme self"]. If it passes through the other two nerves, the result will be either the procreation of children, or mere waste of energy. It is only the middle nerve which is the source of perpetual enjoyment." (Bose 1930: 71).

See also

- Edging (sexual practice), maintaining long-lasting sexual arousal without reaching climax

- Erotic sexual denial, the practice of refraining from sexual experiences in order to increase erotic arousal

- Karezza, a term for coitus reservatus coined by Alice Bunker Stockham

- Maithuna, sexual intercourse within Tantric sex, or alternatively to the specific lack of sexual fluids generated

- Sarvangasana, a yogic supported shoulder stand believed to reverse the downflow loss of (bindu) life-force

- Shirshasana, a yogic headstand believed to reverse the downflow loss of bindu life-force

- Viparita Karani, a yogic shoulder stand believed to reverse the downflow loss of bindu life-force

References

- Ayyangar, TR Srinivasa (1938), The Yoga Upanishads, The Adyar Library.

- Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen (2004), "Zhenxian bizhuan huohou fa 真仙祕傳火候法", in Schipper 2004: 807–808.

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R. (1997), Early Daoist Scriptures, with a contribution by Peter Nickerson, University of California Press.

- Bose, Manindra Mohan (1930), The Post-caitanya Sahajia Cult Of Bengal, University of Calcutta.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2002), To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents, University of California Press.

- Despeux, Catherine (2008), "Huanjing bunao 還精補腦 "returning the essence to replenish the brain"," in The Encyclopedia of Taoism, ed. Fabrizio Pregadio, Routledge, 514–515.

- van Gulik, Robert Hans (1951), Erotic Colour Prints of the Ming Period, privately printed.

- van Gulik, Robert Hans (1961), Sexual Life in Ancient China; a Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from ca. 1500 B.C. till 1644 A.D., Brill.

- Harper, Donald (1987), "The Sexual Arts of Ancient China as Described in a Manuscript of The Second Century B.C.", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 47.2: 539-593.

- Harper, Donald (1998), Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts, Kegan Paul. [Note that the page references are to the PDF digital edition.]

- Judy, Ron S. (2015), "The Semen in the Subject: Deferral of Enjoyment and the Postmodernist Taoist Ars Erotica", The Comparatist 39: 135-152.

- Kroll, Paul W. (2017), A Student's Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese (rev. ed.), E.J. Brill.

- Little, Stephen (2000), Taoism and the Arts of China, with Shawn Eichman, Art Institute of Chicago.

- Maspero, Henri (1981), Taoism and Chinese Religion, tr. by Frank A. Kierman, University of Massachusetts Press.

- Needham, Joseph and Wang Ling (1956), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought, Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-Djen (1983), Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. V: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 5: Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Physiological Alchemy, Cambridge University Press.

- Noble, Denis, Dario DiFrancesco, and Diego Zancani (2014), "Leonardo Da Vinci and the Origin of Semen", Notes & Records, The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 68: 391–402.

- Pevsner, Johnathan (2002), "Leonardo da Vinci’s Contributions to Neuroscience", Trends in Neurosciences 25: 217–220.

- Pfister, Rodo (2022), "The sexual body techniques of early and medieval China – underlying emic theories and basic methods of a non-reproductive sexual scenario for non-same-sex partners", in Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine, ed. by Vivienne Lo and Michael Stanley-Baker, 337-355.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2022), "Time in Chinese alchemy", in Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine, ed. by Vivienne Lo and Michael Stanley-Baker, 427-443.

- Rocha, L. A. (2022), "The question of sex and modernity in China, part 1: from xing to sexual cultivation", in Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine, ed. by Vivienne Lo and Michael Stanley-Baker, 381-388.

- Ruan, Fang Fu (1991), Sex in China: Studies in Sexology in Chinese Culture, Springer.

- Schipper, Kristofer M. (1993), The Taoist Body, tr. Karen C. Duval, University of California Press.

- Schipper, Kristofer and Franciscus Verellen (2004), The Taoist canon: a historical companion to the Daozang, Vol. 2 The Modern Period, University of Chicago Press.

- Tucci, Giuseppe (1949), Tibetan Painted Scrolls, vol. 1, La Libreria dello Stato.

- Umekawa, Sumiyo and David Dear (2018), "The Relationship between Chinese Erotic Art and the Art of the Bedchamber: A Preliminary Survey", in Imagining Chinese Medicine, ed. by Vivienne Lo et al., Brill, 215-226.

- Wang Yishan (2022), "Sexing the Chinese medical body: pre-modern Chinese medicine through the lens of gender", in Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine, ed. by Vivienne Lo and Michael Stanley-Baker, 356-367.

- Wile, Douglas (1992), Art of the Bedchamber: The Chinese Sexual Yoga Classics, Including Women's Solo Meditation Texts, State University of New York.

- Woodroffe, John (1919), The serpent power: being the Ṣaṭ-cakra-nirūpana and Pādukā-pañcaka: two works on Laya-yoga, reprint Dover Publications (1974).